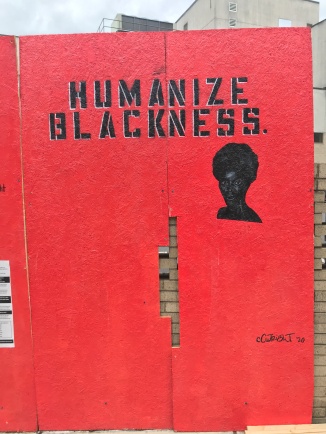

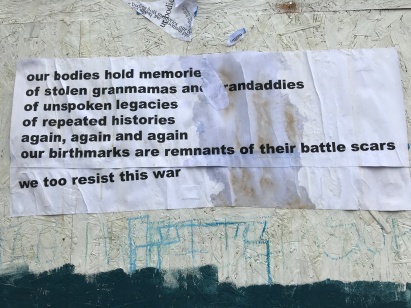

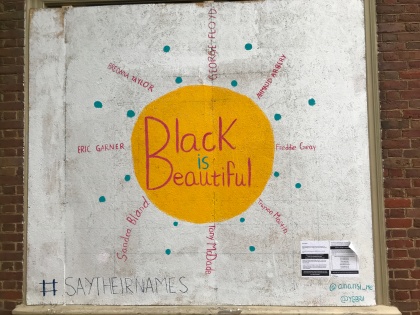

Downtown Durham, June 15, 2020. All photos by David Cecelski. Artwork credit: Shay Hendricks / IG: @shayondisplay / CashApp: $sfh99 and

Anthony Patterson / IG: @signedbyap / Paypal: info@aipatterson.com / CashApp: $aipatter

The story is part of an occasional series on the historical roots of North Carolina’s racial divisions.

In today’s post, I want to reflect a little bit on our history and how we got here– how we came to be such a divided people, why our racial divisions seem to run so deep and why our country remains the land that James Baldwin once called “these yet-to-be-United States.”

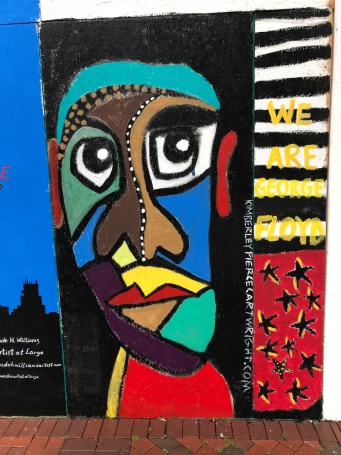

I know these questions are on many of our minds these days. As a historian I suppose I might think about them a little more than most people in normal times, but I think we’re all grappling with questions of race and history more than ever since the murder of George Floyd three weeks ago.

Artwork credit: Craig Cutright / IG: @craigcutright / Venmo: CraigCutright

Of course I don’t have any magic answers. But I do think we can learn some important lessons from the past that can help us to understand better how we came to this juncture in our history.

“Six thousand people either participated in the great Red Shirt rally at Lumberton today or stood by and cheered those who took part. It was designed to make this the greatest meeting of the most remarkable campaign for white supremacy…. The people are to vote on the second of August on the question of disfranchising the negro vote….”

Richmond Times, July 20 1900

And perhaps, if we understand what led us here, we can move forward and see more clearly where to go from here.

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced,” James Baldwin also wrote.

My historical research focuses on the history of North Carolina, where I have lived all my life. And if I was going to pick a single moment in my home state’s history that shaped our current racial dilemmas and political divisions, I would go back 120 years, to the summer of 1900.

Artwork credit: Kimberley Pierce Cartwright / IG: @kimberleycartwright / Paypal: cartwrightkimber@aol.com

That summer a mass movement of self-proclaimed “white supremacists” rose up across North Carolina with the goal of passing a state constitutional amendment to end black voting rights.

They sought to eliminate black voting rights forever. But perhaps just as much, they sought to break apart fragile bonds that black and white citizens had forged in the 1890s.

To that end, they waged a campaign that intentionally divided us, pitting neighbor against neighbor and setting us one against another. And they did so all for their own political gain, to take power and to hold it.

Artwork credit: Megan Easterling / IG: @majesticincognito / CashApp: $meggymegz93

They won and to a large degree they created our modern political system and culture.

I don’t think we have ever fully mended or healed from what they did to us.

In today’s post I will try to tell that story and why it matters so much today as briefly as I can.

Artwork credit: SpiritHouse members (in progress photo)

Building a Wall between Black and White

It’s always hard to know where to start a story about the white supremacy campaign of 1900, when its historical roots in America go so deep.

But for this story I’m going to start in 1894, when black and white voters here in North Carolina rather remarkably crossed the “color line” of the period and found enough common cause to join together and form a political alliance.

They not only succeeded in throwing out the conservative “old guard,” but between 1894 and 1896 they elected the governor, the majority of the legislature, both U.S. senate seats and a majority of other state and local officeholders.

It was far from being a radical, interracial experiment in democracy, but it was an important sign of progress.

In response, white leaders in the state’s Democratic Party began to lay the groundwork for the white supremacy movement late in 1897. The first stage saw a statewide election victory, won with a great deal of violence and electoral fraud, in November 1898.

That first stage of the white supremacy movement culminated with a political coup (the only one in U.S. history) and the massacre of black citizens in Wilmington on November 10, 1898.

After gaining power in 1898, the white supremacists in the state legislature passed a constitutional amendment aimed at making it impossible for black and white voters to make common cause again.

Artwork credit: Marcella Camara / IG: @mars.is.bored / Venmo: @marcelladc and Derrick Beasley / IG: @brobeas / CashApp: $beasleycashapp / Paypal: beasley.derrick@gmail.com

That was the disfranchisement amendment. In order to abolish black voting rights, the amendment’s provisions included a poll tax, a “grandfather clause” and a literacy test.

You can find a good overview of the disfranchisement amendment of 1900 here. You can find the actual text of the amendment here.

The state’s legislature wrote the amendment to be “race neutral” (to use a modern term) in order not to flout the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

However, the white supremacy movement’s leaders never intended to apply the amendment’s provisions equitably. They only intended its restrictions on voting to apply to black citizens.

“The whites make no secret of the fact that the amendment to the Constitution to be voted on, if adopted, disfranchises only black men. They state this openly at all their meetings, and it proves a very effective argument in winning over the whites who cannot read or write.”

Richmond Times, July 20 1900

When it came to the literacy test, for instance, the amendment’s supporters promised white voters that poll keepers would fail all (or nearly all) blacks, no matter how well they could read and write, and they would never fail whites, no matter how illiterate they might be.

They were true to their word.

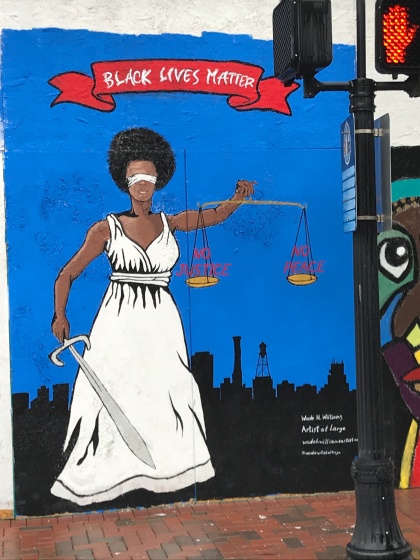

Artwork credit: Wade Williams / IG: @wadeartistatlarge / CashApp: $WHW2060 / Paypal: Paypal.me/wade272

“The Blood that will be Spilled”

After the General Assembly passed the disfranchisement amendment in 1899, the white supremacists took the amendment to the state’s voters for ratification. An election was set for August 2, 1900.

To build support, the white supremacists held rallies in more than 60 of North Carolina’s cities, towns and rural crossroads.

From the mountains to the coast, the crowds were enormous.

Some small towns could barely hold the crowds. In Gatesville, for instance, just below the Virginia line, 3,000 people, many of them on horseback, gathered on the edge of the Great Dismal Swamp.

“An audience of over 3,000 people at Gatesville, N. C, today heard campaign orators talk of white supremacy till it was shaken by great waves of enthusiasm. Pretty women with white dresses and red ribbons applauded merrily.”

Daily Times (Richmond), 27 July 1900

Leaders of the white supremacist movement were– or became– some of the state’s most illustrious figures.

Artwork credit: Anansi Stephens / IG: @anansi_me / Venmo: @anansi-stephens and Bri / IG: ygbrii / Venmo: @BriannaDuckett

During that campaign to end black voting rights in 1900, the movement’s most effective speakers included six past or future governors of North Carolina—Charles Aycock, Robert Glenn, Cameron Morrison, Thomas Jarvis, William Kitchin and Locke Craig.

“Among the inscriptions on banners and streamers were noticed the following in big, easily read letters: `Peace and prosperity.’ `White men for amendment.’ `All coons look alike.’ ‘White Supremacy.’ `Save North Carolina.’ `Protect our women.'”

Daily Times (Richmond), 27 July 1900

Charles Aycock, a Goldsboro lawyer, was the white supremacy movement’s most popular leader. He was the Democratic Party’s candidate for governor. Wherever he went, crowds of “Red Shirts” accompanied him.

Artwork credit: Unknown

“Charles B. Ayrock. . . was the star orator at the meeting today. . . . His trip from Hamlet to Lumberton was a series of ovations. With him were three or four hundred men wearing red shirts, red ties and badges announcing that they favored white supremacy.”

Richmond Times, July 20 1900

The Red Shirts were a combination of a white vigilante group, a paramilitary force and an arm of a political campaign.

They protected white supremacist speakers, harassed and assaulted Aycock’s opponents and terrorized the homes and businesses of citizens of all races that did not support the disfranchisement of black voters.

In the Gatesville rally, a former Confederate general, William Paul Roberts, described how he saw the symbolism of the color red.

“General Roberts says the red-shirted men and red-ribboned women who appear at the big meetings come in that color because it is emblematical of the blood which will be spilled if necessary.”

The Virginian-Pilot, July 27 1900.

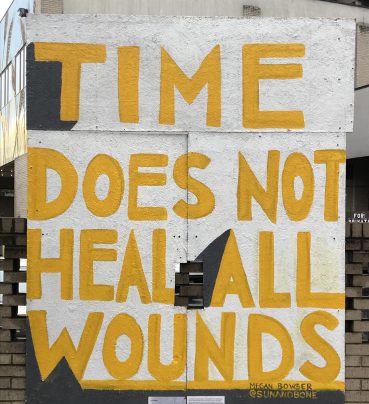

Artwork credit: Megan Bowser / IG: @sunandbone / Venmo: @sunandbone

“When Lumberton was reached about one thousand men wearing the red shirts and on horseback were lined up to receive the orator. Back of them were thousands of people backed up in the main street of the pretty little town. Women were almost as numerous as the men, and just as enthusiastic….”

Richmond Times, July 20 1900.

The Red Shirts were somewhat like the Ku Klux Klan, but they dressed in red, not white.

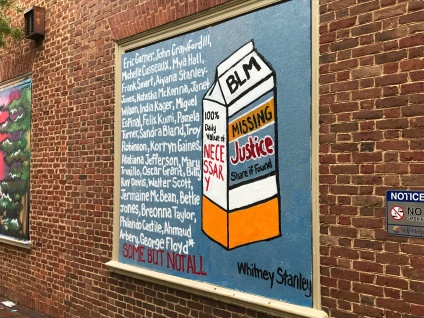

Artwork credit: Whitney Stanley / IG: @deannastnly / Venmo: @Whitney-Stanley

“A great parade was organized, and, headed by a band of music, went through the streets, while the people yelled and cannon boomed. Preceding the carriage which contained the orator, were four wagons drawn by white horses and loaded to their capacity with lovely maidens dressed in spotless white. The horses and vehicles were decorated with red colors.”

Richmond Times, July 20 1900

Unlike the Klan, the Red Shirts did not cling to secrecy or anonymity. They operated in the light of day.

Artwork credit: Unknown

“One of the biggest red shirt demonstrations. . . was at Kenansville and Warsaw, Duplin County, . . . to-day. An escort of one thousand men wearing red shirts and many of them carrying Winchesters and breech loading guns, escorted Hon. C. B. Aycock from Warsaw to Kenansvilie, where he spoke to 6,000 or more people.”

Daily Times (Richmond), July 27 1900.

“The Chieftain of White Supremacy”

According to Furnifold Simmons, a lawyer and ex-congressman from Pollocksville, he and other white supremacist leaders also organized approximately 1,000 “White Supremacy Clubs” in North Carolina that summer.

Artwork credit: Eric Cabbell, Jr. / IG: @e.cabbell.1

Their job was to rally white supremacists to the polls, and in many cases to do whatever was necessary to discourage either blacks or whites who opposed disfranchisement from voting.

“Aycock was met by a procession more than half a mile long, including 500 Red Shirts on horseback and several hundred others on foot. There were a number of floats, on which young ladies rode, the floats being emblematic of various campaign issues, white supremacy dominating.”

Burgaw, N.C. From Richmond Times, July 28 1900

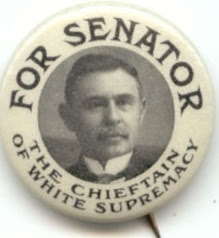

In recognition of his leadership in the white supremacy campaign, Simmons was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1900.

Simmons represented North Carolina in the U.S. Senate for 30 years. During that time, he was arguably the state’s most powerful political figure.

You can see one of his campaign buttons here:

Campaign button for Furnifold Simmons. Courtesy, N.C. Museum of History

“The negro has no more right with a ballot than a two-year-old child with a pistol.”

James H. Pou, Raleigh lawyer and real estate developer, Daily Times, July 27 1900

“Death in the pot”

While Simmons and many others played pivotal roles in the disfranchisement campaign, it was Aycock that seemed to be everywhere.

In a single 18-day stretch in July 1900, Aycock appeared at 18 rallies in 17 counties, stretching from Wake County to Carteret County.

At those rallies, speakers often threatened to kill or otherwise terrorize black citizens.

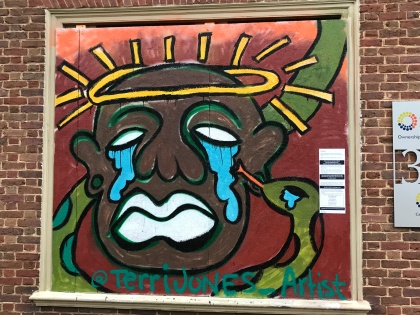

Artwork credit: Terri Jones / IG: @terrijones_artist / CashApp: $teethehooligan

As Aycock later said:

“[The Negro] may eat rarely of the cooking of equality, but he will always find when he does that `there is death in the pot.’ Let the negro learn once for all that there is unending separation of the races….”

Aycock to the NC Society of Baltimore, Dec. 18, 1903

The white supremacists also targeted white citizens who stubbornly refused to betray their black neighbors.

William “Buck” Kitchen, an ex-U.S. Congressman from Halifax County who once described himself as “a militant Baptist,” made that clear when he addressed the rally in Gatesville that I mentioned earlier.

“If a [white] man takes [the side of] negro equality in Halifax [County], the worms must eat his body.”

W.H. “Buck” Kitchen. The Daily Times (Richmond), July 27, 1900

Artwork credit: Taye Beasley and SpiritHouse Inc. / IG: @tayethatruth / Paypal: Paypal.me/TayeTheArtist

In Gatesville, Kitchin also said:

“If you are a heathen or savage, go and vote against the amendment and eat and drink and sleep with the negro, but I am sorry for the negro. A white negro is ten thousand times worse than a black one.”

Daily Times (Richmond), July 27, 1900

This was a central part of the white supremacists’ strategy. They aimed to create a climate in North Carolina in which it was shameful for a white man to stand with a black man.

If a white man did persist, whether it be out of friendship, stubbornness or his interpretation of Christ’s call to love one’s neighbor (and plenty of white men fit each of those categories), the white supremacists tried to make sure that he would pay a crippling price.

There was no shortage to what could be done even to a white man: if, say, he was a tenant farmer, he might not get the credit he needed to plant his crops and feed his family until the harvest. He might be evicted from his land. Local landowners might blackball him so that he could not farm at all.

If he was a shopkeeper, his customers might disappear. His suppliers might stop deliveries. Vandals might destroy his property.

No matter how he made his living, his neighbors might scorn him, his church might turn its back on him. He would worry about his wife and children, and he would always have to keep an eye over his shoulder for unseen dangers.

Artwork credit: Nina Oteria / IG: @ninaoteria / Venmo: @NinaOFoster

The “Rapid-fire gun” from Wilmington

The disfranchisement campaign of 1900 shared many of the same leaders and many of the same tactics as the better-known white supremacy campaign that had swept the state in 1898.

As I mentioned earlier, that campaign culminated with the Wilmington massacre and coup d’etat, which occurred in November 1898.

One of the first historians that studied both campaigns in depth, Professor H. Leon Prather, believed that the violence was more widespread and in some ways worse in 1900.

During the 1900 campaign, reminders of the Wilmington massacre were never far away. In speeches, white supremacist leaders often threatened blacks and their white allies by reminding them of Wilmington.

At Charles Aycock’s rallies in Duplin and Roberson counties, for instance, the Red Shirts even paraded with the “rapid-fire gun” with which the Wilmington Light Infantry had gunned down black citizens in Wilmington two years earlier.

In Wilmington, “the rapid-fire gun,” an early version of a machine gun, had been under the command of William Rand Kenan, Sr., in whose name his children gave the funds to build Kenan Memorial Stadium in Chapel Hill.

“The rapid-fire guns which did service at Wilmington during the [massacre] two years ago occupied a conspicuous place in line.”

Richmond Times, July 20 1900

Artwork credit: SpiritHouse Inc., curated by Naeemah Kelly / IG: @naeemahk / CashApp: $naeemahk

You were asking about “Systemic Racism”

The white supremacy movement was extraordinarily successful. On the 2nd of August, the disfranchisement amendment passed by a landslide.

The scale of the violence and electoral fraud in the election has never been fully calculated.

However, an older, but very illuminating study called Maverick Republican in the Old North State: A Political Biography of Daniel L. Russell gives us a telling window into the scale of voter suppression and fraud in the election.

In that book, one of my favorite historians, Jeff Crow, and his mentor at Duke, Professor Robert Durden, cited the example of New Hanover County, where Wilmington is the county seat.

New Hanover County was a majority-black county in 1900. Yet according to Crow and Durden, election returns indicated only two votes against the disfranchisement amendment in the entire county.

Such an outcome was of course not remotely credible in a fair election.

The election’s other results were also far-reaching. Charles Aycock, for one, was elected governor. He would go on to become the single most lauded political figure in North Carolina history.

Overall, the white supremacists gained total control over the state’s political system—the governorship, the legislature and the courts.

They held that power for more than 60 years.

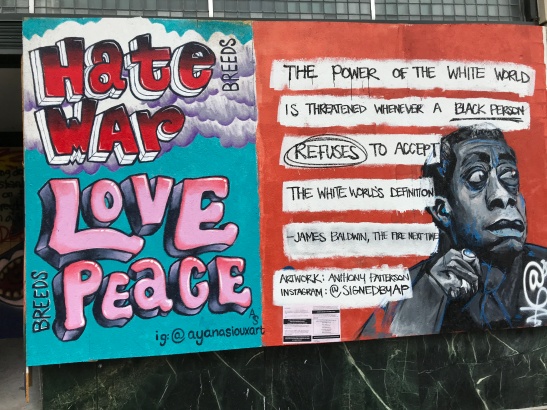

Artwork credit (left side): Ayana Sioux Jarvis / IG: @ayanasiouxart / Paypal: ayanasioux@gmail.com / CashApp: $ayanasioux. Artwork credit (right side): Anthony Patterson / IG: @signedbyap / Paypal: info@aipatterson.com / CashApp: $aipatter

I am not aware of a single white political leader in the state of North Carolina that spoke out publicly against white supremacy in the first half of the 20th century.

Similarly, for more than 50 years, neither major political party ran a statewide candidate that publicly opposed whites-only government.

The disfranchisement amendment of 1900 was not completely undone until 1965, when the civil rights movement succeeded in pushing the U.S. Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Artwork credit: SpiritHouse Inc., curated by Naeemah Kelly / IG: @naeemahk / CashApp: $naeemahk

The consequences of that long period of white rule reached into every corner of our society.

While they were in power, the white supremacists of 1900 and their heirs stitched white supremacy deeply into the fabric of North Carolina‘s institutions.

Voting districts, precinct lines, polling sites and hours, the locations of roads and other infrastructure, public school spending, tax policy, the mental health system, policing methods, judicial and sentencing standards, the penal system, workplace rights, lending and banking practices, health care and social services funding, historic sites and museums and even the locations of sidewalks, parks and shaded streets—white supremacy shaped them all.

For generations, the state’s white leaders acted as if no part of state, county or municipal government was too large or too small to be shaped, first and foremost, by race.

And When it Comes to Elections

After 1900, those same political leaders continued to draw heavily on the electoral tactics with which they had gained power.

Those tactics can be boiled down to three principles: encourage low voter participation overall; go to great lengths to suppress the black vote; and polarize the electorate by enflaming racial divisions and placing divisive “social issues” at the center of campaigns.

“You may talk tariff, revenue, corruption, fraud, pensions and every other evil . . . till doomsday and not one man in ten will remember what you said three minutes after you stop . . .. But you talk negro equality, negro supremacy, negro domination to our people, every man’s blood rises to boiling heat at once.”

W. H. Kitchin, Quoted in Eric Anderson, “William Hodge Kitchin”

Since 1900, both of the state’s major political parties have used that formula repeatedly in order to gain and/or hold onto power.

Artwork credit: Kiara Sanders / IG: @smalldarkandbright / Venmo: @kiara-sand-6 / CashApp: $keksand

Generally speaking, the state’s Democrats did so more prior to 1960, while the state’s Republicans have done so more since 1972.

Of course, like all things, those tactics come with a price: they deepen the rifts among us, revive old prejudices and heighten our darkest fears and our gravest suspicions of one another.

Artwork credit: A.yoni Jeffries / IG: @ayonijeffries / Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/ayonijeffries / PayPal: https://www.paypal.me/awaruhi / CashApp: $AWARUHI / Venmo: @awaruhi

A Final Note

In the weeks since George Floyd’s murder, I have seen the people of North Carolina and those around the nation discussing race and history in a way that I have never seen before.

A vast, generally thoughtful and remarkably well-informed discussion of America’s racial past has arisen in our streets, on social media, in our living rooms and factory floors and just about everywhere else.

I hope my own work has played a useful part in some of those conversations.

Above all, I have been heartened to see so many young people taking leadership in the protests sweeping the country and in the efforts to educate people like me about parts of our past that we never learned in school.

I find their protests very courageous, especially when they know they’re also dealing with a heightened threat of Covid-19 when they’re out there in the streets.

Artwork credit: Durham Mural Crew members: Cailee Parker / IG: @Kuda.4x / Cashapp: $kuda4x / Paypal: Robbyking425@gmail.com and Nyla Hoskins / IG: @fgm.hundo / Venmo: Nyla-Hoskins and Jaiden Holden / IG: @thatdude_jden / CashApp: $thatdudejden / Paypal: paypal.me/thatdudejden

I take it as a sign of the seriousness of their purpose and as a sign of the extent of the crisis over race in America today. I find it very inspiring that they care so much about this country’s future.

It has been a long time since I have felt this optimistic about America’s future, and that is because of them.

To any of those young people who might read this, especially here in North Carolina: if I can ever do anything to support your efforts, I hope you’ll let me know.

What I know is yours. If you call I will come. Where you lead I will follow.

* * *

The murals above were created by Black artists on boarded-up storefronts in downtown Durham, N.C. between June 5 and 17. The artists were paid for their work by business owners and the Durham Artist Relief Fund with organizational support from Art Ain’t Innocent, North Star Church of the Arts and community volunteers. Credit and payment information is included with each image. Please credit the artists if you share the images and continue to directly pay the artists for their work. You can also make a donation to northstardurham.com/artistrelief.

The newspaper quotes above come from the Virginia Chronicle, an on-line collection of historic newspapers maintained by the Library of Virginia in Richmond. I could have used North Carolina newspapers, but the Virginian papers covered the 1900 campaign well and the on-line archive made them very accessible here in the time of Covid-19.

Painful to read but thank you for writing it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, David. 401 years and counting–may this year mark our final turning point. All in.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The history most of us have not been taught. If we were ignorant, now is the time to learn. If we know better, now is the time to act. Lord, have mercy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

120 years later we have MEGA red hats. Somethings never change.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your wonderful writings. I’ve lived in North Carolina most of my life, but my father is military so we travelled around a lot. I felt that I knew history but I truly never knew it at this level. I grew up in Goldsboro after my father retired from the USAF and after reading your post on ‘red shirts’ it saddens me and makes me question why their is still a high school bearing the name of Charles B. Aycock. Again thank you for sharing and I look forward to more of your writings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Mr. King. Means a lot to me to hear from you.

LikeLike

Mr. Cecelski,

Thank you! I am blessed to have came across your passionate and informative article, “Summer of the Red Shirts”. I actually became obsessed with learning about the red shirt concept and researched a tragic day in US history that sadly I had never heard of before I read your article today. The day in question is November 10, 1898 with the ‘Wilmington Massacre. I was brought to tears. I’m sad and angry that I never learned of this before or if I had it never resonated with me as it did today. I’m 54 so I went to school during a time of integration, but at the same time so much was left out of our history books. Interestingly in doing the research today, one of the articles that I came across was in the national publication “The Atlantic” and you were noted in that article as a well-known North Carolina historian. It made me feel very honored to connect with your historical writings. And through gaining a better understanding to history, I’m looking forward to gaining a new perspective and education about our past and how we can move toward a united future. Thank you again for educating me and empowering me.

Don

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for teaching me something else I did not know. I grew up in Warsaw but even in the 50’s no white person ever mentioned the red shirts. (By then the Klan were mostly secretive.) The idea of thousands of people gathering then is astounding.

LikeLiked by 1 person

David,

This post came to my attention in a very round-about way. I marvel at the serendipity that can come from living in one place for a long time!. I learned so much and appreciate the art that accompanies this piece. I’m wondering….Do we hear women’s voices come through during this time in NC history?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Cherie– how sweet to hear from you! Greetings from L and me both! You ask a good question and I wish I had a more encouraging reply for you– by and large, I’m afraid white women stood strong with white supremacy– you’ll see in some of the quotes in my story that white women generally made up a large and vocal part of the white supremacy rallies in 1900. (For black women, of course, it was another story….) Much of the white supremacy campaign was pitched as “protecting white womanhood” from African Americans and the movement’s propaganda often compared black and white political alliances to “racial miscegenation.” Many white women supported that view. I know there must have been white women dissenters, but I think we know very little about them. Then and in the coming years of white supremacist rule in N.C., white progressive women found themselves painted into a corner. Even one of my heroines, Gertrude Weil of Goldsboro, remained silent. She was a remarkable suffragist and campaigner for a host of important issues– prison reform, African American education, labor rights etc. But even Ms. Weil never raised her voice against white supremacy and white rule– not even once. I’m a bit unclear how much that was because of her accepting white supremacist ideas and how much was just a hard-nosed political calculation: she must have known that, if she had protested against white supremacy, she would have been completely marginalized and her other reform efforts would have gone for naught….

LikeLike

David, Because you mentioned her, I have dug in and learned more about Gertrude Weil. Thank you for the steer. I’m heartened that in these days we see white women in great numbers speaking out in protest to police violence and racial injustice. The women I see on the screen are much younger than I am. So, I join your voice in encouraging the many women from different generations who are stepping up to lead the work ahead.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Exodusters and the Burning of the Hackney Carriage Factory | David Cecelski

Pingback: Edenton and the Battle for White Supremacy | David Cecelski