The Nine O’Clock Whistle is the collective memoir of three remarkable African American women who were part of the civil rights movement in Enfield, N.C., in the 1960s.

Foreword to The Nine O’Clock Whistle

The Nine O’ Clock Whistle is the story of the civil rights movement in the small town of Enfield, North Carolina.

It is the memoir of three extraordinary Black women, told, one by one, in their voices: first, Willa Cofield’s, then Cynthia Samuelson’s, then Mildred Sexton’s. Their story is an important, untold chapter in the African American freedom struggle, and it is deeply moving, gracefully rendered, and utterly unforgettable.

Willa Cofield is now 95 years old. She has had a long and accomplished life as a scholar, teacher, and human rights activist. During the 1960s, she was a high school teacher in Enfield and gave herself heart and soul to the African American freedom struggle. She was fired for her activism in 1964, and the federal lawsuit that she filed to challenge her dismissal was a landmark moment in America’s civil rights movement.

Willa Cofield, teacher, community activist, documentary filmmaker, and co-author of The Nine O’Clock Whistle. Courtesy, University Press of Mississippi

Cynthia Samuelson and Mildred Sexton were two of Willa Cofield’s students at Inborden High School in the early 1960s. They grew up in Enfield during the Jim Crow Era and joined the civil rights movement there when they were teenagers.

Cynthia Samuelson, a former student of Willa Cofield’s, a long-time IT specialist with both the federal government and in the private sector, and a co-author of The Nine O’Clock Whistle. Courtesy, University Press of Mississippi

Like Dr. Cofield, their mentor and now dear friend, they seem to remember every little detail of life in Enfield. Whether it is the lilt of the people’s voices, the dust on the streets, a child’s first solo at church—or Cofield and her 5-year-old daughter standing on a front porch and watching a 17-foot-high cross burning, unflinching and undaunted— it is all here. In the pages of The Nine O’ Clock Whistle, a whole town, a whole age, a people’s whole struggle for freedom, comes to life.

Mildred Sexton, also a former student of Willa Cofield’s, a public schoolteacher for 43 years, and a co-author of The Nine O’Clock Whistle. Courtesy, University Press of Mississippi

I have been a historian of America’s civil rights movement for most of my life, but I still found The Nine O’ Clock Whistle revelatory. The story of this grassroot struggle for freedom and justice has never been told previously, and indeed the saga of black activism in the broad swath of Black Belt counties that make up northeast North Carolina is largely unchronicled and, in most cases, forgotten. It is one of the most conspicuous gaps in our understanding of the civil rights movement across the American South.

Many students of history will know that Ella Baker grew up only 25 miles from Enfield, and several historians, including myself, have made passing reference to the Halifax County Voters Movement.

But that is just the tip of the proverbial iceberg. In the 1960s, civil rights organizers who visited that part of North Carolina often compared its oppressiveness and fierce resistance to black civil rights to what they had encountered in the Mississippi Delta and other parts of the Deep South. Thanks to these three women, at least the story of the civil rights movement in Enfield will not be lost.

The Nine O’ Clock Whistle is a book that speaks to our intellect, but also to our hearts. Indeed, there are moments in these pages that have gotten so deep under my skin that I believe that I will always carry them with me. I cannot imagine, for instance, ever forgetting Mildred Sexton’s richly textured narrative of Enfield’s African American neighborhoods when she was a girl. As she guides us through the streets, you can breathe in the sense of community, the safety she felt there, and the love she received there.

Principal Joseph Wiley greeting a school bus at Willa Cofield’s alma mater, the Brick Tri-County High School, ca. 1940. Now the Franklinton Center at Bricks, a social justice retreat center, the school was located a few miles outside of Enfield, N.C. Photo courtesy, Amistad Collection

I found other scenes in The Nine O’ Clock Whistle unforgettable in a very different way. How can one ever forget the civil rights gathering where Inborden High’s students erupted in what seemed like a never-ending chorus of “We Shall Overcome” and other freedom songs?

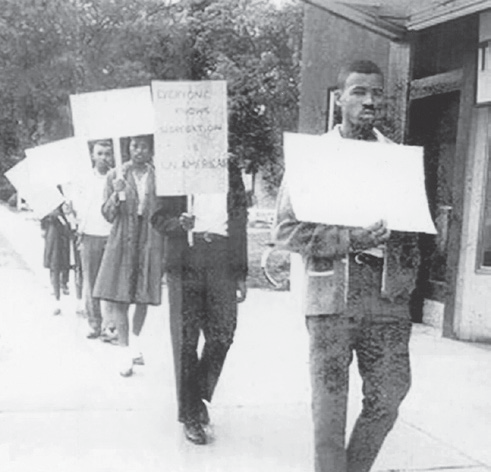

A protest against racial segregation at the Levon Theater, Enfield, N.C., in 1963. From The Nine O’Clock Whistle

Or the night that the town’s black citizens first refused to vacate Enfield’s downtown streets after the “Nine O’ Clock Whistle” rang?

Or the time, that same night, when white authorities turned the town’s fire hoses on black protestors, pounding children and their mothers and fathers against sidewalks and storefronts?

That last scene will of course bring back memories of the far more famous moment, just a couple months earlier, when Bull Connor turned the fire hoses on black protestors in Birmingham, Alabama. The most significant difference was that, in Enfield, as in so many small towns in the South, no national television cameras captured the scene in a way that would sear America’s soul.

Enfield citizens at the March on Washington, August 28, 1963. Photo courtesy, The Day They Marched, ed. Doris Saunders (1963)

I suspect that that every reader will find their own parts of The Nine O’ Clock Whistle that move them especially deeply. As for myself, I found that even some of the book’s smallest moments and briefest asides caught me off guard.

One that I am remembering now, for example, is Cynthia Samuelson’s account of the day that she discovered a carload of armed white men following her home. She was only 17 years old at the time.

Like so many of the incidents recounted in The Nine O’ Clock Whistle, it is a tiny moment, but captures something profound about the civil rights movement in Enfield as a whole. I will not give the story away here, but suffice it to say that it speaks volumes about how Enfield’s African American community prepared its children for just such moments and how the older generation stood vigilant, always ready to protect its young.

Poster of a “Freedom Day” voter registration drive, Enfield, N.C., May 2, 1964. Courtesy, Willa Cofield

Samuelson tells the story matter-of-factly, and in only a few sentences, but I found it wondrous, and in a way quite beautiful.

The Nine O’ Clock Whistle is the kind of book that only comes around once in a very long while. The voices of these African American elders are tenderhearted, but they brook no foolishness. (Two of the authors are retired public school teachers, after all.) In their words, we see Enfield’s civil rights movement through the knowing eyes of the women they are today, but also through the eyes of the young women and girls that they were in the 1960s.

We learn of one town’s struggle for racial justice but, through that story, also come to meet some of the central figures in the civil rights movement throughout the American South. We walk side by side with civil rights demonstrators in Enfield’s streets, but Cofield, Samuelson, and Sexton also show us an African American community that had been laying the moral, spiritual, and intellectual groundwork for those protests for generations.

The book’s account of the role that Black teachers and historically African American schools played in Enfield’s civil rights movement is especially compelling.

In the pages of The Nine O’ Clock Whistle, teachers such as Cofield and Lillie Cousins Smith, who was Cynthia Samuelson’s mother, are revealed to be part of a long tradition of Black educational leaders who, despite being under constant surveillance, and never having the resources available to their white counterparts, proved to be—to quote Matthew— as wise as serpents and as gentle as doves in their defiance of white supremacy.

Here, as vividly as I have ever seen, these three women—scholars, teachers, elders— help us to see and appreciate the subversiveness of African American education in the Jim Crow South.

Their narrative compels us to look anew at those Black teachers and their schools as a wellspring of the African American freedom struggle in the American South. In so doing, they help us to see the past more clearly, but also give inspiration to all those who are struggling today to speak the truth in classrooms throughout, in James Baldwin’s words, these “yet-to-be United States.”

This is the foreword that I wrote for Willa Cofield, Cynthia Samuelson, and Mildred Sexton’s The Nine O’Clock Whistle: Stories of the Freedom Struggle for Civil Rights in Enfield, North Carolina.

Published this week by the University Press of Mississippi, the book is now available at your local independent bookstore, Amazon.com, and wherever books are sold.

To arrange a book signing or other event for The Nine O’Clock Whistle, you can contact the book’s publicity agent at The African American Experience | The9oclockwhistle.