My cousin Edsel Bell’s oyster knife, his last gift to me, Harlowe, N.C. Photo by David Cecelski

This was my keynote address at the North Carolina Coastal Federation’s “Coastal Summit” in Raleigh, N.C., April 8, 2025.

This may not be the kind of keynote address to which you are accustomed. I am a historian after all, a storyteller at heart, and you have to expect that I am going to tell a few stories.

So I will warn you, I am going to show you a few family photographs, just to let you know a little about the part of North Carolina’s coast where I grew up. I am going to do a little Show and Tell as well, and I am also going to introduce you to a few friends of mine from the coast.

Once you have met my friends and know a little about my home, I am going to talk about our coastal history, and how we got here, and what we might learn from our past that might help guide us today.

But first, as I said, a few family pictures. These are from my grandmother’s farm in Carteret County, where I spent much of my childhood and where my wife and I still spend much of our time.

This is me and our pony Bay at my family’s homeplace in Harlowe, N.C., probably 1963 or ’64. Bay was one of several Banks ponies that my mother’s family had over the years.

This is my brother Richard and me at my grandmother’s farm in Harlowe, N.C., 1963 or ’04ish. As you can tell, we were pretty much running the place by that time.

My mother’s family has deep roots on that part of the North Carolina coast. When I am there, I sleep in the bedroom where my mother was born, and her father before her, and on and on back in time.

But when I was young, old timers still called our house “the new house,” even though it was built before the Civil War, because there is a much older house a half-mile down the road on my cousin Henry’s farm that is where my grandfather’s family lived before our house was built.

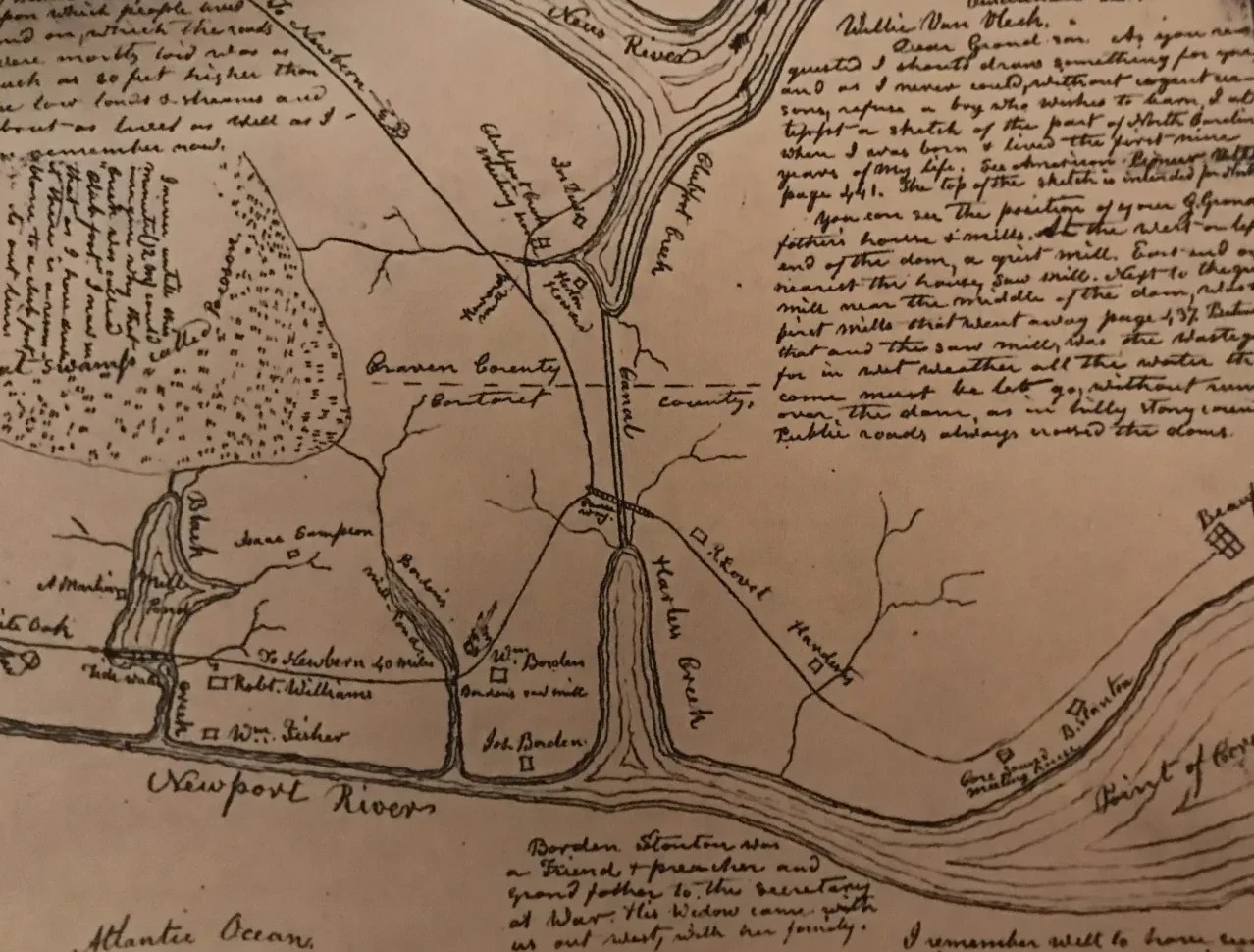

I also thought that you might be interested in seeing this old hand-drawn map. Created by one of the Quakers who settled our part of the North Carolina coast in the 1700s, the map is more than a little rough and painfully out of scale, but you can still make out our local landmarks.

The long north-south line in the central part of the map is the Harlowe Canal, which was dug by enslaved laborers in the early 1800s. My family’s homeplace sits on the west bank of the canal roughly midway between its outlet on Clubfoot Creek and its outlet on Harlowe Creek.

The town of Beaufort, barely a village at that time, is on the lower righthand part of the map.

Map of the Quaker settlements on the north side of the Newport River ca. 1800, in John Shoebridge Williams, The Williams History: Tracing the Descendants in America of Robert Williams, of Ruthin, North Wales, who Settled in Carteret County, North Carolina, in 1763. (Drawn ca. 1850-60.) For more on the map, see my story, “The Quaker Map: From Harlowe to Mill Creek.”

Now for my little Show and Tell. I know many of you are active in protecting and building our state’s oyster industry and I thought that you might like to see my cousin Edsel’s oyster knife.

This knife was hand-forged more than a century ago. It originally belonged to Edsel’s father, my great-uncle Armistead. He was an oysterman by trade, and he carried this oyster knife on his boat and used it to shuck the oysters that were his only lunch most days on the water.

Back then, oysters were a staff of life, and often, according to Edsel, the difference between going hungry or not.

As long as I knew Edsel, he carried his father’s oyster knife in his pocket six months a year, just in case he came upon an oyster.

That’s the kind of place where I grew up.

When Edsel died a few years ago, he left me the oyster knife. There is nothing I could have wanted more.

Finally, the photographs that I will show you now are portraits of coastal people whose life stories I featured in my historical writing over the years. Nearly all are gone now, but many of them were people whose friendship and lessons in life came to mean a great deal to me.

Alice Eley Jones and her father’s herring net, Murfreesboro, N.C. From my story, “Alice Eley Jones: Herring Fish,” Raleigh News & Observer, 12 March 2006. Photo by Chris Seward

I wish that I had time to share their stories with you today, but I think that will have to wait for another time.

For now, I just wanted them here with us. I thought that they might spur me, as I speak with you, to draw as deeply as I can from the lessons about the North Carolina coast that they taught me.

-2-

So now, a little historical perspective.

When my mother was born, a New Bedford, Massachusetts, company was still trapping bottlenose dolphins by the thousands and slaughtering them on the beach at Hatteras Island.

At Hatteras, the villagers used to shut their windows at night so they would not have to hear the cries of the dolphins on the beach. (Often, when the day’s last haul finished after dark, they left the dolphins alive on the beach until they butchered them the next morning.)

When I was young and the dolphin hunters were old men, they would tell me that they still had nightmares about what they had had to do on those beaches.

David Harrell, Rockyhock, N.C. From my story, “David Harrell: A Rockyhock Christmas,” Raleigh News & Observer, 12 Dec. 1999. Photo by Chris Seward

When my grandfather was a young man, New York millinery firms—the makers of ladies’ hats—were still paying hunters at Cape Lookout to surround nesting colonies of sea birds and marsh birds.

The hunters would wait until a colony’s eggs had begun to hatch, because that was when the birds were least like to flee.

Then they would start shooting. In a single day, they would sometimes kill 10, 15, 20, 25,000 birds.

Great, vast colonies of royal terns. piping plovers, sanderlings, herons of all kinds, egrets and many other nesting birds were driven to the edge of extinction on our shores.

A century ago, the swans and snow geese did not come to Lake Mattamuskeet.

A century ago, our sea turtles were being shipped in tin cans to four-star restaurants in New York City, instead of drawing pilgrims from the four corners of the globe to our shores.

A century ago—well, closer to 85 years ago— a pulp mill, without breaking any laws, began dumping untreated sulphur dioxide into the Roanoke River at a site four miles upriver of Plymouth.

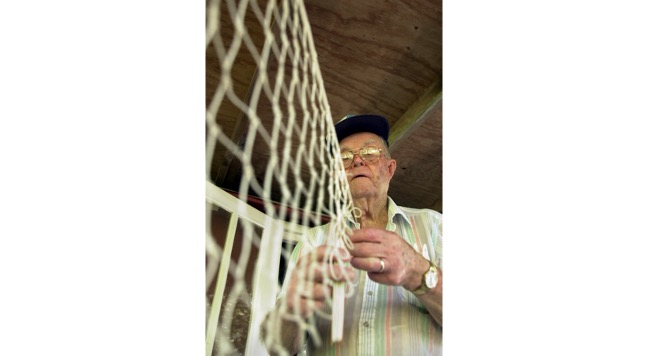

Wesley Goodwin, Sea Level, N.C. From my story, “Wesley Goodwin: Knitting and Hanging Net,” Raleigh News & Observer, 12 Aug. 2001. Photo by Chris Seward

By the start of the Second World War, that mill’s wastes had destroyed one of America’s largest and oldest river herring fisheries, dating back at that site almost two centuries.

A century ago, lumber companies clearcut and drained one of North America’s most magnificent old-growth swamp forests, a vast and incredibly diverse wetlands north and west of the Pungo River.

Once covering more than a hundred thousand acres, those ancient forests of Atlantic white cedar and cypress simply disappeared. And the hundreds of miles of canals built to drain the wetlands channeled a sea of freshwater into our estuaries, dooming the oyster beds of the upper Pamlico.

If a single acre of that great wetlands has survived, I have not yet found it.

I am afraid I could go on and on— and on. But I am sure that you get the idea. Especially between the Civil War and the Second World War, our coast was the site of a kind of brutal exploitation and ruin that I can only compare to what I have read about the Amazon rain forest today.

I am here to tell you that everything we love about the North Carolina coast today has come about because we recognized that we could not keep going on that way.

Gretchen Brinson, Morehead City, N.C. From my story, “Gretchen Brinson: A Born Nurse,” Raleigh News & Observer, 14 June 1998. Photo by Chris Seward

We learned the hard way that the strength of our coastal communities, the strength of our coastal families, and the strength of our coastal economy are as entwined as anything can be with the health of our coastal waters, our wetlands, our fields and forests.

We learned, too, that our coastal heritage is also bound to those waters: the survival of our fishing communities, our boatbuilding heritage, our traditions of living off the land and out of the water, our oyster roasts and shrimp boils, our annual pilgrimages to the shore to restore our souls, and so much else.

All those things that matter so much to us depend on our taking care of our coastal waters and wetlands.

Though it was not easy, we learned that we have to work together if we want to keep our coast the kind of place that our children and grandchildren will hold as tightly in their hearts as we hold it in our hearts.

-3-

I know, and I know you know, that we have much left to do. I do not mean to say that history teaches us that, “Things got bad, much was lost, we saw how bad things got, and we fixed everything and now everything is OK.”

I certainly do not mean to say that. I also do not mean to say that, well, we passed some environmental laws. We required some public hearings. We set aside a few national seashores and wildlife refuges, a state park or two, and a bit of national forest, and that is all we needed.

You know that is not true, and that is not what I am saying. But I do hope that you, all of you who cared enough to be here today, will not forget that you are continuing a proud tradition of people who have worked heart and soul to protect the North Carolina coast and its people.

I am thinking of individuals such as Rachel Carson, the author of Silent Spring, The Sea Around Us, and other groundbreaking works on our coastal world. Widely considered the mother of the environmental movement, Carson did much of her early scientific work on our coast.

I am also thinking of local people such as our old friend Lena Ritter of Stump Sound, Neuse River keeper Rick Dove, environmental justice activists like Gary Grant and Donna Chavis, and the Coastal Federation’s founder, Todd Miller, among many, many others.

Poet, songwriter and fisherman’s daughter Virginia “Ginny” Richardson, Sneads Ferry, N.C. From my photoessay, “Remembering Sneads Ferry in the 1930s.” Photo by David Cecelski

Speaking as a historian, I want to remind you that people like them– and people like you– have made progress on all kinds of environmental issues that would have been impossible to imagine a century ago.

Of course, at the same time, we also cannot forget that, in a lot of ways, we have just got started.

And I know—when we see what is going on in the country right now— that things look bleak for so much of what draws us and people from around the world to our shores.

I know too that much of the extraordinary work that you are doing to make our coast a better place may be in danger now.

Menhaden fisherman Eugene Gore, Southport, N.C. From my story, “Capt. Eugene W. Gore, The Smell of Money,” Raleigh News & Observer, 9 June 2002. Photo by Chris Seward

And I know that there are people in high office now who act is if . . ., well, act as if they’ve never walked down the Kure Beach Fishing Pier on a Friday night in the autumn.

They act as if they’ve never seen the excitement of a bluefish run at a pier like that, or the joy in the children’s faces, and how nobody on the pier is a stranger, and how much it means to all our state’s citizens to be close to the sea.

They act, too, as if they have never walked the shores of Cape Lookout, when the sea is phosphorescent, and the dolphins are playing out in the waves, and the fish are biting.

And they act as if they’ve never strolled along the edge of Currituck Sound and felt the beauty of the marshes stir their soul. Or stood out in a field like we do back home and slowly roast oysters over hot coals, while the old people tell stories and little children dance around the fire.

Clarence Alston, Navassa, N.C. From my story, “Clarence Alston: It was 1919,” Raleigh News & Observer, 11 Sept. 2005. Photo by Chris Seward

The shackling of the EPA alone foreshadows a breathtaking descent back into the dark days of our coastal past—when our estuaries, our beaches, our fisheries, and the sources of our drinking water were a free-for-all, open to plunder, pillaging and poisoning.

I wish I had more words of comfort for you, but there is no point to sugar coating the challenges we face.

We all know the road ahead will not be easy. And we all know that the importance of the North Carolina Coastal Federation and its partners—in business, government, academia, and at the coastal grassroots– will never, ever be greater than it is at this moment in our history.

Public school teacher Dorcas Carter, New Bern, N.C. Ms. Carter’s grandmother had been a fisher-woman on Portsmouth Island. From my story, “Dorcas E. Carter: The Great Fire of ’22,” Raleigh News & Observer, 14 Jan. 2001. Photo by Chris Seward

Let me leave you with a story.

I believe that I was invited to speak with you today primarily because of my historical work on the North Carolina coast. However, I also happen to have a long history with the North Carolina Coastal Federation.

In fact, according to the Coastal Federation’s founder, Todd Miller, I was the organization’s first volunteer. That was something I did not know until recently. But a couple years ago, I had the great honor of receiving one of the Federation’s Pelican Awards, along with my brother Richard.

When Todd presented our awards, he mentioned that I had been the Federation’s first volunteer. I have to confess that I had never really thought about it, but I guess it is true: more than 40 years ago, when we were both green as gall, Todd somehow talked me into moving to Swan Quarter to spread the word about a massive strip-mining project.

At that time, a large, extremely well-connected group of wealthy investors was planning to strip mine a vast swath of the North Carolina coast to extract the peat and use it as a fuel.

The project would have devastated hundreds of thousands of acres of coastal wetlands across Dare, Hyde, Tyrrell, Beaufort, and Washington counties.

Yet when I got to Swan Quarter, I rarely met anyone who even knew what was happening. The strip-mining project had been presented to them as something that was a done deal and need not concern them.

On the few occasions when I did encounter a local individual who had some knowledge of the strip-mining project, and who realized that it would leave their home a wasteland and devastate the region’s oyster beds and fishing grounds, they had little hope of doing anything about it.

Their past experience, they told me, had led them to conclude that nobody in Raleigh or Washington, DC cared what they had to say. They felt as if they had no one on their side, and they saw no point in raising their voices when nobody was going to listen anyway.

I lived there on the shores of Lake Mattamuskeet most of that year.

At the time, the Coastal Federation was brand new and had very little money, so local families took care of me and gave me a place to stay. Commercial fishing families fed me, carried me into the cranberry bogs at Christmas, and made sure I never missed a church supper.

Above all, they taught me a great deal about what it means to be bound so deeply to our coastal waters and wetlands.

Swamp rat Ray Wells, near Wallace, N.C. From my story, “Ray Wells: There’s a Man for You,” Raleigh News & Observer, 8 Nov. 1998. Photo by Chris Seward

My job—the job Todd gave me because he did not have anyone else—was only a very small part of the puzzle, and it was very simple: I was just supposed to let people know what was happening and help their voices be heard.

So I hung out at the docks. Visited fish houses. Talked to people in their homes if they invited me to do so. Went to a lot of church services. Talked with people everywhere from pool halls to duck blinds.

Another young man, Greg Zeph, a gem of a fellow, was also working with me. And before long, local people—a woman crabber in Pamlico Beach, a pair of fishermen in Stumpy Point, a farmer in Rose Bay, and many others— were spreading the word much better than we ever could.

Commercial fisherman Hildred O. Golden, Stumpy Point, N.C. Mr. Golden was one of the fishermen who worked with the N.C. Coastal Federation to challenge the peat-mining project back in the early 1980s. From my story, “H.O. Golden: A Man’s Work,” Raleigh News & Observer, 12 June 2005. Photo by Chris Seward

At that moment, I would not have bet five bucks on the chance of our success. Everything—money, power, time—was against us.

But little by little, people of every background, every political party, and in every little village began to speak up.

Hope flickered. People began to come together. The more they came together, the more they believed that they could make a difference. And in the end—it seems like a miracle when I think about it now— we—the people of the North Carolina coast— prevailed.

Hattie Brown, Goshen (near Pollocksville), N.C. From my story, “Hattie Brown: A Freedom Story,” Raleigh News & Observer, 9 Aug. 1998. Photo by Chris Seward

Over that winter, I got my first good look at Todd Miller and this new group called the North Carolina Coastal Federation. The peat-mining campaign was the Federation’s first big endeavor, and at that time Todd was not even able to pay himself a full-time salary.

Yet from the very first, I could already see the ingredients that would make the Federation so important to us all in the coming years.

I still remember how deeply impressed I was by the way the way Todd worked so closely and respectfully with the Federation’s just-emerging partners—other environmental groups, elected officials, local fishermen and women, the scientific community, and many others.

More than anything, I was struck at how Todd just thought that everybody deserved to have their voice heard.

Commercial fishermen and recreational fishermen, farmers and small businesspeople, Democrats and Republicans, corporate leaders, elected officials, scientists, marine educators, local, state, and federal officials— he believed that they all had a vital role to play in caring for the North Carolina coast.

I was very young then—I was nowhere close to being a historian yet— but that experience taught me that, even when things look bleak, and even when everything seems against us, if we do not give up hope, if we hold onto one another, if we look past our differences to what we hold in common, good things will happen—and sometimes even a miracle or two.

Maude Ballance, Ocracoke, N.C. From my story, “Maude Ballance: Ocracoke Cooking,” Raleigh News & Observer, 11 July 2004. Photo by Chris Seward

I know that I am a terribly old-fashioned person. (I mean, I still salt and dry mullet roe the way the old people back home did when I was a child!)

I know I am out of step with much of modern times. I still believe, for example, in the Golden Rule, that we should treat other people the way that we would want them to treat us.

I still believe what I was taught in Sunday school, that we are called to be good stewards of God’s creation and good caretakers of our lands and waters and the creatures thereof.

I still believe, and I will always believe, what I learned growing up on the North Carolina coast, that a neighbor is a neighbor is a neighbor, and that we are all in this together.

And I believe with all my heart that there are some things worth fighting for, and I believe that the North Carolina coast is one of them.

A pretty batch of mullet roe. Photo by David Cecelski

Love your work!

LikeLike

Thank you so much!

LikeLike

Good morning, David,

I am volunteering this morning at Stagville. In the stillness, before people start arriving for self-guided tours and the guided tour at 1pm, I am reading “Our Coastal Heritage: Past, Present, and Future.”

Thank you for writing, delivering, and sharing this beautiful, powerful keynote address. It took awhile to read because I often had to pause and wipe tears from my blurry eyes, especially when I got to the last part of your talk—about the volunteer work you did 40 years ago on the coast, working with others to stop the peat mining from proceeding; mining that would have devastated the region.

From start to finish, your keynote address is the kind of heartfelt and historically-rooted testimony we need right not. In this exceedingly bleak time. Yours is a testimony to how we can work together–to learn from history, minimize injustice, care for the earth, cherish the gifts of this world, reignite each other’s passion for justice, recover hope day in the doing, and “turn things toward the morning,”

Thank you for your volunteer work 40 years ago. Thank you for your work as a historian. Thank you for your ongoing historical work and story telling in the newsletter pieces you send us. And, again, thank you for this keynote address.

Gratefully,

Melanie

Melanie S. Morrison Website: http://www.melaniemorrison.net

Author of Murder on Shades Mountain: The Legal Lynching of Willie Peterson and the Struggle for Justice in Jim Crow Birmingham (Duke University Press)

Author of Becoming Trustworthy White Allies (Will be published by Duke University Press in Fall 2025)

Surrender to none the fire of your soul. ~ Pauli Murray

>

LikeLike

Dear Melodie, I cannot tell you how much your note meant to me– thank you from the bottom of my heart. And it’s wonderful to hear from you out at Stagville! It’s always such a treat to see you out there working with Vera! I’ll keep at it if you will! (And I know you will!) warmest regards, David

LikeLike

Mr. Cecelski:

I have been a avid reader of your thoughtful stories of our beloved NC coastal area. Your recent speech/story that you have given to the NCWF and republished here was the most moving piece that I have read to some time. As I reach my 76th year on this planet we call Earth, I too was like most of your first encounters a Mattamausket in that we cannot fight the powers of our governing bodies. But the NCWF, Todd Miller, and your efforts proved me wrong.

For the last 10 years, I been a member of the NCWF to supported their mission. It is a noble cause and must be supported by all North Carolinans’ if we expect to have the coastal environment for our children that we have taken for granted.

Thank you your dedication to history of our coastal forefathers and the survival of our precious envoronment and helping us keep the spirit alive for our ancestors.

Keep the great stories coming,

Charles Godwin

LikeLike

Thank you, a thousand times, for your note, Mr. Godwin. Words like that can keep a guy going for a long time– so again, thank you. And best wishes in all. David

LikeLike

Magnificent piece. Thank you for your inspiring words.

LikeLike

Thank you, John (as always)

LikeLike