This talk was written for “Reckoning with Racial Terror: Slavery, the Death Penalty and Mass Incarceration,” a virtual symposium sponsored by the North Carolina Commission on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Justice System,” February 5, 2021.

Today I want to talk about slavery, convict labor and the construction of the old Central Prison in Raleigh, N.C. These are weighty subjects and I only have time to touch on them briefly today, but I hope that I can at least contribute a few worthwhile thoughts to this extraordinary gathering of scholars, activists and other concerned citizens.

The story that I’m going to tell today comes from unpublished historical research that I did nearly 40 years ago, when I was investigating a hunger strike at the old Central Prison.

That hunger strike began on J-Block, a solitary confinement unit, on November 8, 1982. As some of you may remember, the entire prison had grown incredibly decrepit by that time. The great stone walls were literally crumbling, and the city had already condemned parts of the main building. The whole prison would soon be demolished.

But J-Block was the worst. Inside the prison, J-Block was called “The Hole.” It was 22 damp, dimly lit, 6 x 8-foot cells where the toilet water often froze on cold nights. A legal aid attorney described it to me as “the worst block in one of the country’s worst prisons.” Some inmates remained in The Hole for years.

Central Prison ca. 1950s-60s. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

On the first or second day of the hunger strike, a Death Row inmate named Larry Darnell Williams (who was not on J-Block) wrote to me and asked if I would help to spread word of the protest and the hunger strikers’ grievances beyond the prison walls.

That was the beginning of my research on Central Prison. At first, I just focused on the hunger strike’s details: I corresponded with all 14 of the hunger strikers, visited six or seven of them, spoke with prisoner rights advocates who knew J-Block and obtained a variety of internal prison records related to the hunger strike.

But then I wanted to understand more about the historical forces that created J-Block and the rest of Central Prison. That led me into the State Archives, where the historical records of state agencies, including the prison system, are kept. Today I would like to share for the first time what I discovered there.

In case you are interested in learning more about the hunger strike, I have included an excerpt of a longer piece that I am writing about it at the bottom of this page.

Today, though, I want to go further back into the past. I want to look at the construction of Central Prison and at the rise of a kind of convict labor grounded in the Age of Slavery.

* * *

At the State Archives, I learned that the North Carolina General Assembly first considered a bill for the construction of a state penitentiary in 1791. That was of course only a few years after the American Revolution. At the time, proponents of building a penitentiary actually found their inspiration in humanitarian values that we usually associate with the Age of Enlightenment.

As a member of the State House argued during a debate a decade later, in 1801, the idea of a penitentiary was “founded on the natural rights of mankind, and consistent with the social compact in civilized society.”

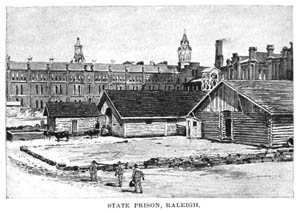

Central Prison ca. 1900. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Seen as an alternative to the brutal corporal punishments of that day and the squalid conditions in the state’s county jails, a penitentiary was actually considered what we would call a progressive reform today.

Not surprisingly then, the state legislature of 1868-69 that finally authorized the construction of the North Carolina State Penitentiary (later called Central Prison) was the most progressive in the state’s history up to that point. For the first time, African Americans served in the legislature, for one thing. They included the brilliant slave rebel and abolitionist Abraham Galloway, who was the subject of my book The Fire of Freedom: Abraham Galloway and the Slave’s Civil War.

Even then, though, the legislative bill authorizing the prison’s construction ominously declared that a statewide penitentiary was of “interest to every taxpayer in these times of general distrust, disquiet, and financial distress:” code words, we would call them today, for white fear of black freedom and white supremacy’s downfall.

In those first years after the Civil War, a relentless war was being waged on African American freedom. It was fought on many different fronts. Those were the years that Abraham Galloway led a black militia fighting the Ku Klux Klan in Wilmington, and they were also the years that white authorities rounded up hundreds and possibly even thousands of ex-slaves, charged them with crimes on the flimsiest of pretexts and flogged them in town squares so that, under state statutes, they would lose the right to vote.

At the State Archives, I learned that Central Prison’s first inmates built the penitentiary from the ground up. They dug the stone in a granite quarry on the grounds, cut the stone into massive blocks and dragged them to an old farm on what was then the edge of Raleigh. In great earthen kilns, they baked the bricks that eventually walled them in and forged the iron bars and doors that caged them.

Early depiction of Central Prison (State Prison), Raleigh, N.C. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

As they went about their work, they used the language of slavery: they referred to the prison grounds as “the plantation.” They ate “rations.” They lived in “The Quarters.” They called their overseers “master.” Often, as we will see in a second, they were “hired out.”

They started construction with their own cells and worked to the outer walls. While building the penitentiary, they lived in the building’s hollow shell, separated from the outside world only by a rather unimposing wooden stockade. The construction lasted 15 years.

Records at the State Archives indicate that the prison grounds were unsanitary, overcrowded, infested and cold. By 1871, only a year after construction began, a quarter of the convicts suffered from scurvy. Both typhoid and yellow fever swept through the prison grounds that summer.

Three years later, Central Prison had the highest mortality rate among its inmates of any penitentiary in the United States, twice as high as any other. The prison physician, a Dr. Hill, lamented “this great amount of sickness and suffering.” He blamed “the characteristic improvidence, recklessness, and disregard for sanitary regulations which prevail among the refuse colored population.”

Enlightenment ideals aside, race was the crux of the prison’s justification from the start. Eighty percent of the convicts were African American. Most had formerly been enslaved on plantations in eastern North Carolina. We have no way to know if they committed crimes that we would recognize as such today: at that time, eastern North Carolina was the scene of a guerrilla war between those who clung to white supremacy and those, black and white, who did not.

Under those circumstances, race could not have been embedded any more deeply into notions of crime and punishment. In the eyes of the white supremacists, an African American who refused to defer to white authority in any way was by definition a criminal. African Americans often ended up on a chain gang for a decade or more for the slightest violations of the racial code of the time, haphazardly labeled vagrancy, loitering or petty theft.

The prison physician, Dr. Hill, referred to the prison’s African American inmates as “refuse.” The prison’s construction supervisor had a different view. He saw abilities in those former slaves that impressed him deeply. In letters and official reports, he boasted of the large number of highly skilled masons, stonecutters, blacksmiths and other master builders among the ex-slaves and, of course, at his disposal.

A significant, but uncertain number of Central Prison’s first inmates perished from malnutrition, exhaustion and disease while they built the prison. In 1871, reports of hungry prisoners eating cats circulated in Raleigh. At a state government hearing on conditions inside Central Prison, eyewitnesses alleged that guards and prison officials had forced women prisoners into prostitution, again a feature of prison life that resonated with slavery.

Methods of discipline and punishment within the prison also drew heavily on slavery. A female inmate named Rhody Foster, for instance, died after being gagged and tied to a post in 1872.

The superintendent of Central Prison also leased inmates to railroad construction and canal-digging projects across the state. This, too, mimicked slavery. Prior to the Civil War, slaveholders often “hired out” enslaved men and women to other individuals, usually for a year at a time, as well as to private companies and public works projects. Those Central Prison inmates who were “hired out” had even higher mortality rates than those that remained on the penitentiary grounds.

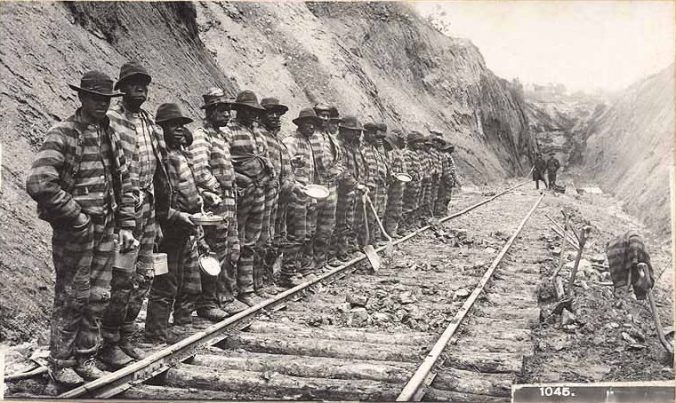

Convict railroad builders, NC mountains, ca. 1900. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Central Prison convicts who built many of the first railroads in the Appalachian Mountains seem to have had the worst time of it. Their labors involved blasting tunnels, scaling ridges and bridging rivers. In a three-year period, at least 10 Central Prison convicts leased to the Western North Carolina Railroad died in accidents. Another 22 died of pneumonia and 17 more succumbed to tuberculosis.

Other Central Prison inmates constructed state government buildings, including the Governor’s Mansion, the Supreme Court building, public hospitals and asylums. Their labor helped to finance the construction of Central Prison, but often slowed the work to a crawl. The prison’s construction supervisor complained especially that he could not find adequate labor because of the high number of inmates leased to the railroads.

As Mathew J. Mancini writes in his book, One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866–1928, “North Carolina’s nineteenth-century rail network was largely an achievement of convict labor.”

At Central Prison things grew grimmer, if that was possible, as the prison neared completion. The prison’s colossal outer walls were 20 feet high and 17 feet thick, and as they rose around them the inmates began to panic. At some points, they held work stoppages. At other times, they sabotaged construction. A few made reckless, suicidal attempts to escape in broad daylight. According to the prison superintendent, they could not bear the thought of having the walls shut them off so entirely from the outside world.

* * *

As those last granite stones were laid in place, the dye was cast. In the coming decades, more prison walls would go up. Convict labor would remain at the heart of the state’s penal system, and inmates of color would continue to bear the brunt of working conditions that were little different than slavery.

In North Carolina’s use of convict labor, we can also see a principle that may be prevalent in all capitalist societies: a conviction, at least among the upper classes, of the virtues of hard labor for reforming the character and even healing the bodies and souls of the poor and working classes, and most especially people of color.

During the Industrial Era, you could find that principle applied in penitentiaries, poorhouses, debtors’ prisons and insane asylums throughout America and Great Britain. Similarly, slaveholders in the antebellum South often argued that the harshest kinds of slave labor were a positive good for black people.

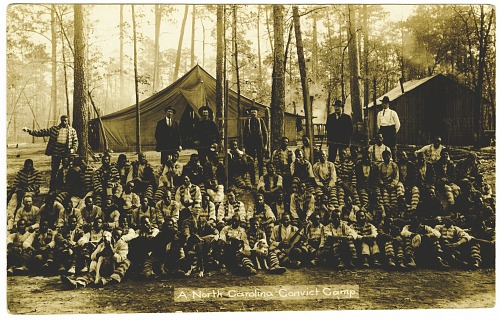

Laurinburg, N.C., ca. 1910. Courtesy, National Museum of African American History and Culture

Convict labor played an especially important role in giving North Carolina its reputation as the “Good Roads State.” In 1900 a Report from the Industrial Commission on Prison Labor marveled that the state built roads for as little as $800 a mile and was able “to guard, shelter, clothe, and feed convicts for 21 cents a day.”

As Seth Kotch at UNC-Chapel Hill notes in his splendid work of scholarship, Lethal State: A History of the Death Penalty in North Carolina, only 75 out of 2,800 inmates in the state’s prison system in 1911 and 1912 did not work on county roads, railroads or farms.

Those work camps and prison farms were marked, Kotch writes, “by horrific cruelty and neglect.” They seemed right out of slavery: the white men with guns, the violence, the chains, the bloodhounds, the relentless toil and the never-ending demand for submission.

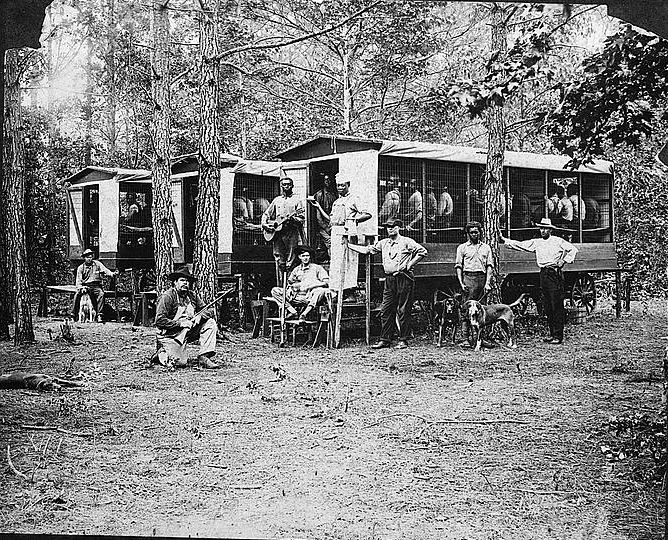

For years at a time, many of the state’s convict laborers lived in trailers with iron bar walls. Early on, horses towed those trailers from work site to work site. Appropriately called “convict cages,” they were typically very small and often housed more than 20 men.

Road building crew and “convict cage,” Pitt County, N.C, 1909. Courtesy, Library of Congress

In 1915 a state official estimated that a third of the state’s budget for road building crews went to such chain gangs. By that time, many convict laborers also worked on state farms. The first and largest state-owned prison farm, Caledonia, ranged over thousands of acres in Halifax County. More than 250 plantation slaves had toiled there before the Civil War. When I was young, I sometimes met former inmates who still referred to Caledonia as “the plantation.”

* * *

Many years have passed since I looked for Central Prison’s history in the State Archives. Many years have passed since the hunger strike, too. Those men on J-Block led me to do the historical research that I shared with you today, and I do wish we had more time to talk about them. I still think about them often, and in some ways I think I appreciate what they taught me more now than I did then.

They may have been, to borrow a phrase from Milton’s Paradise Lost for other fallen souls, “the spirits damn’d,” but they understood in a deep and insightful way that their protest was an act of claiming their humanity in a world over which slavery’s shadow still fell.

They told me this again and again: the hunger strike was about being human in a system that denied their humanity. And to my surprise, they believed that their lives had taught them something that those of us on the outside often do not see, namely that that is our struggle, too.

-End-

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE HUNGER STRIKE

I didn’t write this for the conference, but I thought some of the participants might be interested in this excerpt from a longer story that I’m writing about the hunger strike at the old Central Prison in 1982.

“The premise of I and J blocks is inherently cruel,” Denny Ray, an attorney who was head of North Carolina’s prisoner legal-aid society, told me when I visited him in the winter of 1982. J-Block was one of the Central Prison’s solitary confinement units; I-Block was the other. “It robs them of their spirit and it dehumanizes them,” Ray said.

The isolation of course took its toll. “Being locked in a 6 x 8 ft. cell can hurt a person very much,” a very understated J-Block inmate named George Ball* once wrote me.

Tensions on J-Block had begun to rise earlier that fall. According to the hunger strikers, guards had beaten one of the inmates badly. Guard brutality in general increased on the block, they told me, and the warden postponed several upgrade hearings that might have gotten some of them out of solitary confinement early.

As tensions heightened, a J-Block inmate hung himself. He was rescued before he died, but he returned from the prison’s hospital wing with bruises and a neck brace.

The sight of the neck brace grated on the other prisoners’ nerves. The air on the block crackled with tension. Every encounter between a guard and an inmate bordered on the edge of violence.

The escalating tension on J-Block reminded an inmate named James Smith* of his hometown, which was Wilmington, N.C., not far from where I grew up. Smith told me that J-Block reminded him of Wilmington just before the city exploded in race riots in 1971.

Thirty-one years old and an auto mechanic in his old life, Smith was incarcerated for second-degree murder. “Things in here could easily erupt in a riot or something one day,” he warned me.

Another J-Block inmate watched all this unfold. His name was Thomas Cranford*, and he was a legendary “jailhouse lawyer.” Almost wholly self-educated and a ward of the state since he was 12 or 13 years old, he had a brilliant, if unbridled, intellect. He once wrote to me in Latin in order to frustrate the prison officials that usually read his mail.

Cranford told me that he remembered when a group of his fellow inmates protested living conditions in the prison by slitting their wrists. One inmate or another cut himself every few minutes until the warden consented to hear their grievances.

When I got access to the hunger strikers’ prison records, I saw that five of them had a history of “self-mutilation.” One had cut himself 13 different times.

The inmates told me that wrist cutting in the prison tended to happen in clusters. One man’s anger or despair infected another man, then another and another. The hunger strike’s leaders had been determined not to allow the tensions on J-Block lead to that sort of protest again.

“They treat us like animals, so we act like animals,” Cranford once wrote me. “They treat us violently in here, then they are surprised when we don’t get rehabilitated but remain violent.”

The J-Block inmates decided that a nonviolent protest, a hunger strike, was the only way to rise above that cycle of violence. They told me that they wanted to prove, as another told me, that even the men on J-Block “deserve to be treated like human beings.” On the morning of November 8, 1982, they stuffed rags into the slots where they usually received their breakfast trays.

* At least for now I am using pseudonyms for all of the prisoners that I named above, except for Larry Darnell Williams who died some years ago, though not in the electric chair.

This is what makes Proud Boys proud?

LikeLike

Chilling account and explanation…Thanks for your work! I remember riding by those walls many times in my youth as they were on a major thoroughfare through town. No wonder shivers ran down my spine

LikeLiked by 3 people