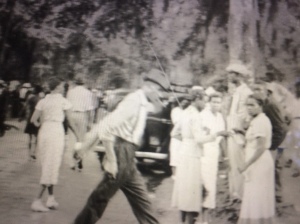

Independence Day celebration, Lake Waccamaw, early 20th century. Courtesy, Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum

This is the first in a special series on Jim Crow and our coastal waters. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be posting at least 8 stories about coastal North Carolina’s forgotten history of all-white beaches, “Sundown towns” and racially exclusive resort communities. You’ll eventually be able to find them all at The Color of Water.

A memory. I am remembering a visit to the Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum in the little town of Lake Waccamaw, in Columbus County, N.C. The town is built on the north side of Lake Waccamaw, a broad, shallow, circular lake that is the kind that people here call a “Carolina bay.”

It’s one of my favorite places to go anywhere in North Carolina. The lake is beautiful. On the south side of the lake is also one of the largest, wildest and loveliest bottomland swamps in North America.

I was there that day to give a lecture at the museum, which occupies the town’s old railroad depot. When I finished, a woman in the audience greeted me and introduced herself. That was years ago, and I’m afraid that I have lost her name, but I remember that she lived in Wilmington, but she had grown up at Lake Waccamaw and often returned home.

She and I chatted awhile about Columbus County’s history, and we also talked for a few moments about what it was like for her growing up African American at Lake Waccamaw.

Sporting a vintage swimming outfit, local historian Ernestine Keaton, of East Arcadia, read her article on the history of Lake Waccamaw’s Independence Day celebration. That article spurred the museum’s gathering. Photo courtesy, Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum

As we parted, she handed me a DVD and told me that it was a recording of a panel discussion that had recently been held there at the Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum. She said the panel discussion focused on what used to be one of the most special days for people of color in all of southeastern N.C.: Lake Waccamaw’s annual celebration of Independence Day.

In the Jim Crow Era, she said, the Independence Day celebration was the biggest event of the year for local African American families. The celebration was held every summer roughly from 1911 to 1937, and as many as 16,000 people came to the shores of Lake Waccamaw on that special day.

Homecoming

It was a patriotic pageant, church homecoming and family reunion all rolled into one. Everybody came home for it. Countless numbers of black Carolinians had left southeastern N.C. during the Great Migration, but they came back for Independence Day at Lake Waccamaw!

They made the long trip from Philadelphia, New York, Washington, DC, Newark, Cleveland and everywhere else that the region’s black and Indian people had gone in search of a better life.

Independence day crowd at Lake Waccamaw, early 19th century. Courtesy, Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum

The Atlantic & Coastline Railroad ran special excursions for black passengers, making it the one day of the year when black riders didn’t have to live with Jim Crow seating on the trains— for the Independence Day celebration, the riders were all black.

Farm trucks crowded down with 15 or 20 riders rumbled into town, too. Many, many other people came straight out of the tobacco fields in wagons and carts pulled by a mules.

They swam and fished on the lake, and they ate hefty picnic boxes full of mouth-watering, home-cooked Southern food: lots of fried fish, chitlins and all kinds of good old-fashioned soul food.

Most people brought big box dinners, but vendors also sold homemade candy, fresh lemonade and other treats. If you were looking for it, you might find a little stump liquor, too.

Young people courted, walking back and forth under the oaks and cypress trees on the path between the railroad depot and the lake. Others strolled the boardwalk that rimmed that side of the lake.

There were baseball games, people waded into the lake, and no doubt some went swimming.

You could take a boat excursion out on the lake, and at night there was a dance at the two pavilions built out over the lake.

A gathering at the Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum

I learned some of this from the very nice woman who gave me the DVD at the Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum, and I learned some of this when I went home and watched the DVD.

The panel discussion on the DVD was really special. The panel included a fabulous octet of African American elders who remembered the Independence Day celebration at Lake Waccamaw.

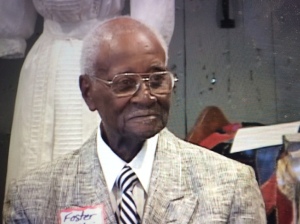

Mr. Foster McClain, of Whiteville, N.C., age 89, recalled his childhood visits to Lake Waccamaw’s Independence Day festival. Courtesy, Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum

The group included Clarence Hall, Francis Jones-Isler, Foster McClain, Vivian Smith, Carl Stanley, Colene Stanley, Charles Ward and Ida Young.

The oldest, Mr. McClain, was 89 years old. Most were in their 80s. Some of the panelists grew up in the African American and Indian communities at Lake Waccamaw.

Others hailed from other parts of southeastern N.C. All had come to the Independence Day celebration at Lake Waccamaw when they were children.

Three others also contributed to the panel discussion.

Ginger Littrell had done some wonderful research on the Independence Day celebration in the local newspapers. At that time, she was the museum’s director. She read excerpts of the newspaper articles to the gathering.

A second woman, a retired teacher named Mary Mintz, had recently advised a group of students that had undertaken an oral history project about Lake Waccamaw’s past.

The students had interviewed a number of African American elders about their memories of the Independence Day celebration. Ms. Mintz shared some of those conversations with the audience.

The third woman, Ernestine Keaton, came in style: she wore a bathing outfit of the utterly proper kind that a lady might have worn at Lake Waccamaw in 1910! (though she left off the leggings so you could see her ankles! Scandalous!)

Ms. Francis Jones-Isler, age 88, telling stories at the Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum. To her right is another panelist, Ms. Ida Young. Courtesy, the Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum.

Ms. Keaton was too young to recall the Independence Day celebration at Lake Waccamaw, but she had spoken with many of her elders who had gone when they were children.

As part of the panel, she told some lovely and very funny stories about her mother’s memories of going to the celebration.

Ms. Keaton is from East Arcadia, 15 miles from Lake Waccamaw in Bladen County. Dedicated to preserving and sharing the African American history of Bladen and Columbus County, she had written a newspaper article about the Independence Day celebration. Her article had first kindled interest in organizing the panel at the Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum.

Like lemonade, sweet but tart

Ms. Keaton seemed best to capture the spirit of the Independence Day celebration. It was, she said, “like lemonade, sweet but tart.”

The sweetness, of course, arose from the memories of the joyful good times at Lake Waccamaw with so many friends and family from all over southeastern N.C. and beyond.

The tart was the historical context for the African American celebration of the 4thof July there at Lake Waccamaw.

Mr. Charles Ward at the Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum. Born in Lake Waccamaw, he remembered the last years of the July 6th Independence Day celebration. Courtesy, Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum

Because behind the sweet memories, there were also this reality: the 4th of July celebration at Lake Waccamaw didn’t actually happen on the 4th of July—at least not for African Americans and Indians.

On the 4thof July, whites had their 4thof July celebration. It was smaller than the black celebration, but still drew sizable crowds from as far away as Wilmington, N.C.

People of color were not allowed to visit the lake on the 4th.

Then, two days later, on the 6thof July, the African American community held its celebration of Independence Day.

There was also this reality: when state and local officials closed Lake Waccamaw to the African American celebration in 1937, they said it was “for sanitary reasons.” But the white celebration continued.

At least one of the panelists at the Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum also remembered this: in 1937, when some black individuals saw the new “closed” signs for the first time and tried to visit the lake anyway, local police or highway patrolmen beat at least two of them, a man and a woman.

And then there was this reality: during the Jim Crow era (1898 to the 1960s), white leaders did not allow black or Indian people to use Lake Waccamaw any other day of the year.

Their children could not swim in the lake. They could not fish on its shores. They could not walk on the boardwalk or go to the dances in the pavilions. They could not launch a rowboat or a sail skiff. The 6thof July was the one and only day of the year when the lake belonged to them.

Jim Crow on the shore

That was something that I would not forget. To me Lake Waccamaw’s July 6th celebration opened up a much bigger story: a saga about the history of Jim Crow and issues of access to the water in North Carolina’s coastal counties that I did not fully understand and that, after going to Lake Waccamaw, I thought needed to be looked at more deeply.

And I don’t just mean the history of Jim Crow around our coastal lakes such as Lake Waccamaw, but also on our rivers, sounds and seas, as well as at our beaches and beachfront communities.

So after visiting the Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum and watching the DVD recording of that incredible panel discussion, I began a file on the history of Jim Crow and the water both in the parts of the N.C. coast where I grew up and in some of the more far-flung corners of eastern N.C.

Whenever I met older coastal people, I asked them about their memories of Jim Crow days at the coast.

Also, when I was researching other coastal subjects at archives and libraries, I kept an eye out for historical accounts that might shed light on Jim Crow and the way it has shaped our beaches, our waterfront resorts and our seaside communities here in North Carolina.

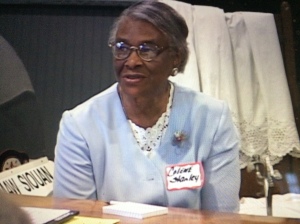

Mrs. Colene Stanley recalled her mother’s 6th-of-July picnic dinners. Courtesy, Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum

Over the next few weeks, I’ll be sharing what I heard and what I learned here on my blog.

Sometimes I think that one of the reasons that people come to the beach is to get away from the burdens of the past wherever they call home, but these stories will reveal that there’s really no escaping the past.

The story of Jim Crow on the North Carolina coast is a tale of segregated beaches, “Sundown towns,” dispossession and sometimes forced removal.

It is also a tale with a great deal of persistent struggle and determination. Despite Jim Crow, African Americans and Indians often found ways to enjoy our coastal waters, to see their children knowing joy and happiness by the shore, and to renew a lasting and soul-deep connection to the sea.

Some of their historical experiences of Jim Crow and our coastal waters were, as Ernestine Keaton said in Lake Waccamaw, “like lemonade, sweet but tart.” And others, let’s face it, were just all tart.

At the Lake Waccamaw Depot Museum, I learned that I had a lot more to learn about our coastal waters and the Jim Crow era. Over the next few weeks, I’ll share some of what I have learned here.

And as always, if you have stories that shed light on this important and too-long-neglected subject, I would love to hear them.

I know I have just scratched the surface in my own research, and I always look forward to learning more about this coastal world that I still call home, no matter how sweet or how tart.

To be continued—next time, Part 2– Swansboro

I am wondering what dance pavilions were there at that time. The ACL had erected two “shelter house” type pavilions near the waterfront and the Waggaman Hotel had a grand pavilion out over the water. I think there may have been another one. Don’t know how we would find out which pavilions were used for the 6th dances. No one around to ask, anymore.

LikeLiked by 1 person

yes, to me that’s why the museum’s panel was so important– it was the last chance we had to preserve that history! i know there’s unanswered questions, but you all did such a great thing to preserve so much of the story while there were people still alive that remembered it!

LikeLike

Did you have Melba Wyche for your English teacher? Mary Mintz? I understand you are a grad of “Bogue University!”

Get Outlook for iOS ________________________________

LikeLike

My great uncle had given me the book Along Freedom Road many years ago. I am so glad he did. This series is outstanding! Keep up the good work. It is needed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your good words, Earline- David

LikeLike

My mom is Colene Stanley. She passed May,2018 at the age of 94. Love your research. Too bad we don’t have more history for our people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for writing and for your kind words about the story. I’m very sorry to hear about your mother. I know you miss her. I hope I can keep writing in a way that you and she would like….

LikeLike

Yes, maybe you are not aware of Jones Lake in Bladen County NC…versus White Lake! Or Atlantic Beach SC… versus Myrtle Beach! I remember!! AND, not much has changed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for writing– I bet you have some stories about Jones Lake and White Lake! I’ve written a little about Jones Lake, but not much– https://davidcecelski.com/2018/07/13/the-color-of-water-part-7-from-ocean-city-to-rainbow-beach/ — also this story– https://www.ncpedia.org/listening-to-history/powell-sallie-0. Thanks again for writing– I weep for this country sometimes….

LikeLike

Pingback: A History of Racial Injustice | Ekklesia Church

Thank You David for writing this!! Many of the people interview I know personally and remember them from my youth. They were all friends with my family who lived at the Lake. I currently in Grad School doing a genogram and this has been helpful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I grew up in Lake Waccamaw and I own the land where the segregated school was built. The hand water pump is still on the property. I’ve been doing some family research and that area’s history is fascinating. One glaring thing that I found was the very early relationships between whites, blacks, and natives were not what I thought. I would love to connect with you to learn more and to share what I have learned.

LikeLike

I’d be glad to hear from you, Mr. Andrews. You can email me at david.s.cecelski@gmail.com.

LikeLike