A crew of the Waccamaw Lumber Co.’s railroad construction workers in North Carolina’s Green Swamp ca. 1910-15. The company relied on Italian immigrants to build its logging railroads, including an 18-mile line from its mill in Bolton into the Green Swamp. From the Waccamaw Lumber Co. Photograph Album & Journal, Rubenstein Library, Duke University

A few months ago, I discovered the case of James Torsigno, an Italian railroad construction worker who was unjustly charged with murder for killing a man in Belhaven, N.C, in the fall of 1920.

His story was fascinating in its own right. But in addition, while researching Torsigno’s fate, I also discovered that he was only one of thousands of Italian immigrant laborers who came south and built railroads in North Carolina in the early 20th century.

Their story has never been told. So over the last few weeks, I have set out to see what I could learn about both James Torsigno’s case and the history of those Italian immigrants at least on the North Carolina coast.

-1-

A little more than a century ago, just after the First World War, a young Italian immigrant named James Torsigno was one of approximately 600 workers building the New Holland, Higginsport, and Mount Vernon Railroad. Many– maybe even the large majority– were Italian and other immigrant laborers brought south from New York City.

The railroad that they were building was a 35-mile-long branch line that ran through some of the wildest, most remote swamp forests on the North Carolina coast. It ran from the Norfolk & Southern Railway’s main line in Wenona, in the southeast part of Beaufort County, to a massive pumping station at Lake Mattamuskeet, in Hyde County.

Map of the New Holland, Higginsport, and Mount Vernon Railroad. The station names– Kirwan, Wilbanks, Higginsport, etc.– were surnames of members of the company’s board of directors. From The Official Standard Time of the Railways and Steam Navigation Lines of the United States, Porto Rico, Canada, Mexico and Cuba (July 1928).

That pumping station could move 1,250,000 gallons of water a minute. The station’s coal-powered turbines were the beating heart of a grand, but ultimately futile plan to drain Lake Mattamuskeet, the state’s largest natural lake, located only a few miles from the Pamlico Sound.

That plan involved draining the lake, turning the lakebed into farmland, and building a town of new settlers (called New Holland), most of whom would come from the Midwestern states. The railroad’s main purpose was to deliver the coal necessary to keep the pumps working.

Pumping station at Lake Mattamuskeet (New Holland), ca. 1920-32. From B.W. Wells Lantern Slides, Special Collections Research Center, NCSU

During that fall of 1920, Torsigno worked along the railroad bed during the day, but he returned at night to his quarters at the NHH&MV’s grading camps. They were located on the railroad, deep in a swamp forest, 9 or 10 miles north of Belhaven.

According to news accounts, he had come from Italy so recently that he spoke barely a word of English.

The construction of the NHH&MV was a Herculean task. To run a railroad from Wenona to Lake Mattamuskeet, Torsigno and his co-workers had to cut a right-of-way through the swamp forest. They then had to dig deep ditches and use the earth to build a grading sufficiently high to raise the tracks above the swamp’s waters.

In some especially low spots in the swamp, they had to build, with cribbing hewn out of smaller trees, long, low trestles. They also had to build a railroad bridge across the Intracoastal Waterway.

Lake Mattamuskeet is located in Hyde County, N.C., on the northwest side of the Pamlico Sound. Map courtesy of Wikipedia

Torsigno and the other workers also had to cut and lay crossties, put down rails, build sidings, sink wells and construct water towers. And they did all that in the midst of a mosquito plagued swamp that must have seemed like a God forsaken land.

“A poor foreigner . . . among strangers”

James Torsigno’s troubles began on Wednesday, December 1, 1920. On that day, he apparently went to the grading camps’ chief foreman, a Mr. Hale, with some kind of grievance.

I do not know if his grievance concerned wages or the company’s failure to pay any wages at all (a frequent complaint on railroad construction crews at that time), or some other issue related to conditions on the job or in the camps.

Hale did not take Torsigno’s complaint well. According to later testimony from Victor Lewis, the police chief in Belhaven, the nearest town to the grading camps, the young Italian “was beaten up in a frightful manner.”

The next day, December 2, 1920, Torsigno, three other Italian workers, and “about a dozen Mexicans” left the railroad’s grading camp and came into Belhaven. Torsigno did not look good.

In Chief Lewis’s words, “One eye was closed and looked like a great red tomato; his nose was broken and caved in; one side of his mouth was swollen so that he could neither eat nor drink anything for two days; his arm was in a sling with a bad contusion at the wrist.”

With the help of an Italian co-worker who spoke English, Torsigno filed charges against Hale with a local magistrate.

Torsigno apparently stayed in Belhaven while he waited for Hale to be tried for assault before a district court judge. Two nights before Hale’s trial however, a large gang of Hale’s assistant foremen and at least one other local worker came into Belhaven looking for Torsigno.

According to Chief Lewis, that group of men “got Torsigno on the street and surrounded him while Wiley Radcliffe, a truck driver, began beating him over the head with a machine hammer.”

One of the younger gang members later told Lewis that Hale had told them to kill Torsigno “and run those other `wopps’ away from there.”

Though covered with blood, Torsigno pulled out a revolver and shot and killed Radcliffe. He escaped from the other men and went into hiding, but turned himself in two days later.

The case of James Torsigno was not the first incident that revealed tensions sometimes existed between local workers and immigrant laborers in Belhaven. In the winter of 1908, for instance, a melee involving local black and white workers and Greek immigrant laborers employed by Belhaven’s largest lumber mill led to town leaders calling in the Washington Light Infantry to restore order. Washington Progress, 19 March 1908.

Torsigno was sent to the state penitentiary in Raleigh, where he awaited trial for murder for more than seven months. He might well have been found guilty and executed if he had not met a Catholic priest who was visiting inmates at the penitentiary.

According to a later account, published in the Raleigh News & Observer more than 30 years after Radcliffe’s killing, the priest took an interest in Torsigno and brought an Italian-speaking parishioner with him to hear his story and see if they could do anything to help him.

After hearing Torsigno’s account, the Catholic priest contacted the Italian consul in Charleston, S.C. It was a wise move.

In the spring of 1906, a gunfight between Italian railroad construction workers and a posse in Marion, in the Appalachian foothills of North Carolina, had led to two deaths, seven other near fatalities, and hundreds of Italian laborers fleeing into the mountains. Since that time, Italian consulates in the U.S. had closely monitored reports of Italian immigrant laborers being abused.

In May 1906 a posse fired into a crowd of Italian railroad construction workers in a labor dispute in Marion, N.C., killing 2 and seriously wounding 7 others. They were among the 1,500 Italian immigrants building the South and Western Railroad from East Tennessee to Marion. An investigation by the Italian consul led to charges of peonage and other abusive treatment of the workers. “The foreigners stated that they were held practically as prisoners…and when one tried to escape he was caught and put to work in the tunnels during the day and locked up in the stockade at night.” The shooting started when the workers refused to allow the posse to confiscate their firearms. News & Observer (Raleigh, N.C., 8 June 1906)

After being alerted to Torsigno’s case, the Italian consul responded quickly. His office employed one of the most highly respected law firms in Washington, N.C., 25 miles west of Belhaven, to investigate Torsigno’s story and, if it bore out, to defend him.

The law firm did so, leading to the murder charge against Torsigno being dropped. He was however found guilty of carrying a concealed weapon and sentenced to a year in prison.

Victor Lewis apparently lost his job for supporting Torsigno’s version of the incident. In Elizabeth City, N.C., The Independent’s publisher and editor, the irrepressible W. O. Saunders, put it this way:

“Torsigno was a poor foreigner, jobless, friendless and among strangers. [Wiley] Radcliffe was a native of good family. The sympathies of the Belhaven Police Chief went out to the friendless Italian… and it cost him his job. (Independent, 19 Aug. 1921)

It could not have helped that Lewis had taken the side of an immigrant who was dark-skinned in a dispute with a white man. Most Italian immigrants in the U.S. had come from southern Italy or Sicily; they typically had darker skin than northern Europeans.

At that time, in fact, Italian immigrants in the southern states often faced discrimination based on the color of their skin. In many white people’s eyes, the southern Italians occupied a middle space in the American South’s racial order: not fully black, but also definitely not fully white.

Chief Lewis’s testimony is one of the rare times, in my experience, when we get a glimpse at what life was really like for Italian immigrants such as James Torsigno– and for other immigrants and black workers– in the railroad and logging camps of the North Carolina coast.

In a letter to the Independent (19 Aug. 1921), Lewis wrote, “Torsigno was beaten up the first time for sheer wantonness.” The second beating though was purposeful: the grading camps’ chief foreman, Hale, sought to eliminate the key witness in his trial.

But the most telling part of Lewis’s letter was just a single sentence at the very end. At that point in his letter, Lewis almost casually mentioned that he had hardly been surprised by either Torsigno’s beating or the attempt by the company’s foremen to kill him. He had, he said, often seen such viciousness at the NHH&MV’s grading camps.

“Three negroes have been killed in these same camps and scores of others brutally assaulted,” he testified.

The case of James Torsigno and Chief Lewis’s words—”three negroes… killed, scores of others brutally assaulted”— give us a searing glimpse at the lives of the people– the Italians, the African Americans, and others– who built North Carolina’s railroads, and how they were treated, and what they had to overcome.

-2-

The Italian Diaspora

Between 1880 and 1914, four million men, women, and children left Italy and came to the United States. They emigrated largely from Southern Italy, particularly the provinces of Calabria, Basilicata, Abruzzo, Campania, and Apulia, and also from the island of Sicily.

Most were part of Italy’s peasant class, people whose lot had rarely been easy. In the U.S., large numbers of the men first found jobs in mining camps, on railroad construction gangs, at canal digging sites, and in other heavy labor jobs that were grueling and often very dangerous.

A family of Italian immigrants on the ferry from Ellis Island, ca. 1905. Photo by Lewis Hine. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Not infrequently, they had their passage from Italy paid by U.S. middlemen who bought their ship’s fare and railroad tickets in exchange for a period of labor that bordered on indentured servitude. Many Italian workers sent a large part of their earnings back to their families in Italy.

Many also intended to return to Italy after they saved some money, and large numbers of them indeed did go back. Of the Italians that came to the U.S. between 1914 and 1920, almost half later returned to Italy. Those ritornati (“the returned”) were often called “birds of passage” in English.

Of the Italian immigrants that stayed in the U.S., by far the largest number made new homes in northern cities, such as New York, Philadelphia, and Providence. But many came south, too.

When a newspaper correspondent visited New Orleans in 1899, for instance, he found that, “They have been arriving for the last 20 years at the rate of many thousands each year” and had been “enduring persecution and overcoming prejudice by mere persistence.”

The correspondent also noted, “They are willing to live in the same cabins as the negroes and to work with them in the fields on equal terms, and they work hard and faithfully.” (Pacific Commercial Advertiser, 22 Aug. 1899)

“Go south, Pietro, Paolio and Giovanni!”

The first mention that I found of immigrant laborers from the Italian Diaspora in North Carolina was a brief and none too kind article that first appeared in the Goldsboro Argus and was later reprinted in The Weekly Star in Wilmington, N.C., on November 14, 1890.

In the Argus‘s story, the reporter wrote, “There are a great many Italian laborers, uncouth and savage looking, … pass[ing] through this city daily, in carload lots, en route for South Carolina and Florida, to work on the railroads and phosphate beds of those states.”

The Argus’s description of the Italians passing through Goldsboro—”uncouth and savage looking”— is telling. That was the kind of language that white southerners often used to describe African Americans, and the work that the Italians were being sent to do had theretofore been the kind that was reserved for African American laborers.

Goldsboro in 1890 was a railroad town, where three major railroads met and passengers often changed trains. Downtown (seen here ca. 1870) was filled with locomotive smoke, the sound of railroad whistles, and passengers from near and far. Courtesy, CP&L Photo Collection, State Archives of North Carolina

Within a few years, Italian immigrant workers were not just passing through the state’s railroad depots. They were arriving in North Carolina itself, especially on the state’s coastal plain and in the mountains. They came in greatest numbers to railroad construction camps, but also to mining and logging camps, mill towns, and other work sites.

All or nearly all of those Italian workers arrived via the padrone system, in which an Italian labor boss most typically recruited the immigrants in New York City, fresh off Ellis Island, and transported them south to a prearranged work site in North Carolina.

In the padrone system, the Italian labor boss negotiated the terms of the workers’ contracts, arranged travel and housing, and often operated a commissary where the workers could purchase staples for Italian cooking and a few other supplies.

In all matters, the padrone was the middleman between a company’s managers and the Italian laborers, and of course he took a portion of the workers’ wages for his services.

One of the first places that Italian immigrants found work in eastern North Carolina was the town of Kinston, the county seat of Lenoir County. They were not recruited there to build a railroad though. In the summer of 1904, a local building contractor, the West Construction Co,. arranged to have several crews of Italian immigrants from the New York City area come to Kinston to build the city’s waterworks and sewage system.

In an interview with the Raleigh Farmer and Mechanic (7 Feb. 1905), the West Construction Co.’s superintendent, a Mr. Rogers, explained his enthusiasm for employing the Italians in this way: “They want to work; they want the money; will work overtime—every day and Sundays, too, or whenever called on—steady as a clock.”

The arrival of the Italian workers in Kinston prompted the editor of the local newspaper, The Daily Free Press, to reprint an article from the New York Sun that was wildly enthusiastic about the prospect of Italian immigrants replacing the African American field workers who had been fleeing the rural South since the Civil War.

The Sun’s story read: “Go south, Italians, go south. There is money in the cotton patch. There is more comfort in a little home under the trees than there is a tenement home. There is both room and need for a million or two sober and industrious cotton raisers and an abundant reward for every one of them. Go south, Pietro, Paolio and Giovanni!”

At the end of the Sun’s story, the Free Press’s editor had added, “Thus says the New York Sun. And it gives to the swarming thousands of the metropolis some of the most wholesome advice that they can get.”

The Italian immigrants that worked for the Cape Fear Fisheries’ Co. may have worked on the company’s boats (such as the Joseph Wharton, pictured here under construction in 1904), but more likely worked in the company’s fertilizer factory on the Cape Fear River. Courtesy, Hagley Museum and Library

I also found several references to Italian immigrant laborers working in maritime trades on the North Carolina coast. For instance, in the same year as the Italians arrived in Kinston, the Cape Fear Fisheries Co. brought 22 Italian immigrants south to work either on its boats or at its fertilizer factory at Brunswick Town on the Cape Fear River. (Wilmington Morning Star, 22 Nov. 1904).

Similarly, on another part of the coast, Italian laborers were part of the D. W. Taylor Co.’s work crews that hauled rock to Cape Lookout to build the breakwater that is still there today.

The Railroad Builders

While Italian immigrants did a variety of other jobs in North Carolina, the driving force behind their recruitment was the construction of railroads. Some of those railroads were being built to serve as general carriers of freight and passengers, but far more—especially on the coast and in the mountains—were being built by lumber companies.

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, a tremendous lumber boom was occurring across the North Carolina coast. Lumber companies were cutting down thousands of square miles of forestland, including ancient, old-growth groves of a size and grandeur that few of us could imagine today.

Scores of lumber mill boom towns sprang up. Logging camps seemed to be everywhere.

Railroad construction was central to that lumber industry boom. Lumber companies built hundreds if not thousands of miles of main lines, branches, and spurs to carry logging equipment into remote forests, to haul logs to their mills, and to transport lumber to seaports and overland to the northern states.

The steamer Ocracoke at Ocracoke Island, N.C., 1899. From Phillip Howard’s glorious blog, Ocracoke Island Journal

In the summer of 1904, for instance, the Daily Journal in New Bern, N.C. (17 Aug. 1904), reported that 30 Italian railroad workers had just arrived aboard the steamer Ocracoke. They were immediately sent to a construction camp of the Pamlico, Oriental & Western Railroad that was located two miles north of New Bern.

Those Italian laborers had come directly from the construction of another railway, the Pennsylvania Railroad, a sprawling network of rail lines that had originally run from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh but by 1904 ran through eight or nine states.

Twenty more Italian workers arrived in New Bern a week later (New Berne Weekly Journal, 17 Aug. 1904). By August 26, a total of 160 men, most of them Italian immigrants, were working on the railroad. Another New Bern newspaper, the Daily Journal, reported that “A large part of the laborers are the Italians that have been brought here in large numbers from the north.” (Daily Journal, 26 Aug. 1904)

P. O .& W officials said that they expected a total of 250 men to be at the construction camp by the 1st of September.

From the beginning, the work on the P. O. & W. took a heavy toll on its Italian builders. According to W. A. Cullen, the president of one of the railroad’s contractors, he paid his 80 Italian employees 13 and ½ cents an hour and worked them 10 hours a day, seven days a week.

He also went out of his way to say that he paid the Italians 10 cents a day more than the company’s African American workers, and–if he followed the typical practice– he paid his white workers at least somewhat more than the Italian workers.

The August heat was especially hard to bear. The workers were clearing right of ways through swamp forests, digging ditches, constructing grades, cutting crossties, and building trestle bridges through the hottest, most humid part of the summer.

The Pamlico, Oriental & Western Railroad ran from New Bern to Bayboro, the seat of Pamlico County, N.C. Map courtesy, Wikipedia.

After only a week on the job, five Italian laborers succumbed to heat exhaustion while working in a pocosin swamp on that north side of the Neuse River. (Daily Journal, 24 Aug. 1904)

Ten days later, the headline of the Daily Journal read: “Dago Uprising.” (Forgive my use of that pejorative; it seemed necessary to show attitudes toward the Italian immigrants at that time.)

According to a highly uninformative report, one of the P. O. & W. Railroad’s Italian laborers had questioned a foreman about his paycheck, leading to a scene, similar to the one that James Torsigno later experienced, in which he was assaulted for his alleged temerity.

The account of the incident in the Daily Record read: “For an answer he received a slap by which he fell to the ground. The sight of this set the blood of the belligerent foreigners boiling and they used clubs, sticks, stones, and even flourished their long-bladed steel knives which they carry for just such emergencies.”

A little parsing of the word “belligerent”

The Daily Record’‘s use of the word “belligerent” to describe Italian immigrants that did not docilely accept one of their own being knocked to the ground was telling.

Self-described “white supremacists” had come to power across the state of North Carolina in 1900. In their political lexicon, a “belligerent,” “hostile,” or “disreputable” black person was one that dared to act as if he or she was the equal of a white man or woman. In their eyes, such an individual was a danger to society.

The fact that the Daily Record used the word in the same manner to describe Italian immigrant laborers says a good deal about how white leaders saw them fitting into the state’s Jim Crow society.

The Daily Record’s story continued, “It was a riotous crowd for a few minutes, but they were quieted down and nobody was injured in the fracas.” That statement no doubt left the newspaper’s readers suspecting that there was more to the story, and probably imagining the worst.

The incident again highlighted the in-between status of the Italian immigrants from southern Italy and Sicily.

On one hand, the P. O. & W. ’s contractors paid the Italians a few cents a day more than black workers.

But on the other hand, the railroad’s foremen obviously expected a kind of subservience and deference from the Italian immigrants that was very similar to what southern whites had demanded of black workers since the earliest days of American slavery.

In that system, questioning a white man’s accounting, protesting working conditions or– and my mother used to tell me about this when she was growing up on the North Carolina coast– even speaking directly to a white foreman was crossing a dangerous line– and far too often had brutal repercussions.

Rails and Sawmills

An unknown but large number of the region’s other railroad companies also relied on Italian immigrant laborers. As early as 1905, for instance, Italian crews made up a large part of the workforce either building or doing maintenance work on the Atlantic & North Carolina Railroad, which ran from Morehead City to Goldsboro.

According to Raleigh’s Farmer and Mechanic, (7 Feb. 1905), a smaller number of “Finns, Poles, Portuguese, and Hungarians” also worked on the A&NC’s construction crews.

On June 8, 1906, the Wilmington Morning Star reported that “there are already in North Carolina several thousand Italian laborers, most of them engaged in railroad building in the western and eastern parts of the state.”

The newspaper observed that 200 more Italians had just arrived at the train station in Wilson, N.C. They were bound for the construction camps of the Raleigh and Pamlico Sound Railroad, which was running a new line from Wilson to Raleigh and also a line from Washington, N.C., to Bridgeton, just across the Neuse River from New Bern.

The R. & P. S. Railroad’s managers were expecting 300 more Italian laborers in the following days.

Around that same time, crews of Italian immigrants began working for several of the lumber companies in and around New Bern, including the Pine Lumber Company (pictured below).

Many of those laborers built logging railroads, but many also seem to have worked in the town’s sawmills (of which there were more than 20 at that time).

In New Bern’s Lumber Mills

The special enthusiasm of New Bern’s lumber mills for employing Italians and other immigrant laborers may have been rooted in the white supremacy movement of 1898, the one that is most remembered for the Wilmington Massacre.

That white supremacy movement reached into every corner of North Carolina, not just Wilmington.

In New Bern, the leaders of the white supremacists included the town’s leading bankers, lawyers, and industrialists. In the summer of 1898, they made a pledge to the town’s white working class that, if white working men supported their movement, they would fire all their black workers from non-menial jobs and replace them with white workers.

Late in 1899, James A. Bryan composed a list of the black workers that he fired at the Atlantic & North Carolina Railroad Co.’s machine shops and a list of all-white individuals he had employed to replace them. He also noted that he fired 5 white individuals who had been politically aligned with black voters in the 1898 elections. Document in the Financial Papers, (Series 3.1), folder 555 (1899), Bryan Family Papers, Southern Historical Collection, UNC-CH.

That group of business leaders was led by James A. Bryan, the president of New Bern’s largest bank, president of the Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad, and treasurer of the aforementioned Pamlico, Oriental & Western Railroad.

With the white supremacy movement’s success, Bryan and the town’s other white employers lived up to their pledge– leading me to wonder if the purge of black workers led to a labor shortage in New Bern’s lumber mills that prompted industry leaders to seek out Italian immigrant laborers as replacement workers.

Things did seem to be getting lively in neighborhoods around New Bern’s lumber mills. In those parts of town, the aromas of new kinds of cooking, the cadence of foreign languages, and the music of many nations filled the streets, though not everyone seemed happy about it.

At the end of 1904, for instance, a local newspaper complained that “the Negroes, Portuguese and Italians” in the vicinity of the Pine Lumber Co.’s mill “are decidedly disagreeable in their habits and of a desperate character.” (New Berne Weekly Journal, 20 Dec. 1904)

The Pine Lumber Co.’s mill in New Bern, N.C., ca. 1924. From Albert Y. Drummond, Drummond’s Pictorial Atlas of North Carolina (1924)

Elsewhere on the North Carolina coast, Italian immigrants were also recruited, probably to do railroad construction work, though possibly for logging or mill work, by the Butler Lumber Company, a mammoth complex in Boardman, in Columbus County.

Other Italians built railroads into the Green Swamp for the Waccamaw Lumber Co.; laid trolley lines for the Tidewater Power Co. in Wilmington; and played a big part in building the Norfolk and Southern Railroad’s 5-mile-long trestle across the Albemarle Sound, reportedly the longest bridge of its kind in the world at that time.

Postcard of a train crossing the Norfolk & Southern Railroad’s trestle across the Albemarle Sound, ca. 1918. Courtesy, Wikipedia

At least 25 Italian laborers also worked for the Goldsboro Lumber Co. in Dover, in western Craven County. Evidently some of them were employed at the company’s sawmill, while others toiled on the company’s logging railroads. (Daily Free Press, Kinston, N.C., 15 Nov. 1904)

A Goldsboro Lumber Co. crew loading logs, early 1900s. Re-registered as the Goldsboro Lumber & Railroad Co. in 1908, the company owned 36 miles of track between Dover and Richlands, N.C. From National Archives RG 95-GP, Forest Service Records, General Subject Files (Neg. #23336). (Special thanks to Patrick Milan & George Lane.)

Other Italians worked for the Rowland Lumber Co., which had a mammoth mill in Bowden, a village in southern Duplin County. The company employed so many Italian immigrants that a neighborhood in Bowden was called “Little Italy” for many years.

Those Italian laborers most likely worked on the company’s main line, the Kinston and Carolina Railroad, as well as its many spurs, but may also have worked in its sawmill.

The Kinston and Carolina RR ran from Kinston to Pink Hill, and then I think later to Beulaville.

-3-

“An Italian city . . . at Honey Island Swamp”

Newspaper accounts and one very special manuscript collection– the Waccamaw Lumber Company Photographic Album and Journal at Duke University’s Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library— give us special insight into the lives of the Italian immigrant laborers that built railroads for the Waccamaw Lumber Company.

Led by a Detroit industrialist, a group of lumbermen and financiers largely from the Great Lakes States established the Waccamaw Lumber Co. in 1904. Over the next several years, they acquired massive tracts of forestland, totaling in the neighborhood of 230,000 acres, in Columbus and Brunswick County, N.C.

The company’s holdings included all or nearly all of one of the most ecologically precious wetlands in North America, those of the Green Swamp.

After securing deeds to the land, the company began construction of a sawmill in Bolton, northeast of Lake Waccamaw, in 1907. According to the Wilmington Messenger (20 Aug. 1907), the first 80 Italian immigrant laborers arrived there that August.

Bolton is 30 miles west of Wilmington, in Columbus County, N.C. Brunswick County is just east of Columbus County. Map courtesy of Wikipedia

An Italian padrone, Antonio Ross, had recruited the Italian laborers in Trenton, New Jersey, and Philadelphia. On their arrival in Bolton, they built a camp outside the small town.

The Waccamaw Lumber Co.’s mill in Bolton ca. 1910-20. The round tower is the furnace, which burned bark and other scrap wood to power the mill’s saws. From the Waccmaw Lumber Co. Photograph Album and Journal, Rubenstein Library, Duke University

Three months later, the Wilmington Morning Star (23 Nov. 1907) reported that the group had grown to “a force of something like 100 Italians.” They had begun building an 18-mile-long railroad from Bolton to the company’s logging camp in Honey Hill Swamp.

Built on the side of Juniper Creek, just north of what is now the site of the Nature Conservancy’s Green Swamp Preserve, that logging camp was called Makatoka, named, it is believed, for an Indian tribe that had once occupied the area.

Makatoka had its own post office, company store, and apparently an abundance of liquor houses and gambling dens. Judging by its reputation, one rarely had to look hard for a drink or a knife fight.

Workers posing at the commissary at the Makatoka logging camp, ca. 1913. The men in white on the left are probably the camp’s cooks. From Waccamaw Lumber Co. Photograph Album and Journal, Rubenstein Library, Duke University

In 1983, the students at Hallsboro High School, 10 miles west of Bolton, featured several interviews with surviving employees of the Waccamaw Lumber Co. in a local heritage journal that they called Kin’ Lin’.

One of those former employees, a Mr. Banker, remembered Makakota in this way:

“Back in those days, Makatoka was known as rough spot. They would sometimes put on a shindig, drink about all night and shoot people. Play music and whoop it up. I know because at one time I was in town there.”

Mr. Baker might—or might not— have been exaggerating a bit when he said, “They didn’t care! They’d just as soon shoot you as not. They’d kill a man and set right on him and gamble all night long.”

Even if his memories might have been colored a bit by the passage of time, Mr. Baker’s words do seem to capture the spirit of Makatoka early in the 20th century.

All kind of men lived in Makatoka: local blacks, whites, and almost certainly members of the Waccamaw-Siouan Tribe or other Indian people; Gullah-Geechee loggers recruited in the Low Country of South Carolina; and, in addition to the Italians, immigrants from at least Poland, Russia, Sweden, and Hungary.

The Italian immigrants occupied a group of shanties set off by itself, a short way from the rest of Makatoka.

Another of the students’ interviewees, Arthur Little, began working at the Waccamaw Lumber Co. in 1917. But in his visit with the Hallsboro students, he remembered Makatoka even earlier, when he used to take eggs and produce to sell there as a small child.

One of the Waccamaw Lumber Co.’s logging trains headed to its mill in Bolton, ca. 1910-20. From the Waccamaw Lumber Co. Photograph Album and Journal, Rubenstein Library, Duke University

“Makatoka went on record as being the meanest lumber camp in North Carolina,” he said. “But all told, they were rough and if one got mad at you, he would kill you.”

On the other hand, Little recalled, “If one of them told you something, his word was his own. He could be just as mean as he could be, but if he told you something, you could count on it.”

Barnes Little, another of the Waccamaw Lumber Co.’s veterans, remembered that “they had an Italian city down there at Honey Island Swamp.”

He continued: “They even had their own brick kilns where they baked their bread. Me and my daddy has been down there and bought light bread from them. They had their own bakery, and they had a shelf they’d put the loaf of bread on and push it in [and] a paddle with a long handle on it.”

Barnes Little believed that more than 10 families lived there when he first visited the Italian camp.

“Those that didn’t get killed eventually left here,” he remembered, with the exception of two men, Frank Severino and Charlie Soares, who married local women and settled down in Columbus County.

“Those that didn’t get killed”

The perils that the Italian immigrants faced on the lumber railroads is one of the strongest themes in that special issue of Kin’ Lin.’ In their interviews, the company’s former workers seemed to be reeling off a steady narrative of fatalities and lesser accidents that make Barnes Little’s comment—those that didn’t get killed—seem deeply ominous.

A piece of the Italian laborers’ handiwork: the Honey Island Trestle, built nearly a mile long through Honey Island Swamp ca. 1910-1915. From Waccamaw Lumber Co. Photograph Album and Journal, Rubenstein Library, Duke University

The accounts of accidents and fatalities on the company’s railroads that are mentioned in that issue of Kin’ Lin’ date back mainly to the late 1910s and 1920s. However, in the region’s newspapers, I also found other, earlier accounts of tragic accidents involving the company’s Italian railroad builders.

The one that caught my attention most forcefully was a logging train derailment that led to the death of three Italians and a Russian on the morning of June 28, 1911.

That incident occurred on a stretch of the Waccamaw Lumber Co.’s track 18 miles south of Bolton, somewhere near Makatoka. Something had made the logging train jump the tracks. As the train careened along the line’s crossties, six men were thrown off.

Two had survived. Four did not. The three Italian fatalities were Joseph Ross, Gaetano Naredo, and Dominico Serinci.

Joseph Ross was the son of Antonio Ross, the Italian camp’s padrone. He did not even work for the Waccamaw Lumber Co.; he lived in Trenton, New Jersey, and was only visiting his father when he was killed.

According to the Wilmington Morning Star (2 Nov. 1911), the Russian logger’s name was Forester Rhuhady.

Company officials did not believe the train derailment was an accident. According to news reports, they had been in a longstanding battle with settlers who had lived in the Green Swamp before the company’s arrival. Those settlers lived off the land, eking out livelihoods no doubt with a good bit of guile and craft.

Those local settlers– some of them, anyway– evidently did not acknowledge the company’s ownership of the lands on which they had been living. They had stayed on the land.

They had not stayed on the land quietly, however. Newspaper reports of “squatters” harassing the Waccamaw Lumber Co.’s logging operations go back at least as far as another logging train derailment in November 1909.

That incident occurred on track two miles south of Makatoka, in the heart of the Green Swamp. A logging train came off the track, killing a Russian logger and injuring eight or nine other men. Sabotage was widely suspected.

The Wilmington Morning Star was probably exaggerating when it published a headline, in reference to the situation in the Green Swamp, that read “A Reign of Terror is Existing.”

Wilmington Morning Star (Wilmington, N.C.), 16 Nov. 1909

On the other hand, according to company officials, unknown persons had been firing gunshots into Makatoka (evidently aiming at foremen) and “spiking timber,” a potentially very dangerous and destructive act that these days is usually associated with “eco-terrorism.”

If I am grasping this situation in anywhere close to its fullness, this battle between a logging company and local settlers in the Green Swamp was emblematic of the kinds of conflicts– battles over land rights, strike breaking, and others– that U.S. companies often placed Italian and other immigrant laborers.

In such cases, the immigrant laborers often found themselves in situations that were fraught with peril, prone to eliciting local resentment, and not of their own making.

A funeral Mass for the three Italians who died in the 1911 incident– Joseph Ross, Dominico Serinci, and Gaetano Naredo– was held at St. Thomas Catholic Church in Wilmington. They were then laid to rest at the Catholic cemetery on Wilmington’s Middle Street.

Joseph Ross’s family later had his remains taken back to Trenton, N.J., where he grew up and where his grandmother and grandfather still lived. I do not know what happened to Forester Rhuhardy, the Russian logger. I do not know if he ever had a funeral or if he had loved ones who said prayers for him and mourned his loss.

“They laid down their tools and walked out”

In the February 7, 1905 edition of Raleigh’s Farmer and Mechanic, W. A. Cullen observed that Italian immigrant laborers were somehow uniquely suited to building railroads. He was quoted as saying, “No better labor than Italian can be procured for railroad work; They are peaceable [and] have given us absolutely no trouble.”

Cullen was president of one of the Pamlico, Oriental, and Western Railway’s contractors, but his statement– at least about the Italian workers’ docility– seems incongruous with the historical record. Everywhere I looked, I seemed to find abundant evidence of strikes, walk-outs and other labor disputes involving Italian immigrant laborers and their employers in the early 20th century.

The Italian laborers that came south to build Kinston’s waterworks and sewage system went on strike in September 1904. “They laid down their tools and ‘walked out,’” the Kinston Daily Free Press reported on September 14th of that year.

The next day, the newspaper’s editor simply sighed, “Thus far our experiment with Italian adventurers has been a failure.”

He fretted that the Italians had brought “strikes and boycotts that are as yet foreign in spirit to our southern labor system.” More Italian laborers arrived in Kinston two months later, but few stayed on the job long, leaving before they had even paid the company back for their ticket south.

“The woods around Kinston must be full of them by this time,” the newspaper noted on November 12.

Two years later, Italian immigrant laborers walked off their jobs on a construction site of the Raleigh and Pamlico Sound Railroad, apparently on the segment of the line that was being built between Bridgeton and Washington, N.C.

On March 19, 1907, the New Berne Weekly Journal reported that approximately 30 of the railroad’s Italian workers had left their camp and come into New Bern after being paid on a Saturday night. Evidently, they had had enough of North Carolina. They intended to get passage on the next steamer to New York City.

A few months later, news reports give us an inkling of the working conditions that led them to abandon their jobs . That summer, according to the Journal (16 July 1907), U. S. Department of Justice (DOJ) agents charged one of the railroad’s contractors, E. A. Kline, with peonage, or debt slavery.

According to the DOJ agents, the railroad’s workers—including Italians, but also Austrians, Poles, and Russians— “have been compelled to submit to much cruelty. These men are unable to speak a word of English. They are said to be kept like pigs in the pen.”

In the fall of 1904, another group of Italian railroad builders fled a camp on the Goldsboro Lumber Co.’s logging road near Dover, 25 miles west of New Bern. They apparently escaped on two of the railroad’s hand cars. (Daily Free Press, 15 Nov. 1904.)

“Their grievance is a righteous one”

In the winter of 1912, a labor dispute also roiled the Waccamaw Lumber Co.’s logging operations. According to the Wilmington Dispatch (29 Jan. 1912), 25 or 30 “foreign laborers”—all or nearly all Italian—had walked off their job and made a trip into Wilmington to seek redress.

They told officials in Wilmington that they had been in Bolton and the Green Swamp for four months, but they had yet to be paid any wages. “The men state that they came here to seek legal advice,” the newspaper’s correspondent observed.

In addition, “They declare[d] that they were fed only the plainest food, and hardly a proper amount of that, and assert that their stay has been unsatisfactory in many other ways.”

The Italian immigrants had left Bolton, the site of the Waccamaw Lumber Co.’s sawmill, after one of them had been, in the newspaper reporter’s words, “seized and beaten unmercifully.” He had apparently demanded better rations from one of the company’s foremen.

According to the workers’ account, two other Italian laborers had come to the first man’s rescue. A fight ensued. “Knives, it is said, were freely used in the conflict,” the Dispatch reported. The company’s foremen eventually subdued the three men, then locked them in a boxcar overnight.

“They were taken out by the other Italians this morning. In a body they came to this city to seek legal redress…,” the Italian workers, some of whom could speak English, told the Dispatch’s correspondent.

The writer observed further, “The foreigners are emphatic in their statements that their grievance is a righteous one.”

-5-

A Change in Immigration Policy

Italian immigrant laborers only came to North Carolina in sizable numbers for a quarter century. The First World War curtailed Italian immigration for a time, but more significant was a landmark change in U.S. immigration policy the following decade.

In the early 1920s, the U.S. Congress passed two major bills—the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Act of 1924— that drew strong support from many different parts of the country’s political spectrum, including eugenics advocates and others with ideas of fostering a more “racially pure” American society.

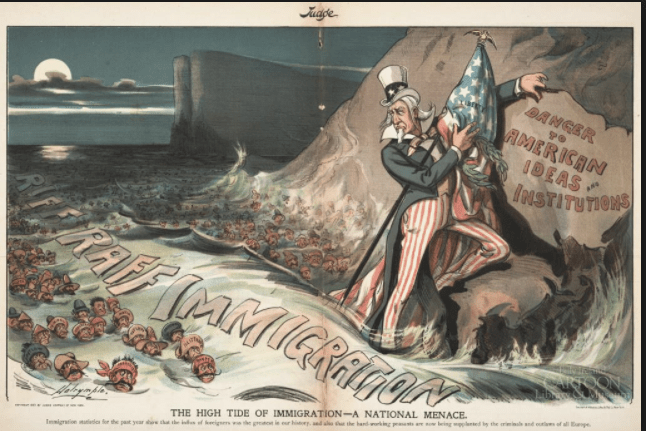

This cartoon reflects the widespread fear of immigration from southern and central Europe that many white Americans felt in the late 19th and early 20th century. Louis Dalrymple, “The High Tide of Immigration—A National Menace,” Judge Magazine, August 22, 1903. Courtesy, The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

Both pieces of legislation placed tight restrictions on immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe. In addition, the Immigration Act of 1924 banned immigrants from Japan, China, and other parts of Asia from coming to the U.S.

After completing the jobs that brought them south, some Italian immigrant laborers stayed and made new lives on the North Carolina coast. Those that did stay—such as Frank Severino and Charlie Soares at the Italian camp in Honey Hill Swamp—had often married local women.

Most of the Italian immigrants did not stay, however. They came south to do a job and make enough money to get a foothold in America, then returned to their families in New York City or elsewhere in the urban north. A smaller number no doubt went back to Italy.

I was not able to find out what happened to James Torsigno after he finished his sentence at the state penitentiary in Raleigh. But I do know that, in time, Italian immigrant laborers like him were a rarer and rarer sight building railroads and working in logging camps, and then they were gone, and soon forgotten, altogether.

Pingback: The Road to Makatoka: Logging the Green Swamp, 1910-1930 | David Cecelski

Pingback: The Last Days of the East Dismal Swamp - Rabit News

Hi David,

I was recently doing some Google searches on Italian railroad workers and came across your article on James Torsigno. My expertise is Italian genealogy.

I found the 1920 census record on the men you describe in your article. The spelling in the census is a little different from what appeared in the newspaper articles. The census shows him as Jim Tersegni. In looking at the list of Italian workers, it appears that the census taker was not familiar with Italian names and many of the names were mangled.

“United States Census, 1920”, , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MZVL-8J8 : Sun Mar 10 18:25:56 UTC 2024), Entry for Jim Tersegni, 1920.

I noted that there were several men in the group of workers listed in the census that were born in Pennsylvania.

I will also mention that men named Vincenzo often become James in the U.S.

I found several men with similar names to James Torsigno in New York, Ohio and Pennsylvania in the records of the 1930s and 1940s. It is hard to connect them definitively with Torsigno or Tersegni of North Carolina in 1920.

However, after closer inspection of the 1920 census on FamilySearch, I noticed that someone had attached the census record to James Vincenzo Tersegno 1894 – 16 December 1933 •L45C-K4H.

https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/details/L45C-K4H

There is a detailed timeline of this man here:

https://www.familysearch.org/tree/person/timeline/L45C-K4H

There are several contributors to the profile of James Vincenzo Tersegno who might be descendants. I added a link to your article as a note for the family.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Superb job

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much!

LikeLike

Please email this article to johnmitchener@live.com Thank You! 10/30/2024

LikeLike

I live in Marion, NC. I’m Italian, originally from New York. I see a lot Italian influence in the old homes in Marion. Do you have any other stories about Italians in North Carolina?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to hear from you. I’m afraid I don’t. I focus on the history of Eastern N.C. and the story about the Italian railroad builders was a real revelation to me– I think we’re just starting to discover the Italian immigrants and other immigrants as well that played an important part in the region’s history. I did however just recently do a story that featured some Italian immigrants in the state’s oyster industry– you can find that story here. https://davidcecelski.com/2024/08/23/a-forgotten-people-bohemian-oyster-shuckers-on-the-north-carolina-coast-1890-1914/ Thanks for writing!

LikeLike

Thank you for this. I found your post looking for information on the Waccamaw Lumber Company. My grandmother’s family is from Makatoka and I recently found some newspaper articles about them being arrested and tried for several incidents related to the logging camp there. Nice to have more context about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person