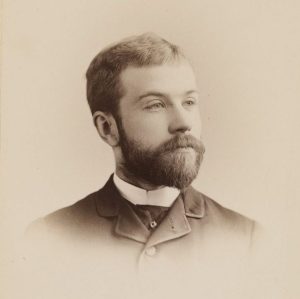

Portrait of Mary Phinney von Olhausen (1818-1902). Frontispiece from James Phinney Monroe, Adventures of an Army Nurse in Two Wars (1902)

I found the letters in an old book called Adventures of an Army Nurse in Two Wars. Published in Boston in 1902, the book chronicles the life of a Civil War nurse named Mary Phinney von Olnhausen and it caught my attention because she spent two years at Union army hospitals here on the North Carolina coast.

From 1863 to 1865, Nurse von Olnhausen cared for Union soldiers, war refugees, and sometimes Confederate prisoners of war at three different army hospitals on North Carolina’s coast.

For most of that time, she nursed the sick and wounded at a Union army hospital in Morehead City, which in those days was a small coastal village that Union troops had captured early in the war.

She later served briefly at a military hospital in Beaufort, N.C., just east of Morehead City, which was also occupied by the Union army.

Finally, in the spring and summer of 1865, von Olnhausen served at an army hospital in Southport, N.C., 100 miles to the south of Morehead City and Beaufort. (At that time, Southport was called Smithville.)

Nearly 40 years later, soon after von Olnhausen’s death, her nephew, James Phinney Monroe, shaped her letters to her family, her personal diary, and an unfinished autobiography into Adventures of an Army Nurse in Two Wars.

James Phinney Monroe (1862-1929) was an MIT professor and businessman from Lexington, Mass. Among his other books was a history of the Ursuline Convent riots of 1834, during which a Protestant mob ransacked and burned a Catholic convent in Charlestown, Mass. Photo courtesy, MIT Museum

Thankfully, James had a light touch. In telling her story, he made sure that his aunt’s writings were front and center.

He re-printed dozens of von Olnhausen’s letters in full, as well as quoted directly from her unfinished autobiography. Other than the book’s introduction and conclusion, he added only enough narrative to fill in missing gaps in those sources and to provide historical context for them.

Trusting in his aunt’s voice, James shaped an unforgettable portrait of Mary Phinney Von Olhnausen. Through his efforts, we discover a courageous woman, a pioneering nurse, and a devoted caregiver.

We also discover an eclectic and fascinating free spirit who was stubborn and defiant, prone to vile prejudices, and in battle, day in and day out, with the shackles that were placed on women in Civil War America.

As we will see, von Olnhausen was also bearing her own traumas while she cared for others. More than once, as I read her letters, I got the feeling that she only had any peace of mind at all in those moments when she had no time to rest and no time to think about her own losses and her own grief.

In this essay, I will work my way through von Olnhusen’s letters from all three of the army hospitals where she served as a nurse on the North Carolina coast.

I will not say much about her nursing career earlier in the Civil War, before she came to North Carolina. And I will only be saying a word or two about her nursing work during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, which is the other war in which she served as an army nurse.

But von Olnhausen’s letters from the North Carolina coast are more than enough.

In those letters, we see the war especially in Morehead City through a nurse’s eyes. We go into the hospital with her, and we meet the young men to whose care she gave herself night and day.

In her company, we also visit refugee camps where she is stunned by the squalor and suffering.

We meet too Rebel prisoners of war, southern Unionists, and African American soldiers. We witness the great yellow fever epidemic of 1864, and also the tragic smallpox epidemic that swept across that part of the North Carolina coast early that same year.

We hear of a massacre of black soldiers and civilians.

And in every letter, we come to know a remarkable woman whom, if you are like me, you will not soon forget.

“She Acted the Nurse and Surgeon”

I want to begin this exploration of Mary Phinney von Olnhausen’s letters by saying just a little about how she came to be a nurse on the North Carolina coast, because it is a poignant story in itself.

Mary Phinney was born at or near her family’s farm in Lexington, Massachusetts, on February 3, 1818. She was the fifth of Elias and Catherine Bartlett Phinney’s 10 children and grew up accustomed to farm work and with a strong interest in the natural world.

In the introduction to Adventures of an Army Nurse in Two Wars, her nephew James wrote:

“At a time when to be ignorant of nature was thought a sign of good breeding, she knew every flower and insect of the wood and field; in a generation whose women shuddered at a grasshopper, she used to take spiders and to give pocket-refuge to toads and snakes; in an age whose pale heroines were occupied mainly in graceful swooning, she acted the nurse and surgeon for every wound in a populous and venturesome neighborhood.”

He was speaking of women of a certain class and background, but I think that his words do give us an important sense of what his aunt was like as a child.

James goes on to say:

“Farm work, too, had the highest interest for her; and with perhaps a little, characteristic exaggeration she used to recall the many moonlight evenings on which she helped her father— that being his only leisure time—graft apple-trees until ten o’clock at night.”

In the book’s introduction, James noted that his aunt had also been “an accomplished needlewoman” and had “a marked talent for drawing” from the time that she was very young. As we will see, there were times in von Olnhausen’s life when she used those skills to make a living and maintain her independence.

Mary Phinney did not marry young, and she seems to have spent much of her early life caring for her mother and father and their home.

However, her father died unexpectedly in 1849. He and Mary had been very close. Her mother remained in Lexington, but she evidently had few savings and had to sell the family farm that Mary loved.

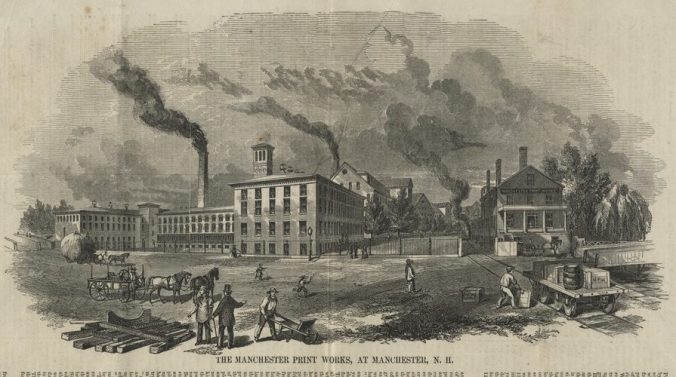

As did many New England farm women of that time, Mary Phinney found work in the textile industry. She worked first at a mill in Dover, New Hampshire, and then at the Manchester Print Works in Manchester, New Hampshire, where she was employed in the print department.

The Manchester Print Works, Manchester, N.H., 1854. From Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, 18 Dec. 1854. Image courtesy, American Textile History Museum, Lowell, Mass.

At the Manchester Print Works, she met Gustav A. Olnhausen, a German immigrant employed as a chemist in the mill’s dye-house.

Mary and Gustav soon fell in love. They were married on May 1, 1858. Finding Gustav must have been a surprise to Mary. She was 40 years old at the time.

The couple moved into a small cottage and seem to have had a happy life together, but for an all too brief time. Gustav was discovered to have a fatal disease—James did not say exactly what it was.

I assume that Mary had at least helped to nurse her father before his death, and now she nursed Gustav in his last days.

Caring for family, friends, and neighbors was the path that prepared nearly all women nurses– north and south, free and slave– for the work they did in the Civil War. There were no schools of nursing in the United States until the 1870s.

Gustav Olhausen died on September 1, 1860. He and Mary had only been husband and wife for two and a half years.

Looking back on his aunt’s life almost half a century later, her nephew James believed that Gustav’s death, for all Mary’s grief and heartbreak, “proved really to be the beginning of her life.”

They are his words, but I suspect that his aunt, in her last years, may have put them in his mouth.

In Adventures of an Army Nurse in Two Wars, James also ventured that his aunt turned outward, in a way that she most likely would not have otherwise, to cares beyond her own home, after her husband’s death.

He wrote, “That love which might have been given, had he lived, solely to her husband, was to be expended during the coming years on others.”

“My Special Calling”

Soon after the Civil War began in April 1861, Mary Phinney von Olnhausen began seeking a post as a nurse for the Union army. At first, she encountered frustrating delays, but Dorothea Dix, the Union army’s superintendent of nurses, finally accepted her in the nursing corps in August 1862.

Daguerreotype of Dorothea Dix, ca. 1850-55. By Samuel Broadbent. Courtesy, Boston Athenaeum. While she played a central role in Civil War nursing, Dix is better known as a reformer of mental health treatment in the United States. In 1856, North Carolina’s first psychiatric hospital, Dorothea Dix Hospital in Raleigh, was named after her.

She was sent almost immediately to the Mansion House Hospital in Alexandria, Virginia, which at that time was being overwhelmed by casualties from the Battle of Cedar Mountain.

In Adventures of an Army Nurse in Two Wars, her nephew wrote:

“With no experience of serious wounds and with no knowledge of nursing beyond what she had gained in her ministrations to those among her family and friends who had been ill, she was plunged, without preface, into a crowded hospital during one of the bloodiest campaigns of the Civil War.”

From von Olnhausen’s very first night, he continued:

“She was called to assist [in surgeries] performed with little or no anesthetic, by surgeons who, naturally brutal, had been made doubly so by the hurry of overwork and the magnitude of their seemingly endless task. The operating-room was literally a sea of blood, and its operators had become little better than butchers”

Von Olnhausen served at Mansion House until June of 1863. While there, she assisted during surgeries, dressed wounds, bathed patients, washed bedclothes, cooked meals, and comforted the dying.

The Mansion House Hospital, Alexandria, Va., ca. 1861-65. The Mansion House Hotel was commandeered by the Union army in November 1861 and re-opened as a 500-bed general hospital on December 1, 1861. Photo by Andrew J. Russell. Courtesy, Library of Congress

She found the work brutally exhausting, and she was infuriated at the way the hospital was run and the way patients were treated.

She considered the hospital a chaotic mess, the staff corrupt, and the Union army’s treatment of its wounded a disgrace.

Among the hospital’s male staff, she also encountered fierce resistance to the very idea of women nurses. Women had always borne the burden of nursing at home, but in the United States they had not yet been accepted in hospitals, and even less so in military hospitals.

Particularly at the beginning of the war, many army surgeons refused to allow women to serve as nurses in their hospitals.

The portion of Adventures of an Army Nurse in Two Wars that concerns Mary Phinney Von Olnhausen’s work at Mansion House Hospital inspired a TV series called Mercy Street that aired on PBS in 2016-17. The show’s plot was only loosely based on the book and did not purport to cover any of her career on the North Carolina coast.

Yet for all that, von Olnhausen found the work at Mansion House exhilarating and the most satisfying thing she had ever done.

Despite the difficulties, she still declared:

“I’m in for the war until discharged; I can’t for a moment regret it; I could never be contented now at home remembering what I can do here and how many need me. I know that all are not fitted for this life, but I feel as it were my special calling, and I shall not leave it, if God gives me strength, while I know there is a Union soldier to nurse.”

The Civil War was a turning point in the employment of women nurses in hospitals on both sides of the Mason-Dixon Line. The women proved too capable, and the need too great.

Over the course of the war, an estimated 40,000 women worked as nurses in Union and Confederate army hospitals. On the North Carolina coast, as in many other places, that number included large numbers of African American women, most of whom had been slaves before the war.

You can learn more about the history of nursing in North Carolina during the Civil War and in other periods of the state’s history at North Carolina Nursing History, an excellent website created by Professor Phoebe Ann Pollitt and her colleagues in Appalachian State University’s Department of Nursing.

Going South

The life of Mary Phinney von Olnhausen began arcing toward the North Carolina coast in the summer of 1863, when Dr. James B. Bellangee, one of Mansion House’s surgeons, was reassigned and put in charge of establishing a new Union army hospital in Morehead City, North Carolina.

Dr. James B. Bellangee, ca. 1861-63. Photo by R. A. Lewis. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Morehead City was a small coastal settlement just south of the Outer Banks. In one of the first military campaigns of the war, Union forces had captured the Outer Banks and a sliver of coastal towns and villages that included Morehead City and its neighbor Beaufort.

As Dr. Bellangee settled into Morehead City, he wrote von Olnhausen and another of the hospital’s nurses and requested that they join him.

Von Olnhausen had little patience for most of the Mansion House’s medical staff. However, she had only admiration for Dr. Bellangee. Deeply impressed by his skill and dedication, she felt as if she could not decline his offer, even though she had misgivings about Morehead City.

Above all, she feared that she might not be able to do as much good in Morehead City as she was doing at Mansion House, or that she might do in a dozen other army hospitals closer to the war’s front lines.

Since being captured by Union forces in 1862, Morehead City had been relatively quiet from a military standpoint. The settlement had not seen any military action, other than the occasional guerrilla foray.

Von Olnhausen hungered to be close to the battlefield. However, she accepted Dr. Bellangee’s invitation to go to Morehead City. She assumed that it would be a short-term posting, and that once the new hospital was established, she would move to one of the war’s theaters where she was needed more.

“Not a Reb on the Whole Island”

Mary Phinney von Olnhausen left Mansion House and sailed from Alexandria toward Morehead City in the summer of 1863.

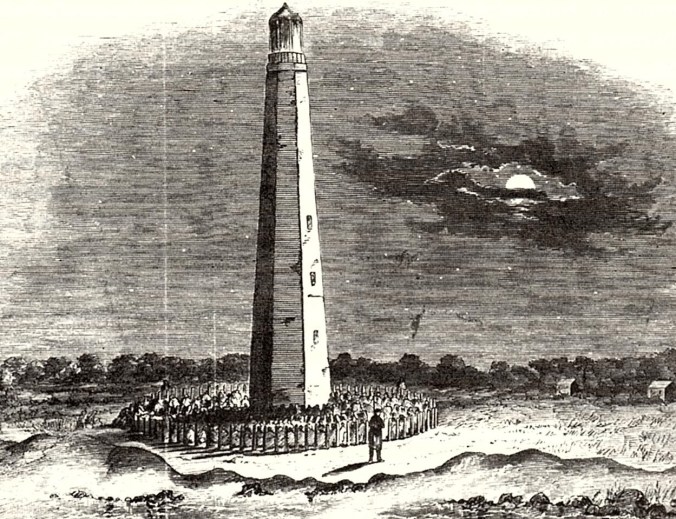

Engraving of Union encampment at Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, ca. 1862. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

In a letter dated September 13, 1863, she described her first sight of the North Carolina coast.

“Yesterday morning we got to Cape Hatteras, where we lay all day. I went ashore in the tug and wandered about as I liked. There are two forts there, garrisoned by North Carolina troops… But such a beach and such waves I never saw,– miles of it, and the breakers are fearful.”

The troops were apparently soldiers of the 1st North Carolina Union Volunteer Infantry, which was made up of white men who had enlisted in the Union army rather than fight for the Confederacy. Some came from the Outer Banks. Others came from elsewhere on the North Carolina coast.

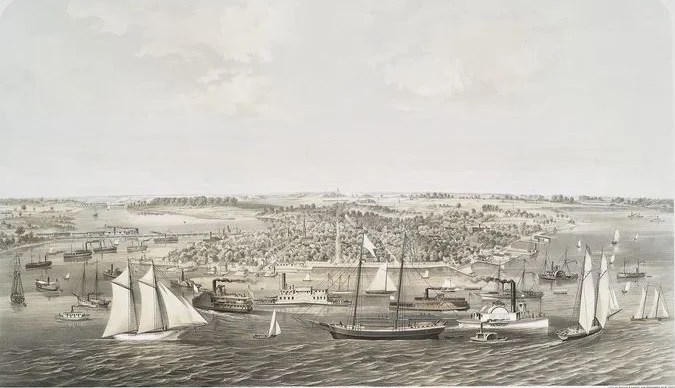

View of New Bern, N.C., looking up the Trent and Neuse River, 1864. Major & Knapp Engraving (Voltaire Combe, artist and publisher), 1864. Courtesy, New York Public Library

Sailing south from the Outer Banks, von Olnhausen’s steamer passed through Pamlico Sound and made harbor in New Bern, a seaport that was the Union army’s headquarters on the North Carolina coast.

She then took a train east to Morehead City.

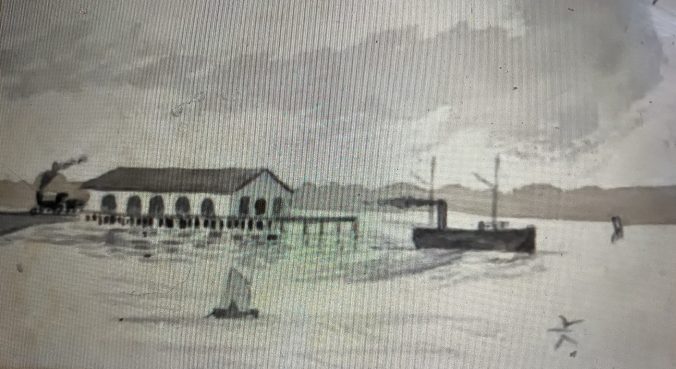

Herbert E. Valentine, ink wash of the train depot at Morehead City, 16 April 1863. From the Herbert E. Valentine Scrapbook, Special Collections and University Archives, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Va. Valentine was in Morehead City while serving in Company F., 23rd Mass. Infantry.

On her arrival, she found Mansfield General Hospital rising on the shores of Bogue Sound. From its yard, she could look south toward salt marsh and a pair of long, narrow barrier islands and the sea beyond them.

“Dr. Bellangee … had done wonders in the short time that he had been there,” von Olnhausen wrote home. “Eight barracks had been built, each containing about seventy-five beds, some of them already fitted up.”

She observed that Morehead City “was made up of about 10 houses and was the terminus of the railroad, so transportation of the wounded from New Berne [sic] was easy.”

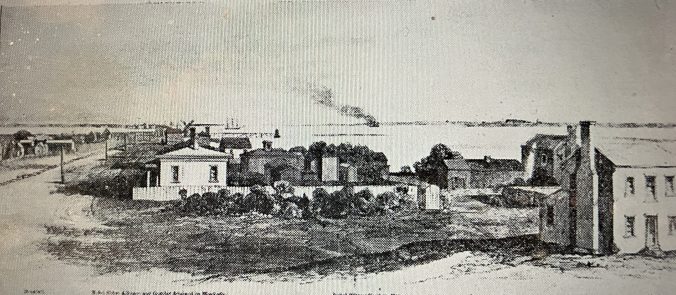

Sketch of Morehead City, 1862. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 26 April 1862. Courtesy, NC Collection, UNC Chapel Hill Library

New Bern, 30 miles west, saw far more action during the war than Morehead City. After Union forces captured New Bern, they used the town as a staging ground for raids into Confederate territory. In addition, Confederate troops twice attempted to re-take the town.

While von Olnhausen waited for her living quarters to be made ready, she began to get to know her new home.

“Most of [that] time I spent in the woods about us. The open sea is only two miles away, and the air is splendid; enough of it, too, for it blows a tempest.”

A few days later, she still only had a few patients, and she continued to have free time that she used to explore the coastline.

Only a few miles from Morehead City, another woman also nursed sick and wounded soldiers, albeit Confederate soldiers. In addition to caring for those soldiers, Emeline Pigott (1836-1919) was destined to become North Carolina’s most famous Confederate spy. Stories about Pigott were common in my family when I was growing up: she was my great-great grandmother’s sister. She and my great-great-grandfather, with whom, at one point, she was arrested, came from slaveholding families and were ardent defenders of white supremacy and slavery. Image courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

On September 28, 1863, she wrote:

“We had a very bad storm last night and looked out for wrecks this morning, but can see none. The surf sounds so grand, and … Mocking-birds are singing, and as we have had no frost yet, it’s beautifully green in the woods.”

Two weeks later, on the 12th of November, she wrote of a pleasure excursion to Shackleford Banks, one of the local barrier islands.

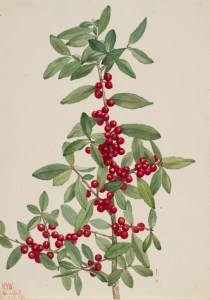

She described the islanders and their loyalty to the Union, as well as their fondness for a tea made from the dried leaves of yaupon, a kind of holly.

“They are all fishermen,” she said, “and it’s said that there is not a Reb on the whole island.”

That may well have been the case. Anti-Confederate sentiment was high in many of the communities on that part of the North Carolina coast.

On the other hand, an outward show of loyalty to the Union would not have been a bad strategy for local fishermen spying on Union naval movements for the Confederacy– and some local fishermen did just that.

Yaupon (Ilex vomitoria). Painting by Mary Vaux Walcott (1926), Smithsonian American Art Museum

In the Bluest Depths

The New Year found Nurse von Olnhausen in low spirits. Though she had made new friends and enjoyed her rambles by the seashore, she had lost all patience. She believed that she could be doing far more good elsewhere and seemed to be feeling like a racehorse confined to its stall.

In her letters, she was frustrated and downcast. Again and again, she petitioned Dorothea Dix to move her closer to the war’s front lines.

Dix preached patience and told her that her time would come.

In a letter written on New Year’s Day, 1864, we see von Olnhausen at her lowest.

“Now today I’m down in the bluest depths, cross or something, or impatient, forgetting in my willful wickedness that the good God has given me anything this past year to be thankful for … Anyway, I’m not always so desponding, thank fortune, and am sometimes singing praises all day long. Good Lord deliver me from this slough; I’m in it up the chin.”

As ever, she only seemed to find any peace at all when she had no time to think about anything other than the care of “her boys.”

A couple days later, on January 3, 1864, von Olnhausen expressed frustration again:

“For the last fortnight I have had a ward cram-full; but every one is up for discharge or furlough, and there are no more sick here; so then what’ll I do? Why can’t somebody want me and make me come?”

She meant somebody at a hospital closer to the war’s front lines.

“I … Stayed with Him Till He Died”

An incident that von Olnhausen described only a few days before she wrote that letter gives us some indication of how demanding her life was even in those weeks that she considered so slow.

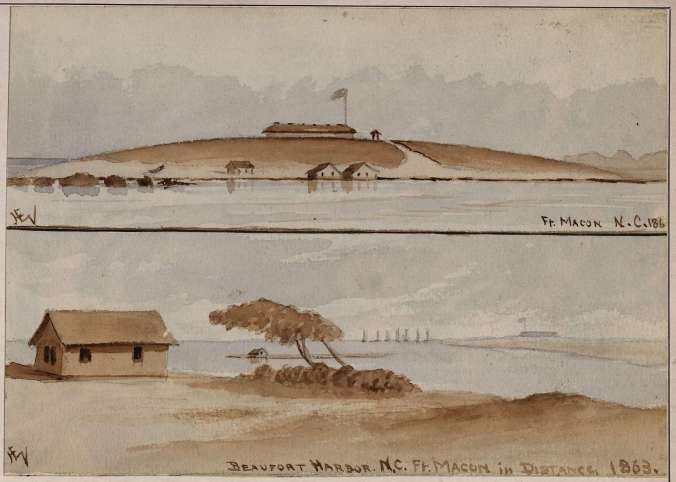

On New Year’s Eve, she attended a ball that was sponsored by the Union soldiers at Fort Macon, a fortification built in the high dunes of an island that bordered Beaufort Inlet.

Two views of Fort Macon, 1863, .evidently watercolors painted by a Union sailor or soldier. The top view is from the channel in Beaufort Inlet, while the bottom view is looking across the inlet from Shackleford Banks. Source: Records of the War Dept. General and Special Staffs, RG 165 (NA ID # 533212), National Archives

After the band played its last song, von Olnhausen discovered that a storm, already rising on her way to the fort, had gotten worse during the ball. The sea had grown so rough that she had to wait until almost sunrise before her ferry’s captain was willing to make the crossing.

“It was so stormy we could not leave till five in the morning,” she wrote in that same January 3rd letter that I mentioned above.

When her ferry finally reached Morehead City, she and another nurse still had to walk a mile along Bogue Sound to reach their quarters at Mansfield Hospital.

“It was a tough walk with gale dead ahead, and nearly blowing us off the track into the sea…”

She went on to say, “I flattered myself I’d have an hour’s sleep anyway; but just as I got upstairs they came and said F. [one of her patients] was worse. As soon as I looked at him I saw he wouldn’t live long, so just hurried off my ball fixings and stayed with him till he died, about nine that morning.”

A ball at Fort Macon was a special event, but sleepless nights and long days in the hospital were standard fare. As I read her letters, I often wondered how she could feel that she was not giving enough, and what it would have taken for her to still the restlessness within her.

“Of Course I am Tired Out”

Only a few days later, von Olnhausen’s ward did grow busier and her hours longer. On January 19th, she wrote:

“Of course I am tired out; … I have fourteen patients all in bed, ten with the worst kind of typhoid pneumonia, so they have to be lifted and fed and washed, as they can’t raise a hand. I have not left my ward, except to eat, since I last wrote.”

By the first week of February, the calm days of the previous autumn had come to seem like a distant memory. Confederate forces were laying siege to New Bern and had also attacked Newport Barracks, a Union army outpost only 10 miles from Mansfield Hospital. All was upheaval and panic.

If New Bern fell, Union army leaders expected Rebel troops to be in Morehead City within a night or two. Union troops stationed in Morehead City dug in, but there were only a couple hundred of them and nobody expected that they could hold off a Confederate assault of any size.

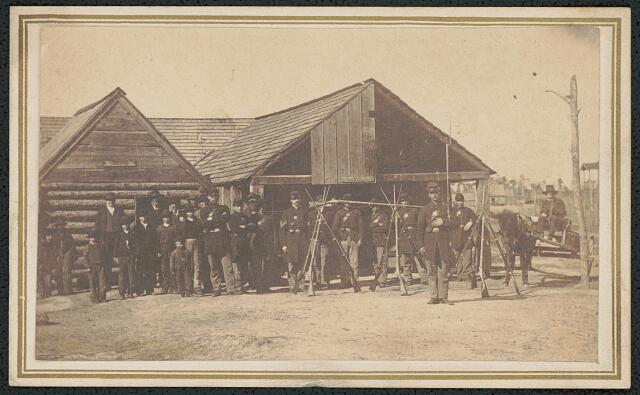

Union soldiers and civilians at the Provost Guard Headquarters at Newport Barracks, 10 miles NW of Morehead City, N.C., ca. 1862-65. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Union leaders rushed military supples, provisions, and civilians onto naval vessels in Beaufort Harbor. All braced for what they feared might come, but the hundreds of African Americans who had found refuge in Morehead City cast the wariest eyes toward the western horizon.

In a letter written on February 5, 1864, von Olnhausen described that night.

“By dark we could see Newport Barracks burning… You never did hear of such a night, I guess, as that was,– the citizen women screaming from every house, so loud that we could hear them, because their men were compelled to fight, and of course to be killed without mercy; the terrified negroes constantly arriving; the thousand reports brought in each moment; the occasional firing of a gun by some very scared sentry; and always such a rushing to and from.”

Throughout the day and that night, she would not leave the hospital.

She explained, “I utterly refused to pack or budge unless the patients went too; but, at one o’clock C. [one of the hospital’s staff] insisted on my sending my traps at least to the Fort, if I would not go myself.”

She continued:

“The moon came up, and it was such a lovely scene,– the signals from the two forts and the gunboats…, the frogs singing as if nothing were going on, and the air so warm and still. We sat for hours, and only when the morning broke went to bed. The patients had at last fallen asleep, and broad daylight found them still sleeping…. Well, the night was over, and the Rebels had not come, and everybody was quite worn out.”

The next night unfolded much the same way.

“Now here was another day and night,– constant alarms, everybody all ready for flight. Doctor gave shelter in one of the barracks to about a hundred negro women and children who had to be fed and cared for, besides the sick and tired soldiers pouring in all day…. “

“All day yesterday…,” von Olnhausen reported, “we could see fires in all directions, perhaps turpentine and perhaps homes of loyal men.”

“Still the Rebels did not come,” she recounted.

The Rebels never did come: in the end, New Bern had not fallen, and all across the countryside the fires burned out.

A Young Rebel Soldier Named Willie

By the end of February, von Olnhausen was no longer worrying about idle hands. She wrote, “I have twelve wounds to-day [sic], all I reckon, that were wounded in that bloody battle of Newport Barracks.”

Among her patients was a young Rebel soldier named Willie. He had been found with a bullet lodged in the back of his head, apparently just above his neck, at Newport Barracks.

Von Olnhausen thought it unlikely that Willie would live long. The young soldier had no illusions to the contrary, but she was still astonished at his irrepressible spirit. As best I can tell from her letters, she wholly lost her heart to him.

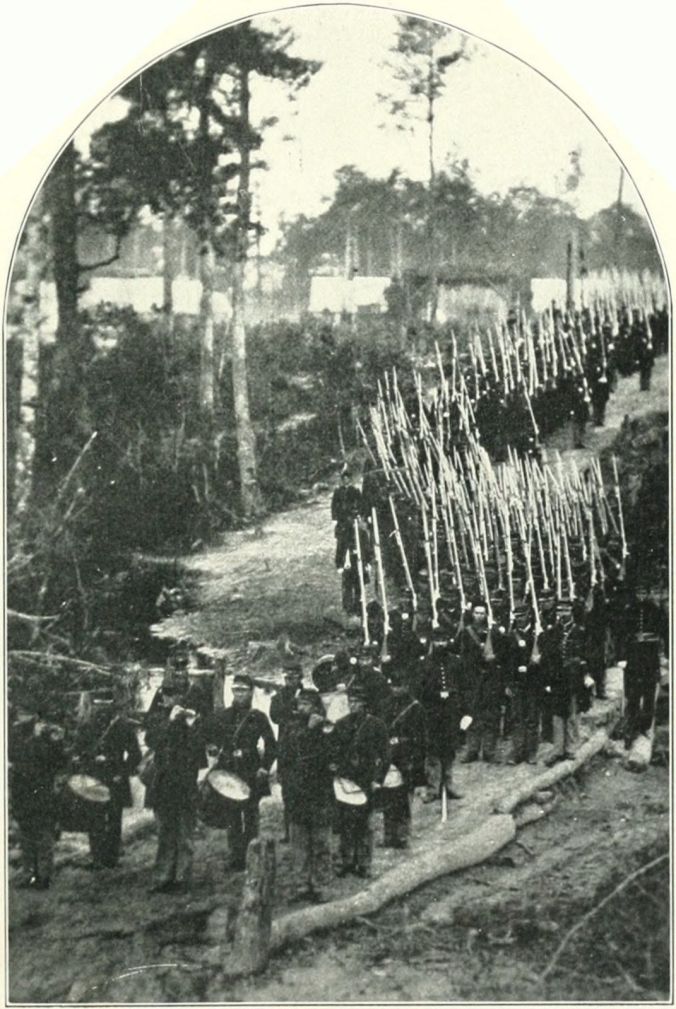

In one of her letters, von Olnhausen described how Willie laughed and joked and teased her playfully. She called him “a real character,” and she placed him in a hospital room alongside another of her favorites, a young Union soldier she called “my pet patient, Will S., of the gallant Ninth.”

Mary’s “gallant Ninth” was probably the 9th Vermont Infantry, seen here marching out of its camp at Newport Barracks in the latter part of 1863. From Francis T. Miller, ed., The Photographic History of the Civil War, 10 vols. (New York, 1911).

Von Olnhausen’s tenderness toward an enemy soldier made a deep impression on me. However, later, as I read her letters from the end of the war, I found one that revealed a very different side of herself, and not one that she was proud of.

“Bedlam Has Been Let Loose”

“For us we are full of refugees; three hundred and fifty women and children came here the day after I last wrote you, and since then Bedlam has been let loose.”

Mary Phinney von Olnhausen, May 6, 1864

Mary Phinney von Olnhausen’s life in Morehead City began a period that was even darker when Confederate troops retook Plymouth, N.C., in April 1864.

Located a hundred miles north of Morehead City, Plymouth had been in Union hands for nearly two years.

During that time, the town had become an important haven for fugitive slaves who had escaped from Confederate territory and also for local whites who sided with the Union instead of the Confederacy.

The fall of Plymouth sent shock waves throughout the North Carolina coast. And once it fell, Union commanders realized that they also could no longer hold Washington, N.C., an important riverport to the south of Plymouth.

Union army leaders quickly ordered a withdrawal of Federal troops from Washington. As they vacated their camps, they left much of the town in flames and hundreds of African Americans and white Unionists fleeing before the arrival of Confederate troops.

Before long, refugees from Plymouth and Washington began showing up in Morehead City.

In a letter dated May 6, 1864, von Olnhausen wrote of the white civilians who had sought shelter there:

“You cannot know anything of squalor till you see these people, all piping and chewing and crying everlastingly…. I never knew anything of war horrors; you should see and hear them to believe. Some of these women’s husbands have fallen into the Rebels’ hands; of course they are murdered, as not a North Carolinian has escaped, they say.”

Of the refugees, von Olnhausen wrote, “They occupy two big barracks; some of them have not a change of clothes. They had only an hour’s notice to quit Washington.”

Among their stories, the refugees told of a Confederate massacre of African American troops and civilians in Plymouth.

“You have already seen how the Rebels treated the Negroes [apparently a reference to an earlier letter that was lost]; the men were marched out in squads, made to dig their own graves, and then murdered and thrown into them, one at a time. I saw a man yesterday who saw it.”

She was referring to the “Plymouth Massacre,” one of the war’s atrocities that only recently has begun to receive official recognition.

During a recent commemoration of the Plymouth Massacre, local Junior ROTC cadets joined with the 35th U.S. Reenactors Colored Troops, of New Bern, N.C., and the 2nd Regiment, U.S. Colored Light Artillery, Battery B, of Wilmington, N.C., to honor the African American soldiers who fought and died in Plymouth in April 1864. (Photo by Sharon C. Bryant)

(You can find an address that I delivered at a recent commemoration of the Plymouth Massacre here. )

What von Olnhausen heard was secondhand, and of course we must always be cautious about taking secondhand reports at face value. Nonetheless, in this case, that account– the one she heard– is consistent with eyewitness descriptions of what happened in Plymouth.

“Not a Single Person in the World”

At Mansfield Hospital, von Olnhausen’s ward grew more crowded with the arrival of the refugees from Plymouth and Washington, some of whom evidently were in need of medical attention.

Von Olnhausen, however, had taken on another responsibility as well. She had accepted the duty of caring for three of the refugees who had no one else to look after them.

All were young children. “The oldest, a girl, is blind, and so ignorant and forlorn,” she wrote in a letter of May 6. She described the girl’s two younger brothers as “really pretty,” but said that all three were “the lousiest, dirtiest, raggedest little things you ever saw.”

The children’s mother and a new baby had died a few days earlier, apparently in childbirth. Their father was nowhere to be found; at the time, he was serving in the Second North Carolina, one of the two white Union regiments recruited on the North Carolina coast.

Thousands of African Americans, most of them former slaves, also enlisted in the Union army and navy on the North Carolina coast. From Vincent Colyer, Brief Report of the Services Rendered by the Freed People to the United States Army in North Carolina: in the Spring of 1862 after the Battle of Newberne. (New York, 1864).

The father’s status was far from clear. The Second, never very fit, had had a disastrous couple months, including the hanging of 22 of its soldiers by Confederate forces in Kinston. The father’s whereabouts seem to have been unknown, and the children, now motherless, were on their own.

Von Olnhausen wrote, “They had not a single person in the world to take care of them, not a bed to sleep on.”

Von Olnhausen took in the children and looked after them. She seems to have wholly lost her heart to them. But in another of her letters, dated only three months later, she makes it seem as if the children were among the staggering number of the war’s civilian casualties.

Her words are not exactly clear, but in that letter von Olnhausen seems to say that all three children had died that summer.

She does not give any other details. She had evidently provided them to her correspondent previously, but in a letter that is not included in Adventures of an Army Nurse in Two Wars.

If I am reading her letter correctly, the children contracted smallpox, measles, or one of the other infectious diseases that were so prevalent in the local refugee camps at that time.

In that letter, dated August 22, 1864, von Olnhausen did not try to hide the bitterness that she felt about her correspondent’s apparently ham-handed efforts to describe the children’s deaths as somehow being merciful.

She wrote, “You are real comforting in saying it’s fortunate my children all died, when I mourned so for them. You can’t know how I missed Franky; he was such a dear little boy.”

Of the refugees from Plymouth and Washington, von Olnhausen wrote:

“You ask what has become of all those people. They are scattered about in tents and shanties and live not half so good as pigs. I came across one woman yesterday, in my walk, who was living with her daughter and granddaughter under a quilt spread over a pole….”

For von Olnhausen, the war had become one heartbreak after another, too many to count, with no time to grieve one loss before the next.

“It will either harden me to stone or else take away every bit of selfishness from me,” was all she could say.

“The Tale of Suffering”

The death of von Olnhausen’s wards was a kind of tragedy that grew all too familiar on the North Carolina coast in 1864.

In New Bern, Beaufort, and, to a lesser degree, Morehead City, the autumn of 1864 was later remembered above all as a time of plague.

Von Olnhausen first mentioned the outbreak of disease in a letter of September 18th, when she reported that rumors of yellow fever in New Bern had reached her in Morehead City.

“Some say it is the yellow fever and some that it is congestive chills; anyway it is alarming, as so far all have died in a short time after being taken. I only half believe the stories, but everyone who comes down [from New Bern to Morehead City] seems tolerably frightened.”

She added, “If it should prevail to a great extent, of course it is my duty to go there, and I suppose I shall.”

Her old friend Dr. Bellangee left Mansfield Hospital to assist the local and military physicians in New Bern. By the time he arrived, some of the physicians had already died of yellow fever. Others would die soon, and Dr. Bellangee was not in New Bern long before he fell ill himself.

Engraving of an African American nurse in New Bern, N.C., ca. 1862-64. Most nurses in Union army hospitals below the Mason-Dixon Line were probably African Americans. That was likely true as well of Confederate hospitals, where the black nurses were enslaved men and women forced to care for those who fought to keep them enslaved. Engraving from Vincent Colyer, Brief Report of the Services Rendered by the Freed people to the United States Army in North Carolina: in the Spring of 1862 after the Battle of Newberne. (New York, 1864).

In a letter written on September 28, 1864, von Olnhausen reported that Dr. Belangee had contracted yellow fever while in New Bern. He was sent back to Morehead City and put under her care at Mansfield Hospital.

For the next two weeks, she worked feverishly to save him, as well as to tend to a growing number of other yellow fever victims that had been transported from New Bern.

On September 30, von Olnhausen wrote, “Doctor was very sick all day, and I could not leave him for a moment.”

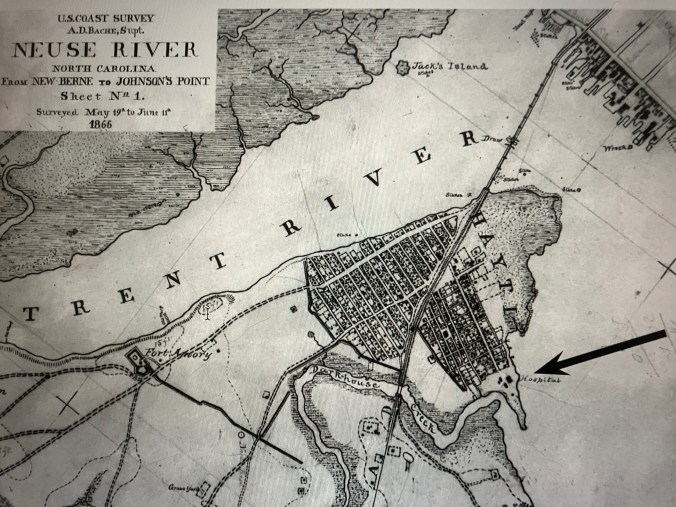

A devastating smallpox epidemic also hit the New Bern area in 1864. This map shows James City (called “Hayti” here), an African American refugee camp just across the Trent River from New Bern. Early in 1864, Federal authorities established a special smallpox hospital there specifically to treat African American refugees who contracted the disease. According to the New Bern Historical Society’s historian Claudia Houston, that hospital by itself employed at least 44 nurses, half women, half men, all or nearly all of them former slaves. They had their work cut out for them: that February an average of 50 African Americans a week had died of smallpox in and around New Bern. You can find Ms. Houston’s stellar research on the hospital here. Map source: US Survey Map T-1031 (reprinted from Ms. Houston’s article).

She worked hard to lift the spirits of the yellow fever victims, but she described an overwhelming sense of hopelessness among them.

“Nothing else approaches it except cholera,” she lamented.

“The agony of the patient, and his consciousness of the danger add so much to the horror. No one expects to live, and when the black vomit comes that look of despair … makes your heart just full.”

Von Olnhausen observed that the yellow fever epidemic hit the residents of the refugee camps hardest.

“The poor refugees die with it on short notice. Those all-suffering people have had more than their share—measles, small-pox, worms, and now fever; not many will be left to tell the tale of suffering by the time winter is over.”

The news from New Bern grew worse.

On October 2, 1864, von Olnhausen wrote:

“Friday and yesterday each there were twenty-five burials, all of yellow fever. Whole families are found dead in their houses; four were found yesterday, the wife lying across the feet of her dead husband, and both children dead beside them.”

Three days later, she confessed:

“The news from New Berne [sic] grows worse each day, and sick men are continually being brought here; but I have not time to look after those in my ward now; Dr. Belangee claims me first and all.”

Dr. Belangee died a few days later.

“He suffered constantly, notwithstanding quantities of chloroform, till three in the morning, when he died; his screams will never be forgotten,” von Olnhausen wrote on October 14, 1864.

The list of people she loved and lost kept growing. Of what it took out of her, and what unseen hurts it left within her, she did not speak.

“This Sorrowful Place”

Von Olnhausen’s grief was profound, but the grief of Dr. Belangee’s wife was of course beyond measure.

In the days after Dr. Belangee’s death, von Olnhausen helped his wife pack and move out of her quarters in Morehead City. She then carried her to the Union vessel that would take her, in von Olnhausen’s words, from “this sorrowful place.”

As they waited by the wharf, von Olnhausen penned what would be her last letter from Morehead City for some time.

“Don’t feel anxious,” she encouraged her correspondent, who in this case, as most others, was probably her mother or one of her sisters. “I am perfectly well with the exception of being tired, and [I] am really glad to be where I can make comfort to so many.”

Within days, she contracted yellow fever, fell gravely ill, and nearly died. After passing through the worst of it, she was sent home to Massachusetts to restore body and soul under the care of her family.

Many nurses did not recover from the diseases that spread across the North Carolina coast during the Civil War. This is a portrait of Carrie E. Cutter, a 19-year-old Union army nurse who died of typhoid fever in New Bern in 1862. For more on Cutter, see Claudia Houston’s excellent biography of her that was published by the New Bern Historical Society on March 13, 2022. Image courtesy U. S. Army Heritage and Education Center

“I Can’t Be Good”

The last letters that von Olnhausen wrote from the North Carolina coast concern the final months of the Civil War and the turbulent first few months after the Confederacy’s surrender.

After regaining her strength, she returned to Morehead City in December 1864. Only a month later, Union naval vessels began delivering casualties from the Battle of Fort Fisher to Mansfield Hospital.

Fort Fisher was a Confederate fort at the mouth of the Cape Fear River, some 100 miles south of Morehead City.

The fort was critical to the Confederacy because its guns protected Wilmington, N.C., the last seaport anywhere in the breakaway states that was still open to international shipping.

Bombardment of Fort Fisher prior to the ground assault of January 15, 1865. Engraving by T. Shussler based on an artwork by J.O. Davidson. Published in Robert Underwood Johnson, Battles and Leaders of the Civil War (1887). Courtesy, U.S. Naval Historical Center

In the first days of the new year, von Olnhausen’s letters sound oddly exuberant. After hungering so long to be closer to the front lines, she seems to have felt that she was finally where she was needed most.

In a January 9, 1865 letter, she could not contain herself: “Happy! Two hundred wounded and I the only wound dresser in the ward; they are just arriving. I shall have all I can do now…!”

In that letter, von Olnhausen also showed a side of herself, the one I mentioned earlier, that few would find commendable and that many, then and now, would find unforgivable.

At that time, her ward was overcrowded with casualties. Most of her patients were likely wounded sailors from the Union navy, but they also included at least some Confederate prisoners of war.

Speaking of the Confederate prisoners on her ward, Mary wrote:

“The Rebels make me so mad, and are so presuming, too. It was always `Madam, will you look at my wound?’ Now I didn’t want to see their wounds, unless they were going to die from them….

“I can’t be good, and it makes me furious to see them treated just as well as our men. The only way I could spite them was to give them one less blanket than ours had.”

By the time von Olnhausen withheld those blankets, she had to have been exhausted. She had been caring for the sick and dying for a year and a half, and in those first weeks of January, if she slept nights at all, it was very little.

She had nursed young men, barely more than boys, who had lost arms and legs, who were blinded, who were shell shocked, who would never make it home to the people they loved.

Something seems to have broken in her, as it had in countless others during that horrible war.

She knew that Dorothea Dix had a strict policy requiring her nurses to treat Rebel and Yankee soldiers alike. But in her letters, von Olnhausen made clear that she did not need Dix to guide her conscience; she knew that it was wrong to neglect or shortchange any patient.

Her own better self told her that. She confessed that she was ashamed of her behavior and, in one letter, even called herself “wicked.” Yet at the same time, she seemed resigned to the fact that she did not have it in her to be any different.

As the war neared its end, the affection that von Olnhausen had for Willie, the young Rebel soldier with whom she was so tenderhearted, had come to seem like a memory from another lifetime.

The Guns of Fort Macon

As the war neared its end, the Union army shuttered Mansfield General Hospital. Von Olnhausen hated to go. She had turned her quarters into a cozy refuge from the war’s ills with a garden, a small menagerie of pet songbirds, and a host of beach shells and other mementos of her time at the seashore.

She was also proud of her work at the hospital. Through unstinting determination, she had made her ward into an exhibit of professional nursing in which she took great pride.

As Mansfield closed, von Olnhausen was transferred to another army hospital just across the Newport River in Beaufort.

Mary was bound for Hammond Hospital, the Union army’s hospital in Beaufort, N.C. Operated by a Catholic order called the Sisters of Mercy early in the war, the hospital occupied a former seaside hotel from 1862 to 1865. In this photograph, we see another of the hospital’s nurses, a Union soldier named Horace K. Ford (far right), who first came to Hammond as a patient in 1863. Here he is posing with his brothers back home in New Hampshire long after the Civil War. From the Horace K. Ford Papers, Southern Historical Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill.

She was not fond of Beaufort. In a letter dated February 9, 1865, von Olnhausen had described the old fishing town as “such a fleay, dirty-smelling hole, and full of Secesh and rum-holes, and gambling of all kinds….”

That spring, in the war’s last days, she found the town even worse. There was no room to breathe. Refugees were everywhere. Confederate deserters, hucksters, war profiteers, and charlatans of many stripes, all eager for the spoils of war—were also everywhere.

Rushing to get supplies from ships in Beaufort Harbor to Sherman’s army, Union quartermasters bullied one and all, at least in von Olnhausen’s eyes.

Then the Confederacy surrendered. At least in her surviving letters, von Olnhausen barely mentioned the Union victory.

She did however mention Lincoln’s assassination. “I can think of nothing else,” she wrote on April 21, 1865.

Weary beyond weary, she added, “Oh, dear, when will the end come and what will it be? I begin so to long for peace and to be at home.”

On the day of Lincoln’s funeral, von Olnhausen heard the guns at Fort Macon being fired in honor of the fallen president. The shots rang out every half hour, the thunder of the cannons echoing across the sea.

“Imagine These Millions of Men … Brought Back to Chains Again”

Soon after President Lincoln was laid to rest, von Olnhausen was transferred again. This time she was sent to a new army hospital in Smithville, N.C. (now called Southport), just across the Cape Fear River from the little that remained of Fort Fisher after the Union bombardment.

Long a base for the river’s pilots, Smithville was just downstream of a vast, sprawling landscape of swamplands and slave labor camps.

With the Union’s victory, the gates of the camps had finally been opened. When von Olnhausen arrived, thousands of liberated souls were getting their first taste of freedom: searching for loved ones, building new lives, and preparing for the dangers that lay ahead.

Von Olnhausen hoped that Smithville would be a relief from the turmoil in Beaufort, but that was not the case.

With the war over, military discipline had frayed. The War Department’s plans for the hospital seemed to change almost daily, and war refugees, Union troops, and Rebel soldiers returning home all crowded the village.

Eager hands, ready to work as hospital attendants, were almost impossible to find. “All they think of is getting home,” von Olnhausen wrote.

On May 21, 1865, six weeks after the Confederacy’s surrender, von Olnhausen reported, “We have about 400 patients here, mostly recruits and bummers,” bummers being a term for foraging or marauding soldiers.

One and all were homesick, she wrote, and most were just waiting, or at least praying, to get well enough to go home.

Nothing in Smithville seemed right to von Olnhausen. She described Rebel soldiers returning home, some of them declaring that the South was not really defeated and that slavery was not dead and would rise again.

No less disheartening, a brigade of Union soldiers rampaged through the village, drinking and pillaging.

“A greater set of scalawags never lived,” von Olnhausen fumed, in an undated letter probably sent sometime in June or July 1865.

“I never heard of such men; they broke into houses, smashed ever so many heads, insulted women, stole horses and everything else they could steal…. They were drunk and rowing all the time, and everyone had to go armed.”

She kept a double-barrel shotgun close at hand, and it was not the defeated Rebels that concerned her most.

Contemplating the Confederate soldiers speaking of slavery’s return, von Olnhausen could only hiss, “Imagine these millions of men who have been fighting for their freedom brought back to chains again!”

“True Soldiers and Good men”

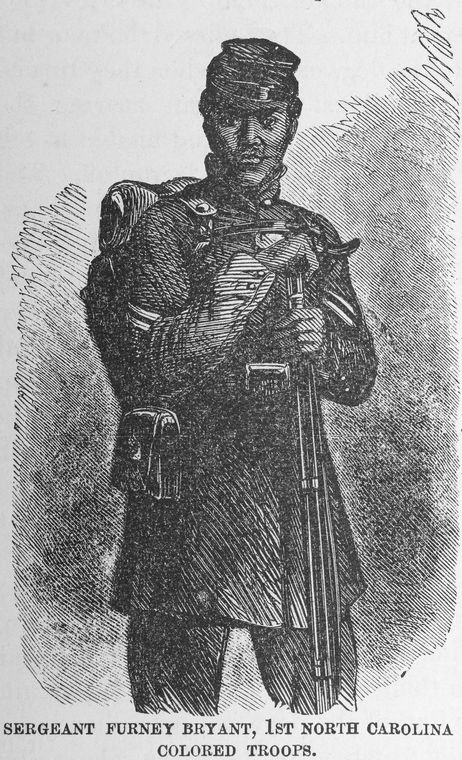

In von Olnhausen’s letters, she also observed that 500 African American Union soldiers were in Smithville, waiting for their discharges. They were apparently part of the Second Infantry Regiment, United States Colored Troops, better known as the “Second Maryland.”

Of them, Mary wrote:

“They are a splendid set of men, have always been at the front, and are so much better disciplined than the white soldiers who are here. One who stands guard at my house has had five bullets through him, and yet has lost only three months and never had a furlough; he is such a manly fellow, says his old father in Baltimore told him and his two brothers never to come back to him unless they had proved themselves true soldiers and good men.”

That was not the first time that von Olnhausen had referred to African Americans in her letters. It was, however, the first time that she did so without disdain or a tone of racial prejudice in her voice.

Von Olnhausen never seemed to have kind words for the African Americans with whom she worked at Mansfield Hospital. She seemed especially ill at ease with black women who refused to be deferential to her.

She also rarely mentioned the black Union soldiers and sailors who passed through Morehead City or the black refugees who sought shelter in and around the little settlement.

Neither did she seem to notice the flurry of black political organizing that was occurring on that part of the North Carolina coast.

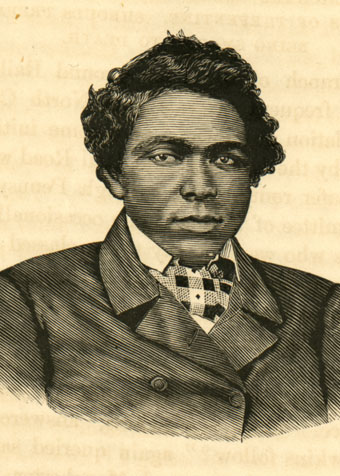

While von Olnhausen was in Morehead City, for example, African American refugees organized the Abraham Galloway Equal Rights League, one of five chapters of the National Equal Rights League that black activists established on the North Carolina coast to fight for political equality and racial justice.

In the last weeks of 1864, African American men and women in Morehead City chose to name their chapter of the Equal Rights League after Abraham H. Galloway, the subject of my book The Fire of Freedom: Abraham Galloway’s Civil War. Image from William Still, The Underground Railroad… (Philadelphia, 1872).

In her letters, von Olnhausen also never acknowledged the courage and daring of the African American refugees who had escaped from Confederate territory, or their new churches or schools. Nor, until that letter in Smithville, did she show any appreciation for what the war meant to them.

I am not sure what made von Olnhausen look at the black Union soldiers in Smithville in a different light. I only know that it is the only time in all her letters that she seems actually to have seen the African American people around her.

After the Civil War

Mary Phinney von Olnhausen’s last letter from the North Carolina coast was written in Smithville on August 28, 1865. It had been four months since Appomattox. The army hospital in Smithville was closing, and her last patients were bound for home or at least to hospitals closer to home.

Von Olnhausen was headed home, too. She wrote her family, “Soon you won’t have my scribble to decipher, but will have me chattering.”

As I finished that chapter in von Olnhausen’s life, I remembered the words of her nephew James about her husband’s death in 1860. However horrible, he had said, the loss of her husband had been “the beginning of her life.”

And it was true, Gustav’s death had started her down a different path, and she had never gone back.

After the war, von Olnhausen first attended to a family obligation. She came to the aide of one of her brothers who was homesteading on the Illinois prairie. His wife had died during the war, and he was raising four young children on his own. Von Olnhausen stepped into the void.

She remained in Illinois for several years, but in 1870 she left the country and crossed the Atlantic to serve as a nurse in the Franco-Prussian War.

Returning to the United States in 1873, she carried a medal that the King of Prussia had given her for courage and heroism.

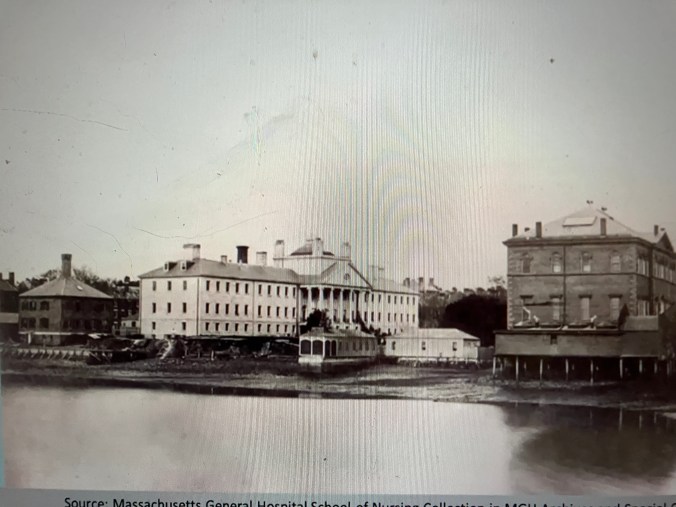

Back home in Massachusetts, von Olnhausen served briefly as one of the first superintendents of the Boston Training School for Nurses, which was modeled after the teachings of Florence Nightingale and which was one of the first nursing schools in the United States.

Established by the Women’s Education Association of Boston, the school was the forerunner of the Massachusetts General Hospital School of Nursing.

In 1873, the students at the Boston Training School for Nurses did their clinical work in a building called The Brick (far left in this photograph), which was behind the Massachusetts General Hospital’s Bullfinch Building (center). Harvard Medical School, best known (at least in my household) for being the alma mater of my wife Laura, is on the far right. Courtesy, Massachusetts General Hospital Archives and Special Collections

Evidently, the school’s trustees discharged von Olnhausen after 10 months, pleased with her knowledge of nursing but far from satisfied with her performance as a teacher and administrator.

I found the information on Mary Phinney Von Olnhausen’s tenure as the school of nursing’s superintendent in a 2023 paper by Mary E. Larkin, Susan Fisher, and and Kenneth White called “Nursing Education Transformed: A Closer Look at Establishing the Boston Training School for Nurses in 1873.”

Von Olnhausen later served as superintendent of a Staten Island maternity home that was a refuge for mothers who were either unwed or seeking refuge from abusive husbands or fathers.

She left the field of nursing sometime later in the 1870s. For many more years, she relied on her talents for drawing and embroidery to make a living.

Remaining in Boston, she was able to remain independent, in her nephew James’ words, by “producing beautiful designs and exquisite embroideries and teaching others how to make them.”

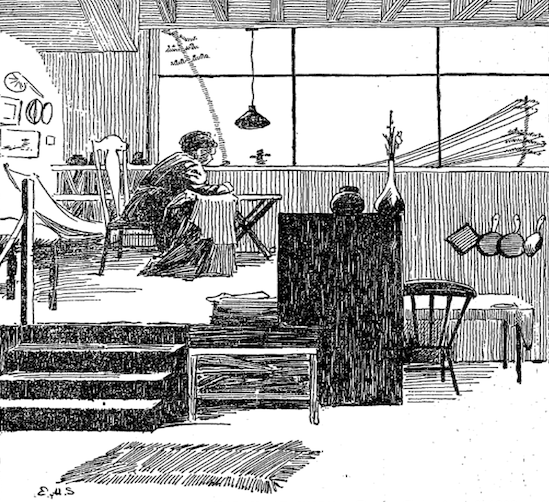

An artist’s drawing of Mary Phinney Von Olnhausen at Grundmann Studios. Located next to MIT, the Studios housed the Boston Student Art Association, craft and art workshops, and Copley Hall, where art exhibits, lectures, and other cultural events were held. She was 79 years old at that time. Boston Globe, 9 April 1899.

For much of that time, and possibly until her death in 1902, at the age of 84, von Olnhausen resided in what a Boston newspaper called “a Bohemian colony,” a collection of women artists’ and craftswomen’s studios of which she was evidently the matriarch.

According to her nephew’s account in Adventures of An Army Nurse in Two Wars, von Olnhausen corresponded with old friends on the North Carolina coast late into her life. At least one winter, she also returned to Morehead City.

That winter, her nephew said, she had made the journey back to the site of Mansfield Hospital, then taken a ferry to Shackleford Banks, the remote barrier island that she had visited during the war.

At that time, before the great hurricanes of the 1890s, Shackleford was wild and beautiful like it is now. But unlike now, it was also still home to two or three wind-swept little settlements where the people seemed to take everything they needed from the sea.

That winter von Olnhausen made her camp on Shackleford, as I have done myself over the years, and walked the shoreline.

I will always think of her there, by then an old woman with her memories of war and lost loves and so much else, walking on the beach beneath the endless stars, listening to the roar of the ocean waves.

-End-

What a woman I can’t believe how persistent she was and eager to learn and change the prejudicial ways go girl

LikeLike

Merry Christmas My mom and I sure are enjoying your baking skills

LikeLike

David, this was masterful! Thank you. It filled in a number of gaps for us. I write from NC as we are spending another winter here. Plans to move to VT were aborted by Paul’s asap need to have open heart surgery. Thankfully his VT cardiologist flagged the problem and surgery was done at Dartmouth Hitchcock in mid-Sept. He recuperated in VT until it was too cold. All went well and he is thankful he is not as tired as he was. So, we aim again for a spring move.

Our very best wishes for the holidays. I have been making pussy hats for all my tiny grand nieces (and others). It is one option to cowering under a bunch of quilts during the New Year. Susan Susan DeWitt Wilder 207.730.0574 Davis, NC and Perkinsville, VT

LikeLike

You have outdone yourself. There is enough here for three novels, a fascinating and tangible history. Thank you

LikeLike

You have outdone yourself. There is enough here for three novels, an inspiration. I love how you give so much connected detail, not just the main story of the nurse but everything going on around her at the same time and related stories. Thank you for doing what you do – Jessi Waugh

LikeLike

David,

My name is Edgar Toms Carr. Are you familiar with my Great Grandfather, Robert Watson Winston’s autobiography titled… “It’s a Far Cry”?

I ran across your name looking for the location of the herring fishery that he describes in his autobiography. He was the youngest of the family born 1860, raised in Windsor, NC but weathered the Civil War in Franklin County at their retreat home titled… Avoca.

Edgar Carr

919-906-2496 c.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Edgar, It’s very good to hear from you. I’m afraid I’ve never read your great-grandfather’s autobiography, though I’d very much like to. As for the location of the fishery, I can’t swear this is right, but I always thought that the Winston family’s fishery was called Terrapin Point and was located on the north side of the Cashie River’s mouth– where it’s entering Bachelor Bay on the Albemarle Sound. As I understand it, Terrapin Point was a little more than 1/2 mile east of where Cashoke Creek enters the Cashie. If you haven’t already found them, you might take a look at the photographs in my little photoessay called “The Herring Workers”– it includes a few photographs from the Terrapin Point Fishery in the 1930s that might interest you. https://davidcecelski.com/2021/02/24/the-herring-workers/ I hope this helps a bit! All best wishes, David

LikeLike

David,

Thank you for responding!

I would like to get a copy of “It’s a Far Cry” to you.

How best?

Edgar Carr

LikeLike

You are too kind, Edgar, but I can’t say no to your generosity! I prefer not to make my mailing address public here, but if you email me at david.s.cecelski@gmail.com, I’ll send you my address! Thank you again! David

LikeLike

I finally read this article. I think this is one of the best that I’ve read. Maybe because it mirrors my nursing profession somewhat.David, this sound like a documentary or perhaps a movie. Your writing is exemplary of her story.Is her nephew still living? I am waiting to see the next article. The unveiling of the marker went over without any hitches. Thank God! We missed your presence but I understood.Thank you for all you do to bring attention to the lesser known history of Eastern North Carolina. Rosie

Yahoo Mail: Search, Organize, Conquer

LikeLike

Thank you Rosa! I’m so glad you liked the story! I have something else I’d love to get your advice on– related to the history of Piney Woods, Plymouth and the old fisheries on the Roanoke River! I’ll call you!

LikeLike