Russell Coles and Teddy Roosevelt with the carcass of a giant oceanic manta ray on Captiva Island, Florida, in 1917. Courtesy, Walter Coles, Sr., Chatham, Va.

This is chapter 10 of Shark Hunter: Russell J. Coles at Cape Lookout.

For many students of American history, the letters between Russell Coles and Teddy Roosevelt would be the most important historical documents that my daughter Vera and I found at Coles Hill.

Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt was of course the 26th president of the United States, having served from 1901 to 1909.

He was a politician, naturalist, conservationist, big-game hunter, explorer and writer. The image of his face appears on Mount Rushmore, next to George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln.

His legacy is complex: Native American activists and other protestors, for example, recently convinced New York City’s leaders to remove his statue at the American Museum of Natural History because of his strong belief in white supremacy and in the right of whites to rule over other races.

Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt, by James Earl Fraser, 1939. The statue stands at the Central Park entrance to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. From Wikicommons

My Fight with the Devilfish

Roosevelt was 58 years old and near the end of his life when he read an account that Russell Coles had written of his expedition to hunt giant manta rays in the Gulf of Mexico. That account was called “My Fight with the Devilfish” and appeared in the American Museum Journal in April 1916. The Journal was published by the American Museum of Natural History and Roosevelt, a longtime supporter of the museum, read the story that fall.

Only two years earlier, Roosevelt had returned half-dead from his legendary journey to the headwaters of the Rio da Duvida, the “River of Doubt,” in the Amazon jungle of Brazil.

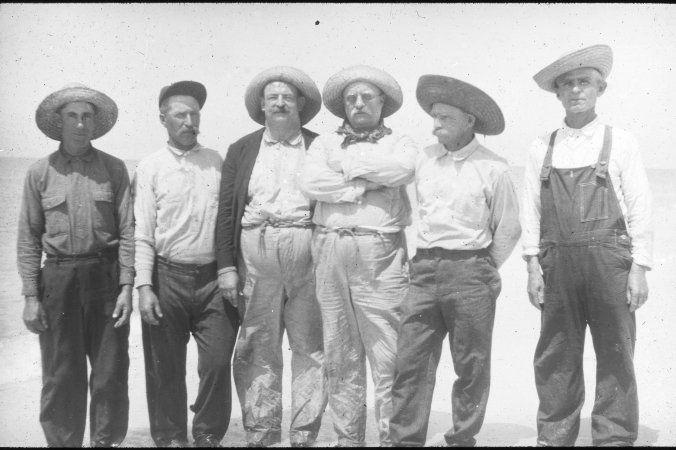

The manta ray hunting crew (left to right): Roland Phillips, Capt. Charlie Willis, Russell Coles, Teddy Roosevelt, Capt. Jack McCann & Mart Lewis. Courtesy, Walter Coles, Sr., Chatham, Va.

On that expedition, he had nearly died from starvation, a wound to his leg and tropical fevers.

Three of his fellow explorers died on that trip. Roosevelt and the rest of the explorers only survived because a group of rubber workers stumbled onto them in the jungle and rescued them.

Roosevelt’s health never fully recovered, but he was undaunted when he read Coles’ sensational account of his adventure in Florida.

He immediately got in touch with Coles, who, at the age of 51, was only a few years younger than Roosevelt. Coles quickly invited the ex-president to join him on a new manta ray hunting expedition.

Only a few weeks later, the two men were engrossed in planning the details of a trip to Punta Gorda, the town on the Gulf Coast of Florida where Coles had hunted giant manta rays twice previously. At the time, Roosevelt was in the midst of a bramble of political issues related to the First World War, but he seems to have been unable to think about anything but the prospect of killing a giant manta ray– or, as he called it, “a devil-fish.”

In one of the letters that Vera and I read at Coles Hill, dated Feb. 17, 1917, Roosevelt wrote Coles:

“The one thing I most desire to do is to harpoon a devil-fish, and I am pleased down to the ground, that everything is to be subordinated to that one consideration—until I get my harpoon into one.”

The two men were made for one another.

At the time, Roosevelt was still a leading candidate to be the Republican Party’s presidential nominee in 1920 (for what would have been his third term). But in a letter dated Jan. 11, 1917, Coles assured Barton Bean at the Smithsonian that he and Roosevelt would put aside political ambitions and social niceties while they were in their camp on Captiva Island.

By that, he meant that they would not entertain any of Florida’s elected officials or influential political donors while they were in Florida.

“Col. Roosevelt, my crew and myself will live very roughly in camp and have no visitors, in order that entire 3 weeks may be devoted to savage bloody fighting.”

The Cape Lookout Life-Saving Station

The relationship between Roosevelt and Coles had actually started eight years earlier, in the summer of 1908.

Left to right: Russell Coles, Teddy Roosevelt, Mart Lewis and Roland Phillips. Captiva Island, Fl., 1917. Courtesy, Walter Coles, Sr., Coles Hill, Va.

Roosevelt related the story in an account of his and Coles’ manta ray hunting expedition that he later wrote for Scribner’s Magazine.

In that story, he wrote:

Built in 1916, the Cape Lookout Coast Guard Station still stands today. It was in operation until 1982. Photo by Jarek Tuszyński

“At the end of July, 1908, Mr. Russell Jordan Coles . . . was at Cape Lookout, North Carolina. A heavy gale blew up and several vessels were partly wrecked. The life-saving crew of the Cape Lookout Station, though hampered by antiquated and outworn equipment, did everything possible to save them.

However, despite their gallantry and efforts, one of the vessels—the John Swann—would have been abandoned and have become a wreck had not Coles been in the harbor.

“He was aboard his hired boat and he called for volunteers and put out to the rescue. The captain and owner of the boat, Charles Willis, and five other men accompanied him. They were able to rescue the vessel after a very exhausting and dangerous struggle.”

Soon after the rescue of the John Swann, Coles wrote to then-Pres. Roosevelt and made a plea for new and better equipment for the life-saving station at Cape Lookout, where, for 25 years, he spent his summers on a houseboat. Somehow his letter caught the president’s attention. A couple months later, according to Roosevelt, the island’s lifesaving crew received the aide it needed.

When Roosevelt first read Coles’ article about hunting giant manta rays, he didn’t realize that Coles was the same individual who had sought his help for the Cape Lookout station in 1908. Coles, however, certainly remembered that earlier episode when Roosevelt wrote to him in 1916.

Roosevelt and Coles immediately began making plans for a three-week expedition to Florida.

Though eager to join Coles, Roosevelt found it difficult to extract himself from the white-hot political debates that were going on related to U.S. policy with respect to the First World War.

At that time, German submarine attacks on U.S. shipping had sparked a fierce debate within the U.S. Congress over the country’s involvement in the war.

While Roosevelt worked to get free of his political responsibilities, Coles organized the logistics of the trip. He arranged for Capt. Charlie Willis and the rest of his usual crew from the North Carolina coast to make the journey to Florida.

He also lined up Capt. Jack McCann, the legendary fisherman in Punta Gorda that we met in chapter eight of our story, to be their local guide again.

The manta ray hunters’ camp in waters just off Captiva Island, Fl., 1917. Courtesy, Walter Coles, Sr., Chatham, Va.

Coles and his crew of course felt it an honor to be hosting the ex-president. They felt a special sense of obligation both to keep Roosevelt from harm and to make sure that he satisfied his ambition of harpooning a giant manta ray.

In the end, because Roosevelt did not think that he should be away from Washington, DC longer than necessary when Congress was in session, they settled on a shorter expedition than they had originally planned. Roosevelt, Coles and his crew would be in camp on Captiva Island for only a week.

During those months of planning, Roosevelt and Coles also began to get to know one another better. In their correspondence, Vera and I could tell that they each felt as if they had discovered a kindred spirit.

By November 18, 1916, Coles was confiding to Roosevelt that he hoped to write a book titled Dangerous Game of the Sea. He acknowledged, however, that he had doubts about his ability to write the book, given his inexperience as a writer and the demands of his tobacco business.

Over the winter their correspondence grew more intimate. At some point, probably before Christmas, Coles was also a guest at Sagamore Hill, Roosevelt’s home near Oyster Bay, a community on Long Island, New York.

A few weeks later, on February 7, 1917, Roosevelt wrote Coles to reassure him that he was fit enough to endure a week of living in a rough camp for a week when they were in Florida.

“I have no longer any physical prowess, but I am not a mere softy, to mind little trivial hardships,” Roosevelt (sort of) reassured him.

Roosevelt and Coles posing with their harpoons. Behind them (left to right) are Roland Phillips, Mart Lewis, Capt. Charlie Willis & Capt. Jack McCann. Photo courtesy, Walter Coles, Sr., Chatham, Va.

In the following weeks, they began dreaming of even bigger adventures.

A few weeks before departing for Florida, Roosevelt and Coles even discussed the possibility of raising a company of soldiers made up of men such as themselves (“aging, overweight, white upper-class man-children?” one of my friends asked me) to go to Europe and fight in the First World War.

For Roosevelt the idea was more than a dream. In a meeting with President Woodrow Wilson, he actually proposed the idea of his leading a new iteration of the “Rough Riders” into war. He also sought to build support for the idea in the U.S. Congress, and he encouraged his supporters to join him in battle. At one point, he was receiving as many as 2,000 offers of enlistment a day.

It all went for naught. Wilson, who was not fond of Roosevelt, privately considered the new version of the Rough Riders to be a publicity stunt meant to further Roosevelt’s political ambitions. In public, however, the president expressed his appreciation for Roosevelt’s patriotism, but he did not take up his offer to go war.

Roosevelt did sacrifice a great deal during the war, however. All four of his sons enlisted in the military and went to the front lines. Two were wounded in battle. Another, Quentin, a pilot, died when his plant was shot down in July 1918.

Roosevelt’s last great adventure, it would turn out, was not destined to be on the battlegrounds of France, but in the Gulf of Mexico, hunting giant manta rays with Russell Coles.

I’ll continue that story next time.

-To be continued-

Great history! Cape Lookout was my last job in the Coast Guard= Up date the station & replace generator in light house= we updated all off shore units (automated) & take all personal off. Frying Pan, Chesapeake, Diamond light= I retired in 12, 09, 1982 @ 31 years. Great life! I am 88 now= sure enjoy your

Sent from my iPa

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mr. Webb, I would sure always welcome more of your memories of those days!

LikeLike

Interesting read and tale. I now live in Beaufort, NC and grew up here. I remember seeing a very large black manta ray jump completely out of the water and splash back down in the water along Front Street. I and the rest of the guys there, we’re stunned and left the water immediately. This strip of water is called Taylor’s Creek and becomes an outlet to the ocean. I thought at the time it was a manta ray having recently seen one in a movie. This was right in the middle of town in front of the post office and the Inlet Inn hotel dock. About 1954. I wondered where it came from and after reading your article I realized it was from the gulf which swings very close to the coast of North Carolina.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome sight– I would love to see it! That’s the kind of thing you don’t forget.

LikeLike

was his statue damaged during == protest BLM ?? Horace

Sent from my iPa

LikeLike

No, the protests were peaceful. I don’t know that much about them, but I know they included an “alternative tour” of the museum from a Native American perspective.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Mullet Fishermen of Punta Gorda | David Cecelski