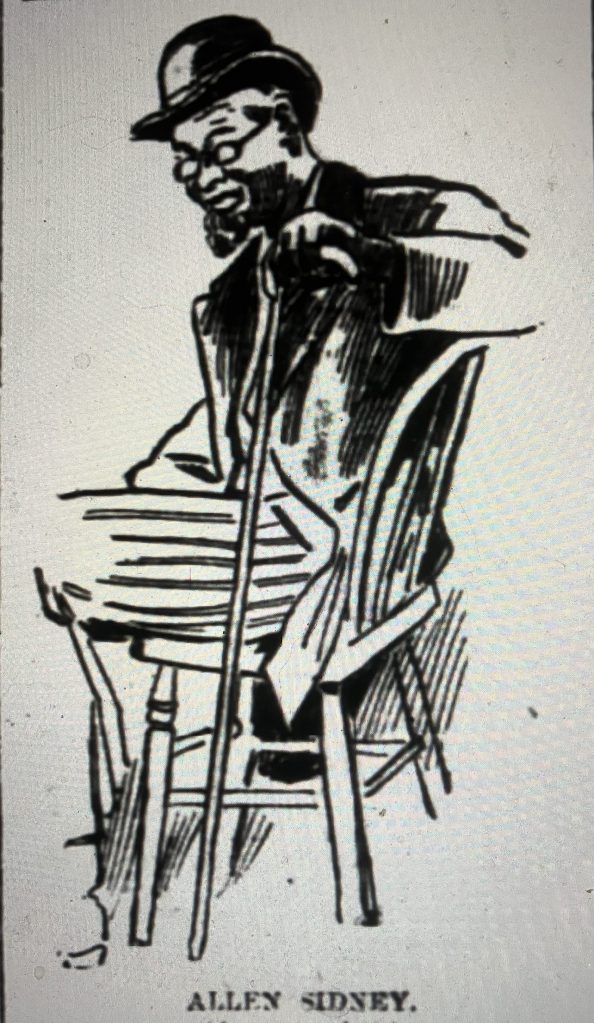

Ink drawing of Allen Sidney. Born enslaved in Edenton, N.C., he was 90 years old and living in Windsor, Ontario, when this drawing was made in 1894. Source: Courier-Journal (Louisville, KY), 12 August 1894.

Allen Sidney was born a slave in the seaport of Edenton, North Carolina, 25 years after the American Revolution.

In or about 1816, he was taken to Western Tennessee. Still a slave laborer, he was made to work for many years as an engineer on steamboats that carried freight on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers.

In 1856, he escaped from one of those steamboats. He crossed the Ohio River and rendezvoused with his wife in Cincinnati. The couple then made their way via the Underground Railroad to Windsor, Ontario, just across the U. S.-Canada border from Detroit.

Four decades later, in 1894, when Sidney was 90 years old, he told the story of his life to a newspaper reporter in Detroit.

Published in a Sunday edition of the Detroit News-Tribune, that article began with a brief introduction, but then allowed Sidney to tell his story in his own words– or at least substantially so.

The newspaper’s editors called the story: “Perils of Escape: Allen Sidney Tells the Story of His Life.”

I never located the News-Tribune’s story, but it was republished in the Courier-Journal in Louisville, Kentucky, on August 12, 1894. That is where I found the portrait of Allen Sidney above. A typescript copy of the story can found in the digital archive of the Ohio History Connection and is available on-line here.

In today’s essay, I would like to reprint Allen Sidney’s account of his life in slavery and his escape to Canada.

Sidney’s description of his youth provides a remarkable look at Edenton in the first decades of the 19th century, but it is very brief. However, he spends far more time describing his life after he had been taken west and had begun his river-boating days.

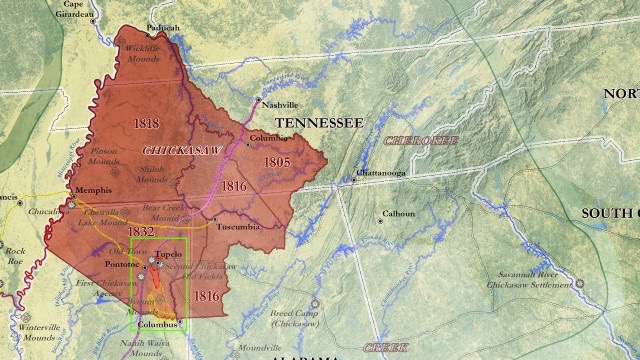

During his early life, white settlers were pushing the Chickasaw and other native peoples out of Western Tennessee and surrounding parts of Kentucky, Alabama, and Mississippi.

As native peoples were dispossessed, white settlers– many of them from North Carolina– moved into their lands. A substantial number of those settlers brought enslaved laborers such as Allen Sidney with them.

I have long wanted to learn more about what became of those who were enslaved on the North Carolina coast (the area I write about) and were then forced to relocate to the lands that were taken from the Chickasaw Nation in Tennessee, Kentucky, Alabama, and Mississippi.

Allen Sidney’s narrative gives us at least one man’s testimony of that experience.

In addition to re-printing the Detroit News-Tribune’s interview with Sidney, I have added illustrations and research notes that I hope will help readers to appreciate his story more fully.

Warning: Allen Sidney’s interview includes a graphic account of torture.

Perils of Escape: Allen Sidney Tells the Story of His Life

Originally published in the Detroit News-Tribune

I was born in Edenton, N.C., on the seashore, in 1804. It was an old shipping port where a good deal of rice and cotton was taken away on ships, and it was also a sort of slave market.

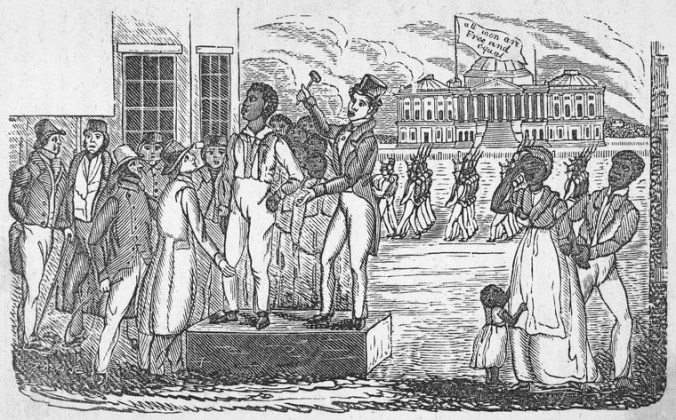

Colored people were run over there from Africa and put into pens, and negro traders came there by the hundreds, bought the slaves and took them West and sold them to the planters.

“A Liverpool Slave Ship.” Oil painting by William Jackson (active 1770-1803), Merseyside Maritime Museum, Liverpool, England. In the 18th century, the large majority of enslaved Africans transported to North Carolina came via other mainland colonies or from the West Indies. However, some slave ships sailed directly from the West African coast to Edenton and other North Carolina ports. For instance, in 1786 the English brig Camden brought 80 Africans directly from the continent of Africa to Edenton. Their story is told in Dorothy Redford’s book Somerset Homecoming, a poignant account of her search to uncover and honor the history of her enslaved ancestors.

When the traders and owners were making bargains, they would feel you all over to see if your muscles were good, look at your teeth and ask what was your age. The buyer would ask your age and the seller would tell the year you were born. I was sold several times, and that is the way I know I was born in 1804.

But I don’t know the day or month.

A 19th-century engraving of a slave auction in South Carolina. From Mrs. A.M. French, Slavery in South Carolina and the Ex-Slaves (1862)

I belonged to Simeon Perry, who was a rich man and owned a good many slaves.

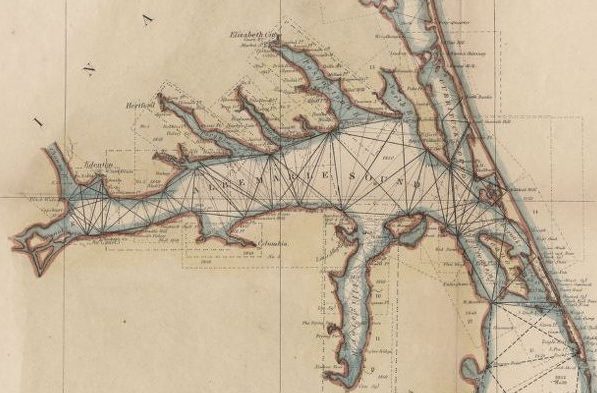

By the late 18th century, the Perrys were a prominent family scattered widely along the north and west side of the Albemarle Sound (above). I have not yet identified Simeon Perry’s place of residence when Sidney Allen was born in 1804, but he is listed as residing in Hertford County, northwest of Edenton, in the 1790 federal census. In that census, he is listed as the head of a large family and as the keeper of eight slave laborers. Map source: U.S. Coast Survey, A. D. Bache, ca. 1852. Courtesy, North Carolina Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill

My father died when I was a small boy and I don’t remember him. He was sitting in his cabin before the fire after a hard day’s work and was sleeping and fell forward into the fire.

He was so severely burned that he died from his injuries.

Harriet Jacobs was born into slavery in Edenton, N.C., somewhere between 9 and 11 years after Allen Sidney. Jacobs escaped from the seaport hidden aboard a sailing vessel in 1842 and went on to write a now-classic narrative of her life that is a remarkable portrait of the town where Sidney spent the first 12 years of his life. Photographer: Gilbert Studios (Washington, DC). Courtesy, Schomburg Center for the Study of Black Culture, New York Public Library

When I was three or four years old, I was put to work. I picked up all the trash on the lawn in front of the house, pulled up the weeds among the flowers and carried water from the spring….

When I got a little older, I scraped cotton– that is, hoed it to keep down the weeds.

My master’s son, Simeon Perry, Jr., got married and my master gave him my brother Dave, my sister Jenny, and me. I was the youngest.

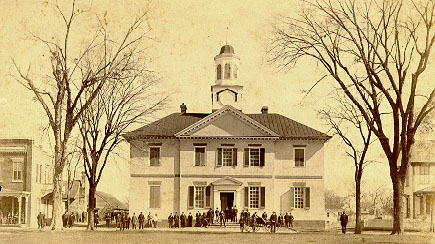

Chowań County Courthouse, Edenton, N.C., 1890. According to a narrative written by Harriet Jacobs’ brother, John Swanson Jacobs, the Chowan County Courthouse was infamous among the town’s enslaved people as a scene of brutality, torture, and public humiliation. A whipping post, stocks, and a pillory were all found on its grounds. Photo courtesy, N.C. Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Young Simeon moved to Tennessee and took me along when I was 12 years of age. I can remember my mother crying as if her heart would break when we were parted.

A common sight in antebellum America: a coffle of slaves bound for Tennessee, ca. 1850. Courtesy, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum

We moved to Lauderdale County and squatted on a farm. They didn’t have to buy land there in those days. Simeon just blazed the trees around 200 or 300 acres and settled on it.

His farm was on the Tennessee River and a lot of planters settled near him.

I am not sure if Allen Sidney was referring to Lauderdale County, Tennessee, or Lauderdale County, Alabama. Both were carved out of the Chickasaw lands ceded to white settlers in the Chickasaw Treaty of 1818, but only Lauderdale County, Alabama, located just south of the Tennessee border, was on the path of the Tennessee River. Evidently, either Sidney misspoke or the Detroit News-Tribune misquoted him. Lauderdale County, Tenn, is located on a river however– the Mississippi– and in the early 1800s, Tennessee law did in some places and some times allow settlers to acquire former Native American lands simply by occupying them and showing that they had improved them over a period of years. Relatively few white settlers acquired land in either Lauderdale County, Tennessee, or Lauderdale County, Alabama, however, until after the signing of the Chickasaw Treaty of 1818. After that time, a land rush of white settlers– including Simeon Perry, Jr.,– moved into the region that had historically been a homeland of the Chickasaw people. Map source: Chickasaw TV Video Network

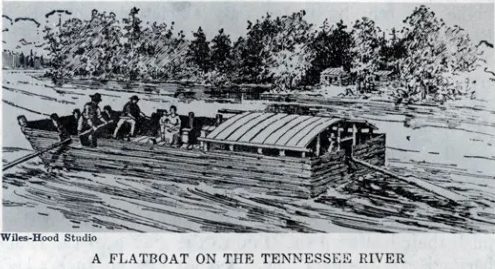

It began to be a shipping place and flatboats were built there, loaded with cotton, corn, and other produce, floated down to the Mississippi and then to New Orleans.

Oil portrait of Andrew Jackson by Rembrandt Peale (1819), Maryland Historical Society. In 1825, Jackson, then a U.S. senator, gave a speech in what had been the Chickasaw lands of Western Tennessee, in which he declared, “To me an inestimable satisfaction is derived from the evidence now offered that the haunts of the Savage man have been exchanged for the cultivated farm.” After Pres. Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Chickasaw were among the approximately 60,000 Native American people forced off their lands and into the Indian Territory that was centered in lands now part of Oklahoma– their forced migration there was the infamous “Trail of Tears.” Source of quote: Emma Inman Williams, Historic Madison; The Story of Jackson and Madison County, Tennessee, from the Prehistoric Moundbuilders to 1917. (Jackson, Miss.: Madison County Historical Society, 1946)

My master was ambitious. He built a flatboat, bought a lot of cattle, wild hogs, apples and truck, went to New Orleans and sold it at a fair profit.

Courtesy, Archives of the City of Kingsport, Kingsport, Tennessee

Then he wanted more capital to do a larger business and borrowed $500 from a planter and negro trader named John Brown and gave me as security.

I was taken to Brown’s place, where he had 400 or 500 slaves. I worked in his cotton fields until next spring, when along came a speculator with 200 or 300 slaves, all chained together.

Catalog for sale of enslaved people from Waverly and Meredith plantations, New Orleans, 13 March 1855. Courtesy, Gilder Lehrman Institute, New York, NY. Between 1830 and the Civil War, New Orleans was one of the nation’s largest slave markets, largely buying enslaved people from the Chesapeake Bay and Upper South and re-selling them to cotton, sugar cane, and other planters in the Deep South. I have not yet identified a prominent slave trader named John Brown in New Orleans. I have also not yet identified the “Capt. Pryor” to which Allen Sidney refers below, though a Pryor family genealogist familiar with Sidney’s account has speculated that he might have been a Mississippi River pilot named Joseph E. Pryor.

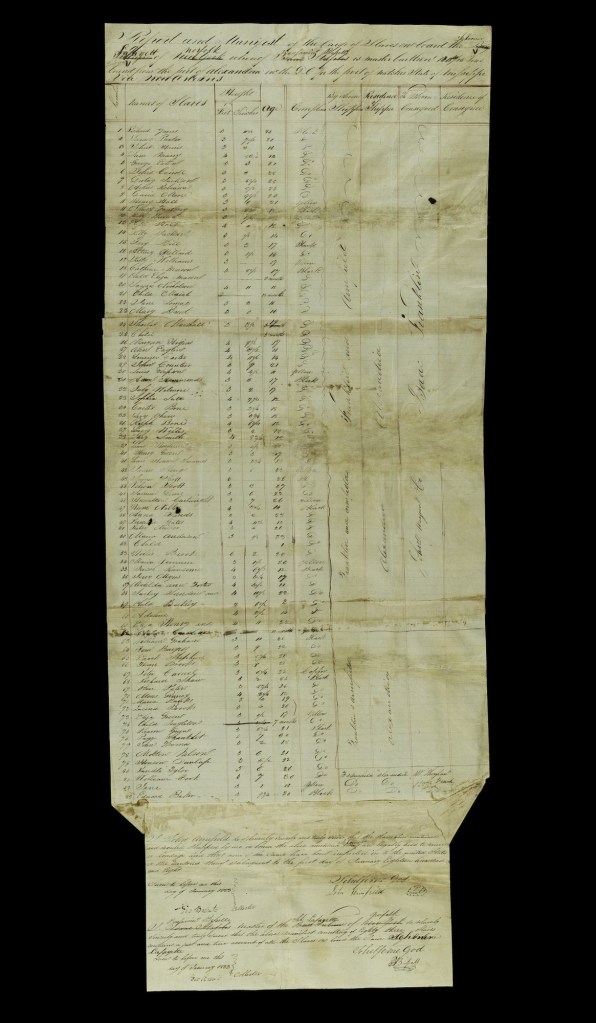

Brown bought the whole lot, and next morning I was chained with the rest and we were marched to Memphis, Tenn., some 400 miles through the Chickasaw Nation.

At the time that Allen Sidney was forced to work in the cotton fields, he was probably enslaved on a plantation near New Orleans– the city is 400 miles south of Memphis and the main overland routes between the two passed through the Chickasaw Nation. In those years, cotton was the backbone of the American economy. It made up more than half of all U.S. exports, undergirded the Industrial Revolution in New England and Great Britain, and played a central role in transforming New York City into a capital of world finance. To supply the workforce on cotton plantations, planters and slave traders sent more than a million and half enslaved people from the Upper South to the Deep South. Many of those enslaved laborers were marched south from states such as Virginia and North Carolina. Others, such as Allen Sidney, also came from the Upper South, but arrived in the Deep South via more indirect paths. Still others were transported south on sailing vessels, including the 83 enslaved people listed on this manifest for the schooner Lafayette. The manifest is for a passage from Alexandria, Va., to Nachez, Mississippi, in 1833. Source: Smithsonian Museum of American History

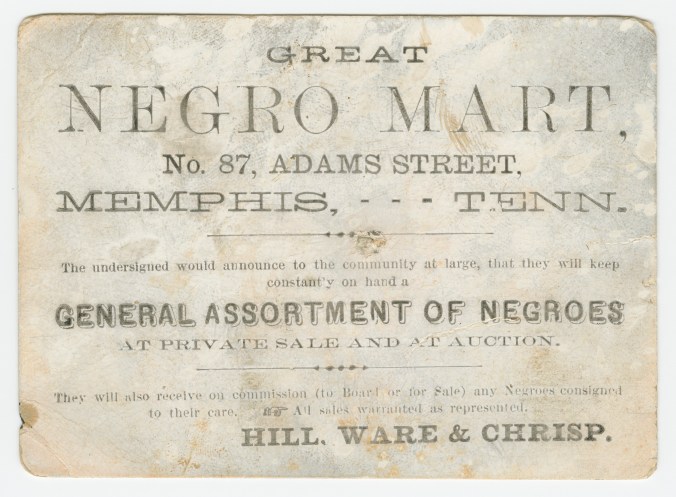

Here Brown sold me with other slaves to a rich man named Capt. Pryor, who lived in Memphis and owned a big farm nine miles out of the city.

Trade card for the “Great Negro Mart” at 87 Adams Street in Memphis, Tenn., 1859-60. The slave trading district of Memphis could not rival the size of the one in New Orleans, but was still very large and very busy by the 1850s. Hill, Ware & Chrisp, the Great Negro Mart’s owners, bought and sold more than a thousand slaves a year. At that time, Memphis’s waterfront was a hectic sprawl of slave pens and auction houses, largely buying enslaved laborers from nearby, Upper South states and selling them south to work in the cotton and sugar cane fields of Louisiana and Mississippi. In the years just before the Civil War, one of the city’s leading slave traders was Nathaniel Bedford Forest, who later became a famous Confederate general remembered today for his role in the massacre of African American Union soldiers at Fort Pillow and, after the war, for serving as the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

In 1825, when I was 21 years of age, Capt. Pryor bought a steamboat at Pittsburgh and brought it down to Memphis.

I believe it was the first steamboat on the Lower Mississippi. It was called the Hard Times.

The first steamboat to operate on the Mississippi River was built in Pittsburgh, but it was named the New Orleans, not the Hard Times. Built by Robert Fulton, the New Orleans was launched in Dec. 1811 and first reached New Orleans early in 1812. Image source: Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory (1856)

I was what was called a “likely boy,” and he thought a good deal of me.

He said to me, “Allen, you go to Memphis. Go on the steamer and watch her.”

So I went there and stayed on her night and day. Then he sent north and got an engineer named Parker, and he ran the boat that winter back and forth between New Orleans [and Memphis].

I helped Parker, and by Capt. Pryor’s orders he showed me how to work the engine.

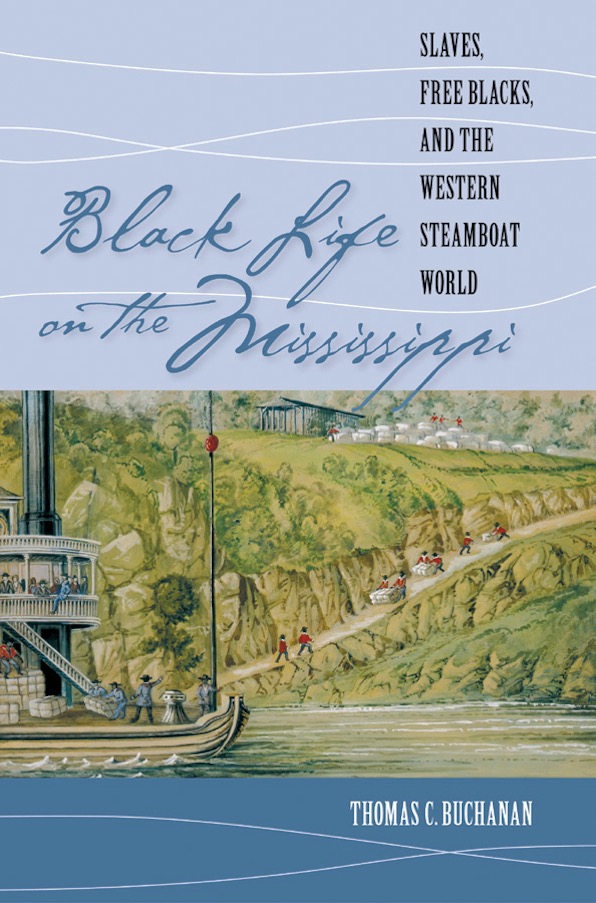

Apprenticing as a steamboat engineer, Allen Sidney was entering a sprawling society of African American maritime laborers who worked on and around the Mississippi River. In Black Life on the Mississippi: Slaves, Free Blacks, and the Western Steamboat World (UNC Press, 2007), historian Thomas C. Buchanan chronicles the history of those black watermen and women, including their central role in the Underground Railroad.

After running on the river that winter, Capt. Pryor built a machine shop in Memphis, put Parker in charge of it, and I worked under him there. I was on the boat in winter and in the machine shop in summer for seven years.

No, I cannot say I was much abused when I was slave, but I have seen many slaves treated very cruelly.

One time, two of Capt. Pryor’s slaves ran away. He took bloodhounds and hunted them down.

When they were brought back to the plantation, they were stripped naked and tied to logs face down. The colored overseer gave them 100 lashes on the back, each stroke being the same as nine, for there were that many thongs on the whip.

Then, with their flesh cut and bleeding, a bucket of salt and water was brought and the overseer dipped a broom in the brine and swabbed their backs.

That was the usual punishment for runaways.

Then they were taken to the blacksmith’s shop and bell and horns put on them. That was an iron collar riveted around the neck and from posts fixed at each shoulder.

Allen Sidney was referring to an iron slave collar and bells like this one that was on display at the Bullock Museum in Austin, Texas. It was part of a traveling exhibition called “Purchased Lives: The American Slave Trade from 1808 to 1865,” produced by The Historic New Orleans Collection.

At the top of the posts, which were about three feet high, a cow bell was hung, which rang every time they moved, asleep or awake. This horn and bell they would wear for three months.

Three months afterward, Perry fixed it all up and came back with papers which he showed to Capt. Pryor.

I went away with him and found that he had moved to a little town called Amsterdam, Tennessee.

The only Amsterdam that I could find anywhere near Memphis was Amsterdam, Mississippi, a long-gone town 230 miles south of Memphis. Located on the Big Black River and at least one stagecoach route, that Amsterdam was only large enough to warrant a post office from 1832 to 1839. Advertisement from the Vicksburg Whig, 7 March 1838.

He had been unfortunate and had sold my brother and sister and had been compelled to work himself– a thing no Southern white man does unless he is very hard up.

I do not know if Allen Sidney ever met or heard from his brother Dave or sister Jenny again. After the Civil War, many former slaves went to great lengths to locate loved ones from whom they had been separated, but the odds of finding individuals taken from the Upper South and transported to the Deep South were not good. To find one another, former slaves sometimes placed advertisements in newspapers, especially those published by national church groups, such as this one that appeared in the Southwestern Christian Advocate on February 1, 1883. For more on this subject, see my essay “I Desire to Find My Children.”

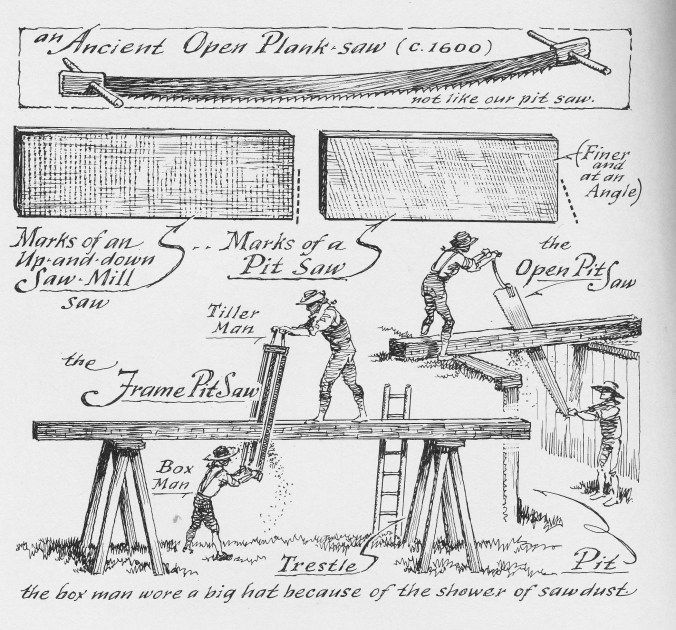

I was the only slave he had, and he supported himself by taking contracts for lumber. There were no sawmills then, and we sawed the logs ourselves with a long saw, he on top and I below, in the old style.

Allen Sidney is referring to his and Simeon Perry, Jr.’s use of a “pit-saw,” a very slow and laborious way of cutting planks that was widely used before the advent of steam-powered sawmills. In many cases, sawyers dug an actual pit into the ground (hence the name). One person stood in the pit and pushed up on the saw, while the other pushed down on the saw from above. You can always identify boards cut by a pit-saw by the up-and-down marks on them. This illustration comes from Eric Sloane’s Museum of Early American Tools (1964)

He had a sister who lived in Kentucky. She wrote letters to him, and he finally moved there, taking me with him.

He settled in Newport, Kentucky and took contracts for chopping wood. But I was too valuable a man to do that kind of work, and he hired me out to the owner of a steamboat as an engineer at $100 a month.

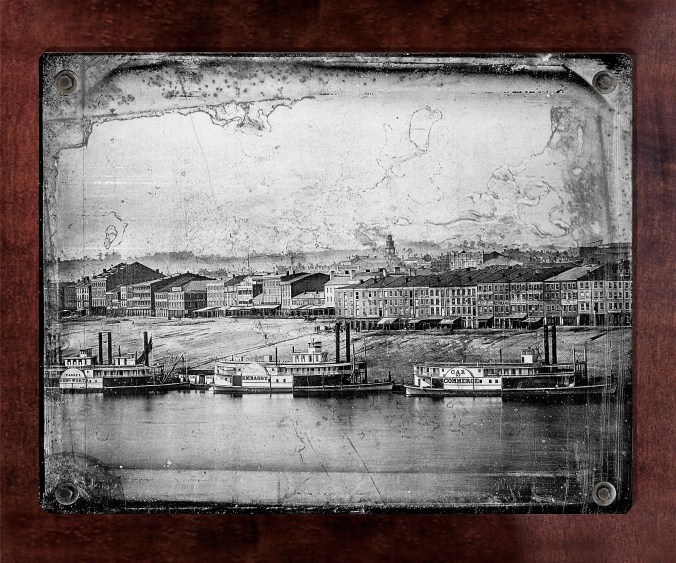

Daguerreotype of steamboats docked at Cincinnati, Ohio, as seen from Newport, Kentucky, 1848. Daguerreotypes had been invented in 1839 and this image is part of what is believed to be the earliest panorama of any American city. Photographers: Charles Fontayne and William S. Porter. For those who were enslaved in Kentucky, the Ohio River, seen here, was the distance between slavery and freedom. Courtesy, Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library

I was engineer of a boat on the Ohio and Mississippi, running between Pittsburgh and New Orleans, until I ran away.

Sometimes the boat lay in Cincinnati for two or three weeks, and I was over the river a good deal.

I fell in love with of a servant of Mr. Gage in Covington, which is also across the river from Cincinnati.

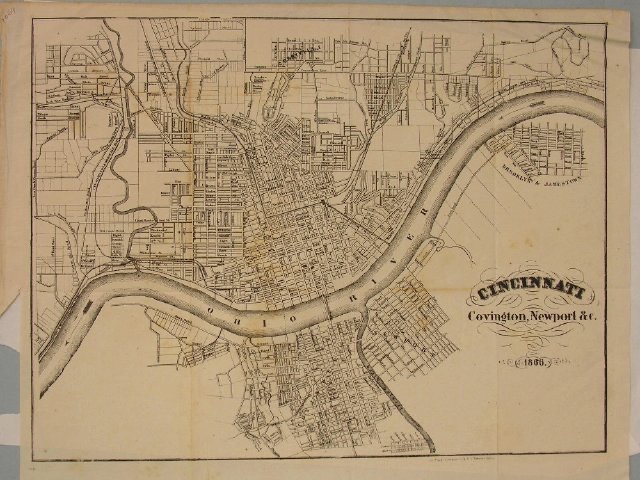

Allen Sidney’s “Mr. Gage” was almost certainly Elisha Gedge or one of his four sons, all of whom were prominent merchants in Covington, Kentucky, before the Civil War. As we will see below, Sidney’s narrative later identifies “Mr. Gage” as a small tobacco manufacturer and storekeeper, both of which were the case with the Gedge family. On this map, dated some years after Allen Sidney and Sarah’s marriage, we can see Cincinnati on the north side of the Ohio River, as well as Newport and Covington, Kentucky, on the south side of the river. The two Kentucky towns are divided by the Licking River, which flows into the Ohio River from the south. Covington is to the west of the Licking River, Newport to the east. Map, Cincinnati, Covington and Newport” (1866). From Appleton’s Handbook of American Travel (New York, 1867). Courtesy, Kentucky Historical Society

We wanted to get married and I got the consent of my master. Then I went to Mr. Gage and said, “I want your Sarah for my wife.”

“Yes,” he said, “if Sarah is willing. When do you want to be married?”

“On Sunday,” said I.

“Well, you can have her then, and I will marry you.”

So we both came into his parlor, and he asked each of us if we wanted to marry, and we said yes, and he said, “You are married.”

There was no minister.

Of course, I had enough to eat, and so had my wife, who remained at Mr. Gage’s house, but I was dissatisfied.

Here was a man taking all my wages and giving me only my board and clothes.

I had some talk with an abolitionist named Tom Dorm, a tall, heavy-set man, with fair hair, who lived in Walnut Hills, a suburb of Cincinnati.

Print showing a view of Cincinnati from the north, 1841 (Klauprech & Menzel). We can see the Miami & Erie Canal in the foreground, the Ohio River beyond it, and, on the other side of the river, Kentucky. In large part because of the steamboat trade, Cincinnati was one of the largest and fastest-growing cities in the U.S. at that time. Because of its location, it had a sizable African American population that had largely come there from the South and played a central role in the city’s Underground Railroad. Though in a Free State, racial tensions were often high in antebellum Cincinnati: anti-black riots scarred the city in 1829 and 1841. Those riots were among the worst in American history and led to the migration of thousands of the city’s African American residents. As was the case with Allen Sidney and his wife, many chose to leave the United States and go to Canada. I have not identified a “Tom Durm” among the city’s leaders of the Underground Railroad. The closest I have come is the Doram family– especially a married couple named Thomas and Jane Doram and their sister-in-law Catherine “Kitty” Doram, all of whom were prominent local African American business owners and conductors on the Underground Railroad.

He came on board the boat at Cincinnati and after a little talk said, “Are you a slave?”

“Yes.”

“Well, I am a friend to all the colored people. How long have you been here?”

I told him.

“Did you ever hear of a place called Canada?’

“Yes, I think I have heard of it.”

“That’s a free country. When you get there, you are as free as I am here. Does your boat run to Pittsburgh?”

I said it did, and also told him [when] it would be there.

“Well, I will send you a notice there, and when you get to Pittsburgh, you will get it,” said he.

He left me with my mind all in a whirl. I went to my wife, who was a cook, and talked about running away. But she objected, saying that Mr. Gage and his wife had treated her very well and Canada, she had heard, was a poor country, where they couldn’t raise anything but black-eyed peas.

When the boat came to Pittsburgh, an abolitionist came on board and talked to me in the same way as Dorm did.

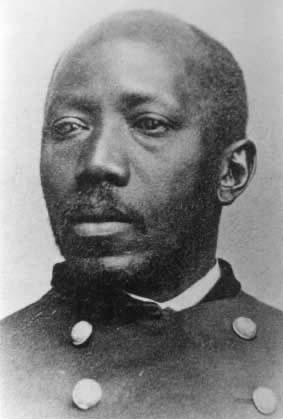

For many years, one of the best-known abolitionists in Pittsburgh was Dr. Martin Delaney (1812-1885), a physician, journalist, Union army officer, and ardent anti-slavery activist who is remembered today as one of the pioneering figures in the history of Black Nationalism. Delaney began publishing a black-controlled newspaper called The Mystery in Pittsburgh in 1843. Later that same year, he and Frederick Douglass teamed up to found the North Star, one of the country’s most important abolitionist newspapers. Photograph courtesy, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library

I said I would like to be free, but my wife wouldn’t go and I wouldn’t leave her. I often talked with her and Dorm and tried to persuade my wife, but it was two years before I got her to consent.

We had two children, William David and Corriller.

The reason she changed her mind was this: Mr. Gage was a small tobacco manufacturer and also ran a dry goods store at Covington. He became embarrassed in his business and said to his wife, “I don’t know but what I will have to sell Corriller to pay my debts.”

My wife heard him.

Next time when I came to Mr. Gage’s house, my wife told me. She was scared and excited, and she said, “O my Lord, if you can, get us away.”

Next time Dorm came down to the boat, I said, “I am ready to go. My wife’s in the notion now.”

He looked pleased and he said, “Now I will tell you what to do. She must keep quiet and say nothing. You go on the boat to Pittsburgh. Before you go, tell your wife to go to Gage and ask his permission to go to church on Sunday night a week with the children. When she gets out of the house, let her go down to the river bank at the back of the house, and we will be waiting there at seven o’clock.”

I did as I was told and so did my wife. There was a boat waiting there, and Sarah and the two children went on board and the boat went to the other side of the river.

When I got to Pittsburgh, I saw the other abolitionist and I left the boat. He had a one-horse wagon filled with straw, and I got under the straw. The bottom had openings, and I got plenty of air.

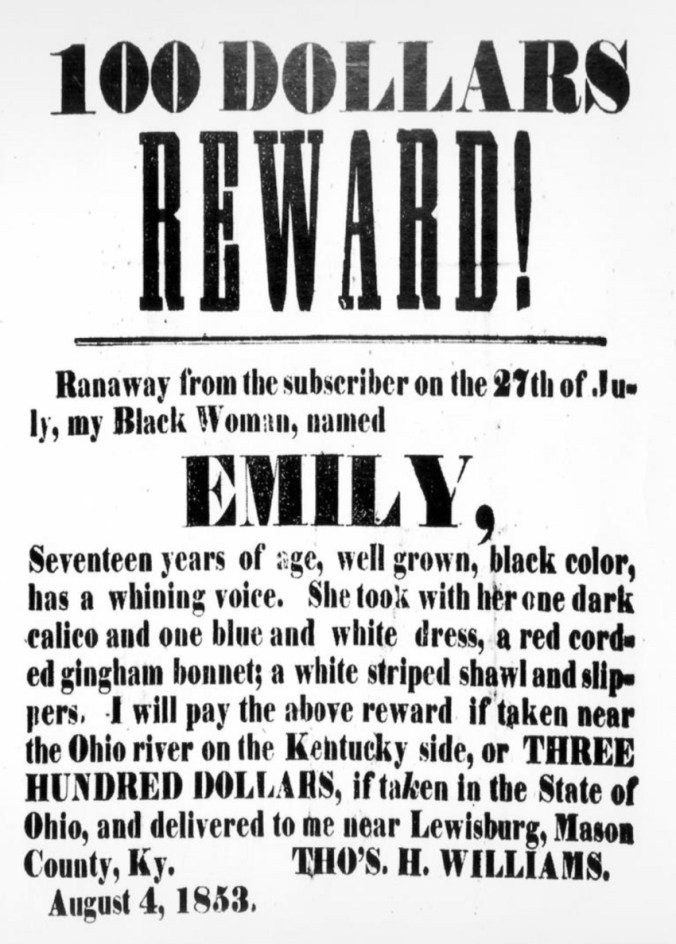

Allen Sidney probably crossed the Ohio River early in 1856. Ohio was a “Free State,” but as we can see in this reward notice for a slave named Emily 3 years earlier, reaching Ohio did not mean that he was out of danger. Especially after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, neither federal law nor bounty hunters acknowledged his freedom anywhere in the United States. For that reason, the caution of the Underground Railroad agents who transported him from Pittsburgh to Cincinnati was quite warranted. Source: Ohio History Connection

We set out for Cincinnati, and I traveled ten nights under the straw and stopped in the daytime in the barns or attics of friendly farmers.

When we got to Cincinnati, I was taken to a little house on Walnut Hills, where my wife and children were hidden.

From there we took the underground route to Canada.

-End-

The Tower of Freedom Monument in Windsor, Ontario, commemorates those enslaved people like Allen Sidney who escaped from the U.S. and settled in Windsor. A sister monument, showing fugitive slaves waiting for passage to Windsor, is on the other side of the Detroit River in Detroit, Michigan. Photo courtesy Lost with Luis

Afterword

That is the end of the interview with Allen Sidney that first appeared in the Detroit News-Tribune in the summer of 1894, then was republished in Louisville’s Courier-Journal.

According to a brief preamble to that story, Allen and Sarah Sidney and their two children crossed the U.S.-Canada Border and arrived in Windsor, Ontario, on April 2, 1856.

That preamble also indicated that Allen Sidney had resided in Windsor ever since that day.

After the Civil War, he made his living by working as an engineer at Frost’s Wooden Ware Works, a manufacturing company in Detroit.

Evidently taking a ferry back and forth across the river, he worked at the company for a total of 37 years.

When the News-Tribune’s reporter interviewed him, Sidney was living with his daughter Corriller and her children in a two-story home on McDougall Street in Windsor. Sarah had passed away a few years earlier.

McDougall Street, where Allen Sidney and his family lived, was the heart of Windsor’s African American community from the 19th century until the 1960s. Today Windsor celebrates the history of the “McDougall Street Corridor” with murals, community events and a walking tour. Photo by Jennifer La Grassa/CBC

The reporter noted that the family was living “in comfort,” and he observed that Allen Sidney’s memory was as “bright and retentive as ever.”

The reporter also said that Sidney was still spry enough to work in his garden.

I have not yet identified the date of Allen Sidney’s death. However, in the March 8, 1898 edition of the Windsor Times, I found this note in the paper’s coverage of provincial elections:

“Sidney Allen, a colored man, nearing 100 years of age, was out this morning and cast his vote.”

The writer went on to say, with a degree of understatement that he could not possibly have appreciated at the time, “Allen is able to fix his age by certain incidents in American history.”

-End-

As always, thank you for your time and excellent research.

LikeLike

Good one David.

LikeLike