View of bald cypress trees along the shore of Lake Phelps, Washington County, N.C. Photo courtesy, Pettigrew State Park

“I am not writing of what I have heard, but of what I have seen, and of what I defy the world to prove false.”

“My father taught me to hate slavery; but forgot to teach me how to conceal my hatred.”

— John Swanson Jacobs

The recently discovered slave narrative by John Swanson Jacobs is breathtaking. I do not think I can describe how deeply it touched me, or how profoundly it changed the way that I see some of the places on the North Carolina coast that I have known all my life.

Consider Lake Phelps, a broad, shallow lake on the border of Washington and Tyrrell counties, deep in the pocosin swamplands near the headwaters of the Scuppernong River.

I have visited the lake many times in my life. But I will never see it the same. After reading Jacobs’ narrative, I am not even sure I will ever be able to call it “Lake Phelps” again.

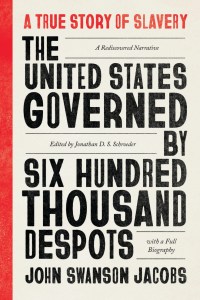

Jacobs’ account was first published in a newspaper in Sydney, Australia, in April 1855. He called it The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots: A True Story of Slavery.

He was born into slavery in Edenton, N.C., in 1815. He escaped to New York in 1839. After gaining his freedom, he went to sea. He served on a whaling ship in the Pacific for several years, then returned to New England and was active in the anti-slavery movement.

At that time, he also reunited with his sister, Harriet Jacobs. A noted abolitionist and writer, she is the author of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which is now recognized as a classic of Early American literature.

Gilbert Studio portrait of Harriet Jacobs, 1894. Original in the Harriet Jacobs Family Papers, National Archives, Washington, DC

Harriet Jacobs had escaped from Edenton in 1842, three years after her brother’s flight to the north.

To Australia and Back

Soon after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, John Jacobs left New England again. He first joined the California Gold Rush, then crossed the Pacific in search of gold in Australia.

One of the largest gold rushes in world history had begun in New South Wales in 1851. Jacobs was one of hundreds of thousands who traveled to Australia from around the world to work in the mines.

According to the National Museum of Australia: “Between 1851 and 1871 the Australian population quadrupled from 430,000 people to 1.7 million as migrants from across the world arrived in search of gold.”

After four or five years of mining, having apparently made enough to live, but not much more, Jacobs prepared to go back to sea.

Gold Washing. Fitzroy Bar, Ophir Diggings, 1851, George Angas. National Museum of Australia. More than 16,000 Americans were among the “diggers” that joined the Australian Gold Rush.

Before he left Australia though, he penned The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots.

Sydney’s leading daily, The Empire, published Despots in two installments in that spring of 1855.

Though Despots must have reached many readers in Sydney, it was soon forgotten there and it remained unknown here in the United States until just a few years ago, when a literary scholar named Jonathan D. S. Schroeder found the narrative in old copies of The Empire.

In the introduction to a scholarly edition of Despots that was published last year, Schroeder explains that he discovered the narrative while researching Harriet Jacobs’ son Joseph.

Just last year, the University of Chicago Press made The United States Governed by Six Hundred Thousand Despots: A True Story of Slavery available here in the United States for the first time. Edited by Jonathan D. S. Schroeder, the book includes the narrative’s full text, along with annotations.

In addition, Schroeder has included a lengthy biographical essay on John Jacobs in the book, as well as two appendices. The first appendix features John Jacobs’ letters to other anti-slavery activists in New England, after his escape from Edenton.

The second appendix features a group of letters, articles, and a diary entry that refer to John Jacobs in the period from 1845 to 1862.

Following his uncle’s lead, Joseph Jacobs had left the U.S. and gone to work in Australia’s mines. That apparently led Schroeder to examine some trove or another of Australia’s old newspapers, including the two issues of The Empire that featured Despots.

The Shores of Lake Phelps

The chapter of Despots that mentions Lake Phelps begins with John Jacob’s scathing appraisal of one of Edenton’s leading white citizens, a wealthy planter, merchant, and banker named Josiah Collins II.

To appreciate the passage fully, I think you need only know that Collins, in addition to his financial interests in Edenton, owned a large plantation called the “Lake Farm” at Lake Phelps, a broad, 16,000-acre lake down in a remote swamp forest on the other side of the Albemarle Sound.

Fundamentally, the Lake Farm—also known as Somerset Place— was a massive slave labor camp. Following in his father’s footsteps, Josiah Collins II confined hundreds of Black men, women, and children there.

All those who have read Dorothy Redford’s glorious memoir, Somerset Homecoming: Recovering a Lost Heritage, will remember that Somerset Place– the Lake Farm– had been an especially notorious slave labor camp since enslaved Africans first carved it out of the swamplands in the 1780s.

A descendent of Africans enslaved at Lake Phelps, Redford was a pioneering public historian and a longtime executive director of the Somerset Place State Historic Site.

The plantation’s fields covered several thousand acres along the shores of Lake Phelps. However, that was only a small part of Josiah Collins II’s property. Between Lake Phelps and the headwaters of the Pungo River, he owned more than 100,000 acres of land.

The Black people that he held in slavery worked in his fields, but also in those swamp forests, cutting lumber and shingles. They dug canals and ditches, and they worked at fishing beaches.

Among his peers, Josiah Collins II was considered one of the state’s most respected business, civic, and church leaders. I suppose it is not surprising that John Jacobs saw him in a different light.

“A Congregation of Tyrants”

John Jacobs discusses Josiah Collins II and Lake Phelps in the fourth chapter of Despots. It is one of many places in Despots that you can tell that he was a bold and militant spirit.

His anger at slavery’s inhumanity almost explodes off the page. You can tell too that he was not looking for sympathy: he was chronicling inhumanity and the sins of a country where he held all those who were tolerant of slavery in the United States to be complicit in that inhumanity.

That is the source of the “600,000 Despots” in his title. He is referring to all white citizens who stood silent in the face of slavery.

Jacobs devotes that fourth chapter of Despots to chronicling some of the ways that he had seen Edenton’s slaveholders punish enslaved men, women, and children for their acts of defiance.

He tells, for instance, of the town’s whipping post, where he had witnessed enslaved men and women stripped naked in public and lashed until their “backs were cut to pieces.”

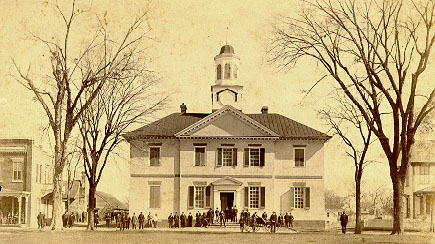

The whipping post was located behind the Chowan County Courthouse, a few steps from Josiah Collins II’s door.

Chowań County Courthouse, Edenton, N.C., in 1890. During John Jacobs’ youth, the courthouse was well known for its scenes of brutality and public humiliation. A whipping post, stocks, and a pillory could all be found on its grounds. Photo courtesy, N.C. Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Jacobs found other ways of disciplining slaves more savage yet. I think I will let you find some of them for yourself, if you are so inclined; I am not sure the descriptions of them are suitable for younger readers, and I think they might be hard for some adults to read as well.

I will say though that the worst of those punishments, the one that Jacobs called “the most cruel torture,” led him to bring Josiah Collins II into his account of slavery in Edenton.

“This was Mr. Collins’s favorite way punishing slaves,” Jacobs told his readers. He then went on to say:

“Mr. Collins was a member of the ———– Church, and to a stranger would seem to be a very kind-hearted, good man.”

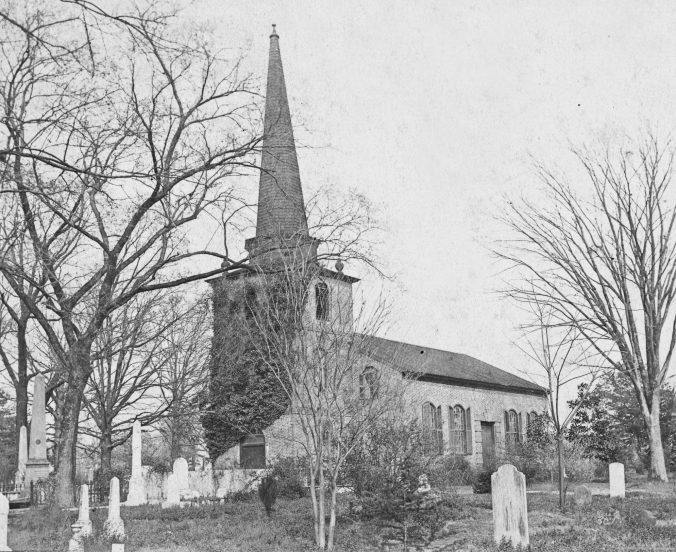

Josiah Collins II was a longtime vestryman and lay leader at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Edenton. In 1817, he was one of the 10 founders of the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina.

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Edenton, N.C., undated (from the church’s archive).

In his narrative, Jacobs indicates that those enslaved in Edenton referred to St. Paul’s as “The Brick Church.” Many of the town’s largest slaveholders worshiped there.

“It was known by this name to all the slaves, and the members were considered a congregation of tyrants.”

John Jacobs went on to use Josiah Collins II to illustrate how differently many of the town’s leading white citizens were viewed in Edenton’s mansions and in its slave quarters.

“Every slave that met him would pull off his hat and make a polite bow, which Mr. Collins would return,” he wrote.

“If he was a day or two from home, when he returned, his slaves that were about the house, would take his hand and inquire after his health.

“Is it love, that his own and other people’s slaves have for him? No, but fear. Mr. Collins always has at hand a cane, to teach politeness to such as have not learnt it.

“I have known him to flog others’ slaves for not taking their hats off to him, when he has been on the opposite side of the street; and on one occasion he met a slave with a quarter of mutton in each hand, and flogged him because he did not shift the two into one hand, until he could raise his hat….”

In Despots, Jacobs then relates a brief tale about a mother, her son, and two other children.

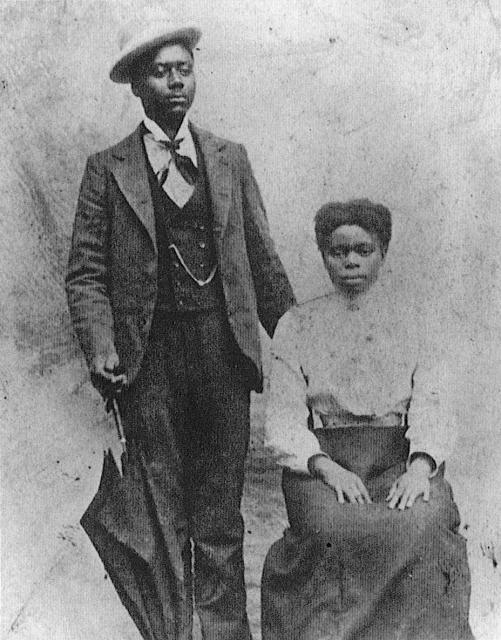

According to North Carolina State Historic Sites’ stellar #TrueInclusion website, August Ann “Gustanna” Collins was one of the survivors of the Collins family’s plantation at Lake Phelps. Born there circa 1846, she gained her freedom with the fall of the Confederacy in 1865. She and her husband James Cabarrus (seen with her here) eventually settled in Creswell, a small town a few miles from Lake Phelps. Photo courtesy, North Carolina State Historic Sites

This is where he finally mentions Lake Phelps.

“I was an eyewitness to more than one hundred blows each, being given to two lads belonging to Mr. Collins, and they were then sent to the Lake Farm, a place that will well bear the name I once heard a poor slave mother call it, who was taking leave of her son—

“`He is going,’ she said, `to the lake of hell.’”

There are some things you cannot un-know, just as there are some things you cannot undo.

All of which is to say: I have been visiting and studying historical events at Lake Phelps for a long time. And I have never forgotten the harrowing scenes of slavery recorded in Dorothy Redford’s Somerset Homecoming.

But all it took was the one second that I read that slave mother’s words—“the lake of hell”—and the lake’s name changed for me forever.

Wow!! What a story!!!!! Thank you!

Catherine Bishir

>

LikeLike

Thank you! I’m

LikeLike

All your stories are stunning, though I have been neglectful in expressing it, and my gratitude. I’m very familiar with that area, the lake, and Somerset . I cringed reading Lake of Hell, so now view it all through a far different lens. Its power is unshakable. It nudged me to now convey how much I appreciate your research and skilled presentation. Thank you so much.

LikeLike

Thank you for your kind note, Molly. And you’re welcome. I very much appreciate you taking the time to write- I know it’s a small thing but it means a lot to me, especially when someone seems so sincere. Again, thank you. David

LikeLike

David, thank you for sharing this. Just ordered the book.

LikeLike

David, thank you for sharing this. I just ordered the book.

LikeLike

Good one

LikeLike