The house where Susan Johnson stayed during the Christmas holidays in 1800-1801. The house was originally built ca. 1735 in Campbelltown (later Fayetteville), N.C. Peter Mallett moved into the house in 1780. Known as the Mallett-Rogers House, it was moved and now sits on the grounds of Methodist College, Fayetteville. Courtesy, Council of Independent Colleges, Historic Campus Architecture Project

On the 21st of December 1800, Susan Johnson left New Bern, N.C. Her husband, Samuel William Johnson, had re-joined her, and they traveled together. Three days later, on Christmas Eve, they arrived in Fayetteville. Though the state’s largest inland town, Fayetteville was still only home to roughly 2,000 people, including both free citizens and the enslaved.

That night the Johnsons settled into the home of Peter and Sarah Mallett, whose invitation had drawn Susan to North Carolina from her home in Stratford, Conn., in the first place.

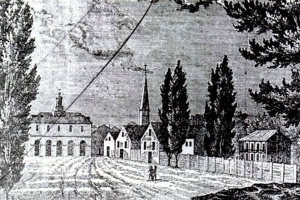

The Town of Fayetteville, 1800

Etching of Fayetteville with the Old State House in the distance, ca. early 1800s. The building burned in the great fire of 1831. The original sketch on which this etching was based was said to have been drawn by a passerby and given to the Marquis de Lafayette on his visit to the town in 1825. Courtesy, N.C. Museum of History

On Christmas Day, Susan got her first look at the town of Fayetteville.

Christmas day. A delightful day; took a walk after breakfast to see the town—most of the houses small & slightly built…. [also] a state house built for the accommodation of the legislature which sat here for some time….. the building is of brick & stones on pillars…. The under part served for a market place & the upper, for a church, as there is no Church in this place.

The “State House” had been built in 1778 to accommodate the General Assembly in the case that Fayetteville was chosen as the new state’s capital. That did not happen, however. At the Convention of 1788, delegates instead chose Raleigh as the state’s capital.

As Susan noted, the General Assembly did meet at Fayetteville’s State House “for some time”— that was in 1789, 1790 and 1793.

For local blacks, the State House—and later its replacement, the Old Town Hall or Market House—was a potent symbol of terror and cruelty: it was one of a number of local sites where African and African American people were bought and sold.

In 1800 more than a quarter of the people residing in Cumberland County were enslaved.

The African Meeting House & Fayetteville Academy

On a related point, Susan was mistaken when she wrote in her diary that Fayetteville did not have a church at that time. While Presbyterians still met in the State House, a freeborn black Methodist minister and cobbler named Henry Evans had recently founded the city’s first house of worship, the African Meeting House.

The congregation had its own small building and included both black and white worshippers, though they sat separately.

Evans Metropolitan AME Zion Church, Fayetteville, N.C. Founded by the Rev. Henry Evans, the church sits on the site of the African Meeting House that had been built shortly before Susan Johnson’s arrival in the town in 1800.

In her diary, Susan continued to describe her Christmas Day walk through Fayetteville.

There is a court house [sic] & academy at present… There is a beautiful stream running thro’ the center of this town; it has very high banks and very rapid. There are five grist mills [sic] within sight as you stand upon the bridge. A branch of the Cape Fear River runs on the East side of this town. The banks are extremely high.…

The “academy” mentioned in Susan’s diary was Fayetteville Academy, which was located on Green Street, one of the town’s two main thoroughfares. A Presbyterian minister named David Kerr was the schoolmaster.

Chartered in 1791, the school was Fayetteville’s first. The school accepted males and females, but did not accept children of color, either those that were born free or those that had been enslaved.

The Highland Scots

This is a town of great business; a great proportion of the inhabitants are Scotch; who are all plodding people & many very wealthy….

Scottish immigrants had been a strong presence in that part of Cumberland County since the mid-1700s. After the Tuscarora War and the Yamasee Wars resulted in the subjugation of the region’s native peoples in the 1710s, large numbers of Highland Scot, Scotch-Irish and Welsh immigrants had colonized the upper part of the Cape Fear River.

Gaelic speaking and Presbyterian, immigrants from Campbelltown, Argyll and Bute, Scotland, established two towns on the banks of the Cape Fear, a little more than 90 miles upriver from Wilmington.

There were also at least some Scotch-Irish and English immigrants among the two towns’ first colonists.

Those two towns, Campbelltown and Cross Creek, merged in 1778. In 1783, the new town was named Fayetteville in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette, the young French military leader who fought with the Patriots during the American Revolution.

The Old Bluff Presbyterian Church, Wade, N.C. While the church was first established in 1758, the congregation did not raise this Greek Revival building until a century later. Image from Flickr user Gerry Dincher.

If you explore that part of the Cape Fear, you will still find some of the Highland Scots’ earliest Presbyterian congregations, such as the Old Bluff Church in Wade. Though that congregation’s current building only dates to the mid-1800s, the church was first organized in 1758.

In some of those churches’ cemeteries, you will also discover gravestones with Gaelic inscriptions for the first generation of Highland Scots, as well as, in some cases, for their enslaved African workers.

I’m not sure what to say about Susan Johnson referring to the Highland Scots as “plodding.” I might note that in 1800 the meaning of the word “plodding” leaned a bit more heavily than it does today on describing an individual who, while dull or stolid, was also determined and willful.

A Slave Trader and a Smuggler

Susan also discussed the Mallet family in her diary. Peter and Sarah Mumford Mallet had a total of 15 children– 12 lived past infancy, eight still lived with the couple when Susan was their guest.

Mr. Mallett very much the man of business; very frank & agreeable in his own house . . ..

Peter Mallet (1744-1805) was the kind of man that often flourished in North Carolina’s early days. He was rapacious, an opportunist, an adventurer and a risk taker, adept at navigating colonial wars, trade embargos and tariffs in order to make a profit.

In and out of debt and often on the edge of bankruptcy, he eventually accumulated a small fortune in plantations, mercantile business and slaves.

Like most of the state’s early planters and merchants, he was also a man who took for granted that his success would be grounded in the buying, selling and owning of other human beings.

As the captain of a merchant ship, Mallett had been a slave trader on the Guinea coast of West Africa. He sold enslaved people in the West Indies, and he smuggled goods into Mexico and probably elsewhere in the Americas and Europe as well.

He was wounded repeatedly, sometimes by those trying to catch him and once in a duel. On one occasion, at Cape Hatteras, he was shipwrecked.

He parlayed his shipping profits and the insurance from that shipwreck into establishing himself as a leading commission merchant in colonial North Carolina. He originally opened for business in Edenton and later in Wilmington and Fayetteville.

Detail from map of Fayetteville, N.C., ca. 1825, by Peter McRae. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

During the Revolutionary War, he was named a commission agent for state militia and for Continental forces. He seems to have upset everybody: both Tory and Whig mobs attacked Council Hill, his plantation near Campbelltown (later Fayetteville).

Specifically exempted from the N. C. General Assembly’s Act of Pardon and Oblivion in 1782, he was tried for treason after the war, but acquitted.

By 1800 Mallett owned large estates and held many Africans and African Americans in bondage. He owned lots in Fayetteville, a rice plantation called Peter Point near Wilmington and other lands along the Black River (where Susan’s husband was working), at the very least.

He also ran a stagecoach line between Fayetteville and Wilmington, and possibly on other routes as well. Enslaved men drove the coaches.

Shared roots might explain how Peter Mallett and Susan’s husband, Samuel William Johnson, found one another and went into partnership. Mallet had grown up in Fairfield County, Conn., which was the location of the town of Stratford, Samuel and Susan’s hometown.

In addition, Mallett’s first wife, Mary, was an Edwards– Susan’s maiden name– and she was from Stratford, Conn. I haven’t yet been able to show common ancestry, but it’s possible that they were cousins and had come to know one another through Mary Edward’s family.

Romantics and Revolutionaries

In the first few days of the New Year, Susan filled her days with social visits, walks and reading and writing letters.

On Jan. 3, 1801, after her husband left Fayetteville and returned to his labors on the Black River, she walked down to Cross Creek. Two days later, she and Sarah Mallett paid a call on a Mrs. Broadfoot in the morning, and then they “went to drink tea with Mrs. Anderson.”

Sarah Mumford Mallett (1765-1836) was one of the women with whom Susan Johnson read The Old Manor House. Oil painting, unattributed, contributed to the web site findagrave.com by Mike Mallett

After tea with Mrs. Anderson, Susan came back to the Malletts’ home and read a novel aloud “to the ladies.”

Once again Susan’s taste in literature intrigues me. This time she was reading a novel called The Old Manor House. As with the other novels that I discussed her reading when she was in New Bern, a British woman who looked critically at women’s roles in society also wrote this one.

The author of The Old Manor House, Charlotte Turner Smith, was an English romantic poet and novelist whose work was widely read in the late 18th century. She was a friend of such well-known women writers as Ann Radcliffe and Jane Austen. A number of the most important romantic poets, including William Wordsworth and John Keats, considered her an important influence.

Smith’s novels often reflected her own life situation as a single mother (she had left her husband), as well as the radical ideals of the French Revolution.

Charlotte Smith, by George Romney, 1791.

First published in 1794, The Old Manor House is is actually set during the American Revolution and is a love story that, to quote a recent edition’s description, “critiques a society in love with money at the expense of its most vulnerable members, the dispossessed.”

Reading Between the Lines

In her diary, Susan Johnson says a great deal about her travels in coastal North Carolina— what she saw, what she did, with whom she had tea or took a walk.

But there are also many silences. Every time I think about the novels and other books that she was reading, I ask myself: what was going on in her mind as she traveled to New Bern, Fayetteville and Wilmington?

At those times, I wonder how Susan thought about her own status as a woman in America. I wonder about her marriage, too. What drew her repeatedly to those women novelists who wrote about– and often were– vulnerable women that had left their husbands, or been abandoned by them, and had to raise children and make livings on their own?

I also wonder, what inspired Susan to read novels in which men’s laws and the whims of men’s estate settlements and last wills and testaments so often confined women’s dreams and damaged their futures?

What drew her again and again to novelists and other writers who wrote stories that inherently critiqued women’s low status in society?

I also could not help but wonder what led Susan to read books that embraced the radical beliefs of the French Revolution, such as Charlotte Turner Smith’s The Old Manor House?

Or, as I discussed in part 5 of this series, I wondered too what led her to read to herself—and others— books such as Constantin de Volney’s Travels in Syria and Egypt that called for the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade and the liberation of all enslaved peoples.

I am not going to pretend that I understand Susan Johnson’s mind during those years of 1800-1801.

But the more I read the entries in her diary, the more I felt as if she kept her inner life out of its pages. Perhaps she kept those most private thoughts to herself in the same way that she never wrote about her husband in her diary at all, except to say when he was coming and going.

In the end, I find it hard not to feel that another woman, another Susan Johnson, remains hidden from the world, and maybe from herself as well, somewhere deep in this diary.

Next time—part 8—Susan Johnson travels to Wilmington and the Black River

Hi David I appreciate all the wonderful email.

Do you do other family history?

Sincerely,

Janet Jones-King

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Janet– sometimes! — ideas?

LikeLike

Questions, questions. Love your questions. And that you’re reading between the lines. (Would love to see a line or two from

the diary.). Perhaps Susan felt her diary was not as private as it was supposed to be. Perhaps she felt the urge to write, to share, but felt it was no safe to be totally transparent and revealing. Thank you for questioning the text. Thank you for giving context to the realities going on around Susan’s existence. Do we ever get to really know another? Now, the reader must

draw her own conclusions.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beautifully written account of Susan’s visit to the home of Peter and Sarah Mallett, my fifth great-grandparents. I am not very proud of this relationship but would rather know the historical truth.

LikeLiked by 1 person