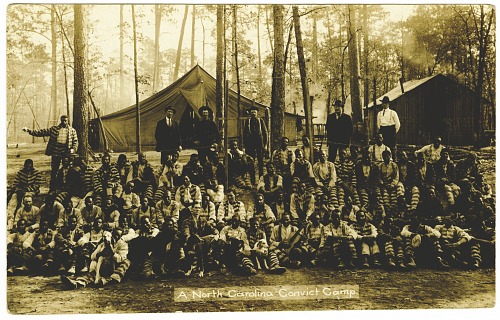

As I looked through the historical collections at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, I also found another important artifact from eastern North Carolina: a postcard, dated ca. 1910, of a convict labor camp in Laurinburg, N.C.

Courtesy, National Museum of African American History & Culture

On the back of the postcard, handwritten script describes the scene as “70 convicts/6 dogs/5 guards/4 white convicts.”

This is an important image for understanding our history.

After the Civil War, a large majority of the state’s prisoners were African American. That was not an accident and it had little to do with criminality: state political leaders openly justified prison construction and convict labor by referring to the end of slavery and calling for new ways to maintain control over a black labor force.

African Americans often ended up on the chain gang for a decade or more for crimes as minor as vagrancy, loitering and petty theft.

In the last decades of the 19th century, prison officials “leased” most of those African American convict laborers to private companies to build railroads and canals. Many also built government buildings.

Convict laborers from Central Prison in Raleigh, for instance, dug many of the canals and ditches that drained the swamps in the vicinity of Lake Mattamuskeet, in coastal Hyde County.

More convict laborers built railroads.

In North Carolina’s mountains, railroad construction involved blasting tunnels, scaling ridges and bridging rivers and was especially dangerous.

In one three-year period, at least 10 convicts leased to the Western North Carolina Railroad died in accidents. During that time, another 22 convicts leased to that railroad died of pneumonia and 17 more succumbed to tuberculosis.

They lived in camps such as the one on this postcard.

According to historian Mathew J. Mancini, the author of One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866–1928, “North Carolina’s nineteenth-century rail network was largely an achievement of convict labor.”

The Good Roads State

By the time of this postcard, most of North Carolina’s convict laborers, of all races, were no longer building railroads or digging canals. Instead, they were building roads and working on state-owned farms.

Convict labor built many of the roads that gave North Carolina its reputation as the “Good Roads State” in the early 1900s.

In 1900 a Report from the Industrial Commission on Prison Labor touted the state’s leadership in using convict labor to build roads. The report marveled that the state could build roads for as little as $800 a mile and was able “to guard, shelter, clothe, and feed convicts for 21 cents a day.”

In 1915 a state official estimated that one-third of the state’s budget for road building crews went to chain gangs.

By that time, many convict laborers also worked on state farms. The largest state-owned prison farm, Caledonia, ranged over more than 4,000 acres in Halifax County, on the Roanoke River.

Before the Civil War, Caledonia had been the site of a large plantation and its owner had enslaved hundreds of African American men, women and children and forced them to raise crops for him.

Only a few years ago I heard a former inmate from Caledonia refer to the prison as “the plantation.”

Convict Cages

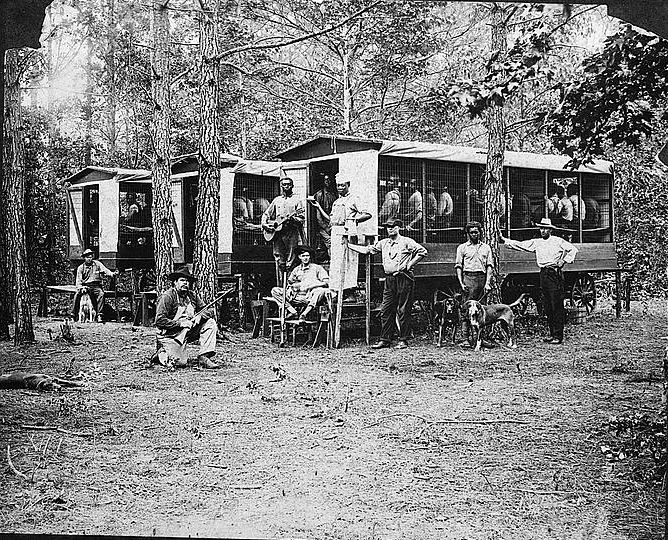

This postcard reminds me of another image from eastern North Carolina that, after first seeing it at the Library of Congress some years ago, I have never been able to get out of my head.

In this photograph, we see a convict chain gang that built roads in Pitt County in the fall of 1910.

Courtesy, Library of Congress

The inmates lived for years at a time in those trailers, which were called “convict cages” and towed from work site to work site.

Note the guitar player on the steps of the closest cage. Note, too, how small they are: a typical convict cage held more than 20 men.

Note also the bloodhounds, which Joseph McLawhorn and his assistants used to track convicts when they tried to escape. McLawhorn, the county superintendent of convict labor, is apparently the man standing just to the left of the two bloodhounds in the foreground.

Six years later, in the winter of 1916, one of the convicts in those cages killed McLawhorn with an ice pick.

Thanks for this article. I have found my white greatuncle in one of those convict camps working on roads in NC in the 1910 census (Township 5, Cabarrus, North Carolina, USA). The majority of the other convicts were indeed black.

LikeLiked by 1 person