Exploring Eastern North Carolina’s History at the Center for Brooklyn History’s Othmer Library

At the Othmer Library in Brooklyn, N.Y., the other day, I found a story that I thought spoke in a moving way to the history of Eastern North Carolina and the Great Migration— and especially to the historic ties between the region’s African American communities and New York City.

The Great Migration was of course the movement of some six million African Americans out of the rural and small-town South to cities in the North, Midwest, and West between 1910 and 1970.

The story I found was told by an African American woman named Evangeline “Eve” Porter. She was born in Rocky Mount, N.C., in 1932– and the story is about her when she was only nine years old.

In an oral history interview preserved at the Othmer Library, Ms. Porter recalled her decision to leave Rocky Mount, her first impressions of New York City, and the life that she made in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights neighborhood.

Evangeline “Eve” Porter was interviewed as part of the Crown Heights Oral History Project in 2010. Photo courtesy, Crown Heights Oral History Project

In this excerpt from that interview, Ms. Porter describes her first trip to New York City in 1941 or ’42.

She must have really been something. At the time, she was full of dreams and determination, but she was still a child, she had never been away from home before, and she made the trip all by herself.

Ms. Porter was interviewed in 2010 by students from Brooklyn’s Paul Robeson High School, as part of the Crown Heights Oral History Project. She was 78 years old at the time. These are her words, very lightly edited by me.

Evangeline “Eve” Porter

Well, in my earliest memory of Brooklyn, because I came from North Carolina, I was nine years old. I came to New York at nine, going on 10, alone. Because I told my– I lived with my grandparents, and I told my grandmother that I was grown.

And the fact I felt– the reason I felt I was grown is because my grandmother– who couldn’t read or write, not good– I paid her bills and I banked her money, the little that she had; that she made in a tobacco factory. And I took care of all of her shopping, you know, buying her stockings and hats for church on Sunday. And I just felt that I was grown.

So I asked her if I could come to New York to see my Aunt Edna and my Aunt Mary and my Uncle Jerry, and she said, “Sure.”

After settling in Crown Heights, Ms. Porter was often involved in struggles to defend the rights of the neighborhood’s people, and to uplift the neighborhood. Among other things, she was the founder and president of the Crow Hill Community Association, which was one of the sponsors of the Crown Heights Oral History Project. This photo shows the Association’s Franklin Street Halloween Parade back in 2012. Photo courtesy, Crow Hill Community Association

And with that, my grandmother didn’t tell me anything that couldn’t be done. I said, “OK.”

So I said, “You’re going with me?”

She said, “No.”

“Well, who’s going with me?”

She said, “You’re grown. You go by yourself.” And I did. I was determined to do it. I was a big girl. And I came by myself with a notice around my neck telling where I was going and my name.

My granddaddy did that. He wrote, “My name is Evangeline Porter. I am going to 1338 Bergen Street, Brooklyn, New York. I am going on the 7:15 train.”

And that was it….

The interviewers for the Crown Heights Oral History Project were a remarkable group of students from Paul Robeson High School in Brooklyn. Over the 2009-10 school year, they interviewed 43 longtime residents of Crown Heights, including Evangeline Porter. In this photo, we can see project coordinator Alexa Kelley (4th from left) and the project’s interviewing team: (left to right) Treverlyn Dehaarte, Monica Parfait, Floyya Richardson, and Quanaisha Phillips. Not pictured is Annie Montilus. Photo courtesy, Crown Heights Oral History Project

And I did it. I wasn’t afraid. I was more excited than afraid, because I just felt that I was grown. And I came to New York. And to make a long story short, I came here and I had a shoebox full of chicken and biscuits. That was my lunch. And I shared it with the conductor, [who of course was a black man].

[But before the train left…,] my grandmother got on [and said a few words to him.]

She said, “You’ve got to take care of this woman. You understand?”

And he said, “I will.” And he took care of me until we got to Washington. Little did I know that in Washington, you change the trains from diesel to electric or whatever, vice-versa.

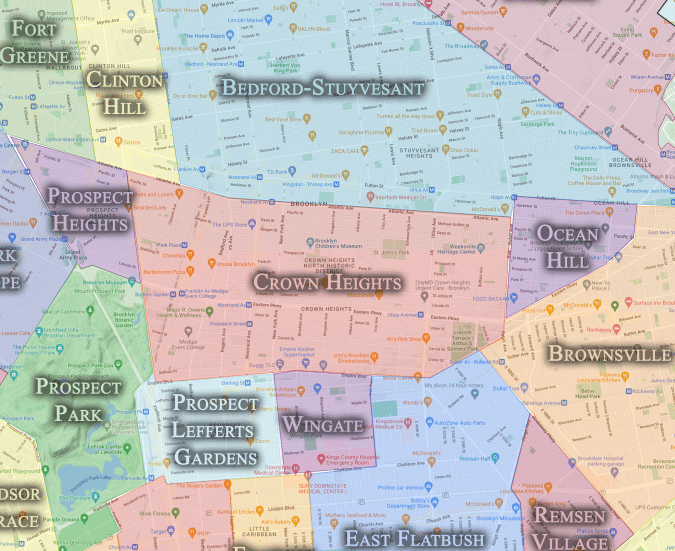

Crown Heights is located in the heart of Brooklyn. Over the course of the 20th century, the neighborhood was home to immigrants from many parts of the world– early in the century, Italian, Russian, Irish, and Jewish immigrants, among others, and later large numbers of African Americans from the South, Hasidic Jews, and Caribbean immigrants, again among others. Famous residents ranged from Beverly Sills to Audre Lorde and Jackie Robinson. Map courtesy, cityneighborhoods.nyc

But he passed this chicken serving on to the next conductor, and he took care of me from Washington to New York.

And when I got to New York, I thought my uncle or aunts would be there to meet me. But they weren’t. But I had a telephone number. So I went to the phone booth and put my dime in. And I called. And they said, “Oh, you made it.” They told me, “You are to get on a subway.”

I said, “Another subway? A train?”

They said,” “You are to tell them to tell you where to get the Independent Line.”

The Crown Heights Oral History Project’s interviews– including the interview with Evangeline Porter– are now preserved in the glorious Othmer Library at the Brooklyn Public Library’s Center for Brooklyn History.

I’ll never forget that, the Independent Line. “You are to take the A Train…. And you’re to get off there, and you’re to walk across the street and get the streetcar.” And I got a streetcar.

And she said, “You’re to get off at Kingston. You’re to get off at Kingston Lounge. It says big, up top– L-O-U-N-G-E.”

I said, “Oh God.” That’s when I started to get nervous…. I’ve never seen so many people and so much, so many houses, and so– I’d never seen all of this.

But I did it, and I got off, and I walked to their home. And they welcomed me and said, “You made it. You’re grown.”

* * *

Eunice Oden: “Like my mother raised me to be”

I found other emigrants from North Carolina in the Crown Heights Oral History Collection, too.

I wasn’t surprised: according to the U. S. Census, by the end of the Great Migration (which is usually dated 1910 to 1970), more than half of the African Americans born in the State of North Carolina lived in other states– and the largest part of them lived in and around New York City.

One of my favorite interviews in the Crown Heights Oral History Collection was with a woman named Eunice Oden, who was born on a small farm in Eastern North Carolina in 1942.

In one part of her interview, she described her excitement at coming to live with her sister in New York when she was 18 years old, and how different city life was to her life back home on the farm.

Paul Robeson High School student Treverlyn DeHaarte interviewed Ms. Eunice Oden in 2010. Courtesy, Crown Heights Oral History Project

“As a young girl, 18,” she said, “I wanted to come to New York to see what the lime lights were all about….”

She went on:

“I grew up on the farm. We had no bright lights. We had the lamps. We had pump water…. I used to go to the pump to get water, to drink, to cook, to wash with… Coming to New York it was so much different….

“And the traffic, I wasn’t used to that kind of traffic! I had never seen so many cars! I didn’t know what the subway was…, and when I got out of the subway and saw the ground, I was so happy! I told my sister, she should have told me what to expect!… I was scared!”

What struck me most in Ms. Oden’s interview was how well prepared she felt to take on her new life in New York City.

In the interview, she repeatedly explained that the values that her elders had given her back in Eastern North Carolina had remained her guiding lights in New York.

“It was a lot of teaching that my mother, my grandmother, my uncle, gave me,” she told the young woman interviewing her.

Needless to say, she was not referring to knowledge of the subway or the traffic or anything like that. She was talking about the core values that had proven central to her life: faith and family, clean living, honesty, and treating others as you would want them to treat you.

And because life in New York was not easy, Ms. Oden made one other value that her family had taught her especially clear.

“I knew what hard work was, and I never backed off of hard work…” she said. “I wanted to be independent like my mother raised me to be.”

Hardy Joe Long: “I wanted to build her a home”

At the Othmer Library, I also found an interview with an African American businessman and community leader named Hardy Joe Long. Mr. Long had left a small town in Eastern North Carolina and settled in Bedford-Stuyvesant, just north of Crown Heights, in the 1950s.

This is a very brief excerpt from Mr. Long’s interview, which describes why he was so determined to leave the town of New Bern, N. C., near where I grew up, and go to New York City.

Hardy Joe Long addressing a Brooklyn Community Board meeting in 2013. The board was weighing a proposal to rename a portion of a local avenue after his legendary record shop, Birdel’s Records. The shop had been a community institution in Bedford-Stuyvesant, the neighborhood just north of Crown Heights, for nearly 70 years. Mr. Long had been the shop’s owner since 1961. Photo courtesy, Paul DeBenedetto

These are his words:

“I grew up in North Carolina. I finished school in North Carolina, a little town they call New Bern, North Carolina…, right there on the water.

“I grew up there. I had a good foundation– from my mother, my father, my sisters and my brothers.

“When I finished high school, my vision was to help my mother. I wanted to build her a home there, because at that time we were living in what you call a small shack and I am not ashamed to talk about it today because it has really helped me.

“Because when I left North Carolina, I came to New York with a vision. I wanted to do better for myself and to better my mother’s living conditions in North Carolina—and on that point, I have achieve what my goals were.”

Mr. Long was interviewed in 2008 as part of an oral history project commemorating the Bedford Stuyvesant Restoration Corp.’s 60th anniversary. The BSRC was the country’s first community development corporation (CDC), and Mr. Long was one of the group’s longtime supporters.

Randy Mills: “Dressing up like these New York boys”

At the Othmer Library, I also found an interview with an African American gentleman who was born in North Carolina in 1930 and spent the early part of his childhood on his grandparents’ tobacco farm.

His name was Randolph “Randy” Mills– and as was the case with Evangeline Porter and Eunice Oden, high school students interviewed him as part of the Crown Heights Oral History Project.

(Mr. Mills, by the way, never said exactly where his grandparents’ tobacco farm was– he just said “rural North Carolina.”)

The students interviewed Mr. Mills in 2010, when he was 80 years old. By that time, he had retired from his job as a truck driver. He was taking great pride in his three children, and he said that he enjoyed sitting out front of his favorite shops in Crown Heights and playing dominoes with old friends.

He remembered life on the tobacco farm with great nostalgia, even though he had grown up there during the Great Depression.

He did not dwell on the hard times– and those were hard times for most tobacco farmers, but especially for black tobacco farmers. Instead, he talked about the things that he had relished on the farm that could not be found when he moved to New York City.

I might be wrong, but I have a feeling that he missed his grandfather and grandmother above all.

In this excerpt, Mr. Mills recalls the family’s tobacco farm.

“I was born in North Carolina…. Most beautiful thing in the world. You grew your own food. You didn’t have to depend on stores or stuff like that. My grandmother, she go out there and … kill a chicken.

“If we wanted pork, my grandfather had what you call a smokehouse—that’s where we would hang up the pigs after they slaughtered them and everybody cleaned them and everybody took whatever part they wanted, and the rest were hung up in the smokehouse….

“We grew our own peanuts. You had walnuts. You had pecans. You had apples. You had pears…. Figs… And we didn’t worry about no shoes. We ran barefoot and that was a good feeling, running in the sand and dirt….

“My grandfather used to grow tobacco. We’d crop tobacco and give it to the women and the woman had a pole and we put it up in the barn and after it gets dried out, they’d take it to another town and that’s where they’d sell it….”

He remembered his first day in New York City as well.

“My mother and father came first, and then they sent for my brothers and I….

“And I didn’t know nothing about no money. And the first day [I was] in New York, the man said I was stealing.

“I didn’t know that you got to buy a piece of food off the stand and everything, and I went around the corner and I saw all this food and I picked this thing up and started to eat it. And he come out there and he said I was stealing!

“I said, ‘I don’t know nothing about no stealing! What did I steal?’

“He said, `How long you been here?!’

“I said, I came in today.’

“He said, `So let me explain and talk to you’—and [after he did that], he gave me a job. That same day, he gave me a job—and he taught me about the neighborhood.

“[Wasn’t long], we started dressing up like these New York boys. Because in the country, all we wore was these dungarees and that was it.”

Sandra Gibbs Sutton: “The sisters all came to New York”

The last excerpt that I’ll quote today comes from an African American woman named Sandra Gibbs Sutton, who was also interviewed as part of the Crown Heights Oral History Project.

Like countless others, she grew up with one foot in North Carolina and the other in New York City.

Ms. Sutton came to New York two decades after the period that historians usually call the Great Migration (1910-1970). But I think I liked her interview so much because she sounds like so many young people– of all races and backgrounds– who go to New York City to escape the confines of the world in which they grew up and to find a different kind of freedom.

Sandra Gibbs Sutton (second from left) with several of the student interviewers from the Crown Heights Oral History Project at the Eastern Parkway Brooklyn Public Library, where Ms. Sutton was employed at that time. Courtesy, Crown Heights Oral History Project

At the beginning of her interview, Ms. Sutton stated that she moved to Crown Heights after finishing college in North Carolina.

“I’m originally from North Carolina, a small town maybe a thousand people…. My family—mostly my sisters—early on came to New York, because this was the place where you would get a job and kind of raise your family.

“This is what most of the members of my family did— the sisters all came to New York.

“In the summer, when I got out of school, I’d come to New York, [too]. And of course New York is such an exciting place for a young person.

“I got a [summer] job [here], starting with taking care of my sister’s kids and then, by the time I was 14, I got a real job at one of the department stores and that just opened up a whole new world for me. So I knew when I got out of high school, I knew where I was going to go! This is where it all started.”

She taught school in Brooklyn for 18 years, then took a job at a local library. She clearly relished her freedom.

“Growing up in North Carolina, you’re kind of, I don’t know, you don’t feel as secure, you don’t grow up with those same feelings that you’re empowered as a woman… You have a place. If someone is speaking as an adult, you don’t say anything….”

After she left teaching, she began working at Brooklyn’s public libraries.

“It was such a high, such a rush—to come to New York City,” she said.

“I had so much freedom…. [It was different than back home.] My mother’s mother, [and even] my mother’s mother’s mother, [lived with us back in North Carolina.] There were so many rules….”

For more on the historic ties between African American communities in Eastern North Carolina and New York City, see my 5-part series “The Sons and Daughters of North Carolina.” And of course for an overview of the Great Migration, Isabel Wilkerson’s The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration is dazzling.

I enjoyed this personal history so much. Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person