The other night I was a guest on a digital talk radio show based in New Orleans. The show was an Afro-centric broadcast called New Orleans, Wake Up!!!!! The host, Warren Jones (a. k. a. Brother Warren), covers topics related to black survival in New Orleans and around the world.

We had only been on the air a few minutes when we got to talking about the historic ties between the African American communities on the North Carolina coast and those in Louisiana.

That wasn’t just because he was in New Orleans and I write about the history of the North Carolina coast: Brother Warren, it turned out, has deep roots on the North Carolina coast. Long before the Civil War, some of his ancestors had been slaves in Bertie County, N.C., a rural county on the west side of the Albemarle Sound that has been majority black for more than two centuries.

According to Brother Warren’s research, some of his ancestors first came to Louisiana when a Bertie County, N.C., planter immigrated there and brought his enslaved laborers with him. That was in the early 1800s and one of them was his great-great-great grandmother.

The planter’s name was Augustin Pugh (1783-1853). He was from the southwest part of Bertie County, in a swampy, low-lying section known as Indian Woods. Since the late 1710s, it had been the site of a Tuscarora Indian reservation.

Augustin Pugh, his brother Dr. Whitmell Hill Pugh and their half-brother Thomas Pugh all left Bertie County and moved to Louisiana in 1818-19.

In a family history, one of Dr. Pugh’s sons later wrote: “The brothers were the owners of many slaves and large tracts of land that had once been fertile but owing to the common custom of that day, of taking all from the field and returning nothing, they had ceased to be productive.”

After first renting a plantation at Bayou Teche, west of New Orleans, they settled on Bayou Lafourche, south of New Orleans and north of the Gulf of Mexico, in a region that people think of today as part of “Cajun Country.”

Speaking of his father, another of Dr. Pugh’s sons wrote, “Although he had many Negroes, he found great difficulty in supplying them with the necessities of life whilst the heavy growth of timber occupying the land was being destroyed and the land placed in cultivation.”

By “necessities of life,” he meant of course food, clothing and shelter.

On the labor of more than a thousand slaves, the Pughs eventually became some of the wealthiest and most influential sugar cane planters in Louisiana. By the eve of the Civil War, they owned 13 different plantations (and had part ownership in five others) in Lafourche and Assumption Parish and held more than 1,500 men, women and children in bondage.

Some of those enslaved laborers were Brother Warren’s ancestors, and some of them had been born back here in North Carolina.

The Brig Calypso

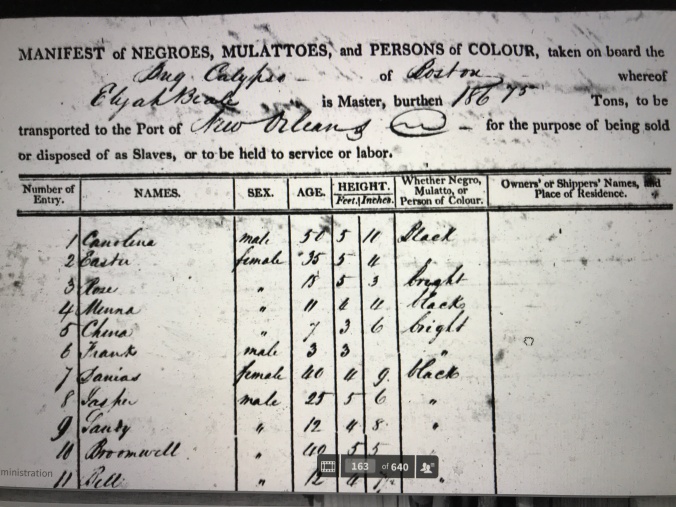

After we talked on his radio show, Brother Warren sent me a copy of a slave manifest that chronicles how some of Augustin Pugh’s slaves made the journey from Bertie County, N.C., to Louisiana.

In the early 1800s, federal law required masters of sailing vessels to submit a list, or manifest, of the African Americans that they carried in and out of U.S. seaports and their legal status. One purpose of those manifests was to monitor compliance with the Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807. That law forbade the shipment of slaves into the U.S. from other nations, but allowed the slave trade to continue between seaports in U.S. states and territories.

Detail from slave manifest of the brig Calypso, April 3, 1819. National Archives, Slave Manifests of Coastwise Vessels Filed at New Orleans, Louisiana, 1807-1860; Microfilm Serial: M1895; Microfilm Roll: 1. Accessed on Ancestry.com.

Such manifests can be very informative if you’re trying to track down African American ancestors because they include the names and ages of the enslaved people who were transported between U.S. ports.

The document that Brother Warren sent me was one of those manifests.

Now preserved at the National Archives, that slave manifest indicates that 66 of Augustin Pugh’s slaves from Bertie County sailed on the brig Calypso out of Norfolk, Va., on April 3, 1819. The ship manifest lists their names: Essex, Harriet, Hannah, Sam and 62 others, including at least a few, such as Mustapha (a variant of a name for Muhammed) that are Arabic in origin.

Looking at the manifest, I was struck that 35 of Augustin Pugh’s slaves on the Calypso– more than half the total number– were ten years old or younger. The youngest, a little girl named Maloma, was only a month old.

I have tried to imagine those children aboard the Calypso, but I don’t think I can: all those young children taken from the only home they had ever known, bound for a strange new land.

Brother Warren told me that he cannot be sure that those children or the Calypso’s other slave passengers included any of his ancestors. They might have been, but he also knows that Augustin Pugh and his brothers transported many of their enslaved laborers to Louisiana by an overland route that combined a long trek west and an even longer passage down a succession of rivers.

His ancestors might have been on the Calypso or they may have been forced to take that western route. He might also have had ancestors both on the Calypso and on the journey to the west.

“Their Suffering was Great….”

According to accounts written by two of Dr. Whitmel Hill’s sons at the end of the 19th century and published in The Life and Letters of Charles Francis Degahl (another of his descendants) in 1949, the Pugh brothers drove a large coffle of their enslaved laborers west to Nashville, Tennessee, in 1818.

Once they reached Nashville, the brothers purchased a keelboat and carried those enslaved laborers down the Cumberland River. They followed the Cumberland to the Ohio River, which flows into the Mississippi. They then passed down the Mississippi until they reached Bayou Plaquemine in Louisiana.

At that point, they passed through the Atchafalaya to Bayou Teche, where they rented a plantation for a year before moving to the more remote reaches of Bayou Lafourche.

That journey was long, arduous and dangerous, but the voyage of the Calypso may have been even worse. According to the Pugh family accounts, the children and other slaves on the Calypso suffered enormously. One of Dr. Hill’s sons, William Whitmel Hill Pugh, later wrote:

“A portion of the slaves were shipped from Norfolk to New Orleans, which point they reached after a long and tedious trip. Their suffering was great from their long confinement on board the vessel and great mortality followed their arrival on the Teche.”

Augustin Pugh’s slaves were not the only enslaved laborers on the Calypso. They were part of a cargo that was a total of 148 African American men, women and children. In addition to the 66 slaves from Bertie County, another 82 came from two plantations in Halifax, N.C., in a section of eastern North Carolina farther up the Roanoke River.

Those two plantations were owned by two other large slaveholders, Samuel T. Barnes and Benjamin Ballard, who were also relocating to Louisiana.

That’s part of what makes the Calypso’s voyage so interesting: it gives us a window into a much bigger chapter in American history.

In the early 1800s, large numbers of planters from eastern North Carolina and other parts of the Upper South began to invest in lands in Louisiana.

That land was open to those planters because the U.S. Government had purchased it from France as part of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and because of the government’s forced removal of the native peoples from their homelands, culminating in the Choctaw Trail of Tears in 1831-33.

So the slaves on the Calypso were hardly the only African Americans bound for Louisiana and other parts of the Deep South in that era. By some estimates as many as a million black people were forced to make the journey from the Upper South to the Deep South between 1790 and 1860. Planters transported some of them on rivers and by sea, but most were taken south by land.

Historians often refer to that forced migration as the “Second Middle Passage.” The first “Middle Passage,” of course, consisted of the forced transport of Africans from the continent of Africa to the Americas on slave ships.

Brother Warren told me that he is often surprised how many of his Louisiana listeners tell him that they have roots in North Carolina. Over the years, he told me, he has been especially surprised how often he hears from listeners who have roots like him in Bertie County.

From Bertie County to Louisiana

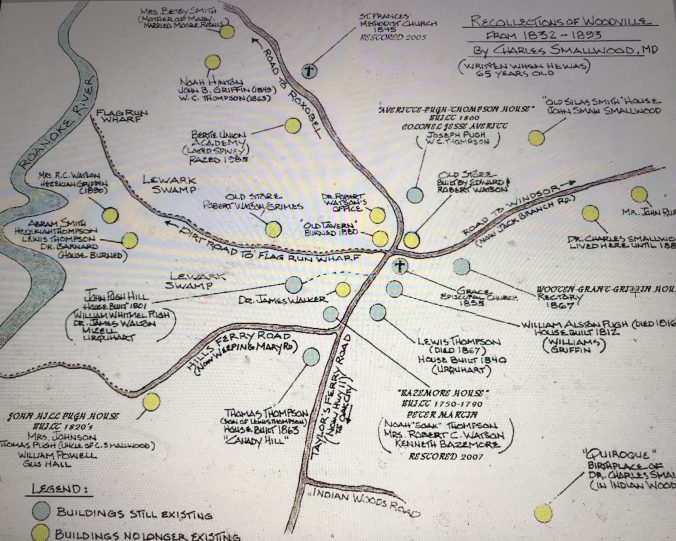

Even if we take just a tiny corner of Bertie County, say the village of Woodville, 10 miles from Indian Woods, we can get a feeling for this mass deportation of enslaved African Americans.

Augustin Pugh’s brother, Dr. Whitmel Hill Pugh, resided in Woodville, so large numbers of his enslaved laborers ended up in Bayou Lafourche when he and his brothers relocated there. In addition, around the same time, another Woodville planter, Lewis Thompson, established a plantation at Bayou Boeuf in Rapides Parrish, Louisiana. He would eventually hold nearly a thousand African Americans in bondage, many of them from Bertie County.

Modern map drawn of Woodville (Bertie County, N.C.) based on Dr. Charles Smallwood’s “Recollections of Woodville Past, 1832-1895,” probably as part of the documentation for the Woodville Rural Historic District, author unknown. Source: Historic Woodville

Yet another local planter, Peter B. Martin, also went to Bayou Lafourche. Still another Woodville resident, Col. Jesse Averitt, moved to new plantation lands in the Florida Panhandle. Another, Noah B. Hinton, picked up and moved to Madison County, Mississippi. Another Woodville planter family, the Smiths, also vacated their homeplace and re-settled in Mississippi.

An earlier guest on Brother Warren’s radio show, the Mississippi writer Freddi Evans, is a descendant of two of Noah B. Hinton’s slaves from Bertie County. Their names were Habeas and Mary, and they were her great-great maternal grandparents. Ms. Evans discussed her Bertie County roots on another BlogTalkRadio show, Bernice Bennett’s “Research at the National Archive & Beyond.” You can find that conversation between Ms. Evans and Ms. Bennett here.

Woodville was just a tiny little village– hardly that even. It was also off the beaten path. In 1820 the nearest city with more than 2,000 residents, Norfolk, Va., was 80 miles away. Yet even in that remote corner of eastern North Carolina, Woodville’s ties to Louisiana and other parts of the Deep South were strong. They drew planters south, and those planters transported an extraordinary number of African American people with them.

Between 1790 and 1830, Bertie County’s population declined by 26 percent. Of course not all those who left Bertie County went to the Deep South, but many of them did.

In the Antebellum Era, you could see the influence of this great migration up and down the banks of Bayou Lafourche: enslaved African Americans and slaveholders from Bertie County seemed to be everywhere. One of the plantations was called “Albemarle,” and one whole neighborhood on the bayou, near Napoleonville, was called “Bertie.”

In the Sugar Cane Fields

The majority of the slaves that planters brought south, as well as those that slave traders moved south, ended up on cotton plantations that stretched from the Florida Panhandle to East Texas. However, the story of the Pugh brothers and the voyage of the Calypso remind us that many thousands also ended up in the sugar cane fields of Louisiana.

For the Pughs and others who had the slaves and capital necessary to establish sugar cane plantations in Louisiana, the riches were often mind boggling.

Antebellum Louisiana produced roughly 95 percent of the cane sugar grown in the U.S. By the mid-1800s, Louisiana’s fields and industrial sugar mills were producing a quarter of the world’s supply. According to historian Richard Follett’s book The Sugar Masters, they played a major role in making Louisiana the second richest state in the U.S. in per capita wealth and the state with the third highest amount of banking capital in 1840.

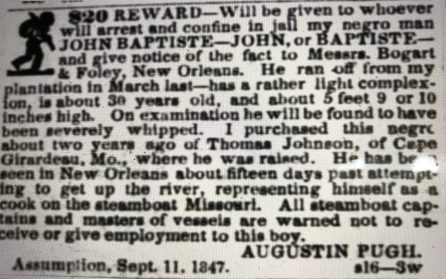

From The Times-Picayune (New Orleans, La.), Oct. 3, 1847. Accessed at Newpapers.com.

Those profits came at a dear cost to the enslaved men, women and children that worked in those fields and mills, however. The industry relied completely on slave labor and was notorious for its hardships and violence. Citing mortality statistics, some historians believe that sugar cane plantations were the single-most brutal kind of slavery in the United States.

Kahlil Gibran Muhammad, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School, was blunt when he surveyed the history of America’s sugar industry for the New York Times’ 1619 Project. He wrote, “Louisiana led the nation in destroying the lives of black people in the name of economic efficiency.”

Even after the end of slavery, the violence in Louisiana’s sugar cane fields remained legendary. The Thibodaux Massacre of 1887 is only the best known instance of violence against African American sugar cane workers.

Homecoming

Ever since we talked, I have been thinking about what Brother Warren told me about his family and about his listeners who have roots in Bertie County and in other parts of eastern North Carolina. I’ve also thought a great deal about the voyage of the Calypso.

Of course I can’t help thinking about all those little children that were shipped to New Orleans on the Calypso. This past week I found myself wondering constantly what happened to them: who did they leave behind? Did they at least have their mothers or fathers with them? Where did they end up? How did they find a way to survive?

I would like to know their stories. I would like to know what stories their descendants tell about them.

At the end of our conversation the other night, Brother Warren told me that there have recently been discussions about holding a homecoming for the descendants of all those enslaved African Americans who were taken from Bertie County in the early 1800s.

I have never heard of anything like that before. If it happens, I hope very much that I can be there. I would look forward to meeting Brother Warren, and I know it would be an extraordinary day.

Speaking of amazing acts of cultural and historical reclamation, Beyonce used Madewood, a plantation that the Pugh family’s slaves built on Bayou Lafourche in 1846, as the location for several scenes in her 2016 video album “Lemonade.” For her song “All Night” (viewed more than 100 million times on YouTube), she wrote: “Grandmother, the alchemist, you spun gold out of this hard life, conjured beauty from the things left behind. Found healing where it did not live. Discovered the antidote in your own kitchen. Broke the curse with your own two hands. You passed these instructions down to your daughter who then passed it down to her daughter.” Photo courtesy, HBO

-End-

Thank you David. Important and absolutely fascinating. I had never heard of these documents before. Once again you show your genius for using a document or a conversation to open up a much bigger story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting. Thank you for posting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

David, since you adroitly mentioned the Louisiana “purchase” and The Choctaw Trail of Tears I thought you would appreciate this link to a Heritage breed of hog intertwined with the Choctaw people. Note the livestock preservation organization is The Livestock Conservancy in Pittsboro, NC. A fascinating intersection of people, animals, history and survival.

Again a fascinating watch. With respect, Linwood

LikeLiked by 1 person

Awesome! Thanks, Linwood!

LikeLike

Thank you for this fantastic article! I am a descendant of Whitmel Hill Pugh and have done a good deal of research on this same history. In a family history book, we have an account of the move from Bertie County to Louisiana happening on river boats. It makes sense that wagons were involved as well. I’m also in contact with a descendant of folks my ancestors enslaved and were part of this forced migration, and have been comparing notes. I’d be very interested in sharing any information that might be helpful in your own research.

LikeLike

Mr. Russell, so good to hear from you. Thank you for your note. Yes, I think you’re right, it does make sense your ancestors made the journey south part by wagon but then took a riverboat as soon as they reached the Mississippi’s river shed. I would indeed love to know more about that journey, and about anything else you’ve learned about your family and the enslaved laborers who came from Bertie– as you can tell, I’m especially interested in the connections between NC and LA…. Thank you again for getting in touch. All my bests, David

LikeLike

As a Bertie county born descendant of Pughs and Thompsons, and longtime student of their history, I am thrilled to read – and pass on to many – your impressive and well presented research here. I thank you so much.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent article, I happened to find it by google. I’m a descendant of a slave brought from Maryland to Plaquemines Parish by boat in 1831. I had no idea this second migration occured, and thought all my family was brought directly to Louisiana from West & Central Africa.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - news1110.com

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist – news EvA

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - book galaxy

Pingback: Searching for America’s First Black Woman Novelist - RecentTv.com

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - BEpressNewS

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist | Old School News

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Girl Novelist - eJivi

Pingback: Escribiendo la biografía de la primera novelista negra de Estados Unidos - Notiulti

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - USA NEWS

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - The Marketing Plus

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - Harika Portal

Pingback: Searching for America’s First Black Woman Novelist – Eng.psartworks

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist – The Wall Street Post

Pingback: Searching for America’s First Black Woman Novelist

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - NewsFronTV

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - SiDETH

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - NewsAffairs

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist | The Sun Bulletin

Pingback: Searching for America’s First Black Woman Novelist - Glazzbox

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - The Daily Briefings

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - TECH AYE FOO

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist - newsplace24

Pingback: Searching for America’s First Black Woman Novelist | Hood Over Hollywood: Mature

Pingback: Writing the Biography of America’s First Black Woman Novelist – Ebonicles