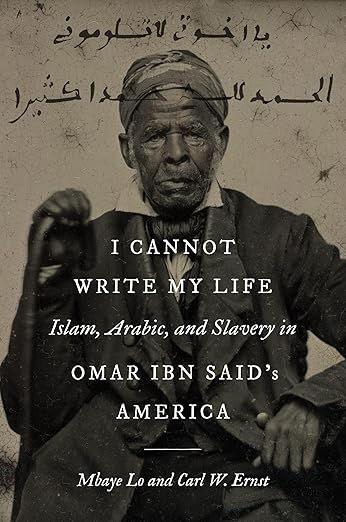

Taken from the lands along what is now the border of Senegal and Mauritania, Omar ibn Said was a Muslim scholar who was enslaved in North Carolina’s coastal region from 1807 until his death in 1863. Written in Arabic, his autobiography is the only known American slave narrative written in a language other than English. Book cover image courtesy of the University of North Carolina Press

I first read Mbaye Lo and Carl W. Ernst’s I Cannot Write My Life: Islam, Arabic, and Slavery in Omar ibn Said’s America nearly two years ago, when it was first published by the University of North Carolina Press.

The book made a deep impression on me then, and it did so again when I had occasion to re-read it recently.

Today I would like to share a little bit about why I find I Cannot Write My Life so compelling– and why it has special resonance for those of us interested in the history of the North Carolina coast.

* * *

Omar ibn Said– Omar– was born in Futa Toro, a region, he wrote, between “the two rivers” (parallel branches of the Senegal River), along what is now the border of Senegal and Mauritania.

He was born there in or about 1770. The young Omar then went on to study at Islamic centers of learning there in Futa Toro and also in Bundu, a region between the Senegal River and the Gambia River that Lo and Ernst describe as “a multicultural center of learning, a refuge for fugitive Muslims and persecuted scholars.”

For 25 years, Omar was a scholar and teacher in those Islamic schools that were a central part of Arabic intellectual life in West Africa in the late 18th century, when he was a young man.

That life ended for Omar however in 1807, when he was captured in Futa Toro, sold into slavery, and sent to America.

In his autobiography, Omar wrote:

“There came to our country a large army. It killed many people, and brought me to the big sea, and sold me into the hands of a Christian who bound me and sent me on board the big ship in the big sea. We sailed upon the big sea a month and a half, until we arrived at a place called Charleston….”

Omar spent the last half century of his life enslaved in the coastal plain of North Carolina. At times, he was held in bondage in Wilmington. At other times, on a plantation in Bladen County.

In 1831, he wrote the autobiography that has come to be known as The Life of Omar ibn Said. (Omar’s handwritten original is now in the Library of Congress.) For me it is one of the most singular literary manuscripts in the early history of the United States of America.

(How Omar came to write the Autobiography, and for what reason, and whether it was under compulsion or an act of free will, are matters discussed in I Cannot Write My Life.)

Written in Arabic (it is the only American slave narrative written in a language other than English), Omar’s autobiography has been translated into English multiple times, has been studied by many scholars, and has been written about extensively.

It has also inspired artistic works, including Rhiannon Gidden’s Pulitzer Prize-winning opera Omar.

Rhiannon Giddens’ opera Omar premiered at the Spoleto Festival USA in Charleston, S.C., on May 27, 2022. Photo courtesy, rhiannongiddens.com

Yet for all that, I found that Professors Lo and Ernst apply a special kind of scholarly expertise to Omar’s writings that has not been seen before and that profoundly changes how we understand Omar and his times.

Born and raised in Senegal, Professor Lo now teaches in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at Duke University, where one of his central research interests is the Arabic and Islamic literary traditions of West Africa.

His co-author, Carl W. Ernst, is a distinguished professor emeritus of religion at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Ernst is a specialist in Islamic studies, and his scholarship is grounded in the translation and study of Arabic, Persian, and Urdu literature.

Among his many books, he has done a literary translation of the Arabic poetry of al-Hallaj, an early Sufi who was martyred in Baghdad in the year 922.

Based on what I have seen in I Cannot Write My Life, Lo and Ernst are exceedingly analytical and cautious scholars. Their tone is measured. Their use of historical manuscripts is careful.

But there is a moment, early in the book, when it seems as if they can barely contain their outrage at what they consider Omar’s mistreatment at the hands of Western scholars.

On that point, they do not mince words.

“From the time when Omar ibn Said reached American in 1807, as an enslaved African Muslim scholar, virtually everything written about him was a lie,” they write.

The two scholars write as if they have witnessed an act of great disrespect committed against Omar and his memory.

After reading I Cannot Write My Life, I could not disagree with them. But because of Professors Lo and Ernst, we can all now gain a far deeper appreciation for Omar and for the presence of Arabic and Islamic culture in Early America.

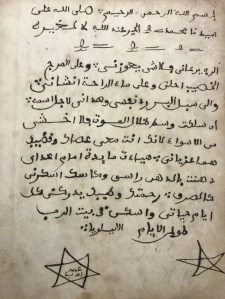

Omar ibn Said inscription, Eliza Owen journal, Owen and Barry Family Papers, New Hanover County Public Library, Wilmington, N.C.

The Misreading of Omar’s Autobiography

Professors Lo and Ernst sternly take earlier writers on Omar’s life and writing to task on two main fronts.

First, they fault them for approaching The Life of Omar ibn Said without having the necessary knowledge of Arabic and for relying on, or making, poor translations of Omar’s writings.

In the appendices to I Cannot Write My Life, Professors Lo and Ernst provide new English translations of all of Omar’s surviving writings, including his autobiography, approximately 12 letters, several inscriptions, and the margin notes that he made in an Arabic language Bible that had been given to him.

Second, the two scholars cannot hide their incredulity that earlier scholars had not done more to see Omar’s writing within the Arabic and Islamic literary traditions of West Africa in which he was educated and wrote.

Without that understanding, they argue, Omar’s written manuscripts are bound not to be understood properly and are likely to be misinterpreted.

In the final chapter of I Cannot Write My Life, Lo and Ernst also document a long history of scholars willfully misinterpreting Omar’s writings.

In persuasive fashion, they argue that many previous interpreters of Omar’s writing have purposefully contorted his words to bolster their own agendas, usually with respect to Christianity or white supremacy.

Many of those scholars and commentators have claimed that Omar turned away from Islam and converted to Christianity while he was in America. Others argued that he did not seek out or desire his freedom, and that his life story attested to the benevolence of American slavery.

All such assertions, Lo and Ernst insist, were patently false.

The Mukhtasar of Khalil

The part of I Cannot Write My Life that stirred me most deeply was Lo and Ernst’s identification and discussion of specific Arabic theological texts and poetic works that they found quoted in Omar’s writings.

These, I found, gave me insights into Omar’s Islamic schooling, his faith, and his moral outlook in ways that I could never have imagined– as well as far greater insight into what kind of man he was.

As they proceed through his writings, they point out many of Omar’s quotations from Qur’anic sura, parse their meaning, and discuss them in the Islamic theological context in which he was writing.

However, they also identify quotes and references to other Arabic literary texts in Omar’s writing.

They note, for instance, that, on more than one occasion, Omar quoted passages from a landmark manual of Maliki jurisprudence called the Summary (Mukhtasar) that was written by an Egyptian jurist named Khalil ibn Ishaq al-Jundi in the 14th century.

Usually called the “Mukhtasar of Khalil,” the manual was a standard part of the curricula at the Islamic centers of learning in which Omar studied in the late 18th century and, according to Lo and Ernst, is still considered the most authoritative legal manual by North and West African Muslims.

According to our authors, Omar quoted the Mukhtasar of Kahlil twice in his autobiography and once in the margins of his Arabic language Bible.

Lo and Ernst also observe that, in an 1853 letter, Omar quotes from a related work called The Epistle (Kitab al-risala).

The Epistle was written by Abi Zayd al-Qayrawani (922-996), a Malaki scholar who was a leading thinker in the Ash`ari school of thought, one of the three main branches of Suni Islam.

A Poem by Abu Manyan Shu’ayb

Another letter from Omar, apparently written to the man who held him in bondage and that man’s brother in 1819, was an especially rich source for seeing a variety of Omar’s intellectual influences.

Letter from Omar ibn Said to John Owen, ca. 1819. Courtesy, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

In I Cannot Write My Life, Lo and Ernst identify the l819 letter as a sermon and argument in which Omar expresses his desire for his freedom and for his return to West Africa.

They observe that Omar cites several Qur’anic sura to support his argument. But in that same letter, he also quotes from other classical Arabic works of literature and theology.

One, they inform us, was “The Pearl Necklace of the Path,” a Sufi poem by the North African scholar al-Hawdi al-Tilimsani (d. 1505).

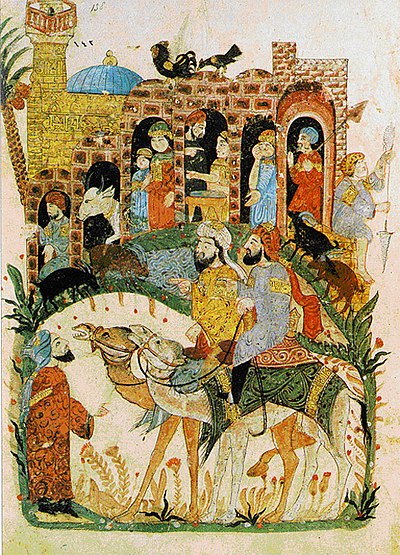

Another is a verse from a poem by Al-Hariri al-Basri (d. 1122), a famous poet from Basra, in what is now Iraq.

This is a miniature painting called “Discussion Near a Village” by aḥyā ibn Maḥmūd al-Wāsiṭī that is one of the illustrations in a 1237 edition of al-Hariri’s Maqamat al-Hariri. Painting in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

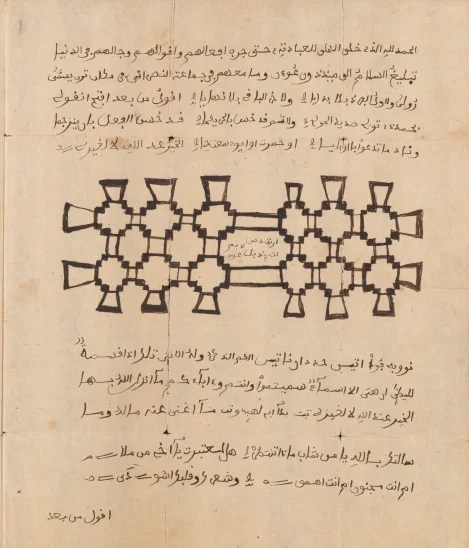

A third line of verse quoted in that letter comes from Alfiyya (Thousands), a popular versification of the rules of Arabic grammar by the Arab grammarian Ibn Malik. It, too, would have been commonly used in the kinds of Islamic centers of learning where Omar studied.

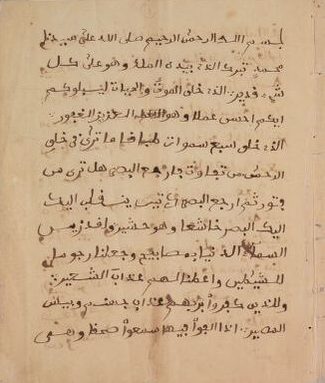

First page from a copy of the Alfiya, a rhymed book of Arabic grammar written by Ibn Malik in the 13th century. From the collection of Mullah Qasim Effendi Al-Mufti

Ibn Malik was originally from Andalusia, which at that time referred to the entirety of the Muslim-ruled part of the Iberian Peninsula, not just the southern region of Spain that is called Andalusia today. However, he lived and worked for many years in Damascus and died there in 1274.

Finally, again in that same letter seeking his liberation, Omar quotes a segment of a poem by Abu Madyan Shu’ayb, a scholar whom Lo and Ernst describe as “the most revered Sufi saint of North Africa.”

Abu Madyan, as he was commonly known, was born near Seville, again in Andalusia, in the 12th century. The poem that Omar quoted is called “The Pearl Ode in A.”

Lo and Ernst commented on the quoted passage in this way:

“The verses quoted by Omar… speak to someone growing old, warning him that the end is coming, and that he is an idiot or a fool to ignore it…, [a]… stern warning [that] is remarkable coming from someone they enslaved.”

In all, according to Lo and Ernst, Omar quotes not only the Arab grammarians, but also three Muslim theologians and two Sufi mystics, as well as the sayings of the Prophet Muhammed.

All open new windows into understanding and appreciating Omar’s surviving manuscripts in a way that has not previously been done.

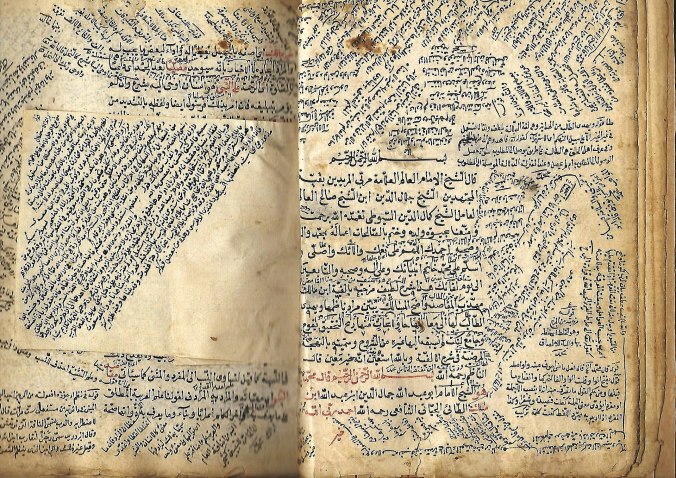

The first page of Omar ibn Said’s The Life of Omar ibn Said, 1831. From the Omar ibn Said Collection, Library of Congress, Washington, DC

“Messages in bottles, cast out to sea”

There is much else in I Cannot Write My Life worth discussing, but I hope that is enough for now to give you a sense of the kinds of things you will discover if you take the time to delve into this deeply important book.

By way of conclusion, I can do no better than quote the words with which Mbaye Lo and Carl W. Ernst end their book.

“Returning to the question of Omar’s voice, we are still faced with its paradoxical qualities. Nominally addressed to white enslavers, his documents are written with materials that could only have been read by fellow scholars trained in Islamic seminaries.

“Knowing he had no audience, he declared, `I cannot write my life.”’When commanded to do so, he . . . wrote sermons to his enslavers, filled with harsh condemnations of the arrogance of the rich and powerful.

“He dabbled in his Arabic Bible, but he did not read it closely. He evidently did not self-censor, since no one could read what he wrote.

“More than anything else, his writings resemble messages in bottles, cast out to sea in the hope of reaching unknown readers capable of reading and understanding him. His appeal to return to Africa went unheeded.

“But we can hear that appeal today, if we take Omar’s writing seriously, and stop listening to the distorted tales of enslavers and missionaries. This means adding the Arabic literature of Africa to the shelves of world literature that Goethe imagined.

“Then we might think of Omar ibn Said back in Africa, by the two rivers. Can his messages in bottles be read? Can Omar’s voice be heard? It depends on how well we can listen.”

A brief note: I am not sure it is necessary to say, but in the interest of full transparency, I want to note that Mbaye Lo and Carl Ernst asked if I would read and comment on an early draft of one chapter of I Cannot Write My Life, which I was very happy to do.

Fascinating.

LikeLike

Thank you for this reverential piece on a priceless book about a priceless man.

LikeLike

I have never heard of this scholar/ slave and thank you so very much for introducing him. It is especially timely given todays Supreme Court ruling allowing the Trump administration to send unlawful immigrants to other counties such as Sudan. We haven’t progressed much in 200 years.

LikeLike