High bush blueberries (Vaccinium corymbosum). Courtesy, Wikipedia

“The huckleberry is something to be wrestled from bramble and chigger by armies of pickers, young and old, white and black, and to be brought in indigo-stained buckets to general merchants to pay 10 cents a quart cash and in turn grade and package … [for] housewives in Boston and Providence….”

Raleigh News & Observer, 19 June 1938

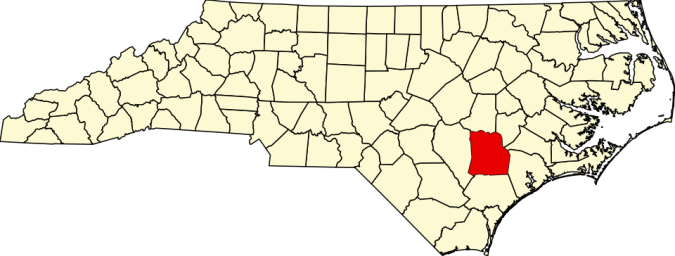

As I drove by the blueberry farms along the Black River the other day, I thought about the early, pioneering days of blueberry farming. That part of Pender and Sampson counties was home to some of the first commercial blueberry farms anywhere in North America back in the 1920s and ’30s– and today blueberries are one of the region’s most important farm crops.

But my mind also went further back in time.

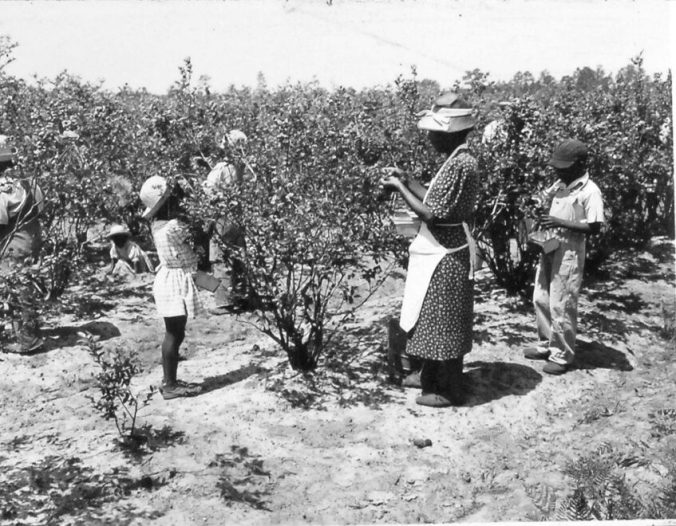

A woman and her children harvesting blueberries at a farm near Burgaw, N.C., June 1947. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Long before the first commercial variety of blueberry was developed, the wild blueberries of Sampson County, North Carolina, were famous all the way to New York City and Boston.

Every summer, legions of local people– black, white, and Native American– foraged the wild blueberries in the Carolina bays and creek bottoms that are found throughout that part of southeast North Carolina.

Local people called them “huckleberries.” Botanically speaking, they were actually a variety of blueberry. Large and very sweet, they inspired great crowds of people to venture into the “huckleberry woods” and ‘huckleberry ponds” every year in search of them.

In Sampson County, people harvested more than one variety of wild blueberry. However, only one variety, a large, sweet berry that came to be known as a “Sampson blue,” attained great commercial value along the East Coast in the late 19th century.

I am not clear exactly what variety of wild blueberry the so-called “big blues” or “Sampson blues” were. However, I suspect that they were either a blueberry whose Latin name is Vaccinium formosum or a blueberry whose Latin name is Vaccinium corymbosum.

Wild highbush blueberries can grow to a height of 15 feet and are known for their large, sweet berries that, in southeast N.C., are ripe in May and June. Photo courtesy, The Plant Native

Vaccinium formosum is also called the “swamp high bush blueberry,” while Vaccinium corymbosum is often called the “northern high bush blueberry”– it often reaches heights of 6 to 15 feet.

The leaves of these wild blueberry bushes make for an unforgettable sight in the fall. Photo courtesy, The Plant Native

Both of those varieties were abundant in the moist, slightly acidic, white sand and black organic soils that are common in the Carolina bays and pocosin bogs that are such a distinctive part of the landscape in much of southeast North Carolina.

The wild blueberry bushes are also an important food source for migratory birds, as well as a host plant for the spring azure caterpillars that turn into lovely butterflies like this. Photo courtesy, The Plant Native

The Sampson Blues

According to an excellent article by local historian A. J. Bullard that appeared in the Sampson County Historical Society’s newsletter, the wild blueberries found in those low-lying areas were already a cash crop for people in Sampson County by the late 1700s.

Wild blueberries flourished no place more than in southeast N.C.’s “Carolina bays,” which are elliptical or circular shaped depressions in the earth of uncertain geologic origin. Roughly 80% of the known Carolina bays are located in N.C.’s coastal plain, the greatest number of them in Bladen and Columbus counties. Some are lakes; others are pocosin bogs; some have dried up completely, but their outline can still be seen from the air. This is Warwick Mill Bay, a Carolina bay in Robeson County, N.C., that is now an Audubon Sanctuary. Courtesy, the Audubon Society

The first reference to the “Sampson blues” that I found in the state’s newspapers was a brief mention of them in the September 18, 1850 edition of a Raleigh newspaper, the Weekly Standard.

By 1868, a popular Baptist newspaper in Raleigh, the Biblical Recorder, even touted the “Sampson Blues” side by side with Albemarle Sound’s river herring as two of the state’s classic delicacies. (Quoted in the Tennessee Baptist, 19 Dec. 1868).

In the first years after the Civil War though, there was still only a very limited market for the berries. Locals foraged them, of course, and many a native son and daughter of Sampson County would never get over their nostalgia for the blueberry pies of their youth if they ever moved away.

Carolina bays are known for their rich biodiversity, including a stunning array of wild orchids and insectivorous plants such as Venus fly-traps, pitcher plants, and the tiny sundews seen here. This photograph was taken near Shaken Creek in Pender County, N.C. The sundews, only about an inch in size, catch insects in their sticky tentacles. Photograph by Christian Ziegler. Courtesy, The Nature Conservancy

But for a long time, the commercial market for the wild blueberries was confined to country people selling a bushel basket or two of the berries in nearby towns such as Clinton, Burgaw, or Fayetteville.

That all changed when a spur of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad reached Clinton, the seat of Sampson County, in 1887.

That was at a time when there were not yet cultivated (farm raised) blueberries available. As we will see later, a commercially suitable blueberry was not developed until the 1920s and ’30s.

But suddenly, with the arrival of the railroad, the blueberry foragers of Sampson County had a vastly larger market for the berries. At times, there seemed to be no limit to the demand: they filled freight cars with crates of them, and the trains whisked the blueberries off to Baltimore, New York, and Boston.

Up north, blueberry lovers eagerly awaited the arrival of the “Sampson blues.” They were the first or among the first blueberries to reach those northern markets in the spring. Looking at them as a precious delicacy, many customers were willing to pay top dollar for them.

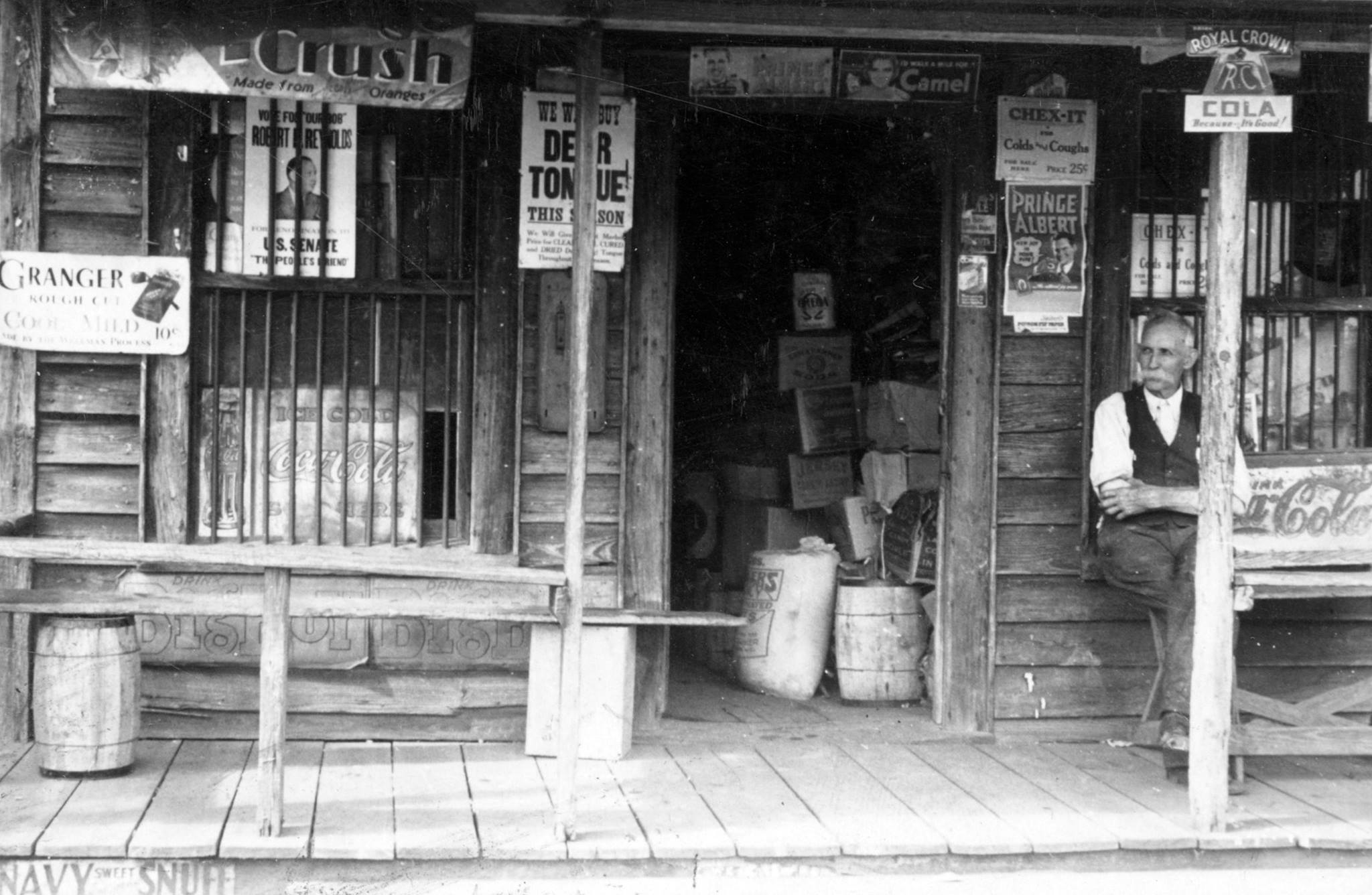

“Merchants like Tom Rich, old-time wholesaler, handle the crop as a sideline. Anytime during huckleberry season…., you can find huckleberries all around stores whose main business is flour, fatback, and cloth, crackers, farm implements, and darning cotton.”

Raleigh News & Observer, 17 June 1938

In Magnolia and Warsaw

I was not fully appreciative of the size of the wild blueberry trade in southeast North Carolina until I found notices such as this one in a July 2, 1879 edition of the Raleigh News & Observer:

“We learn that during the 40 days ending June 26th the present season, three firms at Magnolia have shipped in all 15,628 quarts of huckleberries to Richmond and Baltimore.”

At that time, Magnolia, in Duplin County, which is next door to Sampson County, was a small but busy market town that had grown up around a depot on the main line of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad.

Charles Corbett at his general store in Ivanhoe, N.C., 1938. His was one of many country stores in Sampson County where wild blueberry foragers could exchange their berries for cash or credit. Wholesalers would then collect the berries and ship them by rail to Washington, New York City, and even Boston. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Especially before the railroad reached Clinton, the town of Magnolia shipped large quantities of wild blueberries from the southern end of Sampson County.

Another decade later, on May 30, 1889, the Wilson Advance, in Wilson, N.C., reported:

“Mr. Isaac Down, of Warsaw, purchased a pair of mules, and a new wagon, on Tuesday … to haul huckleberries in Duplin and Sampson, for shipment North. The shipments from Warsaw last season aggregated forty thousand bushels, and the crop is equally promising this year. The old “Sampson blue” is regarded [in the] North as one of the finest table luxuries. The huckleberry industry is one of our most surprising and gratifying developments; a spontaneous money crop of wonderful profit and proportions.”

The writer’s surprise stemmed from the wild blueberries having been a local crop in Sampson County for ages, but not one that had any significant cash value until the railroads reached that part of southeast North Carolina and made it possible to send the fresh berries to northern markets.

Duplin County, N.C., is just east of Sampson County. The county has a long string of small towns– Wallace, Teachey, Rose Hill, Magnolia, Warsaw, and Magnolia– that developed around the completion of the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad in 1840. Map from Wikipedia

“The population swoops down on the huckleberry swamps”

In a rather exuberant article in the Wilmington Morning Post on June 23, 1901, I found a little more information about who was foraging the wild blueberries in Sampson County.

After comparing the wild blueberry boom that had happened in Sampson County to the “Klondike gold rush,” the Morning Post’s reporter observed that:

“they are gathered by a class of people who are so unfortunate as to be without farms, or any means of making a living, were it not for this `prize crop’ of Sampson County.”

He goes on to clarify, “This refers to widows and fatherless children.”

That was more than a bit of an overstatement, but it does convey how important the wild blueberry trade was to the poor and landless of Sampson County, which was most people.

Wild blueberries at the Clinton railroad station’s loading dock, 1938. According to the Raleigh News & Observer of June 19 that year, the berries were bound for New York City, Providence, and Boston.

Another visitor to Sampson County was no less excited about the wild blueberry trade. In Raleigh’s Farmer and Mechanic (July 12, 1910), that visitor wrote:

“When the huckleberry season arrives in Sampson County, other things stop and the population swoops down on the huckleberry swamps. . . . To the swamps the population goes, and soon after the exodus has begun, the railroads begin to do business, for the fame of the Sampson County big blue has gone out to the utter most ends of the territory that can be reached, and the express companies pick up huckleberries for Boston, New York, Washington, and any other place that can appreciate the luxury.”

Some written accounts make the harvesting of the wild berries seem like an almost idyllic summer picnic.

As best I can tell, those accounts were all written by journalists and visitors who never never had to forage the wild berries to make a living.

Few braved those pocosin thickets– hot, buggy, and thorny– on a June day just for the fun of it. And for those that did, I can assure you, it was no picnic.

“Out of the huckleberry swamps”

An interesting article in a 1915 issue of the Raleigh News & Observer gives us a sense of how important the wild blueberry trade had become to Sampson County and the extent that the county was associated with its wild berries.

In that article, the writer heralds the arrival of a new era in Sampson County’s history in which a variety of new agricultural and industrial interests would mark the local economy.

But in so doing, the writer also emphasizes just how thoroughly the county was associated with wild blueberries up to that time.

Dated August 22, 1915, the article reflected back on the early days of the 19th century.

“It is not more than a hundred years ago that if you mentioned Sampson County everybody laughed about the big blues and figured that all had been said.”

“For a century and a half,” the article goes on, Sampson County has “been winning distinction largely because it is the principal station on the huckleberry line.”

The story goes on to say:

“A stranger coming into Sampson County and expecting to find nothing but the huckleberry bushes that gave the county its first shove along the road toward fame finds himself bewildered by the multiplicity of things the county is doing for the advancement of its people and the surprise of the rest of the state. Sampson has stepped forth out of the huckleberry swamps….”

The notoriety of the “Sampson blues” can also be seen in this June 21, 1925 article in the Mount Olive Tribune as well:

“CLINTON. . . . The huckleberry is surely king in these parts. At the end of the 60 days of his reign, most of which is now past, the income from the huckleberry at this point alone will have been between $250,000 and $300,000.

“In addition to this will be shipments from a half-dozen or more shipping points that will increase the grand total by $100,000. The other day one farmer brought in 102 crates that sold for $8.50….”

On June 17, 1928, another article in Raleigh’s News & Observer gave a different view of how the wild blueberry trade actually worked in Sampson County at that time– and what a big business it had become.

According to the N&O, Sampson County’s foragers gathered some 80,000 crates of wild blueberries that season. Each crate carried somewhere between 24 and 32 quarts of berries.

A freight train leaving Clinton, N.C., ca. 1935-45. The arrival of railroads opened up large sections of Eastern N.C. to truck farming in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Sampson County grew famous for its wild blueberries, but many other communities became almost synonymous with a particular cultivated fruit or vegetable– Chadbourn and Mt. Olive with strawberries, Bogue Sound with watermelons, Rockyhock with cantaloupes, Aurora with white potatoes, Tabor City with sweet potatoes, among others. Photo courtesy, The Sampson Independent, 6 April 2022

The necessary investment was small, the article’s author, Ben Dixon MacNeil, went on:

“About all the expense attached to the growing and gathering of the crop is a small outlay for whatever ointment that is used to ward off the ravages of chiggers, and the customary cost for something to ship them in.”

Dixon also discussed the abundance of the berries and where they grew in Sampson County:

“Of the total area of the county a good third of the land must be unfit for agricultural uses, and most of the remaining third is naturally adapted to huckleberries. They grow naturally. If the frost doesn’t kill them, or if the spring forest fires do not ravage the forests and swamps, there will be berries….

“All that has to be done is go into the woods and pick them.”

By that time, large farmers and wholesalers were handling much of the wild blueberry crop, but as MacNeil’s article made clear, there was also still room for independent foragers too.

“There is no fixed practice to the system of picking and marketing. Some landowners allow anybody that wants to pick [to] go in and pick on shares. Others hire pickers and pay them a fixed sum per gallon picked.”

No doubt there was plenty of poaching too. At that time, Sampson County had no “public lands,” but I can’t imagine that discouraged dedicated foragers whose families had been hunting, fishing, and foraging in those swamp woods for generations, regardless who owned them.

In his 1928 article, Dixon indicated that the county no longer depended just on freight trains to carry the wild berry crop north. He estimated that as much half the crop had traveled north in trucks that year.

“The trucks run as far as Washington and Baltimore, and in some instances as far as New York. Express shipments are made to further markets.”

He added, “Almost everywhere the huckleberry is in higher repute than it is at home.”

“Somebody would set the woods on fire”

Another newspaper article, this one in the June 7, 1935 edition of the Durham Herald-Sun, provided a somewhat grittier sense of the wild blueberry business.

“If ever there existed a real “share-the-wealth plan,” this business of picking and marketing huckleberries could be placed within that scope. . .

“Young and old participate in the gathering of the berries. To some, particularly the youngsters, it is nothing more than a pastime because they can’t resist the delicious berries and eat them as fast as they are gathered from the bush.

“But those that go to the marshes with the view toward increasing their family budget, spend hours at their work. Expert pickers, when the high bushes are prolific with their fruit, are known to pick a crate (32 quarts) a day.

“Entire families can frequently be found filling tin buckets. [And] they have no trouble selling the berry. Country storekeepers, the landowner, and even traveling buyers are always ready to buy whatever quantity the pickers have, whether it be a quart or several crates.”

The writer, a journalist named R. C. Matthews, then went on to discuss how often wild fires threatened the wild blueberry crops.

He may not have been aware of it, but periodic wild fires are a distinctive and necessary part of the ecology of the Carolina bays and pocosin wetlands where the wild blueberries grew.

Or maybe Mathews did know it: in his story, he did observe that, after a wild fire, the wild berries returned more abundantly than ever within a couple of years.

He also makes an interesting observation.

In Sampson County, he wrote, “many of the landowners are reluctant to post the property on which wild blueberries grow.”

Of course, he meant post “no trespassing” signs on their property, which would make it an act of trespass to forage blueberries on their land.

“Pickers,”he continued, “are allowed to enter the marshes unmolested in any number of instances, for fear, as one farmer is reported to have said, ‘If I were to post my huckleberry land, somebody would set the woods on fire.”

Mathew acknowledges that he was not sure that his local sources were being truthful with him, but that comment rings true to me.

The Huckleberry Capital of the World

By the early 20th century, the wild blueberry trade in Sampson County had gained both a size and a kind of fame that I have never seen for a wild crop anywhere in the state of North Carolina.

By the 1930s, Clinton’s leaders were even touting the town as the “Huckleberry Capital of the World.”

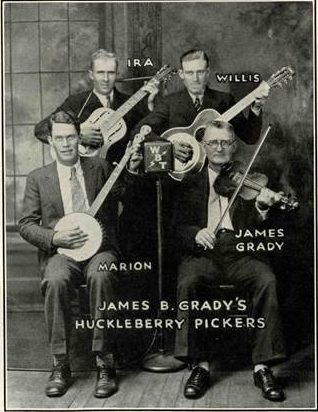

Fiddler James B. Grady’s Huckleberry Pickers were a string band from Clinton, N.C., ca. 1930-35. They played barn dances and community events and occasionally performed live on WPTF Radio in Raleigh. This photograph comes from one of WPTF’s program guides (courtesy of Joel W. Rose).

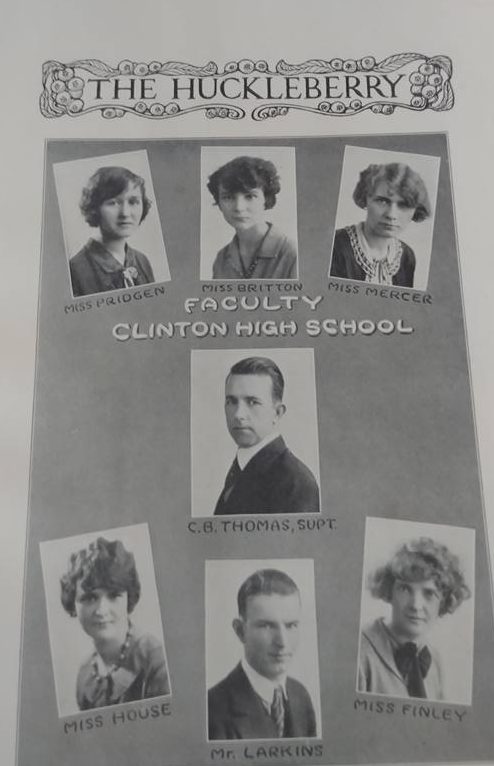

A page from the 1926 Clinton High School annual The Huckleberry. Courtesy, Jeff Mason

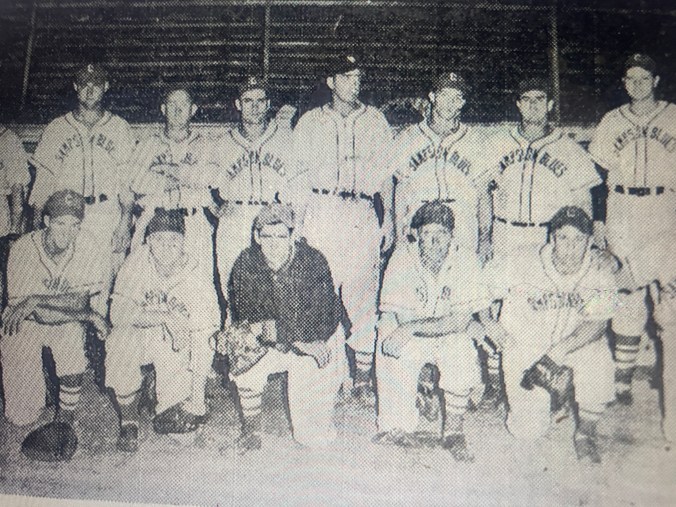

Starting line-up of the Clinton Sampson Blues, Clinton’s minor league baseball team. The Blues played in the Tobacco State League from 1946 to 1950. Photograph from the Carolina Annual (Tobacco State League Edition), n.d., in the collections of the Sampson County Historical Museum.

Indeed, the wild blueberry trade meant the world to many of Sampson County’s citizens during the Great Depression.

For the down and out, which was most people, it could mean having a little sidemeat with their collard greens or even being able to afford eyeglasses for a little girl or boy who could not go to school without them.

But even for some better-off farmers, the blueberry trade helped them make the transition from cotton farming to the wholesale produce business that Sampson County was and still is renowned for.

Even the farm family of U.S. Senator Lauch Faircloth, who was from Clinton, acknowledged the importance of the wild blueberry business to its success.

In a 1999 interview for the Southern Oral History Program at UNC-Chapel Hill, Sen. Faircloth described how the boll weevil and plummeting cotton prices had upended his family’s fortunes in the 1920s and ’30s.

Faced with those difficulties, he and his father took a stab at the wholesale wild blueberry business– and once they mastered the art of shipping the berries to northern markets, they very successfully expanded into the wholesale business with a large variety of farm produce.

The Last Days of the Wild Blueberry Trade

The trade in wild blueberries did not last much longer than the Great Depression, however.

I have not found any definitive historical sources that explain why Sampson County’s wild blueberry trade declined so steeply after World War II. However, I did read a few newspaper accounts that gave me at least a couple ideas.

First, even as early as 1920, an article in the Sampson Democrat (20 May 1920) speculated that the encroachment of farm fields into Carolina bays and other pocosin thickets might well mean the end of the “huckleberry woods” and “huckleberry ponds” where the wild berries flourished.

Those were tough times for a lot of the county’s farmers. After the First World War, small farmers– especially tenant farmers and sharecroppers– were leaving the land in droves.

However, many larger farmers were actually clearing more land and putting more acreage into cultivation, thanks in large part to a higher reliance on mechanization both in farming and swamp drainage.

That trend would continue throughout the 20th century, and one cost was a dramatic decrease in the prime habitats for the famous “Sampson blues.”

The ancient bald cypress of the Black River are some of the last old growth forest in Sampson County and are believed to be among the oldest wetlands trees on Earth. The oldest cypress on the Black have been dated as being more than 2,500 years old. Photo courtesy, The Guardian

Second, I can only make a conjecture here, but I think it is very likely that the rise of commercial blueberry farming in southeast North Carolina in the 1930s and ’40s crowded out the wild berries.

I mean that in two senses. In the first place, since commercial blueberry varieties favored the same kinds of soils and growing conditions favored by the wild blueberries, it seems probable that farmers expanded cultivated blueberry fields into the habitats for the wild berries.

In many instances, that land had not previously been considered suitable for cotton, tobacco, or other row crops, but the first generation of blueberry farmers discovered it was ideal for growing commercial berries.

African American workers harvesting blueberries at a large farm near Burgaw, N.C., June 1947. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

At the same time, I think it is also logical that the abundance, the uniformity of new cultivated blueberry varieties, and the relative ease of harvesting led wholesalers to direct their time and investments to farm-raised berries rather than the wild berries that were foraged in woods and wetlands.

The Early History of Commercial Blueberry Farming

Many different species of blueberries are native to North America, but it was not until around 1900 that a New Jersey farmer named Elizabeth Coleman White and a USDA scientist named Frederick Coville developed the first cultivated variety of high bush blueberry suitable for commercial agriculture.

In or about 1927, one of the early blueberry farmers in New Jersey, Harold Huntington, came south in search of farmland that would be suitable for growing an earlier crop of blueberries.

Twenty miles west of Burgaw, N.C., Huntington purchased a 1,640-acre parcel of land near Beatty’s Bridge on the Black River. It was the site of what had long been known as the Corbett Plantation, a former slave labor camp, and was located between the communities of Ivanhoe and Atkinson.

Huntington’s workers– nearly all African American men, women, and children– harvested the state’s first commercial blueberry crop in or about 1934.

By 1938, Huntington’s farm workers packed 12,000 16-pint crates of cultivated blueberries, which he shipped by rail to New York City and other northern markets.

Beginning at that time, blueberry farming expanded across a large swath of southeast North Carolina, but especially in the Carolina bays and pocosin lands of Pender, Sampson, Bladen, New Hanover, and Columbus counties.

For a time, the wild, foraged crop and the commercial farming of blueberries co-existed, but that did not last long.

Even as late as the summer of 1940, the N.C. Division of Conservation and Development issued 246 permits to blueberry pickers in the state-owned Bladen Lakes Resettlement Area (now called the Bladen Lakes State Forest) in Bladen County, N.C. The permits were free, but required a pledge to be careful about forest fires. (Salisbury Post, 25 June 1940) Photo courtesy, ArcGIS StoryMaps

“No substitute for the plain old huckleberry”

The last newspaper reference that I found to a flourishing wild blueberry trade in Sampson County was from the latter part of the 1930s.

Less than two decades later, newspaper accounts were already waxing nostalgic over the absence of the “Sampson Blues” in local markets and the end of Sampson County’s wild blueberry trade.

On August 3, 1950, for instance, The Greensboro Record, in Greensboro, N.C., ran an article on Sampson County’s wild berries with a headline that read, “Alas, The Poor Huckleberry.”

“As if the world situation isn’t bad enough . . .,” the paper’s correspondent wrote, only slightly tongue in cheek, I suspect, “the huckleberry seems to be going the way of the turpentine pine.”

The writer took some comfort in the growth of the cultivated blueberry industry in southeast North Carolina, but he did not give an inch on the wild berry’s superior flavor and how much he’d miss it.

As he put it, “Even if they are cultivated from here to yonder and grow as big as crab apples, they still won’t be the same. There is no substitute for the plain old huckleberry.”

I know they may not be as bountiful as they once were, but I figure there’s got to be some of those Sampson blues out there somewhere in the wilds of southeast North Carolina.

I reckon it’s too late for this summer, but I’m thinking next summer it’s going to be time to go looking for them, snakes and chiggers be damned.

David, I grew up in Clinton during the 1960-1970s, and I don’t recall anyone talking about wild blueberries or huckleberries. Commercial blueberry farming was another story, though; that seemed to be focused more around Faison, southern Sampson, and Duplin, from what I recall.

LikeLike

I saw a bunch of bushes at the old Boy Scout camp off Highway 24.

LikeLike

Wonderful piece. When I was a child growing up in Northern Wisconsin in the 1930s my parents used to drag us out to an area called the Barrens to pick wild blueberries. I always ate more than I contributed to the family bucket. Picking blueberries is pretty boring for a kid, especially after you have eaten too many.

LikeLike