New Haven Museum, New Haven, Conn.

As impressive as I found Yale’s Beinecke Library, which is a modern, architectural wonder (more on that visit later), I found myself far more excited by the Whitney Library at the New Haven Museum.

Maybe I just succumbed to nostalgia. Founded in 1862 and located next to Yale, the Whitney has spectacular collections on New Haven’s history but has made few concessions to modernity.

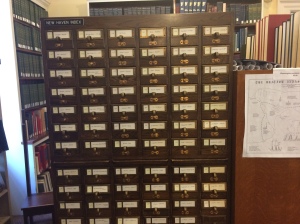

Card catalog, Whitney Library, New Haven Museum. Photo by David Cecelski

There are no high glass walls. There are no computers. Information on the collection’s holdings remains in card catalogs—which are cabinets, I guess I should explain for those of you not as old as I am, generally considered obsolete in the digital age, containing long, wooden drawers full of index cards filed by subject, author and title that refer a researcher to a book, manuscript or map’s location in a library.

I didn’t realize how much I’d miss card catalogs until they were gone: the feeling of the paper cards, evocative of old papyrus, the historical treasures one up against another, the accidental discoveries. I know it’s a little pathetic, but at the Whitney Library I felt as if I had found a long lost friend.

And then, when I asked how to find a copy of a New Haven newspaper from 1874, the reference librarian did not send me to a digital collection. She didn’t even send me to a dark room filled with microfilm or microfiche readers: she brought me the original newspapers, swaddled in wax paper.

I nearly fainted with joy.

George N. Ives, New Haven & the History of North Carolina’s Fishing Trade

The reference librarian was the key to my exhilarating experience at the Whitney Library. Frances Skelton asked me how she could assist me as soon as I walked into the reading room.

Having worked at the Whitney for more than 25 years, Ms. Skelton knew the collections inside out, and she immediately made herself a partner in my historical research.

I told her that I was interested in George N. Ives, an oyster keg, pail and barrel manufacturer who left Fairhaven, Conn., in the 1870s and became the most important pioneer in the oyster and seafood business on the central coast of North Carolina in the late 19th century.

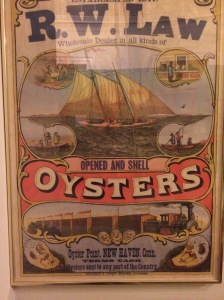

Advertisement for R.W. Law, oyster wholesalers, New Haven, Conn., late 19th century. Courtesy, New Haven Museum.

I was also interested in Fairhaven. Now only one of New Haven’s gritty waterfront neighborhoods, Fairhaven was the most important oyster port on Long Island Sound for most of the 19th century and was one of the largest oyster ports in the U.S., second only to Baltimore.

I wanted to learn more about George Ives and Fairhaven’s oyster industry because they had a significant impact on the rise of the oyster industry on the North Carolina coast.

Ms. Skelton was not familiar with George Ives, but she asked me several questions about my research and then turned and disappeared into the library’s closed shelves and vault.

She soon returned with business directories and city yearbooks from the 1860s and ‘70s.

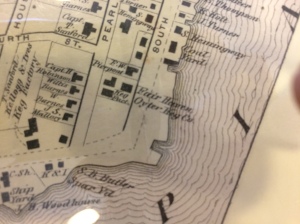

Detail of Quinnipiac River wharf and oyster district, New Haven, Conn., 1868. Courtesy, Whitney Library, New Haven Museum.

She also brought a fantastic 1868 map of the old port. I quickly found the location of Ives’ factory at the south end of Pearl Street, in a district of oyster canneries, shipyards, limekilns and oyster barrel and keg factories on the Quinnipiac River.

In one of the city yearbooks, I found records of the fire that destroyed the Kellogg & Ives’ factory on March, 11, 1874. The fire burned the factory to the ground and damaged two adjacent properties, A. Thomas & Co. and the home of a Mrs. Julia Mallory.

The fire was listed as “supposed incendiary.” From newspaper accounts I had seen years ago at the New Bedford Free Public Library, I knew that Ives had been charged with arson.

What happened to Ives in court, if he went to court, and how he ended up in North Carolina a few months later, is still a mystery to me.

Ms. Skelton asked me more questions about Ives and Fairhaven, then turned and again went into the vault.

This time she brought me a local woman’s reminiscences of Fairhaven in the late 19th century.

Later she found published histories that discussed Fairhaven in that era, as well as earlier in the 19th century, when it was known as “Dragon.” She also introduced me to manuscript records that gave insight into the town’s oyster industry.

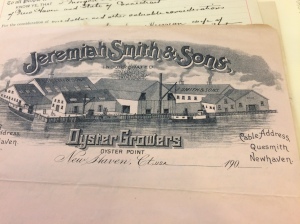

Letterhead from Jeremiah Smith & Sons, Oyster Growers, New Haven, Conn. The Whitney Library holds a fascinating collection of the company’s papers. Courtesy, Whitney Library, New Haven Museum

I found one group of manuscripts especially interesting. They were the records of Jeremiah Smith & Son, one of the many oyster companies in Fairhaven. The papers included remarkable, handwritten maps of the local oyster grounds, complete with navigational landmarks.

Another source that the reference librarian found for me was a book called Industrial Advantages of the City of New Haven, Conn. Published in 1889, the book described another Fairhaven oyster company—W. S. Robinson— and provided rich details on how manufacturers constructed the industry’s tubs, pails and kegs.

The making of fish crates and boxes, oyster kegs and salt fish barrels was an essential part of the economy in every fishing port, but I rarely find that the importance of those enterprises is appreciated.

From Fairhaven, Conn., to the NC Coast

My research at the Whitney Library unfolded at a hectic pace, as the library was due to close in a couple hours.

For me it was a lovely choreography: Ms. Skelton and I brainstormed, sometimes just for a few seconds. As soon as we set on a new path of inquiry, she turned abruptly toward the closed stacks or the vault.

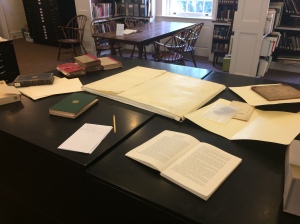

She always returned, laden with books and manuscripts, and we’d start over. We scattered the books, manuscripts and maps over cabinets that held historic maps and charts.

My research table at the Whitney Library, while you could still see the table. Photo by David Cecelski

Gradually I learned a little more about George N. Ives, and a good bit more about Fairhaven and the oyster industry.

I also began to gain a fuller picture of Fairhaven and the growth of its oyster industry in the early 19th century: carts of oysters carried from cottage to cottage, where the oystermen’s wives, widows and children shucked and stored them until the carts returned.

Then, later, the townspeople began opening oyster shucking houses and canneries. The Quinnipiac River and Long Island Sound filled with oyster bateaux, dugouts, skiffs and eventually sharpies.

A few decades later, local schooner captains began to creep ever further down the Eastern Seaboard in search of oysters for seeding. They sailed at least as far as the Chesapeake Bay, where they were responsible for founding some of the earliest oyster companies in Baltimore. They may have gone as far south as North Carolina’s coastal waters.

In time, the Quinnipiac River waterfront filled with shucking houses, canneries, giant mounds of oyster shells, limekilns, boatyards and barrel, pail and keg makers.

That was the world of George Ives’ youth. And after his factory burned in 1874, feloniously or not, he carried what he learned in Fairhaven to the North Carolina coast.

Most famously, he brought the sharpie, the famous flat-bottomed boat that became the workhorse on North Carolina’s sounds for the next 40 or 50 years.

Even more importantly, Ives introduced manufactured ice to North Carolina’s fishing business, making him one of the most important figures in the rise of the state’s fresh fish industry in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Amistad and Eli Whitney

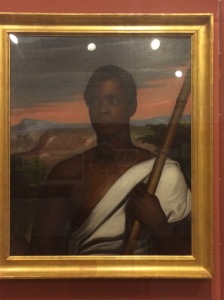

Portrait of Joseph Cinque, by Nathaniel Jocelyn, ca. 1840. Cinque was a Mende rice farmer and leader of the captives who staged a revolt and took over the slave schooner Amistad in 1839. Scholars believe that his real name, not the one given him by slave traders, may have been Singe Piah. The trial that ultimately upheld the Amistad rebels’ status as free persons was held in New Haven. Courtesy, New Haven Museum. Photo by David Cecelski, who regrets his lack of talent for photography and lighting immensely.

The Whitney Library is part of the New Haven Museum, and while I was there I explored the museum’s exhibits.

Many were enthralling. I especially enjoyed the exhibit on the Amistad incident, and another on New Haven’s maritime history, as well as seeing an early example of local resident Eli Whitney’s cotton gin.

For me, though, the Whitney Library and its old-fashioned approach to historical research—non-digital, tactile and bolstered by an exhilarating back and forth between librarian and researcher—was what I found most exciting and memorable. Once again a librarian had helped me to find my way through the deep and fog-cloaked waters of our past.

David this is fascinating of course given the sharpie connection but also what Ives’ other connections/influences. I visited the Ives house in New Bern years ago and was given a “tour” including the attic but saw nothing of interest.

Sent from my iPhone MB Alford

>

LikeLike

hey Mike, only you and I would go looking for George Ives in New Haven or New Bern! I’d love to learn where his home in New Bern was–

LikeLike

Dear David

I’ve been reading lots of your blog posts to catch up on all your work, and sharing with good friends in the mullet-oyster-agriculture communities. But this is the post that made me finally write to you. I had nearly the same experience at the Whitney Library in 2013, except I went looking for Jeremiah Smith & Sons. They were key seed oyster suppliers for the San Francisco Bay industry, and probably for the Willapa Bay, Puget Sound and short-lived Los Angeles experiments. I know little about the North Carolina story and hope to learn from you. Lots of people care about this work. Thanks for doing it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great to hear from you, Matthew– really glad to hear that my work might be useful to you. Let me know if there’s anything else I can do for the project– I haven’t written a lot about the oyster industry in N.C., but there is a chapter in my book A Historian’s Coast on the boom years from ca. 1880-1920. Also, other things scattered in various articles– like my piece on Portsmouth Island’s oral histories that’s on this site!

LikeLike