“At this point in my research, I was wishing that I could write something about my beloved home state’s history—anything—and not have it come around to race and white supremacy…. So much for telling an innocent little story about a family of bird egg collectors and the popular passion for oology in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.”

When I got home from Chicago, I did a little research on the other bird egg collectors in Richard Smithwick’s family. His older brother, John Washington Pearce Smithwick, of course, stood out.

J. W. P. Smithwick was born in Merry Hill, in Bertie County, N.C., in 1870, the son of a Confederate veteran who still had a bullet hole in his chest.

A precocious young man, he had begun collecting bird eggs seriously by 1888. He was publishing a little ornithological journal called The Hummingbird by 1890, and in 1897 he wrote a book called Ornithology of North Carolina: A List of the Birds of North Carolina, With Notes of Each Species.

Published by the N.C. Agricultural Experiment Station in Raleigh, the book was an authoritative text at that time.

He donated his bird egg collection, said to be the state’s largest, to the State Museum (now the N.C. Museum of Natural Sciences) in Raleigh in 1898.

After giving up his eggs, Smithwick focused on medicine. After studying at UNC and attending medical school at the University of Maryland, he had earned his medical license in 1894.

A few years later, he and his wife moved first to Aurora, a village in Beaufort County, N.C., that was her home. After a brief time there, they picked up and moved again, this time to La Grange, a small town in Lenoir County, where he opened a medical practice.

My research showed that Dr. Smithwick had a busy life in La Grange. In addition to his medical practice, he taught science classes at La Grange High School. He was active in the Methodist church, the Masonic lodge and the Democratic Party. He was eventually elected the town’s mayor.

J. W. P. Smithwick’s intellectual interests were also far ranging. He won an award from a New York medical journal for an article on the treatment of malaria. He edited the Southern Medical Journal. He even took time to write the occasional poem and short story, as well as to patent an invention or two.

He was, in short, the old-fashioned kind of country and small town doctor that I encounter surprisingly often when I am doing research on eastern N.C. in the latter part of the 19th and early 20th century.

They were often men that excelled in medical school, but still chose to come home to eastern N.C. to practice their trade and make a contribution. They frequently proved as adept at birthing babies in a tenant farmer’s cabin in the middle of a winter night as saving a breech-born calf, and quite a few of them could quote the Bible, the Latin poets and the latest scientific journals with equal vigor.

I also discovered a very dark side to young Dr. Smithwick. I was looking at historical newspapers, when I came upon an article that he published in a Raleigh paper called The Farmer and Mechanic. The subject was the farthest thing imaginable from the study of birds and bird eggs, or what I thought might be the concerns of a small town doctor.

I cringed when I read the headline: “Ultimate Solution to the Negro Problem Suggested.”

I felt an all-too-familiar knot in the pit of my stomach. Let’s face it: no article with a headline that contains the phrases “Negro Problem” and “Ultimate Solution” can be good.

As I got ready to read Smithwick’s words, I didn’t know exactly what was coming, but the date of the article was November 10, 1903— only 5 years after the wave of white racial violence and political skullduggery that led to the disfranchisement of the state’s blacks and laid the groundwork for the social order that we call “Jim Crow.”

It was, in fact, 5 years to the day after the state’s worst incident of white political violence against African Americans– the one that is often called the Wilmington race riot of 1898.

In that article, the young physician began by placing blacks at the bottom of an evolutionary ladder, while he placed northern European whites at its pinnacle. This was the same kind of Social Darwinism that, in my essay a couple weeks ago on Edward Price Bell’s notebooks at the Newberry Library, white supremacists in Wilmington used to justify the violent overthrow of the city’s government and the deadly assault on the black community.

Smithwick was quite explicit in that regard. “The negro…,” he wrote, “seems to be living over the instincts and habits of his animal sub-human ancestors.” He went on to accuse the state’s black citizens of being prisoners of bestial urges, inferior intelligence and “primitive instinct.”

At this point in my research, I was wishing that I could write something about my beloved home state’s history—anything—and not have it come around to race and white supremacy.

Above all, Smithwick was obsessed with the thought of black men raping white women. It had nothing to do with reality, but a great deal to do with white people and the history of race in America.

That, too, harkened to Wilmington and the white supremacy campaign of 1898. For their political gain, the state’s Democrats manufactured a fear of black rapists to weaken a governing political alliance between blacks and whites.

Raised from smoldering embers to a flame, those fears incited the killing of black men and the political overthrow of blacks and their white allies.

Smithwick added a scientific claim to his proposal. He argued that black men had a biological trait, like a gene, that led them to pursue white women. “A perversion from which most races are exempt, prompts the negro’s inclination toward the white woman, while other races incline toward the females of their own,” he wrote.

If you’re starting to feel sick, believe me, I understand. The young doctor’s words were of course poppycock, but one can scarcely overestimate how deeply white beliefs of that kind shaped North Carolina politics and society in the early 20th century.

Smithwick was, at best, only marginally worse than a lot of other white leaders and thinkers. In 1903, after all, North Carolina had a governor that was an ardent, self-proclaimed white supremacist and his political party—the Democrats— proudly called itself the “party of white supremacy.”

The threat of white violence against blacks lay heavy in the air in those days. There was, in fact, plenty of violence.

But sometimes, in the historical record, you get a glimpse of even worse possibilities. At a rally in Goldsboro, N.C., in 1898, for instance, the mayor of Durham warned the state’s black citizens, “Resist our march of progress and civilization and we will wipe you off the face of the earth!”

“The Anglo-Saxon planted civilization on this continent and wherever this race has been in conflict with another race, it has asserted its supremacy and either conquered or exterminated its foe,” he told the crowd.

“This great race has carried the Bible in one hand and the sword [in the other],” he added.

The crowd was estimated at 8,000 people, and he shared the stage with a future governor and U.S. senator, who presumably applauded his words.

I am reminded yet again how, when you study history, the veneer of civilized society can seem very thin and very frail.

I read on. In search of a remedy “to tame the bestial impulse,” J. W. P. Smithwick dismissed anything but radical approaches. He did not believe, for instance, that religion or schooling could dampen black men’s alleged interest in white women sufficiently.

Instead, he proposed a course of action that would not have seemed out of place in Nazi Germany: a surgical response.

“It may be needful to call upon surgical aide for elimination,” he argued. He was proposing castration, or at the very least some kind of surgical sterilization.

To him it seemed a no-brainer. He wrote, “The honor of one Caucasian woman secured against the assaults of a sexual beast belonging to an alien race must awaken suggestions from the great medical heart of America which will echo from ocean to ocean.”

That was his scientific “solution” to the “negro problem”: define black men as part of an alien race and treat them in the way you might a dog or a horse.

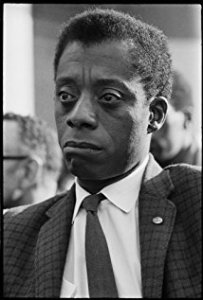

James Baldwin, novelist, essayist and one of the most compelling intellectual voices of the 20th century. If you haven’t seen it yet, I strongly recommend Raoul Peck’s recent documentary, “I Am Not Your Negro.” It’s a brilliant introduction to Baldwin and his thinking on race in the U.S.

In the 1960s, as whites bombed churches and schools across the South, and took fire hoses and billy clubs to child protestors, the African American writer James Baldwin worried that racism was turning white people into “moral monsters.” He feared that he was witnessing “a death of the heart.”

Baldwin wasn’t being glib. He was a great writer, but he was also a deeply compassionate man. He did not hate white people, and he was sincerely worried.

I often think about his words when I see people in the historical record talk like our young medical doctor in La Grange.

I think about his words when I hear people talk that way today, too.

Smithwick was not even recommending a penalty for a crime. His “solution” was worse: he was proposing that surgeons castrate any black man who, in his words, “comes within the range of suspicion.”

He didn’t mean suspicion of having committed a sexual crime. Let’s face it: a black man suspected of rape or attempted rape in 1903 was unlikely to have made it to the operating room.

Instead, Smithwick was proposing surgical castration for black men suspected to have a propensity toward romantic or sexual interest in white women.

He did not clarify how white authorities would determine a black man’s sexual interest in white women, but we have to remember that whites lynched black men in the South for as little as flirting with a white woman.

I once wrote about a lynching in Martin County, N.C., that was done in retaliation for a young black man allegedly asking a white woman on a date—and that was half a century later in 1957.

Dr. Smithwick only insisted that the decision to castrate a black man rest in the hands of medical doctors. It should be, he wrote, “the duty of the physician, and a committee, with legal authority.”

I thought immediately of North Carolina’s “eugenics board” that ordered the forced sterilization of thousands from the 1920s to the 1970s.

Of course I also thought of other times in history when physicians had been part of an “ultimate solution.”

So much for telling an innocent little story about a family of bird egg collectors and the popular passion for oology in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

When I was at the Field Museum of Natural History (described in my last post), I looked long and hard at J. W. P. Smithwick’s egg sets. Most belonged to his brother, Richard, but some of his were there, too.

I thought about the gentleness that it took to retrieve those eggs. They looked so thin and fragile in the collection cases. He must have had a supremely delicate touch to make the tiny hole in each of them and remove the insides, and to separate out the little twigs and individual threads of moss and spider web in order to describe the nests.

I thought, too, about the delicacy of outlook that bird egg collecting entailed. Why choose wild bird eggs, after all, when he could have collected coins or fossils or arrowheads or a thousand other things?

J. W. P. Smithwick chose bird eggs. To me that suggests a certain sensitivity to the weak and vulnerable things in life. But maybe I don’t understand at all. Here I am, already growing old, and sometimes I feel as if I still don’t understand so many things.

This is heartbreaking. It flies in the face of the history of so many people like me, who identify as Black, but actually are of biracial ancestry. It’s hard not to wonder if the men who promoted these ideas of Black men pursuing white women were not actually projecting their own desires about Black women. I think of my white maternal 3 times great-grandfather who fathered the 5 children of a woman enslaved by his mother-in-law. That happened in upstate SC in the 1830’s and 1840’s. Later I was afraid to read letters in the Wilson Library collection that my white paternal great-grandfather wrote in 1898 when he taught at Wake Forest. The letters expressed progressive views about race, but he fathered the oldest son of a Black woman in the early 20th century. White supremacy has tainted so much of American life. We must face our shared history, unpleasant as it often is. Beverly

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yikes. The white supremacy plague was indeed an epidemic. Maybe still is. Keep up the fine work David.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So many horrible things in our history. I thought that people not saying racist things in my presence meant they were evolving, only to find out that a lot of them had just learned better than to say awful things in front of me because they would get an unpleasant result. In the company of others, they still harbored their prejudices.

LikeLiked by 1 person

David what a powerful essay and such a horribly chilling story,. I appreciate your sharimg it, to help us continue to make the history of tpday better for the future.

Love, laneir

On Sat, Nov 18, 2017 at 10:23 AM, David Cecelski wrote:

> David Cecelski posted: “”At this point in my research, I was wishing that > I could write something about my beloved home state’s history—anything—and > not have it come around to race and white supremacy…. So much for > telling an innocent little story about a family of bird egg c” >

LikeLike