In the late winter or early spring of 1938, a photographer named Charles Farrell visited Colington, an old fishing village on North Carolina’s Outer Banks. Today condominiums and resorts surround Colington, but at that time Farrell discovered only a quiet, out-of-the-way settlement with perhaps 200 or 300 residents divided between two small islands, Little Colington and Big Colington.

Among the more secluded parts of the Outer Banks, the islands rested between broad, marshy bays to the north and south. The waters of the Albemarle Sound, one of the country’s largest estuaries, shaped the community’s western edge, while Bodie Island, another of the northern Outer Banks, lay a stone’s throw to the east.

The village’s homes, as well as a one-room schoolhouse, a Methodist church and two stores, stood among high dunes that were heavily wooded and fringed by salt marsh. The commercial center of the village was Levin and Sadie Stetson’s general store, which also served as the community’s post office.

This is part of a series that I’ve been doing on Charles A. Farrell’s photographs of fishing communities on the North Carolina coast in the 1930s. In recent years, I’ve been taking his photographs back to the coastal communities where he took them and searching for the stories behind them.

When Farrell visited, Works Progress Administration (WPA) laborers had just built the first bridge and paved road to the island, making Colington more accessible to the outside world than ever before.

Farrell’s photographs at Colington were unusual for him. On other parts of the North Carolina coast, he turned his camera mainly on fishermen’s and women’s work lives– fishing, processing fish, boatbuilding and net making.

Not in Colington: on those shores, he left us a memorable portrait of a fishing family and their home life during the Great Depression.

-1-

All photographs are from the Charles A. Farrell Papers at the State Archives of North Carolina, unless otherwise noted.

A fisherman’s home, Little Colington Island. In an endearing moment of intimacy, Felix Beasley and his wife Lizzie laugh and tell stories at the dinner table. Lizzie’s children, Callie and Ivey, eat their supper behind the couple. Their house, an old houseboat that washed ashore in a storm, sits on land next to the canal that separates Little Colington Island from Bodie Island.

Born and raised in Nags Head Woods, on Bodie Island, Lizzie was known for her light step and the twinkle in her eye. According to her descendants, she had scarlet fever when she was a young woman, perhaps 15 or 16 years old, and the fevers left her with a rather child-like demeanor for the rest of her life.

The difference in Lizzie and Felix’s ages, spanning nearly four decades, is striking. The couple, on the other hand, seems more than a little happy.

One of Felix Beasley’s grandsons, Miles Midgette, of Roanoke Island, told me that he recognized a family trait in these scenes. The Beasleys, he said, have always been “happy, joyful people.”

-2-

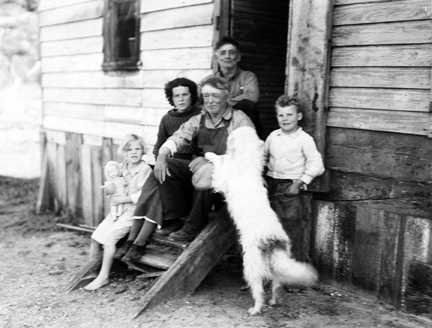

The Beasley family, along with Lizzie’s father Louis Littleton “Lit” Johnson and an enthusiastic canine friend on the stoop of the Houseboat (as locals always called the home). Felix’s younger brother, Morris, also a fisherman, lived with the family as well, but is not in this photograph.

A pair of long-handled dip nets rests on the ground on the left. Felix was in declining health, but still made a little money by crabbing and eeling. To catch blue crabs, he set trotlines, a once common way to harvest blue crabs that in later years gave way to crab pots.

Trotlining involved anchoring a heavy rope on both ends in a quiet bay or salt marsh and attaching hooks to the rope every few yards with short lines called snoods.

Once set in the water and baited (usually with salt eel), Felix Beasley would return and check the lines early every morning during the spring and summer. He’d pole his skiff along the length of each of his trotlines, lifting the line as he moved from snood to snood, and catch the crabs with one of these dip nets while the crabs nibbled on the bait.

In Colington they also caught eel with trotlines usually baited with pieces of crab. Needless to say, the practice of baiting crab trotlines with eel and eel trotlines with crab inspired more than one whimsical reflection about the futility of getting ahead in life.

When Charles Farrell visited Colington, the fishing village was, as Miles Midgette told me, a rough and rowdy place. “They liked to drink, liked to fight,” he said. He was a long ways from sounding apologetic.

He also described Colington as close-knit, caring and neighborly.

It was “a barter kind of place,” he reflected, where cash was in short supply and neighbors exchanged—and often gave freely of— their trades and all manner of fish, wild game and garden produce.

The islanders looked after the sick and elderly, and they took in other people’s children and raised them if their own families could no longer take care of them.

It was also the kind of place, Miles stressed, where a young single mother with two children and an old fisherman in declining health could make a home.

-3-

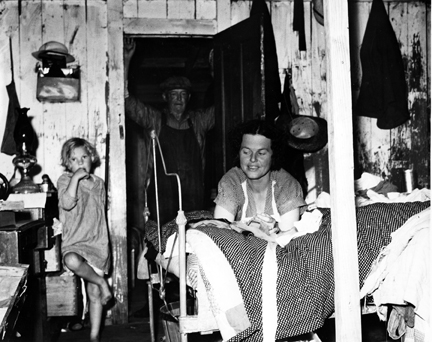

Lizzie lying across her bed, with Callie to one side and Felix standing in the doorway. She rests on a handmade quilt on a mattress held in an old tubular and wire frame. A kerosene lamp rests on a chest of drawers, clothes hang along a whitewashed partition wall.

Dark lines on the bedroom walls, most visible on the doorpost between Callie and her stepfather, may well be watermarks from hurricane flooding, such as occurred during the great storm of 1933.

Without doubt, Felix had drilled a hole or two in the floorboards nearby so that floodwaters would not lift the house off its foundation and wash it into the sea again.

A basket stored under the bed may hold potatoes.

In many ways, the Beasleys lived little differently than did their parents or grandparents. As in all of Colington, their home did not have indoor plumbing, a telephone or electricity. They cooked and heated the Houseboat with a small wood-burning stove and washed their laundry in the yard in a cast-iron pot over an open fire.

Lizzie made most of the children’s clothes by hand. They bathed in a galvanized tin tub that, when not in use, slid under the house. They lit their home at night with a kerosene lamp, possibly just the single lamp seen here.

They kept a few chickens in a pen fashioned out of discarded fishing nets, and they tended a vegetable garden, heavy with shallots and collard greens.

To get by during the Great Depression, the Beasleys and their neighbors ate a great deal of fresh and salted fish, caught songbirds with deadfall traps and ate them, and shot many a squirrel. More than anything, Joe Beasley, one of Lizzie’s children born a couple years after this photograph was taken, told me, they ate an abundance of dried beans and biscuits and gravy.

“We had plenty of food, such as it was,” Felix Beasley’s oldest granddaughter, Zenora Beasley Midgette, remembered.

She was not much younger than her step-grandmother Lizzie and grew up just down the road from the Houseboat.

When her nephew, Rocky Midgette, a graduate of Amherst College, did an oral history interview with her in 1994, she recalled that farmers from Kitty Hawk, on Bodie Island, occasionally visited Colington with sides of fresh beef and sold cuts door to door.

Few fishing families could afford to buy much beef in the 1930s, however. Neither did they drink much milk. Like all of Colington, the Beasleys had no refrigeration, and the village did not yet have an icehouse or regular ice delivery. If a mother or a sick baby needed milk, a child was usually sent to Nags Head, on Bodie Island, to fetch a pail full from a woman with a milk cow there.

As in so much of the rural South, diseases of malnutrition were not uncommon in Colington during the Great Depression. Zenora Beasley Midgette recalled, for instance, that several of her neighbors in Colington suffered from pellagra, a disease born of inadequate nutrition, when she was young.

Pellagra was endemic in the rural South at that time. Zenora’s mother died of pellagra in 1930, when she was 12 years old.

During the Great Depression, a midwife provided most of the medical care in Colington. But if a child or adult needed to see a physician, they took the mailboat to Powell’s Point, on the western side of Currituck Sound, or to Manteo, on Roanoke Island, 10 miles south of Colington.

In her interview, Zenora Midgette remembered that the mailboat’s captain, Jessie Meekins, allowed passengers to ride for no charge between Colington and Manteo. He only made one passage a day, so travelers often had to stay overnight and return on the next day’s mailboat.

Mr. Meekins also picked up medicines, clothes and other dry goods in town for those who could not make the trip.

-4-

A group of Felix and Lizzie’s neighbors, the Rogers family, sitting on the front porch of their home on Little Colington Island. The house sat just down a cart path from the Houseboat.

Alva Rogers is on the far right, her little brother Pete is on the far left, and two unidentified family members, perhaps their father and another brother, sit in the middle.

The house has not the least extravagance: even the window openings have only crude shutters, no window glass or sashes. An old church pew sits on the porch.

Peter Sandbeck, an acclaimed architectural historian who has focused much of his work on eastern North Carolina, took a special interest in the Rogers’ house when I showed Farrell’s photographs to him.

He noted that few fishermen could afford milled lumber during the Great Depression, yet the Rogers’ home was clearly new-built: the boards on the walls are freshly sawn.

The ends of the porch boards show rot, however, a sign that they built the house with a mix of lumber that they scavenged and cut themselves.

The Rogers’ home was, Sandbeck indicated, “a great example of … a plank-on-plank walled house, built very rough, locally sawn wide boards, knots everywhere. They built these with simple corner posts, sills and top plates, then filled the entire wall opening with vertical boards, one layer outside and another inside, with the boards arranged so that the inside layer covered the cracks between the outside boards.“

For that kind of building, Sandbeck noted, the Rogers felled local trees and sawed them into boards with a portable circular sawmill of a type driven either by a tractor or an automobile’s rear wheel.

“A genuine Depression era building method,” Sandbeck concluded, and one achieved with only the smallest of savings, a few simple tools and willing hands.

As can be seen on the lower right, the Rogers used tree stumps for the piers that held up the house.

-5-

“Hoop and Wire.” Brothers James Lewis Beasley, Jr. and Ralph Beasley at play on Little Colington Island. They are playing a game the village children called “hoop and wire,” using an old coat hanger and a round gill net weight.

Ask anyone that grew up in a fishing village and they will recall how they fashioned toys and playground equipment out of the tools of a fisherman’s trade: net spreads became monkey bars, beached skiffs became forts and, as with James and Ralph Beasley, gill net weights became magical hoops.

For many children on Colington, the highlight of the week, at least in distant hindsight, was the long, meandering walks that they used to take on Sundays after church. Almost to a one, the village’s oldest residents recall those Sunday rambles, all the islands’ children together, as one of the great joys of their youths.

Liberated from chores and school on the Sabbath, they’d walk and talk until dusk, stopping now and then to swing on muscadine grape vines or to slide down the big dune where Hilltop Cemetery is now.

Young James and Ralph were two of Felix Beasley’s grandsons. Felix had six children with his first wife, Elenora, who died in 1914. Those children and their many children all lived around him and Lizzie at the time that Farrell visited the island. All five of Felix’s grown sons were commercial fishermen, as was his daughter Chloe’s husband, Johnny T. Moore. These stalwart young lads, too, would one day make their livings on the water.

-6-

The Wright Brothers’ first flight, Kill Devil Hills, N.C., December 17, 1903. Courtesy, Library of Congress

A brief detour to discuss muskrats and the birth of aviation:

Johnny T. Moore, Felix Beasley’s son-in-law, was something of a reluctant celebrity on the Outer Banks. As a boy, he had been one of only five eyewitnesses to Wilbur and Orville Wright’s first airplane flight. That flight occurred on December 17, 1903, on Kill Devil Hills, the high sand dunes that rise over Bodie Island, a mile east of Little Colington Island.

Moore was 16 years old at the time. Occasionally, Outer Banks civic leaders invited him to be an honored guest at commemorations of the Wright brothers’ flight. Moore often demurred, saying that he had to tend his muskrat lines instead.

Whether or not Moore actually found his muskrat lines so time-consuming, he and other islanders did trap a lot of muskrats.

To catch the furry aquatic rodents with the rat-like tails, they poled skiffs through salt marshes and laid steel traps near the underwater openings to their dens. They marked the locations of their traps by tying knots in tufts of marsh grass.

Each islander tied a distinctive knot, which was, in effect, his brand and claim to ownership. They sold the muskrat pelts to buyers that shipped them north to be used in making coats, hats and gloves.

Some locals also ate muskrat. At a gathering of Felix Beasley’s descendents that I attended a couple years ago on Little Colington Island, his grandchildren rather un-nostalgically recalled their elders’ fondness for a plate of muskrat and collard greens.

-7-

Lizzie holding Callie on her lap in the Houseboat’s parlor. Behind them is a hand-cranked Victrola, the family’s only luxury, protected by a rumpled tablecloth and with an ironstone pitcher on top.

The Victrola was a relic, Felix’s brother Morris, also a fisherman, later recalled, of “when times were better.” On the northern Outer Banks, fishermen had enjoyed some flush years earlier in the century, particularly pound netting for shad, but those days had passed.

Catches had slumped, and the Great Depression left the Beasleys and many other local families hanging by a thread.

For many in Colington, the only reliable cash income during the Great Depression came from the Works Progress Administration (WPA), one of the Roosevelt Administration’s New Deal agencies that sponsored public works programs for the unemployed and underemployed.

Morris (pictured to the right, with Lizzie, outside the houseboat) worked for the WPA, as did at least one of Felix’s grown sons.

In the 1930s, hundreds–maybe thousands– of Outer Banks fishermen worked on WPA road paving, bridge building, anti-erosion, mosquito control, and wildlife conservation projects. Standard pay was $21 a month.

Victrolas were phonograph record players with the turntable and amplifying horn held inside a cabinet. The Victor Talking Machine Company of Camden, New Jersey, had made them since 1906.

The Beasleys purchased their Victrola from the Montgomery Ward Co., in Chicago. Along with Sears, Roebuck & Co., Montgomery Ward did its best to make consumer goods available for the first time by mail-order catalog even in places as remote as the Outer Banks. To stay affordable in tough economic times, the company offered no-money down deals and payments as low as $5.00 a month.

In 1939 Morris told a visitor that the Beasleys bought their Victrola for $145, a sizable sum to a fisherman’s family even in the best of times. That was apparently in the ‘20s, before the stock market crash and the downturn in the fishing business.

When Morris spoke with that visitor—a legendary newspaperman named W. O. Saunders from Elizabeth City, N.C.—he told him that Lizzie’s favorite record to play on the Victrola was J. E. Mainers’ Mountaineers’ version of “We Can’t Be Darlings Anymore.“

Mainer, a fiddler, was a cotton mill worker who played mountain and country music. Hailing from Concord, N.C., he often performed on radio shows in North and South Carolina in the late 1930s. He also made a few recordings.

The first two verses of Lizzie Beasley’s favorite song go like this—

Darling you often said you loved me

But you’ve gone on before

You don’t know dear how I miss you

But we can’t be darlings anymore.

Darling I am sad and lonely

Since you’ve gone on before

So down here on this lonely earth dear.

We can’t be darlings anymore.

That was a year after Felix’s death. He passed away only a few months after Charles Farrell took these photographs.

-8-

“A good man.” Ivey Beasley, probably in the lane by the Houseboat. Times were hard, and in the near future young Ivey would begin taking a share of responsibility for looking after the rest of his family.

“Ivey was out crabbing and fishing when he was 7 or 8 years old,” his widow, Carole Johnson, told me when I visited her at her home on Roanoke Island. “From the time he could push a skiff he was out there making some money.”

When I spent an afternoon with Ivey’s family and neighbors not long ago, they described him in almost saintly terms. He never drank, never smoked and was always there for those in need.

“There was a purity about him,” his sister-in-law, Bea Rollins, told me. His words always, she said, “came from his heart.”

Ivey remained devoted to his mother and sister Callie throughout his life.

Acknowledging the free-spirited, hard-drinking family in which he was reared, Carole shook her head at how things work out. “He was a good man,” she summed him up.

When Ivey Beasley died in 2010, at the age of 81, he left behind, in addition to Carole and their six children, 20 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren.

The End

Acknowledgements

For their help with this article, I would like to express my gratitude to Dru York, Peter Sandbeck, Penne Sandbeck and the staff at the Outer Banks History Center in Manteo, N.C., especially Sarah Downing, Tama Creef and Kaeli Schurr. I am also grateful to all of the Beasleys’ children and grandchildren and their families for their help, but above all Miles Midgette for being such a fine guide to Colington. Thanks also to Carolyn Johnson, Bea Rollins, Bobby Gamiel, Donis Parker, Amy Gamiel, Mark Gamiel, Henry Dean Haywood, Scott Haywood, Ray Beasley and John Beasley.

In addition, I found a pair of surprising archival sources that were very useful: Rocky Midgette’s interviews with Zenora Beasley Midgette (Colington, N.C.), dated 22 Feb., 29 Feb. & 4 Mar. 1994, at the Outer Banks History Center, and W. O. Saunders’ interview with Morris Beasley, ca. 1939, in the Thaddeus S. Ferree Papers at the Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library, Chapel Hill, N.C.

For all her help with the Charles A. Farrell Photograph Collection, I would also like to thank Kim Andersen at the State Archives of North Carolina from the bottom of my heart.

Hi David,

May I share your Article about Colington Island on my webpage with credits? I am a local realtor that has lived on Colington Island since 1984 and selling property there is one of my specialties. There is so much history about are area that needs to be discovered and shared!

LikeLike

Please excuse my typo. It should read “our” area..

LikeLike

Sure! Glad you think its worth sharing- if you d include the blog’s web address or a link that would be great! David

LikeLike

This was very interesting to me as my mother,Florence Beasley Stevens ,sister of Zenora Beasley Midgette grew up in Colington also. I would go every summer and spend the summer with my Aunt Zenora (Nornie) as we so lovingly called her and my cousins.. We also lived in a very isolated place but it was different so we thought it was great to go some where different. We lived south of Va. Beach, even further south of a place called Sandbridge. Our nearest neighbor was 5 miles away at the Coast Guard Station..We were between the ocean and bay on a strip of land that went all the way to N.C, and that is the way we traveled to Colington. Our house was built by my Dad, a fisherman at that time and it was built on the NC./ Va. line. Infact the bedroom was in NC. and other parts of the house was in Va. I was born in that bedroom in 1938 but we didn’t find out until years later that I was actually born in N.C. but was registered in Va. because at the time my parents thought it was Va. Thank you putting that article in the paper..

LikeLiked by 1 person

My goodness, what memories you have! I wish we could sit on a porch somewhere & talk all afternoon! Maybe one day! Thank you for your note!

LikeLike

I do have a lot of memories and I do wish we could sit and talk. Thank you for your reply

LikeLiked by 1 person

My grandfather Noah M. Toler was born (1895) and reared in Kitty Hawk. His sister married a Hamilton and lived on Colington Island. Her son Pat Hamilton still lives there, I believe. My grandfather always talked about how the locals used Colington as a free range corral for their cows.

In the 1980s local high school students were required to interview a older local native resident to gather the living history. You might see if you can locate some of those interviews.

Thank you for the very interesting insight into one aspect of life gone by on the Outer Banks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Herring Workers | David Cecelski

Pingback: Our Coast’s History: The Herring Workers - OBXNews.Live

Pingback: Our Coast’s History: The Herring Workers – growline.info