Downtown Durham, NC, November 2020.

Ten years ago, a professor at Davidson College, John W. Wertheimer, wrote a fascinating book called Law and Society in the South: A History of North Carolina Court Cases. The book looks closely at eight historic legal disputes that shaped North Carolina in pivotal ways.

One of those case studies chronicled the history of an extraordinary grassroots legal struggle for African American voting rights in the 1950s. Led by an African American attorney named James R. Walker, Jr., the campaign focused on overcoming the historic use of the state’s literacy test to keep black citizens from voting.

James R. Walker, Jr.’s portrait in the 1952 UNC yearbook.

A native of Ahoskie, in Hertford County, N.C., Walker was one of the first two African Americans to earn a degree of any kind from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Following a federal court order, he won admission to the UNC School of Law and graduated in 1952.

Several years after graduating from UNC, Walker made his home in Weldon, a small town 90 miles northeast of Raleigh in Halifax County, N.C. At the time he was the only African American attorney in a six-county, majority-black area.

Walker did not have the support of any state or national-level civil rights group. He also had no experience in civil rights litigation. But he was brash, courageous and relentless: a veteran of the Second World War and a man of great faith (he was also a minister), he waged a relentless campaign against the literacy test and voter suppression in a large swath of North Carolina’s Black Belt.

The term “Black Belt” refers to the group of counties in the southern states that have a majority-black population. In the 1950s, the state’s Black Belt included 11 counties in eastern North Carolina, including Halifax and a cluster of seven other counties along the Virginia-N.C. border.

Since 1900, African Americans in those counties had had little or no access to the ballot box.

Summer of the Red Shirts

If you read my essay “Summer of the Red Shirts,” you know what happened in 1900: self-proclaimed white supremacists successfully waged a statewide campaign of violence and electoral fraud to pass a state constitutional amendment that effectively banned African Americans from voting.

That constitutional amendment provided a legal foundation for whites-only elections and whites-only government in North Carolina for more than half a century.

By the time that James R. Walker, Jr., moved to Halifax County, African Americans in the northeastern Black Belt counties had made some progress in registering to vote. But even as late as 1960, only 16.4 percent of the region’s black citizens were registered voters.

In 1960, a 60-year-old African American in those counties would not have ever known a single person of their own race on a school board, county commission or town council—even though members of his or her race had always made up the large majority of the region’s population.

Similarly, that 60-year-old black citizen would never have known a time when a member of his or her race served in the state legislature, at any level of the judiciary or in any role in the running of local elections.

A History of Voting Rights

Beginning immediately after the Civil War, North Carolina’s white political leaders used many different methods to suppress African American voting rights.

Some of those ways will sound very familiar. For instance, state and local leaders used discriminatory voter ID laws to weed out black voters as early as the 1880s.

Demanding written proof of a former enslaved person’s birthdate was typical: no person born in slavery, after all, had either a birth certificate or other official record of their birth.

In the late 19th century, white leaders suppressed the black vote in many other ways as well—purging voter registration rolls, closing polling places in black neighborhoods, gerrymandering voting districts and a great deal of outright electoral fraud.

The outright electoral fraud included unfairly challenging the eligibility of black voters, failing to count black votes, vote buying and throwing out ballot boxes in black-majority precincts.

(To see a notorious example of electoral fraud in 1898, see my story “Wilmington in 1898: William Price Bell’s Notebooks.”)

North Carolina was also one of the last states in the U.S. to require the use of the secret ballot. Until 1929 voting here was not secret, which meant that African Americans that did succeed in registering and dared to vote against the will of local white political leaders were at risk of being terrorized, fired, evicted and/or retaliated against in some other way.

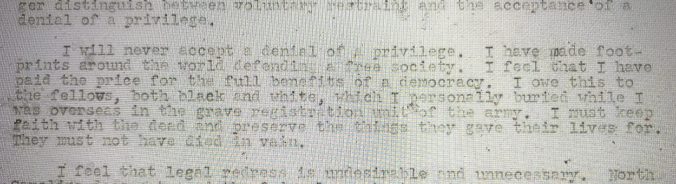

This is an excerpt from a letter that Walker wrote to UNC chancellor Robert House on Jan. 31, 1952, while he was enrolled in the university’s law school. In addressing the racial segregation of social activities on campus, Walker drew on his experience as a WWII veteran to argue for democracy at home. The letter gives a good sense of his determination, passion and eloquence. Courtesy, University Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Mass Incarceration

Over the generations, white extremists in North Carolina also used a great deal of violence to suppress black voting.

Immediately after the Civil War, for instance, the Ku Klux Klan burned African American schools and churches and assaulted both blacks and their white allies in part to discourage voting.

According to a recent report by Orville Vernon Burton, a distinguished professor of southern history at Clemson, the state’s white leadership also adopted a policy of using what we would call today “mass incarceration” explicitly in order to suppress black voting further.

Those leaders first did so as part of the notorious Black Codes a year or two after the Civil War. Ten years later, they culminated those efforts by passing a state constitutional amendment in 1875 and a statute in 1877 that made convicted felons ineligible to vote in North Carolina.

Of course, the mass incarceration of black citizens outlived that historical moment and remains with us yet, though few remember its genesis in the post-Civil War period.

Challenging the Literacy Test

Back to John Wertheimer’s book: As James R. Walker, Jr., settled into his new home in Halifax County, local black activists began to educate him on the historic obstacles to voting there and in the other Black Belt counties. They focused especially on the literacy test.

As you’ll remember from the essay I mentioned earlier (“Summer of the Red Shirts”), when the self-avowed white supremacists came to power in North Carolina in 1898, they set about abolishing African American voting rights.

They did so by passing a state constitutional amendment in 1900 that included a number of different ways to prevent African Americans from voting. One was a literacy test. In the August 1900 election, they passed a constitutional amendment that required potential voters to demonstrate the ability to read and write a section of the state constitution.

The first discriminatory aspect of the literacy test involved who registrars required to take the test. In practice, they rarely required white people to take it.

In campaigning for the constitutional amendment of 1900, the white supremacists had promised their fellow white citizens that the literacy test would never disfranchise them, no matter how poorly they read or wrote.

On the other hand, they also promised that no black man, no matter how well educated, would ever be able to read and write well enough to pass it.

“The whites make no secret of the fact that the amendment to the Constitution to be voted on, if adopted, disfranchises only black men. They state this openly at all their meetings, and it proves a very effective argument in winning over the whites who cannot read or write.”

Richmond Times, July 20 1900

Even 60 years later, when an interviewer asked a registrar in Bertie County if he had ever seen a white person fail the literacy test, the registrar responded, “No. I mean I didn’t have any to try it.”

During those decades, North Carolina law also accepted the registrar’s assessment of literacy as final. A black person had no timely right of appeal. There was also no standard test or system of grading a test— even the makeup of the test was left up to the registrar’s discretion and could change from applicant to applicant, sometimes in minutes.

Registrars did not even have to justify their decisions in writing. They could simply say, “You failed.”

Registrars interpreted their constitutional duty in some rather extraordinary ways. In one case, for instance, a registrar in Enfield, in Halifax County, grew frustrated when a black applicant successfully transcribed a dictated passage from the state constitution.

The registrar then began to ask detailed civics questions about state government. The applicant answered them all correctly, except one: “Which has the most force, the militia or the General Assembly?”

It is a vague nonsensical question with no truly correct answer, but the registrar found the black applicant’s answer lacking and denied him the right to vote.

Other registrars asked black applicants similarly unreasonable questions. In Law and Society, Professor Wertheimer lists some examples: how many rooms are in the county courthouse? What are the names of all the signers of the Declaration of Independence? (There were 56 of them.) How many electoral votes does North Carolina have?

Another that struck me was this one: “And, if the NAACP attacked the U.S. government, what side would you be on?”

Single Shot Voting

James W. Walker, Jr. had his work cut out for him. In Law and Society, Wertheimer describes how Walker began his voting rights legal campaign not by challenging the literacy test, but by challenging a new state law against “single shot voting.”

As the civil rights movement gained momentum after the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. the Board of Education in 1954, a small number of black candidates began to run for office in North Carolina’s Black Belt counties for the first time since 1900.

In response, the North Carolina General Assembly passed a number of laws to make it more difficult for African Americans to gain elective office. One of them involved single shot voting.

In single shot voting, a voter only picks one candidate if there is an election for an office such as county commissioner or school board that has a group of candidates running for multiple at-large offices. By only voting for an African American candidate, black voters typically have a better chance to win in a field that otherwise includes white candidates because they aren’t voting for any of the African American candidate’s opponents.

In 1956 Walker sued the Halifax County Board of Elections on his own behalf for “throwing out his ballot on which he had voted [for] only one candidate in a race in which seven out of eight were to be elected.”

He had voted for Dr. Salter J. Cochran, a local physician and decorated war veteran who, if elected, would have been the first African American to serve in any public office in Halifax County since 1898, though the county’s population was 60% black.

Anxious that Walker might prevail, the N.C. General Assembly mooted his lawsuit by taking the right to vote for school board members away from all North Carolinians. Under a new law, state legislators, not local citizens, had the authority to select school board members in Halifax County and across the state.

That has happened a great deal in North Carolina’s history: in order to suppress the black vote in towns and counties with a large percentage of black voters, the General Assembly has repeatedly centralized power in Raleigh and weakened or ended the local election of political leaders—it was a historic trend that drastically weakened local democracy for people of all colors and backgrounds.

Grassroots Organizing

As James R. Walker, Jr. turned his attention to the literacy test, he began by building up a network of black activists spread out across the Black Belt and more than a dozen other eastern North Carolina counties.

Called the Eastern Council on Community Affairs (ECCA), the group drew heavily on the strength of existing local civil rights groups and acted as a communications network that monitored voter suppression and brought cases to Walker’s attention.

When ECCA activists made him aware of discriminatory or unfair use of literacy tests, Walker first responded by confronting registrars and protesting unfair denials of the right to vote.

In a sense, he and his colleagues were putting the registrars on notice: “you will no longer operate in the shadows. We’re not intimidated and we’re watching.”

That was an extraordinary step and one fraught with risk: white extremists targeted him and police at least in Enfield ordered Walker out of town and threatened him with charges after he defended several local African Americans that a local registrar had not allowed to vote.

Rising black demands for voting rights heightened the level of white intimidation of potential black voters, too. In Perrytown, in Bertie County, for instance, an eyewitness reported that a line of white men with German shepherds stood in front of the local registrar’s office.

According to the eyewitness, the white men held the dogs on leash when whites approached the registrar’s office but unleashed them and sicced them on black citizens when they sought to register.

Well into the 1970s, African Americans in those Black Belt counties faced cross burnings, vandalism, death threats, police harassment and other kinds of intimidation if they tried to register to vote. Voting rights were a life and death struggle and victories were hard earned.

Going to Court

In situations in which his advocacy for individual black citizens failed to get results, Walker moved into the courts. In 1956 he began by filing lawsuits against individual registrars for not administering literacy tests that were fair and legitimate.

For instance, in one case he sued a registrar named T. W. Cole for failing a highly respected minister, the Rev. Ernest Ivey, when he took the literacy test prior to the Democratic Party’s primary in May 1956.

A resident of Littleton, in Halifax County, the Rev. Ivey was 62 years old and quite literate.

In short order, Walker also began to challenge the constitutionality of the state’s literacy test. Prior to that Democratic primary in 1956, a number of African Americans in another Black Belt county, Northampton, contacted him after registrars refused to register them.

In one case, on May 12, 1956, a registrar named Helen Taylor failed an African American nurse and a college student for not answering questions about the state constitution to her satisfaction.

I don’t know anything about the nurse, but the college student was a young man named Alexander Faison of Seaboard, N.C. A veteran of the U.S. Air Force, he was a student at the North Carolina College for Negroes (now N. C. Central University).

Alexander Faison in his U.S. Air Force uniform ca. 1955. From “Remembering Attorney James R. Walker, Jr.,” a documentary posted on Youtube by James Vassor on Feb. 4, 2020. The documentary features interviews with two local activists that worked closely with Walker in Halifax County, N.C.

The incident with Faison and the nurse occurred at the W. H. Taylor general store, which served as the registrar’s office in the county’s Seaboard precinct. Faison, the college student, immediately sought out Walker’s legal help.

Walker went straight to the store in order to protest the registrar’s decision.

In a speech years later, Walker recalled that he had assumed that he just needed to bring Faison’s educational and military background to the registrar’s attention and she would likely relent and register him.

After all, if she would not register a college student who had honorably served his country in the U.S. Air Force, what African American would she register?

He soon discovered that Helen Taylor still refused to register Faison. But he also realized that day how many African Americans in Northampton County were hungry for voting rights.

“It just happened that as I got there there were about two dozen persons that had been denied in the last hour or so, all complaining about the same thing. Now [when] they heard that a lawyer was out there, they all came around wanting somebody to bring them some type of relief.”

They all told him, Walker remembered, “I am qualified and I want to register. Is there anything I can do about it?”

That afternoon Walker argued Faison’s case to Helen Taylor. According to Walker, she at first refused even to talk to him because he was an African American attorney, not a white attorney.

Walker persisted. But as he made his case, he crossed at least two of Jim Crow’s unwritten lines in the sand. He failed to defer to a white woman’s judgment and, as if that was not bad enough, he also allegedly shook his finger at her to emphasize his argument.

On seeing Walker point his finger at Ms. Taylor, her husband and the store’s proprietor called the police. Walker was arrested and charged with trespassing and disorderly conduct.

In those days state court judges nearly always supported the racial status quo in eastern North Carolina.

“When outsiders start to interfere with the affairs of Northampton County, we are not going stand for it,” the judge, Ballard S. Gay, said. He found Walker guilty and sentenced him to 90 days at hard labor and ordered him to pay a stiff fine.

By the time Walker had appealed his case to Superior Court, the state had changed the charges against him. Instead of charging him with trespassing and disorderly conduct, he was being tried for assaulting a female when he shook his finger at Taylor.

The jury found Walker guilty and the judge fined him $500 plus court costs and sent him to jail for a short time.

Arrests, fines, police intimidation, vandalism of his property—Walker experienced them all but he kept on coming. As he had always done, he continued to rely on local civil rights groups and local churches for financial support, plaintiffs and protection from white extremists.

An especially important ally was the Rev. Alexander Mosely, who was the leader of a civil rights group in Weldon that was affiliated with the Southern Conference Education Fund. The Rev. Mosely headed Walker’s defense fund in the case against him.

Lassiter v. the Northampton County Board of Education

As described in Wertheimer’s book, one of James R. Walker, Jr.’s most pivotal cases was Lassiter v. the Northampton County Board of Education. In that case, Walker and two African American attorneys in Raleigh, Samuel S. Mitchell and Herman Taylor, represented a farm woman named Louise Lassiter near the end of 1957.

Lassiter had tried to register to vote at the same general store in Northampton County where Walker had been arrested for trespassing and disorderly conduct.

Louise Lassiter, Northampton County, N.C. Photo courtesy, The Carolina Times (Durham, N.C.), March 30, 1957.

In Mrs. Lassiter’s case, she was far from illiterate, but Helen Taylor failed her on the literacy test when she allegedly mispronounced several words in the state constitution.

With Lassiter as plaintiff, Walker filed a federal lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of the state’s literacy test.

A week prior to the case being heard by a three-judge panel, the General Assembly again stepped in. Worried that federal courts might agree with Walker and overturn the state’s election law, the legislators revised the law and made the literacy test less arbitrary and discriminatory.

The revised legislation gave registrars less discretion to judge what constituted being able to read and write and allowed those that failed a literacy test a timelier right of appeal.

Walker and Lassiter wanted more: they wanted the literacy test ruled unconstitutional.

After failing at local appeals, Walker took Louise Lassiter’s case all the way to the United States Supreme Court. In the end, however, the Supreme Court ruled against her claims of unconstitutional treatment and supported the constitutionality of literacy tests as a qualification for voting.

In Lassiter, the U.S. Supreme Court thus affirmed the constitutionality of literacy tests across the U.S. On the other hand, the justices had also signaled that plaintiffs could still challenge literacy tests if they were administered in a discriminatory way—and hence violated the 14th Amendment.

Bazemore v. Bertie County Board of Elections

In Law and Society, Wertheimer chronicles what happened next. The next year, in May 1960, Walker appealed a registrar’s use of a literacy test in Bertie County for just that reason.

His client was a 47-year-old African American woman named Nancy Bazemore. She had failed a literacy test when she tried to register in the county’s Woodville precinct. As was common in Bertie County, the registrar dictated a portion of the state constitution to her and judged her literacy based in part on her spelling.

When the registrar found misspellings in Bazemore’s test, he failed her and ruled that she was not eligible to register to vote. Walker appealed the decision all the way up to the North Carolina Supreme Court.

Throughout the appeals, Walker argued that the state constitution referred only to an applicant’s ability to “read and write,” not take dictation or spell perfectly. He also argued that local registrars in Bertie County applied the literacy test in a discriminatory way because they did not require white applicants to take the test.

Walker prevailed in Bazemore v. Bertie County Board of Elections and it was a major voting rights victory: the justices not only ruled in Nancy Bazemore’s favor, but they also laid down a general set of guidelines to make the application of the literacy test fairer and less discriminatory throughout North Carolina.

The Bazemore ruling was an important success, but it did not challenge the constitutionality of literacy tests in general. The state supreme court justices took for granted that registrars would continue to administer the literacy test to some people and not to others—leaving lots of room for racial discrimination.

Nonetheless, James R. Walker, Jr.’s combination of legal advocacy and grassroots organizing played a key role in making the right to vote a reality in North Carolina’s Black Belt counties.

Wertheimer emphasizes that even Walker’s defeat at the U.S. Supreme Court in Lassiter v. the Northampton County Board of Education was an important achievement.

By making clear that not even the federal courts would address the literacy test or other electoral rules that discriminated against black voters, Lassiter helped voting rights activists across the South re-focus their efforts on the passage of federal legislation.

Their determination eventually led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and to federal court rulings that ultimately abolished literacy tests and many other discriminatory obstacles to voting.

The Struggle Continues

The struggle for voting rights in North Carolina’s Black Belt counties would continue long after James R. Walker, Jr.’s pioneering work. In the early 1960s, African American in the state’s Black Belt organized massive voter registration drives and widespread civil rights protests seeking the right to vote without intimidation.

Inevitably those voting rights activists faced cross burnings, drive-by shootings, police harassment and other kinds of intimidation.

There would also be at least two other important legal cases over voting rights in Halifax County alone that did not involve Walker—one in May of 1964, Alston v. Butts, and the other, Johnson v. Halifax County, in 1984.

Another local case, Johnson v. Branch, involved the firing of an African American teacher, Willa Johnson, for her support of voting rights efforts and other activism during the very intense civil rights movement that occurred in Enfield, in Halifax County, in 1963-64.

Willa Johnson (Cofield), Enfield, N.C., ca. 1964. Courtesy, National Education Association

The struggle for the most basic democratic right—one person, one vote—would continue and does continue today throughout the Black Belt and the rest of North Carolina.

But today, as our votes are being counted in this momentous election of 2020, maybe we would do well to remember that we walk in a well-trod path.

I thought about that the day before yesterday when I was at a Protect the Vote rally with my daughter and her friends.

In a way, I thought, we were standing with James R. Walker, Jr. and all the men and women who worked so hard to make the promise of democracy realer here in North Carolina— people such as Louise Lassiter, Nancy Bazemore, the Rev. Alexander Mosely, Willa Johnson and so many others whose names have been forgotten. It was a nice place to be.

Relief! Biden-Harris.

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Dr. Cecelski, I thought you might be interested to know that a student organization at UNC is currently raising funds to commission a portrait of James Walker, Jr.: https://www.diphi.org/cause/james-walker-portrait-fund/

As UNC reckons with commemoration on its campus, students lead the effort to ensure that remarkable people like Rev. Walker return to the narrative.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for letting me know & for the link- bravo to UNC’s students! Thats wonderful to hear!

LikeLike