This is the seventh photo-essay in my series “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.”

You can find my introduction to the series here.

In 1941, only weeks before Pearl Harbor, one of the NCDC&D’s photographers visited the wheelwright’s shop at the Hackney Wagon Company’s factory in Wilson, North Carolina.

His photographs give us a rare look at the master craftsmen at one of Eastern North Carolina’s oldest businesses.

Traditional wheelwrights were highly skilled woodworkers and blacksmiths. In these photographs, we can see the wagon factory’s craftsmen shaping and setting wooden spokes, firing rims, assembling and aligning hubs, and finishing and painting the final product.

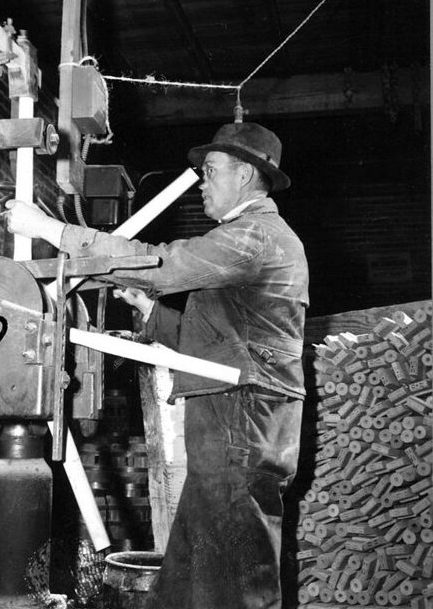

-1-

Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

In our first photograph, we see one of the company’s tradesmen assembling a wooden wheel in the wheelwright’s shop.

Almost a century earlier, in or about 1854, a master wheelwright named Willis Napoleon “W. N.” Hackney first opened a shop in Wilson, going into business with a carriage maker.

According to a reminiscence in the Raleigh News & Observer (25 April 1954), Hackney saw himself first and foremost as a craftsman. As the company grew, he hired others to do the shop’s office work, but stayed on the shop floor himself and continued to build wagon and cart wheels by hand.

His company’s wheels were built out of split oak and steel rims, and they could be found on farm wagons and horse-drawn buggies throughout Eastern North Carolina and beyond.

W. N. Hackney had to close his shop for a few years during the Civil War, but he expanded into making buggies and farm wagons after the war. By the early 20th century, the company was said to be one of the largest makers of buggies and wagons in the southern states.

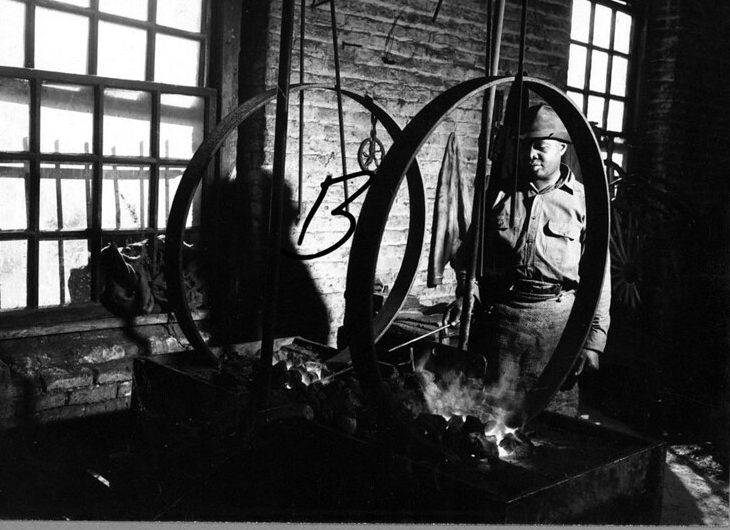

-2-

One of the company’s blacksmiths at work. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

The Hackney Wagon Company continued to build horse-drawn wagons and buggies well into the 20th century.

At their peak production in the early 1900s, the company’s tradesmen were turning out somewhere between 12,000 and 15,000 horse-drawn vehicles a year.

However, only a few years later, the Hackney family began to prepare for the great transformation in transportation that was coming.

In 1908, the Ford Motor Company had introduced the Model T, the first automobile that was mass produced and widely affordable to America’s middle class.

During and just after World War I, congestion on the nation’s railroads, federal investments in highways, and several key technological improvements in internal combustion engines all combined to drive the country further away from horse-drawn vehicles to automobiles and trucks.

Trucks began to replace not just local horse-drawn vehicles, but also began encroaching on the long distance freight trade that had previously relied on railroads and ships.

That was especially true after Ford introduced the Model TT, a truck equivalent of the Model T, in 1917.

By 1914, approximately 100,000 trucks were already on the nation’s roads. By 1920, there were a million.

The wheelwrights and wagon and carriage makers at the Hackney Wagon Co. saw all this coming.

In or about 1914, the company’s new president, T. J. Hackney, later remembered, “We saw that Ford had unhitched the horse and figured it was either ride on Ford’s back or get out of the business.” (N&O, 25 April 1954)

While continuing to produce farm wagons, the company increasingly turned toward building truck bodies and refrigerated trucks. In or about 1930, the company also began to produce what turned out to be a very successful and long-lasting line of school bus bodies.

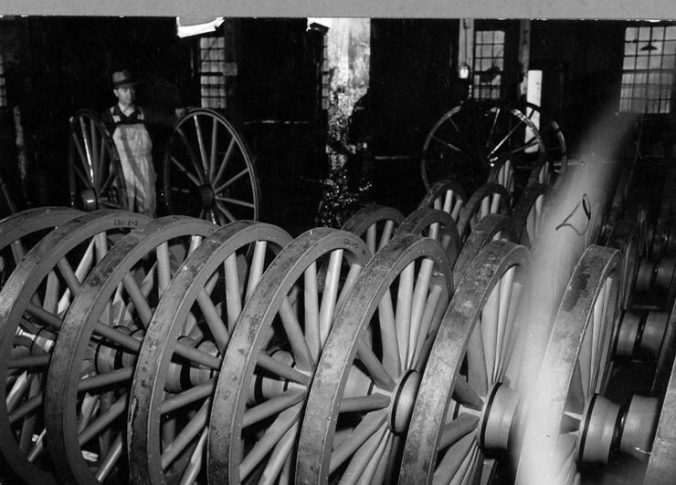

-3-

Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Unlike countless other businesses, the Hackney Wagon Co. survived the Great Depression and was apparently able to make its payrolls throughout those hard times, though only barely.

The company’s business then boomed again during the Second World War.

To an important degree, that was because of two factors related to the war.

First, the federal government awarded sizable military contracts to the company. As part of the nation’s Lend-Lease Program, the company was building wagon bodies for the British Army even before Pearl Harbor.

Later in the war, the company’s tradesmen built a variety of other products for the U.S. Armed Forces. They included mobile repair shops, Army and Navy buses, and vans custom-built to carry radar equipment, as well as ammunition chests and land mine crates.

Similar military contracts buoyed factories and mills across Eastern North Carolina, including scores of lumber mills, textile factories, shipyards, tobacco factories, and chemical companies, among others.

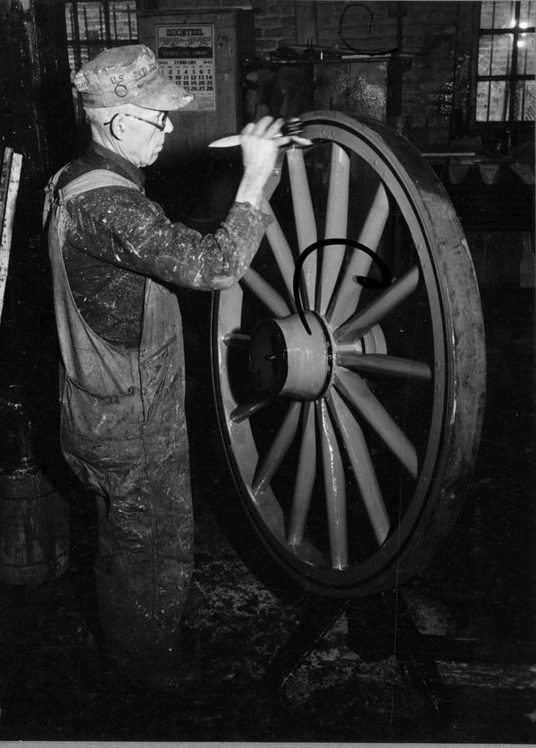

-4-

Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

The second reason behind the Hackney company’s expansion in the early 1940s also had to do with World War II, but in a different way.

Much to every wagon maker’s surprise, the war led to a brief but dramatic revival of demand for both horses and horse-drawn wagons and carts.

That rise in demand for horses and horse-drawn vehicles was the result of conditions unique to wartime. During the war, there was a shortage of rubber for civilian automobiles and trucks. Spare automotive parts were often impossible to get, and in 1942 the government placed a ban on all civilian car production so that that market would not interfere with automobile companies making bombers, tanks, and other military weapons.

Combined with the wartime rationing of petroleum, those factors fostered an interest in old ways of doing things, even though America’s industrial might and technological innovation was reaching its most dizzying heights at that moment.

During the war, demand for buggies, sulkies, and other horse-drawn passenger vehicles also skyrocketed. The Hackney company chose not to purse that market, however. The company’s leaders and workers seem to have kept their focus instead on war production and on the manufacture of wagons that were needed by the country’s farmers.

-5-

Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

The Hackney Wagon Company’s factory was located on an 18-acre site on the northern edge of Wilson, alongside the tracks of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad.

The company’s complex included factory shops that made school bus and other vehicle bodies, but I can see why the NCDC&D’s photographer may have chosen to focus on the wheelwright’s shop.

The wheelwright’s trade was one of the world’s oldest crafts. People had been making wooden wheels for horse, oxen, and mule-drawn carts and wagons for thousands of years.

By 1941, when these photographers were taken, the photographer had to know that the wheelwright’s craft belonged to another age and was increasingly out of step with modern times.

I can’t say for sure, but I wonder if the photographer felt that the company’s wheelwright shop had a special poignancy for that reason. He must have expected that the craft of making wooden wheels would not last much longer, except perhaps at museums and historic sites.

Putting myself in the photographer’s shoes, I also can’t help but wonder: who could resist watching these skilled tradesmen do these jobs they knew so well? And who would not want to admire the sureness of their hands and the knowledge of generations that they put into their work?

-End-

Great story. Thanks

LikeLike