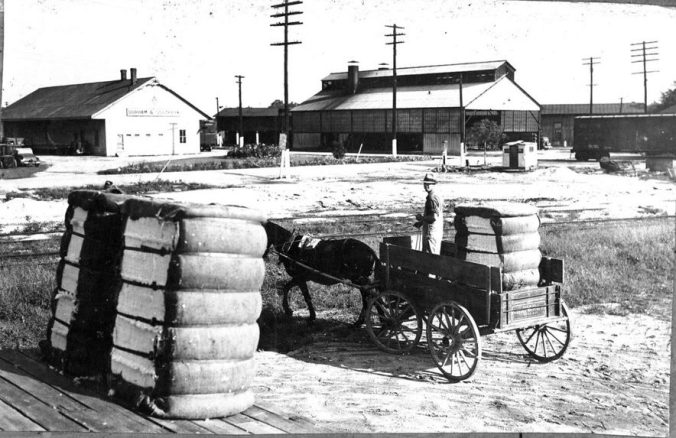

Jesse and Casper Tart’s cotton gin, Dunn, N.C., 1938. State Archives of NC

This is the third photo-essay in my series “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.”

You can find my introduction to the series here.

While documenting factory and farm life in North Carolina, one of the NCDC&D’s photographers went to Dunn, in Harnett County, to take a look at the cotton industry in Eastern North Carolina.

Late in the summer of 1938, when farmers were harvesting their cotton, that photographer visited a cotton gin owned by two local brothers, Jesse and Casper Tart.

Founded by their father in 1905, the Tart brothers’ cotton gin was part of an extensive family enterprise that included a lumber mill, logging interests over a broad swath of both Carolinas, a livestock yard, a farm, a general store, a construction business, and at least two cotton gins.

In those days, cotton really was king, as they used to say, at least in Harnett County: cotton had been by far the largest and most profitable local crop since the county was established in 1855.

In the early 20th century, Dunn was said to be one of the country’s largest cotton wagon markets, with crowds of local farmers and cotton buyers from near and far coming together every summer.

In those years, even the local demand for cotton seemed to have no end, mainly because, in 1904, the Erwin Cotton Mills Company opened a massive cotton mill 10 miles west of Dunn.

The mill– two mills, eventually– formed the heart of a bustling company town called Erwin that was owned and governed by the cotton mill.

Families from farming and fishing communities all over Eastern North Carolina had migrated to Harnett County to work at Erwin Mills. The mill was the first denim maker in the southern states and by the 1920s the town of Erwin was calling itself the “The Denim Capital of the World.”

In those days, a local farmer might grow cotton, his wife and maybe some of his children too might work in the mill, and it was not surprising if he wore overalls made with denim from the mill.

(That was possible at least if the farmer was white; African Americans were not allowed to work at Erwin Mills or any other cotton mill in Eastern North Carolina, except in a small number of especially menial, dirty, or dangerous jobs that were reserved for people of color.)

By the time that this photograph was taken, workers at the two Erwin mills ran more than 64,000 spindles and operated 2,300 looms, turning out prodigious quantities of denim, stripes, and what was called fancy suiting.

A cotton gin such as the Tart brothers’ was one of the many local businesses that were essential to the cotton industry, but were neither farm nor mill. In the countryside around Dunn, farmers brought their cotton crop to the gin to have the cotton fibers separated from the seeds.

The gin’s machinery used a rotating drum with teeth or saws to separate the cotton fibers from the seeds.

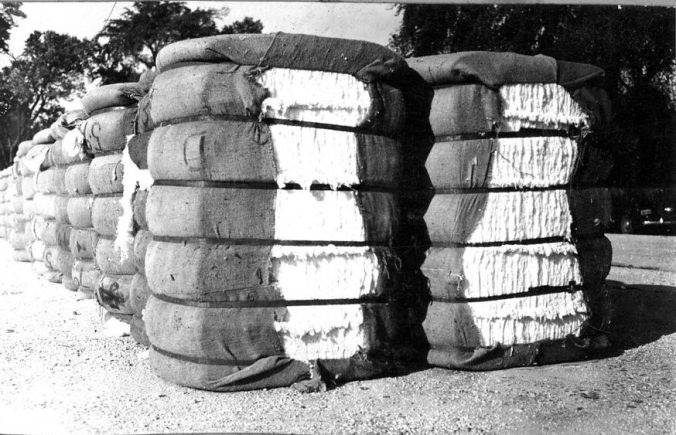

For ease of handling and shipping, the gin’s workers then pressed the cotton into bales using other machinery. Most cotton bales weighed between 500 and 700 pounds.

Cotton bales stacked at the Tart brothers’ gin, Dunn, N.C., 1938. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

By the time these photographs were taken in 1938, cotton’s hold on Harnett County had loosened a good deal.

That trend had begun in the 1920s, following a sharp decline in cotton prices due to overproduction after World War I, a rural recession in the early ’20s, and the spread of the boll weevil.

The move away from cotton heightened during the Great Depression. With the price of cotton so low, many farmers switched to tobacco, which soon replaced cotton as the county’s most important cash crop.

In addition, after the Stock Market Crash of ’29, many of the county’s farmers took acreage out of cotton and turned instead to growing food crops that, at the very least, could help to feed their families.

In their quest to be more self-reliant, many local farmers also began growing more hay and other feed crops. Prior to the Depression, they would have been more likely to have purchased feed from farmers in the western part of the state so that they could plant as much cotton as possible.

Between 1929 and 1932 alone, the amount of land that Harnett County’s farmers had in cotton fell from 45,000 acres to 29,000 acres.

In 1926, the county’s farmers grew only a single acre of tobacco for every ten acres of cotton. A decade later, in 1936, they were growing four acres of tobacco for every ten acres of cotton– and selling the tobacco for a much higher price than the cotton. (Sanford Herald, 14 Sept. 1936)

Many were glad to see cotton go. While great fortunes had been made in cotton, it was a cruel crop for the people who worked in the fields and had to pick it. Most, but hardly all, were African American men, women and children.

Many of them were tenant farmers. In the 1930s, half of Harnett County’s farmers did not own the land on which they farmed and lived. They worked on shares; many saw precious little profit, if any.

Many tenant farmers moved frequently, looking for better land or a more accommodating landlord.

In the 1880s, thousands– maybe tens of thousands– of African American men and women had joined a labor movement led by the Knights of Labor to try to end the almost slavery-like conditions that still existed on Eastern North Carolina’s cotton farms.

(Tellingly, field workers still referred to the region’s larger cotton farms as plantations well into the 20th century.)

Even when these photographs were taken, no crop had more of an association with slavery than cotton, and none did more to drive black families out of Eastern North Carolina.

Nonetheless, even on the eve of World War II, many of Harnett County’s African American citizens– and plenty of others too– had little choice but to work in the cotton fields if they were going to feed their children and make sure they had something decent to wear to school.

There were not a lot of other options in Harnett County, and times were hard: when harvest time came, no matter how hot the sun, no matter how much the thorns tore up their hands, and no matter how little it paid, mothers and fathers rose long before first light.

They’d grab a cooked sweet potato, or maybe a slab of cornbread or a biscuit, douse them with a little sorghum syrup or blackstrap molasses, then head into the cotton fields.

-End-

Next up: “Mending Net at Hatteras, 1939”

Powerful piece. Makes one appreciate the virtues of synthetic fabrics. Really enjoying this series.

LikeLike