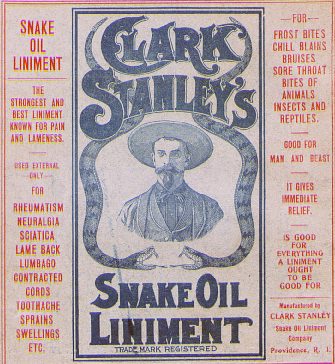

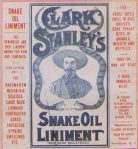

A typical ad for tonic sold at medicine shows. From True Life in the Far West (Worcester, Mass., ca. 1905). Courtesy, NIH U.S. National Library of Medicine

My neighbor Betty Motes is 93 years old now and there are not many people besides her that remember the old days in our little corner of the North Carolina coast the way she does.

Just the other day, for instance, we were talking about how she met her husband Bill back in the early 1950s. I had heard most of the story before, but this time she happened to mention that Bill took her to the Jack Roach Indian Medicine Show on their first date.

That caught my attention. I had never heard of the Jack Roach Indian Medicine Show. I didn’t even know that medicine shows used to visit Harlowe, which is the rural community where Betty was born and raised and which is also the place where my mother grew up.

But Betty told me that Jack Roach and his family brought their medicine show to Harlowe every year. Her story enthralled me, as her stories so often do, and after I talked with her I decided to do a little research and see if I could learn more about the medicine show and its history.

Today I’d liked to share what I learned about the Jack Roach Indian Medicine Show with you.

I’d also like to share what I learned about a whole forgotten world of medicine shows, little family circuses, tent theaters and other traveling shows that once wandered the backroads and little hamlets of the North Carolina coast.

I am not sure, but this unidentified photo may be Walter “Kid” Smith, a popular musician and recording artist in North Carolina and Virginia. Along with his family, he was a regular on the medicine show circuit in the 1930s and ’40s.

A Magic and Punch Man

When I talked with Betty, she recalled that the Jack Roach Indian Medicine Show always seemed to arrive in Harlowe in the springtime.

Harlowe is located on the central part of the NC coast, partly in Craven County (shown here) and partly in Carteret County, just to the south and east. Courtesy, Wikipedia

When she and my mother were little girls, the Roaches arrived in a horse-drawn wagon that made its way down the old dirt road that later became State Highway 101. As the years went by, they showed up in a Model-T Ford, and Betty thinks that they had a truck for a time, too.

They set up camp near the turn to Adams Creek, just up from the old dance hall and a stone’s throw from Lionel Connor’s general store. They’d stay a few days and do a show every night, then they’d move on to their next stop.

When I did some library research on the medicine show, I discovered that Jack Roach and his wife, the former Anna Aydt, both came out of vaudeville in New York City.

Their daughter Mae, who also became a medicine show performer (but is best remembered for running a gorilla wrestling park in Florida), always joked that she was the child of a roach and an ant.

Jack, it turned out, grew up in Durham, N.C., but he and Anna got their starts in vaudeville in or about 1911.

According to records at the Circus Historical Society, Jack began his career as what they used to call a “magic and punch man.”

As a magic and punch man, he entertained vaudeville audiences with magic tricks and puppet shows in the zany, slapstick and extremely un-PC style of Punch and Judy, which was a kind of puppet theater that had been very popular in Europe in the 1700s and 1800s.

(Scholars say that, if you go way back, Punch and Judy shows actually originated in a 16th-century Italian form of popular theater known as commedia dell’arte.)

By the time Jack and Anna Roach got into vaudeville, the height of its popularity had already passed though, at least in New York City. To a large degree, that was because of the rising popularity of movies.

Some of the vaudeville performers of that era, and even later ones, successfully made the transition from the stage to film and radio. Some became stars that are still remembered today—Abbot and Costello, Bob Hope, Sammy Davis, Jr., Judy Garland and The Three Stooges, among others.

Moe Howard, Curly Howard and Larry Fine–The Three Stooges– got their start in vaudeville in the 1920s and were still one of the country’s most popular comedy acts in the 1960s.

But the Roaches and many other vaudeville performers gave up trying to make a living in New York City and hit the road.

According to old issues of Billboard magazine (which used to cover the medicine show circuit almost as assiduously as it did Hollywood), Jack and Anna Roach did a little bit of everything in the traveling show business in the 1910s and ‘20s. They performed in circuses, took traveling museums on the road and acted in what people used to call tab and repertory shows.

Museums, in that sense, were traveling collections of oddities and wonders. They were sort of like mobile curiosity cabinets. The whole “museum” usually occupied a single wagon or truck or was set up under a tent, and of course the proprietor charged admission.

The “Crime Museum,” a traveling museum set up at a migrant construction workers camp near Fort Bragg, N.C., ca. 1939. The museum highlighted famous criminals but also included George Washington and the boxer Joe Louis. The museum’s proprietor said that he wanted to show visitors the good things that could happen to them “if they went straight.” Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Tab shows featured short, lively “tabloid” versions of musical theater, and they were often performed under tents, too. Many were very low-budget adaptations of Broadway shows.

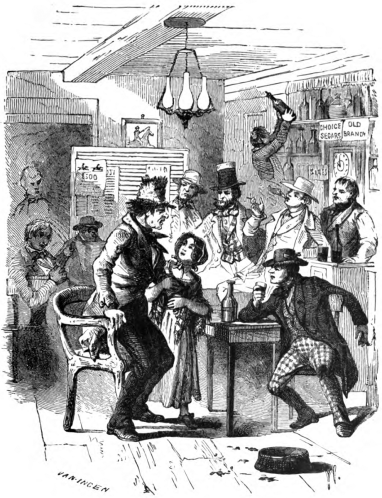

Itinerant theater companies also put on repertory, or “rep,” shows that traveled around the country, often performing the same plays year in and year out. Some classic tent rep shows included Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Ten Nights in a Bar Room and Bertha the Sewing Machine Girl.

“Oh father won’t you come home?,” a scene from the 1882 Porter and Coates edition of Timothy Shay Arthur’s 1854 temperance novel, Ten Nights in a Bar Room. It was the 2nd most popular novel in Victorian America, after Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Plays based on the novel were extremely popular on the vaudeville and medicine show circuits (though often in parodied versions).

Most were threadbare outfits. The lead actor might also do makeup, take tickets before the show and play in the orchestra at intermission. But their shows were often wildly entertaining and a load of fun—and they drew crowds all over small-town America.

Apache Jack Tonics and Tooth Powders

In an interview with the Tampa Bay Times (17 Jan. 1973), Jack and Anna’s daughter, Mae Roach Noell, remembered that people called her father “Doc Roach” when the family first set out on the medicine show circuit in 1928. He was, she said, a man of many talents.

He often started the shows by doing a ventriloquist act. His dummy—which he had carved himself— told stories and made jokes, usually at his expense, while he played the straight man.

At their shows, her dad also did what people in the trade called the “lectures”— in between acts, he pitched tonics, salves, liniments, “pep pills” and tooth powders that he assured his audience would lead to good health and long lives. They carried the “Apache Jack” label and came out of Cincinnati.

Mae once compared their medicine show to broadcast TV: you did not have to buy a ticket to the show, but her family hoped that the entertainment would put you in the mood to buy something.

In between Jack Roach’s lectures, the rest of his band of troubadours beguiled audiences with what amounted to a variety show. They put on skits, did comedy duos, performed magic acts and and played games of chance.

They might also have done a little mind reading, which was very popular on the medicine show circuit at that time.

Sometime after 1939, the Roaches also began traveling with a small menagerie. They often had chimpanzees, or sometimes a baboon, and onlookers had the opportunity to box or wrestle them, no charge. (More on that later.)

A hand-cranked Victrola often provided the music, though Mae Roach also played the ukulele. Many medicine shows featured a banjo or fiddle player.

Even as a small girl, Mae danced in the show, played parts in comedy skits and pitched the family’s line of Apache Jack tonics and salves.

Mae Roach Noell (left) had a long career in traveling shows. Even after she and her husband Bob Noell (on right) retired from show business in 1971, they occasionally performed medicine show and vaudeville-style skits at fundraisers and other special occasions. This photo was taken at the Florida Folk Festival in 1983. Courtesy, State Library and Archives of Florida

Blackface and Minstrel Acts

Most of the show’s skits and comedy routines came straight out of vaudeville. Over the generations, some of them grew so familiar that even little boys and girls in places like Harlowe knew them by heart.

“Those skits were sort of folk art handed down with variations,” Mae told the Tampa Bay Times back in 1973.

Unfortunately, many were racist in a way that makes us cringe today. That was especially true when Mae was traveling with the family’s medicine show in the 1920s and ’30s.

The whole premise of the medicine show– the Jack Roach Indian Medicine Show– was of course rather strange itself, though hardly unusual: the commercial use of Native American images in advertising, merchandising and trademarks was widespread at that time.

From Madison Avenue to, well, Harlowe, businessmen used romanticized images of the country’s indigenous peoples to extoll the supposedly healthful benefits of products ranging from snake oil to smoking tobacco.

Kickapoo Indian Medicine Co. label (Boston, ca. 1910). Courtesy, National Institutes of Health Library

Of course, none of that advertising and marketing acknowledged the toll that dispossession, genocide and oppression had taken on the health and well-being of the country’s indigenous people.

American Indian performers sometimes headed up medicine shows. One example is Leo Kahdot, a.k.a., Chief Thundercloud, who often performed in North Carolina. A Potawatomi Indian from Oklahoma, he began his career as a vaudeville piano and trumpet player. As late as 1972, he and Peg Leg Sam, an African American performer, put out an album of their songs and stories, based on recordings made in Pittsboro, N.C.

In a similar vein, at least in the 1920s and ’30s, the Roach family’s show featured vaudeville acts that came out of the minstrel tradition. The little band’s members performed those acts in blackface and, as in all minstrel acts, lampooned African Americans as dim-witted, lazy and buffoonish.

I doubt the performers thought about it much, minstrelsy and blackface were so common in the United States at that time. But without a doubt, minstrelsy both reflected and reinforced the white supremacy of the age.

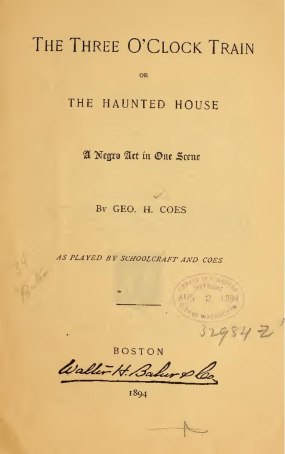

In her interview with the Tampa Bay Times, Mae mentioned at least two of the family’s skits that, while vaudeville standards, had their roots in minstrelsy and were always performed in blackface. The two that she mentioned were “Pete in the Well” and “The Three O’Clock Train.”

Published in Boston in 1894, this version of “The Three O’Clock Train” was one of a large compendium of what the publisher called “Darkey Plays” geared to minstrel and vaudeville acts, as well as to medicine shows. Courtesy, Library of Congress

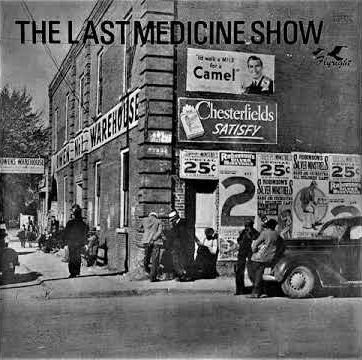

Minstrelsy was the most common form of popular entertainment in America in the 19th century. Medicine shows, I learned, unfortunately, were one of the ways that that tradition of minstrelsy was kept alive deep into the 20th century.

Hollywood, though, was not much better. In the 1920s and ’30s, even Hollywood stars as mainstream as Bing Crosby, Judy Garland, Fred Astaire and Shirley Temple performed in blackface in Hollywood films.

A typical medicine show, including an African American performer in blackface and a man in an Indian headdress, Huntington, Tennessee, 1935. Photo by Ben Shahn. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Even after the Second World War though, many medicine shows continued to feature a blackface comedian, usually called “Jake” or “Sambo,” as master of ceremonies.

As I learned more about the history of medicine shows, I came to understand that, like so many things in life, they were many things at once. Without a doubt though, they were a complicated mishmash of show business’s best and worst, and a reflection of both the lightness and darkness within performers and audiences alike.

Medicine show performer in blackface and an African American puppet, Huntington, Tennessee, 1935. Photo by Ben Shahn. Courtesy, Library of Congress

A Traveling Menagerie

Another aspect of the Jack Roach Indian Medicine Show was a small traveling menagerie, a collection of just a few wild and often exotic animals that was meant to entertain the show’s small town and country crowds in much same the way as a city zoo might in Philadelphia or Boston.

Such menageries had been around since antiquity, but traveling shows of that kind had grown especially popular in Europe and America in the 1700s and 1800s.

I do not know exactly when Jack and Anna Roach first traveled with a menagerie, but it was apparently sometime in the 1940s.

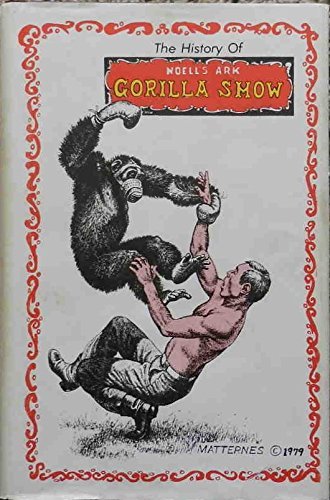

In The History of Noell’s Ark Gorilla Show, Mae (Roach) Noell described her and her family’s gorilla show that was open from the 1940s to 1971.

In Billboard magazines dating from 1949 to 1953, I found references to the Roaches carrying a kangaroo, a black bear, a Scottish ram, three chimpanzees and a baboon (though not all at the same time).

The baboon, who was named Jo Jo, was apparently a handful.

In a letter that was published in Billboard on March 15, 1952, Jack Roach reported, “My baboon, Jo Jo, made a getaway last week and sent a dog off on high; gave two cats running fits; threw a woman into hysteria; caused a cow to jump a 42-inch fence; and then went on a sit-down strike on top of a telephone pole.”

The medicine show’s troupe did not only display the animals, though. By the early 1950s, monkey wrestling—human versus chimpanzee, gorilla or baboon— was one of the show’s regular attractions.

Any volunteer in the audience was welcome to take a turn in the “monkey cage.”

Several years ago, one of my Down East friends, the extraordinary cultural anthropologist and fishery activist Barbara Garrity-Blake, actually interviewed someone that remembered when the Jack Roach Indian Medicine Show brought its monkeys to his home on Cedar Island, N.C.

The man’ name was Gary Day. Along with his nephew John, Barbara asked Mr. Day about his memories of the show in the 1940s.

Mr. Day recalled that the show had three chimpanzees at the time.

“You could get in the cage and box that male chimpanzee. They put a muzzle on him so he couldn’t bite you. Had gloves on his paws,” he said. (Both boxing and wrestling were apparently options.)

One of my cousins in Harlowe also remembers the monkey wrestling, though none too fondly. He was a small child in the late 1940s or early 1950s when the Jack Roach Indian Medicine Show was still coming to Harlowe.

The other day he told me that some of the grown-up men thought it might be amusing if they scooted him and a few other local boys into the medicine show’s monkey cage. The boys did not agree.

“It wasn’t monkey wrestling,” he told me, still not finding it a bit funny. “We just ran and tried to keep away from them.”

Monkey and gorilla wrestling became more than a sidelight for Mae Roach, Jack and Anna’s daughter.

Mae and Bob Noell’s “Noell’s Ark Gorilla Show” in Tarpon Springs, Florida, ca. 1950-1970. Courtesy, Aleada Siragusa

Mae met her husband, “Dakota Bob” Noell, when the Roach’s medicine show crossed paths with the San Blas Indian Remedy Show in a small town in Virginia in 1931. Noell, who was only 19 at that time, was a ventriloquist and a juggler from, of course, the Dakotas.

After they got married, Mae and Bob ran a variety of traveling shows, but eventually focused on monkey and gorilla wrestling. They called their show “Noell’s Ark.” For six months a year, they carried their apes to small towns and little country places over a broad swath of America.

At every stop, local people had the opportunity to take their chances in the monkey cage. According to Mae, the apes always won. In one interview, she recalled that, in Bladenboro, N.C., their gorilla Kongo threw a man so far that he hit Bob and knocked out two teeth.

In the wintertime, when they were not on the road, Mae and Bob ran a roadside park in Tarpon Springs, Florida, that featured gorilla wrestling. They operated “Noell’s Ark” down there every winter until 1971.

The Tent Picture Game

While Jack Roach largely stayed on the medicine show circuit, he did try other things, too.

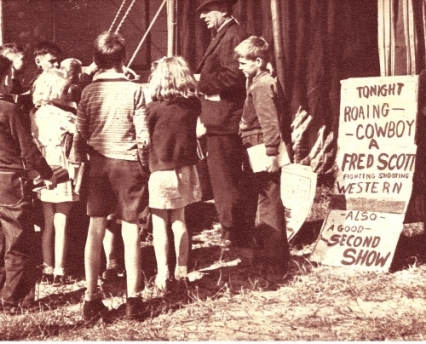

For a time, roughly between 1940 and 1942, Jack got into what Billboard called the “tent picture game,” taking movies to rural communities that didn’t have a theater and showing them under a tent.

Children at a traveling, or “nomad,” theater in Wade, N.C., in the 1940s. Millions of Americans saw movies at nomad theaters in the 1930s and ’40s. Courtesy, National Picture Monthly, March 1944

A couple years later, Jack was pitching “trick playing cards” at a department store in Chicago when the medicine show wasn’t on the road. He and his son Charles also operated a traveling photo gallery when they didn’t have other gigs.

By the early 1950s, when my friend Betty and her future husband Bill Motes attended the medicine show in Harlowe, the Roach clan was scattered across the southern states.

On May 23, 1953, for instance, Billboard reported that Jack had just “made a few spot in Alabama.” He and Anna had then gone to Georgia. At the same time, their grown son J.J. Roach and his chimp Bo Bo were on the road in Mississippi, while Mae and her husband Bob were on the road with their gorilla show.

“A Girl Show, a Monkey Show and a Snake Show”

At first I looked at the Roaches as solitary troubadours, pilgrims on the road with no place to call home. And in a way that was true. But in another way, I came to appreciate that they were also part of an extraordinary guild of itinerant circus, fair and medicine show performers that was its own kind of community.

Jack and Anna, for instance, always seemed to know where other traveling shows were and often visited them.

In Billboard’s October 27, 1947 issue, for example, I learned that Jack visited the “Mustard and Gravy and Gorilla Show” when it was in Lucama, a little tobacco farming community in Wilson County, N.C.

Evidently his son-in-law Bob Noell had brought some of his and Mae’s gorillas and teamed up with Mustard and Gravy for the tobacco market season– the tobacco markets were always a big draw for traveling shows.

Frank “Mustard” Rice (center) and Ernest “Gravy” Stokes (right) first made their name as country musicians and comedians in Wilson, N.C., but later appeared in Hollywood movies under contract to Columbia Pictures. They often appeared in deeply racist blackface acts that lampooned African Americans as indolent and buffoonish. Photo from The State magazine, Oct. 5, 1946.

The show’s headliners, Frank “Mustard” Rice and Ernest “Gravy” Stokes, were first discovered on a radio show’s talent contest in Wilson, the seat of Wilson County, in the early 1930s.

They played country music (people often called it “hillbilly music” in those days) and regrettably did a minstrel act in blackface as well.

Early in the spring, the Roaches often visited other traveling shows as their performers gathered in winter quarters and got ready to hit the road.

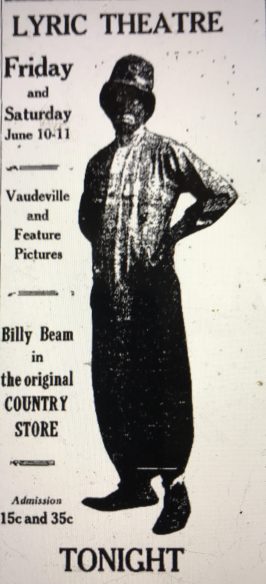

In March of 1952, Jack reported in Billboard that he had visited Billy Beam’s medicine show in Faison, in Duplin County, N.C. Beam’s show was called the “Shufflin’ Sam Minstrels” (more blackface) and was made up of African American musicians and comedians.

Originally out of Muskogee, Oklahoma, Beam had been performing in minstrel and medicine shows for more than 30 years by the time that Jack Roach visited his show in Faison, N.C., in 1953. Advertisement in the Fayetteville Daily Democrat (Fayetteville, Ark.), 10 June 1921.

Around the same time, Jack also visited an outfit called Lawrence Greater Shows at its winter quarters in Dunn, in Harnett County, N.C. It specialized in rides and sideshows and was getting ready to head out on the county fair circuit.

A Jewish Polish immigrant named Samuel Lawrence, an old vaudevillian, had started Lawrence Greater Shows in New York City in 1918.

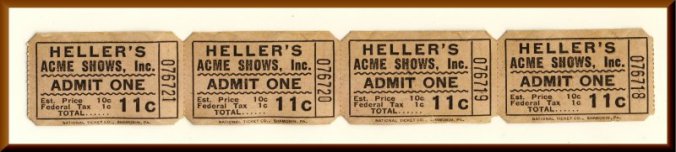

That spring Jack Roach also visited yet another traveling show that was wintering in eastern North Carolina—a carnival outfit, Harry Heller’s Acme Shows, in Wallace, in Duplin County.

Heller, an old vaudeville performer and circus clown, had run his own carnival for almost 40 years when Jack visited him in Wallace.

Two years later, in 1955, Billboard reported that, at age 72, Heller was whittling down his carnival to just rides and concessions. However, he was apparently in negotiations with another operator “to provide a Girl Show, a Monkey Show and a Snake Show” that would accompany his outfit on the road.

Wintering on Cedar Island

If there was a place where the Jack Roach Indian Medicine Show went into winter quarters regularly, I did not discover it. But in that interview I mentioned earlier, local resident Gary Day did recall that the medicine show spent the winter on Cedar Island, in Carteret County, N.C., at least a couple of times in the 1940s.

“They stayed here for two winters and a summer once,” Mr. Day recalled when his nephew and Barbara Garrity-Blake visited him on the island.

Mr. Day recollected that the Roaches lingered on the island so that their children could go to school for a time. He remembered that they were traveling in a truck by that time, burnt coke in a barrel to keep warm and did odd jobs around the island to bring in a little money until they went back on the road.

His were a child’s memories: above all, he remembered their popcorn machine and the show’s three chimpanzees.

The thought of the medicine show on Cedar Island gives us a good feeling for the kind of places where Jack and Anna Roach felt at home– and maybe the kind of place where they were most appreciated.

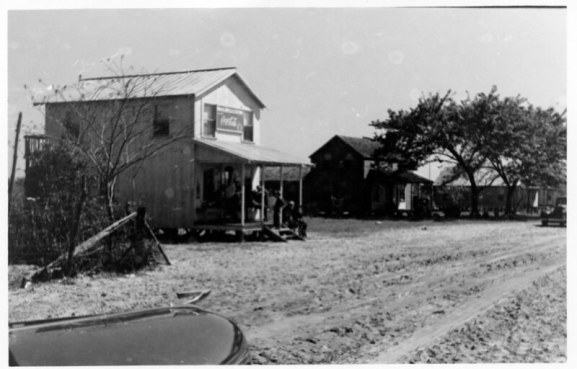

At that time, Cedar Island seemed like the end of the Earth to people that lived even in towns as close as New Bern and Greenville. The little community had a lone church, a tiny school, a store or two and a few hundred people that largely made their livings by fishing and hunting.

Country store on the main road on Cedar Island, N.C., ca. 1937-40. Photo by Charles A. Farrell. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

On Cedar Island, miles of sea and salt marsh surrounded the villagers. Before the Second World War, the nearest town was a half day’s journey away. The arrival of the medicine show must have been a thrill, just as it was for my friends and family in Harlowe.

As I learned more about these old traveling shows, I thought a lot about the Jack Roach Indian Medicine Show’s time in Harlowe and what it must have been like.

In interviews, Mae Roach Noell always said that she remembered, above all, how happy people were and how laughter and joy filled the air when she and her family were performing– so I imagine a crowd of people there in Harlowe, a bunch of them my cousins, gathering around the stage at dusk.

I see the men in their overalls and brogans, the women in their homemade dresses, if it was the ’30s, some of them straight out of the fields, the whites upfront, the blacks in the back, the way that they did things back then.

Then I imagine the night air filling with laughter and music and a band of players, a little rickety, more than a bit out of step with the modern age, conjuring a little magic out of thin air.

I grew up in the 1930’s in a small industrial town in Ohio and remember various food trucks and an occasional huckster on the street who attracted the women to see what was for sale, etc. I don’t remember medicine persons, but do remember a man with a monkey who was a general attraction. The unique summer time activity was donkey baseball teams that came to town for their games.

Bill

LikeLiked by 2 people

Lovely, as always. Reminds me of the traveling circus in the Philadelphia suburbs of the 1950’s, and the tinker on the Skyline Drive at the same time, walking beside his cart full of pots and pans, pulled and trailed by goats–if memory serves. Here’s line I especially like: “like so many things in life, they were many things at once … a complicated mishmash of show business’s best and worst, and a reflection of both the lightness and darkness within performers and audiences alike.” As usual, I also love the last paragraphs, the brogans and the magic. Thank you, also as always.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Delightful stories! I appreciated the way you shared the information about how these “black face performances” contributed to our justification of white supremacy in the past. At best, it’s a tricky topic to write about.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My mother taught at Salter Path’s one-room schoolhouse in the 30’s. She recalled a medicine show that came to the community at that time. Apparently, the show got a little out of hand when the emcee offered a diamond ring as a prize in a game of chance, and a Salter Pather, who had a little too much to drink, kept insisting that he was going to get the ring. Then when everyone started laughing at him, he threatened to go home and get his shot gun. At that point, mayhem…everyone tried to get out on the door at the same time and even the windows. My mother took my brother, who was under the age of six, and ran into the oaks up on a sand dune. Fortunately, the man was bluffing, and no one was hurt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful piece. Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The “tinker on the Skyline Drive at the same time, walking beside his cart full of pots and pans, pulled and trailed by goats” in the 1950s, referenced by Lynn Montague above, may well be the oft-seen Goat Man, observed all around the South during that era — Jim Wann recalls him well from his visits to Chattanooga. The Goat Man makes a highly-recognizeable appearance later, as himself, a minor character in Cormac McCarthy’s 1979 novel “Suttree.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

This all reminds me, very much, of Flannery O’Connor’s novel Wise Blood. Especially the gorilla. I loved both the book and the John Huston directed movie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You mention the show setting up near the dance hall in Harlow. I went to Harlow only 1 time in the 60s at night and there was a black night club with the most awesome oak trees. Is that the same place?

LikeLike

Hi Nancy, no, I don’t think so. This dance hall was located right on Hwy 101– it’s now parts of 2 homes! I think the one you remember with the big oaks was a little ways up the Adams Creek Road! Good memory!

LikeLike