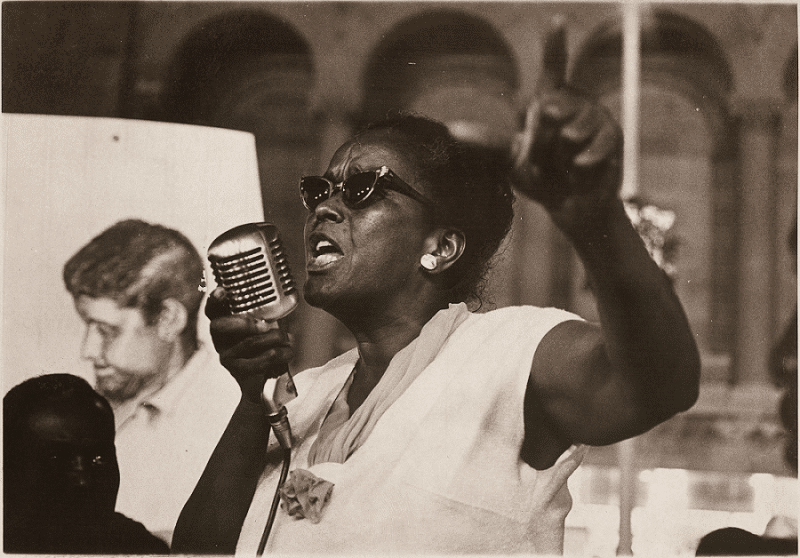

Often remembered as the “Mother of the Civil Rights Movement,” Ella Baker (1903-1986) spent much of her childhood in Littleton, in Halifax County, N.C. Photo by George Ballis. Courtesy, Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture

In these days when we seem to have forgotten who we are, and what is best within us, I have found myself thinking often about the legendary civil rights activist Ella Baker and a spring day two years ago when I visited Littleton, the small town in Halifax County, N.C., where she grew up.

My pilgrimage to Littleton came about because a wonderful local historian, the Rev. Dr. Florine Bell, had offered to give me a tour of some of the local sites that had been important to Ella Baker and her family.

I eagerly accepted her kind invitation. Often remembered today as “The Mother of the Civil Rights Movement,” Baker was raised in Littleton in the 1910s and ‘20s.

She has long been one of my heroines. I had heard many stories about her, and I had read some wonderful books about her, especially Joanne Grant’s Ella Baker: Freedom Bound and Barbara Ransby’s Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement.

And of course, I knew what a historic role she played in the founding of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the civil rights group that emerged out of the student sit-ins in 1960.

After that first gathering at Shaw University, the young activists of SNCC went on to be at the forefront of the struggle for voting rights and racial equality across much of the South.

Baker was always like that: building others up, nourishing local grassroots leaders, making sure that movements for social change were grounded not in charismatic leaders, but in ordinary people, whether they were college students or factory workers, teachers or cotton pickers.

“Strong people don’t need strong leaders,” she famously said.

I knew that much about Ella Baker, but I knew very little about the community that made her who she was— and that gave her the fortitude and moral compass that led her to devote her life to working for civil rights and human rights in America.

I could not have had a better guide to Ella Baker’s life in Littleton than Dr. Bell. Born and raised just outside Littleton, she has lived there in Halifax County all her life.

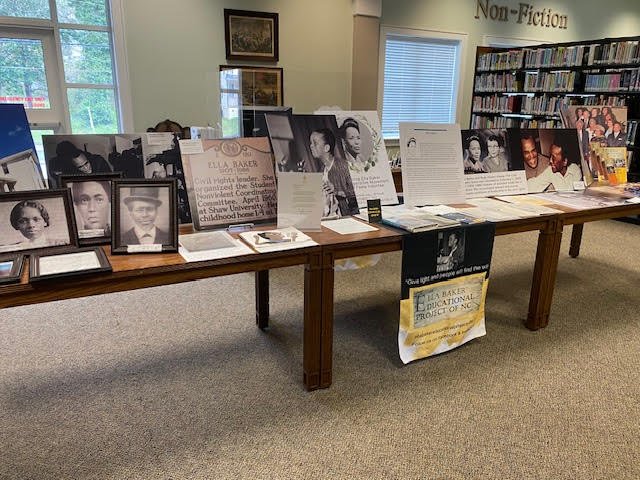

On my way home, I visited the Ella Baker Educational Project of NC’s exhibit on Ella Baker at the Warren County Public Library in Warrenton, N.C. Photo courtesy, the Ella Baker Educational Project of NC

She is a church pastor, a community activist, and a scholar with a master’s in history and a doctorate in theology. Ardently devoted to the region’s history, she has a deep knowledge of Ella Baker’s local roots and her involvement in the African American freedom struggle.

And as you can see in her photograph, Dr. Bell looks out on the world, no matter how broken it is, with a warm and loving smile.

Dr. Florine Bell at our lunch spot in Garyburg, Va. Photo by David Cecelski

The Rev. Dr. Florine Bell is part of a remarkable corps of community volunteers who have accepted the responsibility of being the caretakers of Ella Baker’s legacy in Littleton.

In 2017, they formed a non-profit organization called the Ella Baker Educational Project of NC. Their mission is grounded in this statement, which was at the core of Ella Baker’s beliefs:

“We believe that democracy belongs to the people and that real change starts from the ground up.”

Ella Baker Day

I had never met Dr. Bell before that trip to Littleton, but I had heard her speak once and I had been deeply impressed. That was at Littleton’s first ever “Ella Baker Day” back in 2017.

In her remarks at that gathering, Dr. Bell had observed that visitors from many different parts of the United States had come to Littleton that day to honor Ella Baker’s legacy.

In April 2022, Dr. Bell and other caretakers of Ella Baker’s legacy in Littleton gathered at a dedication of a state highway marker honoring Baker. Ella Baker’s grandniece, Dr. Carolyn Brockington, is on the far left. The marker is located on US 158/903 (Main Street) at East End Ave. Photo courtesy, Roanoke Rapids Daily Herald.

But Dr. Bell also noted that few people here in Baker’s home state seemed to remember her and the central role that she played in America’s civil rights movement.

Even in Littleton, she told the audience, Baker’s memory had faded. Many of the town’s young people had never heard of their hometown’s most famous daughter.

Dr. Bell wanted, she said, to make sure that especially the town’s schoolchildren would know that somebody who changed the world came from right there in Littleton. She wanted them to believe that they could grow up and change the world, too.

On East End Avenue

I met up with Dr. Bell and her husband, David Bell, Sr., in the parking lot at the Methodist church in downtown Littleton.

They greeted me warmly. Dr. Bell gave me a big hug, and David extended a firm handshake. Then we jumped in David’s pickup and headed off.

Dr. Bell and I had already talked on the telephone a couple times, so I had gotten to know her at least a little bit. But I had never talked with David before. I was glad for the chance to get to know him.

I learned that he was from Occoneechee Neck, down in the big bend of the Roanoke River east of Littleton.

He reminded me of some of the men with whom I grew up in a different part of Eastern North Carolina.

He was soft-spoken, kind-hearted and, I could tell, steady as a rock. He had a quiet confidence in his bearing, a passion for hunting and fishing, and a deep feeling for the land and its history.

The first place that Dr. Bell and David took me was Ella Baker’s childhood home on East End Avenue in Littleton.

The simple, two-story frame structure looked as if it was built in the late 19th or early 20thcentury. A member of Baker’s family, her grand-niece Dr. Carolyn Brockington, still owns the house.

When I was there, no historical marker yet identified the house as having been Ella Baker’s home. (That changed just a few months ago.) But that did not matter to me. Dr. Bell’s stories brought the place to life.

David Bell Sr. at the childhood home of Ella Baker in Littleton, N.C. Photo by David Cecelski

We had been given permission to visit the house, so we wandered around the yard while Dr. Bell told stories about Baker’s family and her childhood in Littleton.

Dr. Bell reminded me that Baker’s mother was from a large and prominent African American family that was mainly in Littleton and in Elam, a small town just across the Roanoke River in Virginia.

(I believe one set of her grandparents also had a farm a little to the west of Littleton, in Warren County.)

Ella’s mother Georgiana Ross Baker and her father, Blake Baker, had been living in Norfolk, Virginia, when she was born in 1903.

A few years later, Ella Baker and her mother moved first back to Elam, then to Littleton to be close to the rest of her mother’s family. Her father stayed in Norfolk so he could keep his job there.

Baker attended school in Littleton. She went to church and Sunday school in Littleton. She learned her people’s history in Littleton.

In 1918, Baker left Littleton to attend Shaw University’s high school academy in Raleigh. She finished high school there, then went on to college at Shaw. She graduated as valedictorian of her class in 1927.

Josephine Elizabeth “Bet” Ross

Driving out of Littleton, the Bells next took me to the old plantation where Ella Baker’s grandmother had been born into slavery.

The house is still there, much of the land is still fields, and the old paths still lead down to the Roanoke River.

David Bell Sr., Tom King, and Dr. Bell at the former plantation where Ella Baker’s grandmother Josephine Elizabeth Ross had been enslaved when she was young. Photo by David Cecelski

Ella Baker’s grandmother, Josephine Elizabeth “Bet” Ross, was born on that plantation in 1847.

Elizabeth Ross was an important person in young Ella’s life. In interviews, Baker often recalled how her grandmother’s stories about the horrors of slavery, and the brutality that her grandmother herself had faced, shaped her determination to devote her life to the struggle for civil rights and human rights.

Tom King, who is in the process of restoring the house, had graciously offered to meet us there. He led us through the rooms, sharing what he had learned from the way it was constructed and the materials that were used.

From the windows, we looked out on the fields where Ella Baker’s ancestors had toiled.

Downstairs, we visited a kitchen that was built of large stones and great wooden posts. The house was a couple centuries old, but somehow the kitchen looked even older and more worn.

Dr. Bell in the kitchen of the old house. The house was being restored at that time. Photo by David Cecelski

The Graveyard in the Woods

We next followed a series of backroads that ran down into the deep woods along the Roanoke River. Eventually, we branched off on a dirt road that led to one of the high bluffs next to the river.

There was another old plantation house there, though it did not seem to be in good repair. We parked on the edge of a little glade near the house, and Florine led us into the woods.

On the very edge of the forest, we found a small cluster of gravestones. They marked the resting places of some of the family members who had owned the plantation before Civil War.

After we read the inscriptions on their stones, Dr. Bell drew David and my attention to the surrounding forest. The understory was unusually open, and the ground had a rich covering of ferns and moss.

Dr. Bell told us that it was the site of an old slave cemetery. Using ground penetrating radar, experts had confirmed the presence of the graves. Dr. Bell explained that they were all around us.

There, she pointed, and way over there, and down that way too, she said. None of the graves was marked.

Countless thousands of men, women, and children had once been enslaved along that part of the Roanoke. All along the river, for miles and miles, the woods must hold many other similar graveyards, all but a few unknown and unremembered.

Ebony, Gasburg, and the Old Homeplace

We visited other places that were important in the story of Ella Baker’s family, too.

Crossing Lake Gaston, we drove into the small town of Ebony, Virginia, where we visited the old Mosely Store and post office, one of the places that Baker’s grandfather, the Rev. Mitchell Ross (1827-1908), was often sent to do errands when he was young.

On our way back, we stopped in Gasburg, Virginia, and had a lovely lunch at Pino’s Pizzeria.

While we were there, we talked about all we had seen. Dr. Bell also shared other stories about the region’s history—tales of old river ferries, the building of the dams, and the Revolutionary War.

Then we crossed the lake and headed back toward Littleton. Along the way, David pulled off the road at a little clearing. We got out there, and he and Dr. Bell showed me the ruins of an old homestead.

Baker’s grandmother and grandfather had made their home at that spot in their first years of freedom.

All that was left was a crumbling chimney and the telltale traces of the foundation, but it still felt like a special place.

The chimney is now half-lost in brush and bramble. But I was still glad we were there.

We found some old handmade bricks that had come loose from the chimney and held them in our hands. We wondered who had made them, and if the brick mason had been someone in Ella Baker’s family.

Roanoke Chapel Baptist Church, Littleton, N.C. Photo by David Cecelski

Last of all, we visited the Roanoke Chapel Baptist Church, just a few miles north of Littleton.

Baker’s grandfather, Rev. Mitchell Ross, had founded the church in 1872, only a few years after the Civil War. Ella Baker had attended the church with her grandparents and other members of her family.

In the cemetery, we found, among others, the Rev. Ross’s final resting place, which you can see in the photograph here.

The grave of the Ella Baker’s grandfather, the Rev. Mitchell Ross, Roanoke Chapel Baptist Church, Littleton, N.C. Photo by David Cecelski

The Road Home

We left the churchyard late in the afternoon. It had been a glorious day, but it was time for us to get back home.

Florine and David—we were calling one another by our first names by that time—carried me back to my car in Littleton.

We said our good-byes there, and I told them what a joy it was to spend the day with them.

We made our promises to see one another again soon, and then I got back on Highway 158 and headed home.

All along the way, I re-lived the day in my mind, the splendor of it all, and how much I learned, and how much it means to me, and I think to us all, to have caretakers of history like them.

You can learn more about the Ella Baker Educational Project of NC and its upcoming activities here.

The Project’s volunteers depend on donations to protect and share Ella Baker’s legacy here in North Carolina. If you would like to make a donation in support of their work, you can do so here.

Thank you!!!!Amy Laura Hall919-616-8642

LikeLike