KKK members burning a cross in Greenville, N.C., 30 miles north of the Cool Springs FWB Church, Oct. 18-19, 1965. From The Daily Reflector Image Collection, ECU Digital Collections

On the day after the Klan blew up their church, the members of the Cool Springs Free Will Baptist Church in Ernul, N.C., gathered in the churchyard for worship. The date was April 10, 1966. It was Easter morning.

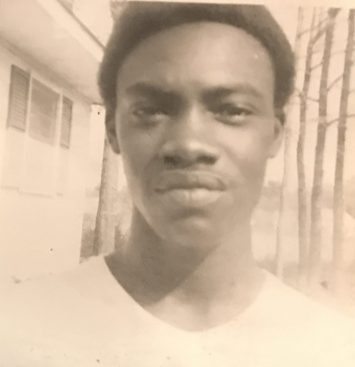

The tiny hamlet was located among the tobacco fields and swamplands of eastern North Carolina. Chris Johnson, who was 13 years old at the time, remembers the day well. A retired army sergeant who now resides in San Antonio, Texas, Mr. Johnson grew up in Ernul and his family has deep roots at Cool Springs. Generations of his family have worshiped there.

Mr. Johnson got in touch with me last summer after he read an article that I wrote years ago on the history of the Ku Klux Klan in eastern North Carolina. In that article, I had mentioned the church bombing.

Sgt. First Class Chris Johnson of Ernul, N.C. during his service in the U.S. Army. Courtesy, Chris Johnson

I was glad to hear from him. I knew that the Ku Klux Klan had bombed the church, but little else. I knew none of the details. No other historian or journalist had ever told the story either, and I had never met anyone from Ernul that could tell me more about that night in 1966.

In today’s post, I’d like share some of what I have learned from Mr. Johnson. I will rely mostly on his memory to tell the story, but I have done some background research that I will share here, too. I found the most important background material at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Archives & Rare Book Library at Emory University in Atlanta.

* * *

When we talked on the phone, Chris Johnson told me that you could hear the sound of the bomb going off for miles on that Holy Saturday night in 1966. An AP report agreed with him: it said people seven miles away heard the explosion. For the families that lived near the church, the blast was deafening and shook their homes.

Mr. Johnson does not remember how he and his mother, father and four brothers reacted to the explosion that night. Loving parents perform miracles for their children and perhaps his mother and father managed to conceal what had happened until the next day. Perhaps his mother even managed to soothe him and his brothers back to sleep.

But while his children slept, Mr. Johnson’s father went out into the night to see what happened. His father, Felbert “Teen” Johnson, was a modest man, he told me, and one of high principles. “A hard man, but a good man,” he said.

Teen Johnson was a lay carpenter and laborer and jack-of-all trades. Mr. Johnson told me that he had left school after the third grade and had gone to work to help provide for his family.

Mr. Johnson remembered his father as a perfectionist in all he did to make a living, whether it was building boats, doing carpentry and masonry work or planting trees and cutting timber for logging companies. He also helped his wife to raise their children to be the best they could be. He taught them, his son told me, “to be respectful of people.”

That night his father could only have expected the worse when he heard the explosion. Because of Ku Klux Klan terrorism, he had been sleeping with a shotgun and rifle next to him for some time.

They were trying times. Mr. Johnson recalled nights when his father made the six of them sleep together in one room of the house because he was worried that the Klan might attack their home.

* * *

Cool Springs was just an old country church, he told me. It was a plain white wooden frame building: one big room, the altar and choir loft upfront, pews reaching to the front door, stain glass windows.

Mr. Johnson described the Rev. R. E. Worrell, the church’s long-time pastor, as a slight, gray-haired man with a mustache. He lived in Belhaven, a town 50 miles distant, but he drove down to Ernul for worship services. He was an exhorter of the old school, the kind that people sometimes call a “fire and brimstone preacher.”

His congregation was typical of that part of eastern North Carolina in those days. According to Mr. Johnson, the church’s members included tenant farmers and field workers, maids and nannies and washerwomen, lumber mill workers, school bus drivers, teachers, nurses and oyster shuckers.

Mr. Johnson has a thousand memories of Cool Springs when he was a child. He remembers the old-fashioned dinners on the grounds, and he recalls his grandmother telling Bible stories in the back of the church, where she taught the children’s Sunday school class.

He had grown up in the church. Rev. Worrell had baptized him in a local river. He had gone to weddings, funerals and homecomings there. The church’s members had all felt God’s love there. Cool Springs was the bedrock of their lives.

* * *

On that night before Easter in 1966, Teen Johnson arrived at the church and found it in ruins. “Blown to bits pretty much,” Mr. Johnson told me: piles of planks everywhere, shards of pews scattered here and yon, the front wall of the church demolished.

He could not have been too surprised. Only five months earlier, Klansmen had bombed one of the congregation’s sister churches, St. Joseph’s Free Will Baptist. “Saint Joe’s,” as it was known, was in Vanceboro, a small town six miles north of Ernul.

There had been other bombings, too. The previous year, Klansmen that lived a few miles from his community had set off three bombs in New Bern, the county seat, 15 miles south of Ernul.

Two of the bombs exploded outside of a civil rights meeting at St. Peter A.M.E. Zion Church. The other damaged a funeral home owned by a local NAACP leader.

According to internal government files that I found at the State Archives Annex in Raleigh, N.C. when I was writing my book Along Freedom Road, law enforcement leaders also suspected that Klansmen from that vicinity were responsible for at least two other attacks that same year elsewhere in eastern North Carolina.

The first was the bombing of Georgetown High School, a highly respected African American school in Jacksonville, N.C., on the school’s graduation day in 1965. If the bombs had ignited later in the day, hundreds of people could have been killed or wounded.

Coach Tyrone Willingham, shown here with his Notre Dame team in 2004, was a 5th grader in Jacksonville, N.C., when bombs destroyed the Georgetown High School in 1965. He often talks about the incident when he describes his youth and the adversities that he had to overcome. Photo by Sandra Dukes/Getty Images

The second was an attempt to burn down Freedom House, a center for civil rights activists in the town of Plymouth, 50 miles north of Ernul. That occurred on August 28, 1965. At the same time, Klansmen had also sprayed the building with bullets.

* * *

A 13-year-old boy might not have known about some of those incidents, but Mr. Johnson’s mother and father certainly did. There were many others, too, and some of them even closer to home.

In the fall of 1965, when the racial integration of the local public schools began, Klansmen went on a rampage. They shot into homes, blew up mailboxes, burned crosses in yards and torched barns, sheds and other outbuildings.

When I spoke with Mr. Johnson, he recalled the Klan burning a cross in a field just down the road from his home. It was a strange feeling, he told me: his family had often picked crops for the white farmer who gave the Klan permission to burn the cross in his field.

Klansmen burning a cross in the daylight in Pitt County, N.C., not far from Ernul, in March 1966, a month before the bombing of the Cool Springs FWB Church. From The Daily Reflector Image Collection, ECU Digital Collections

As he got older and began going to school with white children, Mr. Johnson got the impression that most of his white schoolmates had some family connection to the Ku Klux Klan. “Almost everybody I went to school with who was white was Klan or their parents were or their grandparents were,” he recalled. And he added, “We fought every day.”

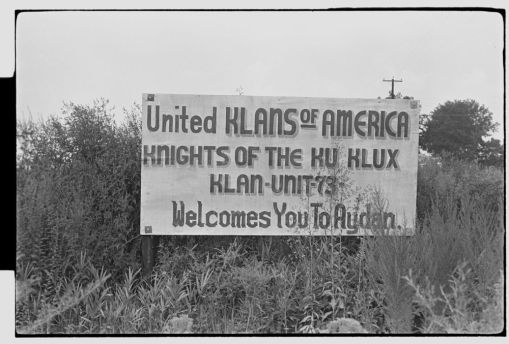

Klu Klux Klan sign on road into Ayden, N.C., 25 miles from Ernul, Aug. 29-30, 1966. From The Daily Reflector Image Collection, ECU Digital Collections

School desegregation was often the source of the Klan’s ire. During the 1965-66 school year, small numbers of local black students began to enroll at previously all-white schools for the first time.

In response, local Klansmen targeted virtually every black family that sent a child to a previously all-white school. They also targeted black teachers that agreed to teach at previously all-white schools and white teachers that agreed to teach at previously all-black schools.

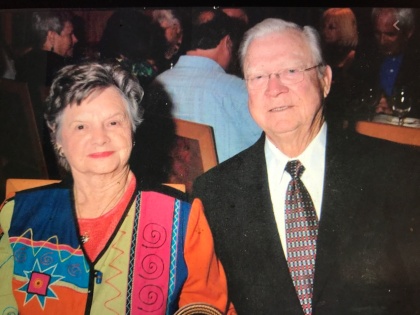

The local KKK also targeted Royce Jordan (here with his wife Janice in 2012) and other whites that supported African American civil rights. An ex-KKKer testified to the U.S. Congress that the Klan had tried to whip Jordan for supporting job training programs for black workers. In Blood Done Sign my Name, Tim Tyson notes that Klansmen also burned Jordan’s barns. At the time, Jordan was mayor of Vanceboro. Photo courtesy, New Bern Sun Journal

The Klan did not stop there. In Vanceboro, Klansmen shot into the home of a 15-year-old black girl because she rode a school bus with white children. On another occasion, Klansmen threatened a special needs child, a white boy, for playing with black friends.

Like other African American children in the area, Mr. Johnson learned young never to leave home alone.

* * *

I grew up in Craven County, N.C., which is where Ernul is. I was five years old and living 30 miles to the south of Ernul when the Klan blew up the Cool Springs FWB Church.

If somebody had blown up my family’s church, I am pretty sure that my father and mother would have expected a prompt investigation of the incident. I think they would have held high hopes for justice.

When Chris Johnson’s father stood in the charred remains of the Cool Springs FWB Church, he could not have had that feeling. He had to take for granted that he and the other members of the church would have to rely on their faith and one another for help, but not the police or the courts.

Neither local, state or federal law enforcement agencies ever arrested Ku Klux Klansmen for any of the many acts of vandalism, arson and assault in the Ernul-Vanceboro area.

To the south, in New Bern, authorities did arrest the three Klansmen that set off the bombs there in 1965. Their names were Raymond Mills, Laurie Fillingame and Edward Fillingame. They all lived in Vanceboro and one was the “Exalted Cyclops” of one of the local KKK branches.

Their fate hardly instilled hope in the justice system if you were African American, however: when the three men pled guilty, a state superior court judge merely sentenced them to probation. They served no jail time for what amounted to attempted murder.

* * *

This is a brief historical aside that I hope provides a fuller sense of the justice system in eastern North Carolina at that time:

In contrast to the probationary sentence for the three Klan bombers, a state judge treated a group of African American teenagers very differently three years later when they attempted to burn down a Ku Klux Klan building in another part of eastern North Carolina.

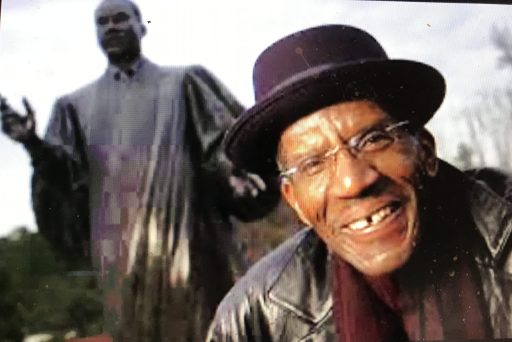

I interviewed Fred Lockamy for a story I called “Sorrow Valley” 15 years ago. Lockamy was one of the four teenagers who attempted to burn down the KKK’s meeting hall in Benson, N.C., in 1968. Photo by Chris Seward. Courtesy, The News & Observer

In the spring of 1968, four youths in Benson, N.C., lost their tempers when they saw a KKK parade celebrating the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Outraged at what they saw, they attempted to burn down the Klan’s local meeting hall. They were not successful. They only charred the bottom of the building’s front door.

None of the boys had any prior offenses. Nonetheless, a state court judge sentenced each of them to 12 years of hard labor.

To learn more about the incident, I recommend an excellent article by one of my former Duke students, Crystal Sanders, in the August 2013 issue of The Journal of Southern History. Crystal is now a professor at Penn State University.

* * *

Now to return to the bombing of the Cool Springs FWB Church in Ernul, N.C.:

Late in 1965, an incident just north of Ernul, on the outskirts of Vanceboro, drove home even more forcibly local law enforcement’s sympathy for the Ku Klux Klan and failure to protect the African American community.

The incident unfolded beginning around 4 AM on September 28, 1965. At that time, an unknown white person or persons fired shots into an African American family’s home.

A large group of the family’s neighbors quickly gathered to find out what had happened and to protect the family from further danger if necessary. Some came armed with shotguns, knives and sticks.

According to an incident report in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) Papers at Emory University, state troopers showed little interest in the white assault on the black family’s home.

However, the troopers arrested 22 of the African Americans who had gathered there to protect the family. They included at least one woman and two children.

According to the SCLC report, which was made by an African American minister who was an SCLC leader in New Bern, authorities released the two children but charged the 20 adults with “malicious rioting,” unlawful assembly and “intent to intimidate the community.”

No Klansmen were ever charged with similar crimes in Craven County or anywhere else that I know of in eastern North Carolina.

* * *

I asked Mr. Johnson if he knew why the Klan had targeted the Cool Springs FWB Church. He was not sure, but he told me that “those white people were taught to hate black people and considered us as inferior.” They seemed to have a special resentment of the church and its members.

A young Chris Johnson, Ernul, N.C., ca. 1966. Courtesy, Chris Johnson

He suspected that the Klansmen also sought to intimidate African American community members in general by targeting one of the places that was most dear to them.

The world was changing. By 1966, African Americans in New Bern had been staging lunch counter sit-ins, economic boycotts and other civil rights protests for more than five years.

The county’s schools were beginning to desegregate as well. Even in Vanceboro, with its two-block downtown, civil rights protests had begun.

The previous fall, for instance, 250 local blacks had held a civil rights meeting at St. Peter’s, a FWB church on Hwy. 43 just north of Vanceboro. At that gathering, they had organized a boycott of the town’s businesses with three goals: fair employment practices, the hiring of a black policeman and voter registration reforms.

These were signs of a new age in that land of sharecroppers and tenant farmers, tobacco and Jim Crow.

“They wanted to destroy what we were attempting to accomplish,” Mr. Johnson told me, referring to the Klansmen that bombed his family’s church. “They wanted to do something to destroy our reality.”

* * *

Chris Johnson can only imagine what thoughts went through his father’s mind that night when he saw the still smoking embers of the dynamite blast at the Cool Springs FWB Church.

He might not know his father’s thoughts, but he does know what his father and the rest of the church’s congregation did when they woke up the next morning: it was, after all, Easter Day, a time for new beginnings and a time for hope. They put on their Sunday best and headed to church.

In the coming weeks, Mr. Johnson’s father and another member of the congregation, Dennis Moore, would lead the church’s re-building effort. They did not look for outside help. They used their own hands and the people gave out of their own pockets.

But that Easter morning, standing in the churchyard, young Chris Johnson and his family and the rest of the worshipers gathered, young and old, and put their weariness of men’s wickedness aside. They lifted their voices in song and prayer, rejoicing in the Resurrection and praying for souls lost in darkness, that they might yet find a path into the light.

It still blows me away how such incidents were happening when I was a child in NC, and how unaware of them I was at the time.

Thank you for bringing these stories to light.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi David, thanks for this chapter. When you were little did you know about violence and the legal response in the communities around you? It’s still, even today, jarring for me to learn these terrible events. But important. I’m glad you and mr Johnson talked – what an experience. Thank you so much for sharing so much with us. Love to you and Laura, and have a good if atypical Thanksgiving celebration Lanier

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Lanier. No, I guess I was completely in my own little bubble growing up– I wasn’t aware of any of the stories that I wrote about in this story. This morning I’m being flooded by messages from other people from that part of the state that feel the same way– though by now, at my age, having excavated this history for longer than I might want to admit, I’m not as shocked when I learn about stories like this one as they are– I guess I’ve gotten used to it. The thing is, to me shock is a good thing in this case– I find knowing the past — the real past including some real dark palces– liberating and freeing– a way of understanding the world we’re in better, but also a way of freeing us from the past so that we can make a better future for our children and grandchildren…. And in some cases, I think that starts with shock. Right?

LikeLike

I should also say: I think we have a lot to thank Sgt. Johnson for: because of him we know this story.

LikeLike

This blog post breaks my heart. I’m Chris Johnson’s age, but I grew up white in piedmont North Carolina. It has only been in the last several years that I’ve come to grips with my white privilege and what a different world people of color have grown up in opposed to my world. Thank you for sharing this story online. I’ll look for your book.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I love your blog and really appreciate the stories you share. You make it personal and real. I am the history chair at St Thomas episcopal church in Bath. I wonder if you have any insight or info into Bath specifically. I can assume that we had KKK, maybe even as members of our church because we are right in the middle of the area you talk about. Our history is pretty well written in the 18th century but the 19th and 20th centuries are less well known. We think a hurricane blew the roof off in the 1800’s and that was where a lot of records were stored. If you can share info with me I’d be so grateful. Also if you could suggest where I should research I would try to fill in some gaps myself. Thank you, patti phelps

Frank or Patti Phelps

>

LikeLike

Thanks so much for your note. What a beautiful church you worship at– I’ve always enjoyed my visits there. I wish I knew more about the civil rights movement and/or the KKK in Bath, but I know very, very little. I haven’t revisited the KKK research I did on that part of the NC coast for a long time, but I remember there were KKK rallies outside of Bath and I remember there was a KKK branch in Belhaven– their meeting place was directly across from city hall and the police station. Jud Mayfield, who as you may know was an Episcopal priest in Belhaven and at an African American church north of Bath (and retired in Bath), was an old friend of mine. Jud used to tell me stories that his older parishioners told him about local race issues and the region’s history– I was very young then and I wish I had listened better and written them down…. This is probably more than you’re asking, but to me uncovering the unwritten stories of our past often starts just by building personal relationships and listening to stories…. With every story we get closer to our real history. I’ll keep Bath on my mind and as I think of good sources for you, I’ll be sure to send them your way.

LikeLike

As a family researcher, it still surprises me when I come across articles like this one. I grew up in Greenville NC and was in Norfolk around this time. Although I knew about some threats bombings, I never heard about this incident. Reading the history that you share helps me with my research and understanding of things that occurred around me. I am African American.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for your note. I appreciate it more than you can know. I’m glad to know that my work is sometimes useful to you, even if sometimes hard to hear. I guess I feel that way, too: stories like this one are hard to write sometimes, esp about a place where I grew up and love so much.

LikeLike

I once thought lynchings had almost completely ended. Thanks to pieces like this–and to witnesses who speak out–I’ve come to see that in many cases they only morphed into bombings. I guess bombings were easier for perpetrators to stomach.

Thank you, David, for pointing out the failings of law enforcement. I’ve read other examples in “Life Of A Klansman” and “Wilmington’s Lie”, etc., too many examples to say there’s no pattern and lots of reason to be sure we know our history today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this blog. I also am looking forward to your book. I grew up in Craven County just a few miles from Cool Springs and the Vanceboro area. In 1965 I was 7 years old. Old enough to remember this things, but too young to really pay attention. I vaguely remember my parents talking about the “black church” at Cool Springs burning down. They told me someone was mad with those folks and had set fire to it. Nothing else was ever said. I just asked my 94 year old Mom about it and she said, yes she remembered the Clan had bombed it, but that was all she know or could remember. Wow, the innocence of youth (on both sides of the racial divide). It makes me sad to know this was so very close to my home/community. We can only look forward to positive progression even though it takes time. Thanks again for your excellent story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Superb and poignant truths from your always rigorous research David and exemplary first hand accounts. A huge “thank you” to Sgt. Chris Johnson for reliving a cruel time in the hope of bettering people and the world today. I do not know you, but as a father I sense your father would be proud, Sgt. Johnson. This entire entry reminds me of the old medical phrase from Osler, “The eyes cannot see what the mind does not know.” Thanks to you all for enriching society’s knowing.

(And I hope you are enjoying some jam with the cooler weather, David:) LW

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just discovered your writings about the bombing of Cool Springs Free Will Baptist Church in Ernul,N.C.

I am a retired state trooper, who was stationed in Vanceboro,N.C. in 1965 to1971. I was on duty the night the church was bombed. In fact I was in front of the church when the bomb exploded .Fortunate for me I was inside my patrol car at the time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much for writing, Sir. I would very much like to hear more about your experience if you’re up for it. Can I call you sometime? For privacy’s sake, perhaps you should reply to my email address: david.s.cecelski@gmail.com. Thank you again for writing.

LikeLike

Pingback: Remembering a Church Bombing: A Conversation with Retired State Trooper Bob Edwards | David Cecelski

Pingback: Our Coast: Remembering a Church Bombing - OBXNews.Live

Pingback: In the Small Town Where I Grew Up | David Cecelski

Pingback: Memories of Plymouth: One of the State’s Leading Criminal Justice Advocates Goes Home | David Cecelski