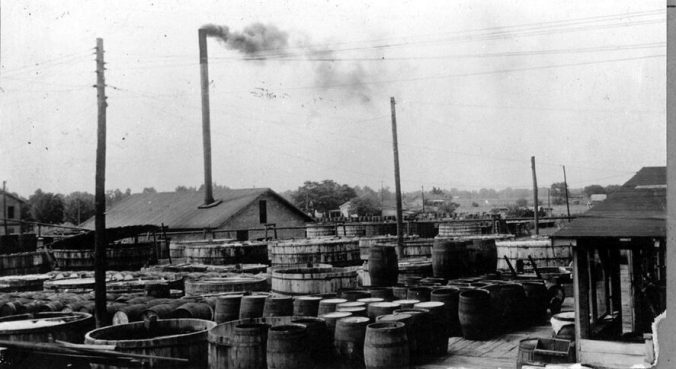

The Charles F. Cates & Sons pickle factory, Faison, N.C., 1941. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

This is the 20th, and penultimate, photo-essay in my series “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.”

You can find my introduction to the series here.

This is the Charles F. Cates & Sons pickle plant in Faison, a small town that straddles the boundary line between Duplin and Sampson County in the eastern part of North Carolina.

The photograph was taken in 1941, a few months before Pearl Harbor.

Founded in a little mill village called Swepsonville, N.C., in 1898, the company relocated to Faison in 1929. Within a few years, the company was buying 50,000 bushels of cucumbers annually and had become the largest independent pickle producer in the United States.

Charles F. Cates, the company’s founder, often said that he was following in the footsteps of his mother. According to family lore, his mother, Elizabeth Bradshaw Cates, had paid for her children’s schooling by making jams, jellies, pickles, and preserves.

Going up and down the streets of Swepsonville, she had sold them out of the back of a farm wagon.

Charles F. Cates & Sons was one of two companies that made that corner of Eastern North Carolina famous for its cucumber and pickles.

The other was of course the Mount Olive Pickle Company, which is still based in Mount Olive, a small town nine miles north of Faison on the border of Duplin and Wayne counties.

The Mount Olive Pickle Co. was the brainchild of a Lebanese immigrant named Shikrey Baddour.

I am not sure, but I presume that Baddour was part of the Maronite Diaspora, a great migration of millions of Maronite Catholics out of Lebanon and Syria in the late 19th and early 20th century.

They scattered across much of the world, but for a time there seemed to be at least a Maronite family or two in every small town in Eastern North Carolina, as well as larger communities of Maronite immigrants in some towns, such as Rocky Mount and New Bern.

My story “Evelyn Zaytoun Farris: Love Stories” focuses on the history of the Maronite communities in New Bern and Rocky Mount. It was part of my “Listening to History” series back in 2004.

According to legend, sometime in the early 1920s Shikrey Baddour drove through Mount Olive and observed the large number of cucumbers that were rotting in the fields for lack of a market to sell them.

On his return to Goldsboro, he set about obtaining the financial backing of two Goldsboro businessmen and setting up a company to buy surplus cucumbers in Mount Olive, brine them, and sell them to pickle companies elsewhere in Eastern North Carolina.

In 1925 and 1926, new investors joined the business, land was purchased in Mount Olive, and the Mount Olive Pickle Co. was created. Baddour remained with the company, but not as its president. Soon the company began marketing its own “Carolina Beauty” brand of pickles.

At the time these photographs were taken, in 1947, the Mount Olive Pickle Co. was still largely a regional company, providing pickles and relishes to retail markets mainly in Virginia, Florida, and the Carolinas.

Still based in Mount Olive today, the company is now one of the largest pickle makers in the U.S. and its pickles and relishes can be found in grocery stores across the country.

Like all the featured photographs in this “Working Lives” series, this image comes from the N.C. Department of Conservation and Development Collection at the North Carolina State Archives in Raleigh.

-2-

Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

For me this is an iconic image of life in Eastern North Carolina in the first years after World War II.

This photograph and all the ones below were taken in Mount Olive two years after the end of the war, in the spring of 1947.

In the photograph, we see two long lines of farmers taking their cucumber crop to market. There are hundreds of farmers. Most have arrived in automobiles hauling trailers, but we can also see that at least a few farmers are sitting in horse-drawn wagons.

The contrast between the automobiles and the farm wagons is what stands out most to me. The scene gives us a glimpse of a world moving boldly into a new age, yet the old ways of doing things have not yet disappeared entirely. Old and the new are all nestled up next to one another.

After the war, there would be greater prosperity, incredible new technology, automobiles everywhere, all kinds of previously unimagined things to buy and places to visit.

For some, it was the dawn of a wonderful new age of abundance, where everything moved fast and you could put the old provincialism of country life behind you.

But for others, and especially many of those who were older, the post-war years often felt as if the whole world had lost its mind and was careening helter-skelter into goodness-knows-what.

On the lefthand side of the photograph, we can see a long line of spanking new electric poles, another sign of the transformation of life that was occurring in those first years after the Second World War.

-3-

Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Our next photograph shows a five-acre cucumber field on the farm of a Mount Olive farmer named O. J. Bundy. According to an article published in the Wilmington Morning Star on July 20, 1947, Bundy was one of the many local farmers that supplied cucumbers to the Mount Olive Pickle Company.

At that time, the company made what are called “advance contracts” with most of its cucumber growers.

Those contracts laid out the terms of an agreement between the company and its growers prior to planting time.

In a typical advance contract, the company committed to providing a farmer with seed, fertilizer, and a guaranteed price for, say, every 100 pounds of cucumbers delivered to its door.

In return, the farmer was committed to planting that specific variety of seed and to follow certain guidelines for growing and harvesting their cucumber crop. In some cases, the contracts even committed farmers to hiring a certain number of field workers per acre.

That way the company could assure that a farmer had adequate labor to harvest their crop in a timely fashion and deliver the cucumbers to the company while they were still fresh.

At times, the company also bought cucumbers at the produce markets in Mount Olive, Faison, and elsewhere.

The field work was hard, hot, and ill paid. Every picker carried a measuring board. If a cucumber was too large for pickling, the worker left it in the field and it probably ended up being fed to the hogs.

-4-

Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

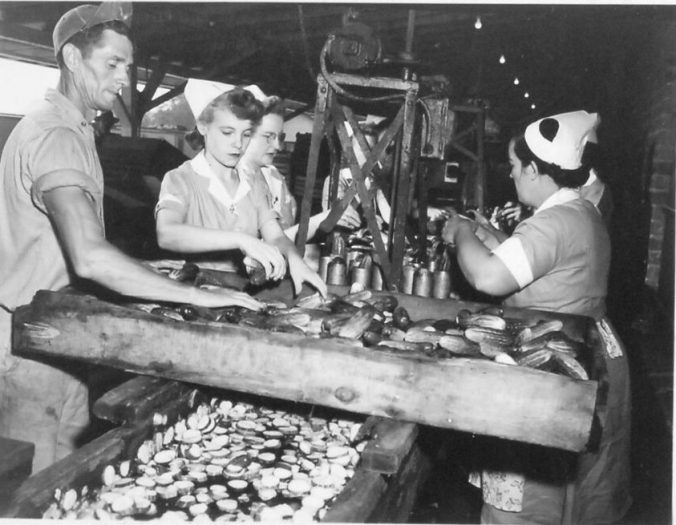

With this photograph, we go inside the Mount Olive Pickle Co.’s plant in Mount Olive, N.C., also in June of 1947.

For all the workers in this photograph, but especially the women, this was almost certainly their first job off the farm.

This group of women and the one man are grading and slicing cucumbers to get them ready for brining. At that time, according to the Wilmington Morning Star’s article, approximately 150 people were employed at the plant.

That article also mentioned that the company had purchased cucumbers from farmers in 23 North Carolina counties that spring.

Then as now, the desired cucumber for pickling was a thin-skinned variety with plenty of warts– always the sign of a fresh, crunchy pickling cucumber, unlike the smooth, thicker-skinned varieties grown for eating in salads.

-5-

Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

At the Mount Olive Pickle Co., a score of brining tanks like this one stood next to the plant’s assembly line.

To make bread and butter pickles, the workers placed the cucumbers in the brine in the morning. By the end of the day, the cukes were ready to be processed, packed, and shipped out.

For other kinds of pickles, the workers sliced them, then trolleyed them outside to the company’s “tank farm.” There they soaked in brine for months, then were brought back into the plant for canning and shipping later in the year.

Only a couple decades earlier, the commercial production of dill pickles had required brining cucumbers for as long as 120 days, the way people had pickled vegetables in their homes for ages.

That changed in the early 20th century.

By the time these photographs were taken, pickle companies had introduced new techniques that replicated the required balance of heat, yeast, and bacteria that had traditionally been left to time and nature.

Using the new techniques, dill pickles still took longer to make than bread and butter pickles, but only an extra day or two.

-6-

Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

A 1929 article in the Goldsboro News (23 June 1929) illustrated how thoroughly scientific innovations and industrial production techniques had transformed commercial pickling in the 18 years between that time and 1947.

In 1929, the Mount Olive Pickle Co. was in a period of rapid growth. In only a few years, the company had grown from pickling 11,000 bushels of cucumbers in a single spring to more than 40,000 bushels.

During peak brining season, the company’s employees regularly worked 10-hour shifts and, to quote a company manager, “were put through the mill.” They worked fast, they rarely had time to take breaks, and the breakneck pace was hard on body and soul.

At that time, company workers produced a total of 52 different varieties of cucumber pickles, with the dill pickles being especially popular in northern cities with large European immigrant communities.

Those were still the years when the process of fermenting the dill pickles was still very much left to nature.

According to the Goldsboro News story from 1929, “cucumbers are soaked in brine from six to 14 months before they are sent through three washings before pickling takes place.”

In this photograph, we see a long row of African American women filling glass jars with pickle slices.

As you may have noticed, both black and white people– mostly women– worked inside the plant, but jobs were segregated by race as were restrooms and break areas. There were even two Christmas parties every year, one for white workers, another for black workers.

-7-

Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

This is the Mount Olive Pickle Co.’s “tank farm,” also in 1947. Over the course of the year, the company’s workers used countless tons of salt to make the pickle brine that was held in the tanks.

The number of cucumbers brined every year was also enormous. According to the Wilmington Morning Star (20 July 1947), the company turned out a total of approximately 750,000,000 cucumbers in 1947.

Workers processed, canned, and shipped a third of those cucumbers immediately. They stored the rest in the saltwater brine contained in these tanks to be processed later in the year.

In that way, the pickle business was not limited to the six weeks a year when cucumbers were ripening in the fields.

-8-

Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

This woman is operating a cap sorter, a deafeningly loud, steam-powered device that turned a jumble of different jar caps until it found the right size, color, and weight for a specific jar.

The cap sorter was the beginning of a 70 ft.-long, porcelain and stainless steel device that jarred and pasteurized the pickles.

-9-

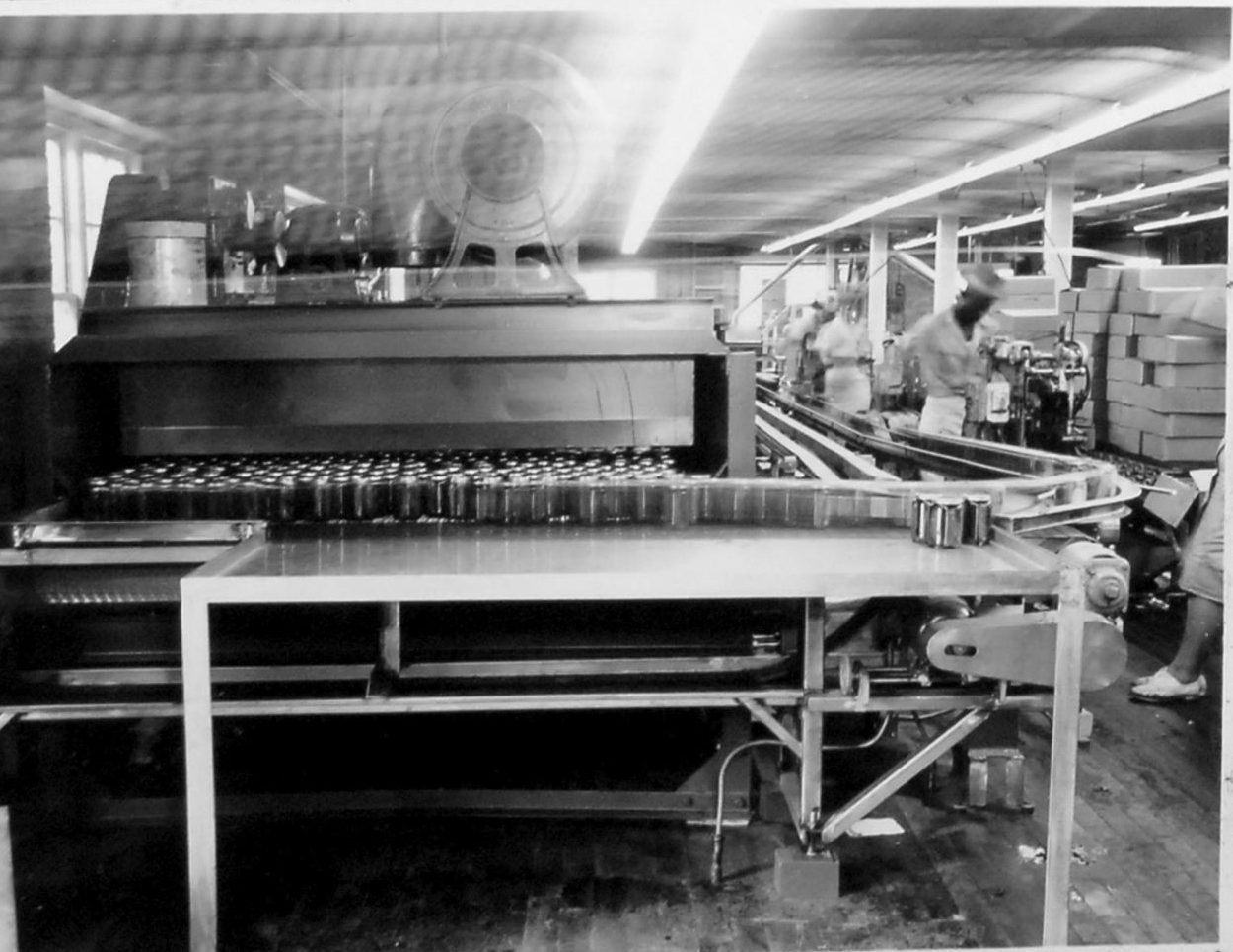

Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

This is the other end of the company’s pasteurizing machine. At this point, the pasteurized jars of pickles came off the conveyor belt and were shuttled over to the machine on the far right, which applied labels to the jars. Workers then boxed up the jars and got them ready for shipment.

The Mount Olive-Faison area was one of the largest pickle producing regions in the United States by the time these photographs were taken in 1947.

However, it was not the only place in Eastern North Carolina that was home to commercial pickle making companies in the first half of the 20th century. Cucumbers grew well in the sandy, loam soils that were found across much of Eastern North Carolina.

As more railroads, and then highways, reached into the region in the early 20th century, pickle companies located plants in at least half a dozen other places in Eastern North Carolina.

Most, but not all of those companies were established by northern businessmen who were immigrants to the U.S.– and especially immigrants from Germany, Austria, and Eastern Europe.

The country’s largest pickle producer, H. J. Heinz, opened a plant in New Bern as early as 1901. The Heinz plant shipped its pickles largely by rail to northern markets with large populations of recent immigrants from Germany, Austria, Russia, Poland, and other parts of Eastern Europe.

Another, smaller pickle company, the Johnson-Earl-Myers Pickle Co., out of Pittsburgh, also opened a branch plant in New Bern in the 1920s, though it did not make it through the Great Depression.

In 1929, an Austrian immigrant, Joseph Orringer, founded the Orringer Pickle Company in New Bern. The company was a fixture on Pasteur Street for nearly 40 years.

Still another business, the C. C. Lang Pickle Co., established a branch plant in Washington, N.C., in 1931. Based in Baltimore, the company was a very large maker of both pickles and sauerkraut.

C. C. Lang opened a second branch plant a few miles to the north in Plymouth and maybe a third in Pinetown, a rural community about a 15 minute drive northeast of Washington.

Another firm, the J. Weller Pickle Co., operating in Wilmington, N.C., in the early 20th century. Based in Cincinnati, the company had been founded in the late 1870s by a former Wilmington resident named Jacob Weller.

A sizable community of German immigrants had settled in Wilmington in the mid-19th century. I haven’t checked, but I would not be surprised if Weller came from one of those immigrant families.

A group of local investors, incorporated as the Carolina Pickle Company, bought out the Weller Co.’s plant in 1929.

-10-

Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

One of the forgotten moments in the Mount Olive Pickle Co.’s history occurred two years before these photographs were taken.

In the last months of the Second World War, the company welcomed 25 young guest workers from the British colony of Barbados to its plant in Mount Olive.

In the spring and summer of 1945, they were part of a group of at least 1,644 guest workers from Barbados that federal agencies placed in U.S. jobs to help relieve a wartime labor shortage.

The large majority of the Barbadians– 1,347 in all– worked in North Carolina. Most were placed in lumber mills and pulpwood plants either in the coastal plain or in mountain communities.

Some of the Barbadian workers were placed elsewhere, however. Those places of employment included brick and tile-making sites in Sanford and Greensboro, farms near Beaufort, N.C., and the Mount Olive Pickle Co.’s plant in Mount Olive.

(See The Robesonian, 8 June 1945; the Goldsboro News-Argus, 9 June 1945; and the Washington Daily News, 12 Sept. 1945).

-11-

Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

This is another view of the long line of farmers bringing their cucumbers to market that we saw in our first photograph.

Note the fine looking horse pulling an African American farmer’s wagon.

When I featured this scene earlier, I discussed what we can see here– above all, the striking mix of old and new, the automobiles and horse-drawn wagons and the new electric lines.

But here I just want to say a few words about what the scene does not and cannot show, but was there.

Only a few years earlier, many of the young farmers in this photograph had left Mount Olive and had gone to war.

They had fought around the world, from North Africa to the Pacific, from Italy to France and Germany.

While they were gone, many of them had seen things, done things, that separated them from those who had never left home.

When I was younger, and more of that generation was still alive, the veterans I interviewed often talked about this.

So too had many of those who had stayed home during the war and who had seen how the war changed their sons and brothers, their husbands and boyfriends, and their old school pals.

It only makes sense. If you were at Anzio or Iwo Jima, or Omaha Beach, or if you had seen what the firebombs did to Dresden, or visited Hiroshima after the bomb fell, or were there when Auschwitz or Treblinka were liberated, you were bound to be a different person.

In talking with the military veterans who came back home, I learned that, in a photograph like this, a farmer might be dressed like other farmers, and a farmer might line up to bring his cucumbers to market like other farmers, but again and again I was told, inside, they were different.

-12-

A young woman displaying samples of different brands of pickles that the Mount Olive Pickle Co. marketed in 1947. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

-End-

David. I hate Cukes. Picked them and carried to market every HS summer Cates contract, bit over an acre. But money meant summer joy at CB.

LikeLike