Graham Academy, Marshallberg, N.C., 1903. From Raleigh News & Observer, 13 May 1903.

This is the 3rd and final part of “A Journey to Sleepy Creek.”

In Marshallberg, the News & Observer’s reporter found a local fisherman willing to take him the rest of the way to Graham Academy.

The reporter, C. J. Rivenbark, wrote:

“I was soon aboard the skiff Tamar, sailing up Sleepy Creek to Graham Academy. Walter Davis, a bright young fisherman, was captain, and the trip was a pleasant one and made in a jiffy.”

Walter Davis was 21 years old at that time. He and his wife, Addie Lewis, of the Promise Land, lived in Marshallberg. In the coming years, they would raise five children together there.

As Davis guided the Tamar up the creek, Rivenbark took in the scenery.

“The Academy . . . is located . . . amid a pine forest of rare beauty. It is reached both by boat and a sandy roadway, lined with stately pines. The woodland has an undergrowth of numerous specimens of bush and shrub and vine.

“Pink, violet and jasmine blossoms are an added first charm, and their perfume mingled with that of the pine, is exquisite.”

The school occupied a site that locals had once called “Eph’s Old Field.” It was a four-acre plot of land on the road between Marshallberg and Gloucester, the next fishing village to the west.

At the heart of the campus was Star of Bethlehem Church, a Methodist Episcopal house of worship that locals usually just called “Star Church.”

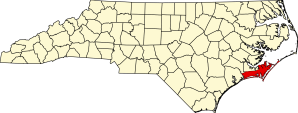

Marshallberg is located in Carteret County, N.C. Courtesy, Wikipedia

According a local Methodist church history published some 50 years ago, a group of northern missionaries and their friends– largely women– had established the church there in 1874.

They did so with the financial support of a missionary society up north, the Methodist Missionary Society of Boston.

Twelve years later, in 1888, Graham Academy grew out of Star Church. It was an unusual place for a prep school: the outskirts of a fishing village that was only reachable by boat and where the school’s assets included a four-acre oyster lease for helping to feed the students.

A group of Graham Academy’s students, May 1903. From the Raleigh News & Observer, 13 May 1903.

The school’s campus was plain, but adequate for the task at hand. There were, besides the chapel, only two other buildings. When Rivenbark arrived there, another was under construction.

One of the school’s buildings, Main Hall, housed a dining room, study rooms, and classrooms on its first floor. The female students’ dormitory was on its second floor. The school’s other building, Esther Pomeroy Hall, was a dormitory for male boarding students.

Esther Pomeroy was apparently one of the school’s benefactors. She was a wealthy older woman in Boston.

Of Graham Academy’s mission, Rivenbark wrote:

“Graham Academy aims primarily to give its students a thorough preparation for admission to the freshman class of the best colleges and universities of our country. It is not a college, but is intended to fill the gap between public school and the college, and also to give young men and women, who for any reason are unable to continue their work beyond the academy, a good sound education….”

The school’s mission was actually much broader. That was evident from the school’s enrollment. According to Rivenbark’s reporting, Graham Academy had 253 students during the 1902-03 school year, but less than a fifth of them were boarders– 20 young women and 15 young men.

Evidently, most of the school’s students were day students from Marshallberg and other parts of Down East. Judging from surviving photographs (such as the one above), they seem to have been all ages, including children who were quite young, and not just those bound for college.

Some of the children were the sons and daughters of Eastern North Carolina’s most prominent families, including those that had made their fortunes in the slave trade and plantation agriculture before the Civil War.

Others were the children of Methodist ministers and missionaries, for whom the school had a special scholarship fund.

But as best I can tell, most of Graham Academy’s students were from the remote fishing and farming villages Down East– and they were very often the children of mothers and fathers who had little, if any, schooling and who made their their livings working on the water.

All were white of course. Black and white children in North Carolina were not allowed to go to school together in 1903.

Graham Academy was especially well known for training some of the region’s finest teachers. Many of them taught in small one- or two-room schools on remote islands and in little fishing villages and country places, where they were, by all accounts, much needed breathes of fresh air.

A Down East woman named Sarah Elizabeth “Bettie” Gillikin was I think representative of many of those teachers. (I know of her because she is believed to be the namesake for the Down East community of Bettie, seven miles from Marshallberg, on the east side of North River.)

Born at North River in 1881, Bettie Gillikin earned her teachers certificate at Graham Academy as best I can tell sometime around 1897 or 1898.

I don’t know what classes she took at Graham Academy, but Rivenbark’s article makes it seem as if the school was bound to have exposed Bettie Gillikin to an extraordinary world of ideas and learning.

There in the headwaters of Sleepy Creek, according to Rivenbark, some students studied Homer’s Iliad , recited Latin and Greek, and read Milton. Others read Silas Marner, The Last of the Mohicans, and Longfellow’s poems. All got a grounding in English grammar and writing composition.

Some students– especially those preparing to be Methodist Episcopal ministers– focused more on Biblical studies, and yet others on natural philosophy and mathematics.

“A Corps of Consecrated Christian Teachers”

Christian teachings were central to Graham Academy’s mission. In his story in the News & Observer (13 May 1903), Rivenbark described the school’s headmaster, the Rev. C. M. Levister, and the six other members of the school’s faculty as “a corps of consecrated Christian teachers.”

He also observed that the Rev. Levister held daily chapel services at the school, and the boarding students ended their days with prayer just before lights out.

Rivenbark reported that a revival had been held earlier in the year where “more than 100 of the students were converted.”

On the other hand, he also noted that student attendance at chapel services was not mandatory.

Others students focused on music and music education. When Rivenbark arrived in Marshallberg, the school’s faculty had also just instituted a number of business classes, including typewriting and bookkeeping.

Aside from her classes, just being around students with so many interests, and coming from so many different places, had to have been a revelation for a young woman such as Bettie Gillikin.

And once she had that kind of schooling, she– and many other Graham Academy graduates– went on to share it with children in many of the most far-flung and remote corners of the North Carolina coast.

Graham Academy’s faculty, May 1903. The Rev. C. M. Levister, the school’s headmaster, is sitting on the far right in the front row. From Raleigh News & Observer, 13 May 1903.

After earning her teacher certificate at Graham Academy, Bettie Gillikin went on to teach in small, rural communities in other parts of Carteret County. One was Otway, not far from Marshallberg.

The other two were fishing villages located further away, on the long, narrow barrier islands called Shackleford Banks and Bogue Banks.

She taught first in Diamond City, a village on Shackleford Banks. She may even have been there when the hurricane of 1899 devastated the village and led the community’s people to abandon the island.

After teaching at Diamond City, she took a position at a one- or two-room school in Otway. She married a boatbuilder and fisherman named Macajah “M. C.” Adams there in 1910. After their marriage, the couple moved to Salter Path, on Bogue Banks, 20 miles to the west.

Bettie Gillikin Adams taught at Salter Path for seven or eight years, while she and her husband started their family. (They would have six children, though the first, Caldonia, named after her mother, died in childbirth.)

Sarah Elizabeth “Bettie” Gillikin Adams at her home in the Promise Land, Morehead City, N.C., circa 1970. This image comes from a lovely video posted on YouTube by the Promise Land Society back in 2014.

Teaching at Salter Path would not have been for just anybody, but for Ms. Adams, as she was known by then, the little settlement was not so much different than where she had grown up. At that time, Salter Path still had no roads, no electricity or indoor plumbing, and only about 80 residents, all of whom made their livings off the sea one way or the other.

In those days, according to one reminiscence, half of Salter Path’s children never graced the schoolhouse’s door. By the age of 10 or 11, most were helping their families make a living.

In such places– and there were many of them on the North Carolina coast in 1903– the arrival of a teacher such as Bettie Gillikin Adams was often an extraordinary moment in the lives of the children, and sometimes a turning point in the history of the community as a whole.

When I was younger and visited with old timers from Salter Path– and other such places– they often talked about the simple joys they had known in their childhoods, and also about a closeness to, and knowledge of, nature and the sea that few of us could imagine today.

But they also talked about growing up in a world that was hard-edged, unforgiving, and intolerant. So many people did without, beauty was often hard to find, and a better life impossible to imagine. For many children, and especially girls, the whole world seemed to be trying to beat them down.

But then a teacher– the right kind of teacher– would come and suddenly things would begin to change.

My mother did not grow up Down East, but she was raised in a small farming community 20 miles from Marshallberg. She often told me about her teachers and how much they had meant to her and her classmates.

My mother’s teachers, she remembered, were formidable women of great learning and unswerving moral rectitude. Several had been local suffragist leaders, and they were full of progressive ideas about women’s rights and possibilities.

Above all, they stirred my mother’s soul with poetry, art and music. One English teacher, in particular, read Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain and other modern literature to my mother’s class every day after lunch.

Other teachers had my mother and her classmates memorize long passages of Shakespeare that– and this I know– my mother and the hard-nosed sons of oystermen and one-mule farmers alike would treasure and remember to the end of their days.

My mother always made it seem as if her teachers had looked at life’s hardness, and decided that above all they would arm the children with poetry and stories, new and old– stuff that they would remember when they were lonely or needed consolation, or were lovesick, or had grown blind to the world’s beauty, or were feeling strangers to all that was delicate and tender.

(And yes, they taught their students to read and write and do arithmetic, too.)

I have to confess that, even here at the end of this three-part story I’ve been telling, I am still kind of working out in my mind why I wanted to write so much about C. J. Rivenbark’s journey to Graham Academy.

To some degree, I know that I was just excited to find a written account of Down East life in 1903– they are few and far between.

But more than that, I think that I was inspired to tell this tale by the thought of all those now long-gone teachers who came out of Graham Academy back in those days when you still had to take a boat Down East.

As I reflect on it now, I find myself thinking about that school and those teachers, and all those children, and all the little one- and two-room schoolhouses where Graham Academy’s graduates then went off to teach, and the lives they touched, and I just did not want them to be forgotten.

I know it sounds crazy, but I think I just wanted us to remember that, once upon a time, people thought learning was a good thing, and teachers were revered, their knowledge treasured, and schools were not treated like the enemy the way they are now, and that it was once considered a noble and honorable thing to bring light and tenderness and love into the world.

The Star Church/Graham Academy Cemetery today. The last burial was in 1916. Photo courtesy, rpkelly

David, the joy of learning is alive in you. Thank you for this article, the series, and your blog.

LikeLike

Lovely to hear from you, Matthew– and thank you for your kind words. Also great to see you in Raleigh the other day.

LikeLike

Love this story. Re Salter Path, we had a friend, Anna Salter, who was from Salter Path. Wonder if her father, a doctor, went a one room school. Also loved your story about the teacher in Hallsboro.

LikeLike

Thanks so much Patricia! We still have a lot of Salters in our neck of the woods too! Good folks.

LikeLike

Thank you, David for this essay. The last paragraph moved me to tears.

LikeLike

Thank you, Brenda. I know…

LikeLike

As always, an uplifting and insightful.

LikeLike

Many thanks!

LikeLike

David, good morning! I’ve been enjoying your historical subjects are North Carolina, One of the most interesting ones being the cannery industry. I’d like to ask you, if you come up

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing such wonderful stories that we would otherwise never know.

LikeLike

Thanks for your note– rough day today and it meant a lot to me!

LikeLike

My mother, Bernice Davis Dixon, was in the first graduating class from Smyrna High School. (I was in the last class.) She went on to get her B certificate teaching license from E.C.T.C. in 1928 and then taught at Salter Path school (one room, grades 1 through 8) until 1938. There she met my father Sterling Dixon. In 1938, they moved to Davis Shore where my mother had been born and raised. And yes, she had to ride the mail boat to go back to Davis for visits while teaching at Salter Path.

I have a photograph on my wall of my mother standing in front of the Salter Path School at the time she was a teacher. Some years ago, I was going through a filing cabinet at the Carteret County Historical Museum and found some public school registers which teachers were required to keep listing their students, parents, attendance, etc. I found mama’s from Salter Path from before she was married (Bernice Davis), and low and behold, she had my Aunt Bessie Dixon and my Uncle Stephen Dixon in her class. Never knew that. Later I was attending the Core Sound Museum’s homecoming for the Diamond City descendants and introduced myself to Mr. Henry Frost from Salter Path who had spoken at the event. When I said that I was sure he remembered my father, he replied, “Know your father! Your mama was the best teacher I ever had. Everything I know I learned from her.” I just loved that.

Finally, I appreciate your kind words about the teachers of that era. I took had some great ones at Smyrna: Miss Mary Whitehurst (3rd and 5th), Miss Josie Pigott (8th), and Mrs. Anne Salter (junior English). They too believed in assigning memory work. Some of those poems and other writings I carry with me today.

LikeLike

What a treat to hear from you, Ms. Dixon! I was so exited to hear your stories about your mother and Salter Path! And Mr. Frost’s exclamation, “Your mama was the best teacher I ever had!”– I know that meant the world to you! My mother, Yvonne Bell, was I guess a little younger than your mom– she was Beaufort High School, class of ’44. But how I used to enjoy going to her class reunions with her, even 60 years after her graduation– I could have listened to their stories many an hour! (And sometimes did!) They could not have put their teachers on a higher pedestal! Thank you for writing!

LikeLike

Dear Mr. Cecelski, As a former teacher this almost brought me to tears. Thank you so much. I have enjoyed all of your writings but this one was special. Sincerely, Jack Sandberg

LikeLike

Thank you for your kind words, Jack. Hang in there.

LikeLike

I loved the article “Reading Shakespeare Down East”. And in particular, the last line. It was not too long ago that a reverence for education was central to virtually all families. Thank you for the lovely reminder! Keep up the great work that you do.

LikeLike

Many thanks, John– and good to hear from you.

LikeLike