This is the eighth photo-essay in my series “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.”

You can find my introduction to the series here.

In October 1942, one of the NCDC&D photographers visited soybean fields on a farm in Edgecombe County, N.C. He took a few photographs there, but then drove to Tarboro, the county seat, and lingered longer at the Southern Cotton Oil Company, a processing plant that was involved in a different and more rarely seen side of the soybean industry.

Soybeans have been one of Eastern North Carolina’s most important crops for more than a century, but the photographs he took that day are the only historical images I have ever seen of how workers turned them into the oil and meal that was, and still is, so much a part of daily life in the U.S.

For me, this set of photographs gives us a better feeling for how people lived, and what they did at work, and how our world is made.

Edgecombe County, N.C., 1942. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

We start with this close-up view of soybeans growing on the farm in Edgecombe County.

Anyone who has lived in or traveled through Eastern North Carolina is well acquainted with the sight of soybeans. The fields at my family’s little farm in Carteret County are full of them just now.

As I noted above, soybeans have been one of Eastern North Carolina’s most important crops for more than a century– and the state had a unique role in the growth of the soybean industry in the United States.

To quote a 2017 article by William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi, “North Carolina was the first state in America to grow soybeans commercially on a large scale, the first to crush domestically-grown soybeans, and the first to devise a farm implement to harvest them mechanically.”

-2-

Harvesting soybeans, Edgecombe County, N.C., October 1942. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Originally from China, soybeans were first grown in northeastern North Carolina soon after the Civil War.

In the beginning, the region’s farmers grew and harvested them by hand, and they did so not for the soybean plant’s seeds but for use mainly as a forage, hay, or silage crop for livestock– or sometimes simply for soil improvement. Like other legumes, soybeans improve soil quality by fixing nitrogen.

The invention of combine harvesters such as the one in this photograph was one of several technological advances that made commercial soybean farming possible on a large scale in the 1910s and ’20s– they combined reaping, threshing, and winnowing the beans into one process.

Some of the earliest mechanical soybean harvesters–and possibly the very first– were invented in and around Elizabeth City, a coastal town 80 miles northeast of the farm in this photograph.

Two Elizabeth City residents, George Pritchard and Leroy S. Gordon, are usually credited as the inventors of the soybean combine, though there was a whole cluster of soybean innovators in and around Elizabeth City in that day– and that was not an accident.

According to the 2014 article by William Shurtleff and Akiko Aoyagi that I mentioned earlier, William Morse, a soybean specialist at the USDA’s Bureau of Plant Industry, had begun focusing on the Elizabeth City area as an incubator for the nation’s soybean industry sometime around 1910.

In their article, Shurtleff and Aoyagi note that one of the local processing plants, the Southern Cotton Oil Company (more on it soon), had begun experimenting with producing soybean oil in 1913.

However, another local cotton oil company, the Elizabeth City Oil and Fertilizer Co., was evidently the first to do a really decisive test of the concept, crushing and expelling the oil from 10,000 bushels of soybeans in December 1915.

Other processing plants owners and soybean farmers were quick to take notice. Within a year, nine other mills in Eastern North Carolina were producing soybean oil. Five plants were manufacturing soybean harvesters-threshers. And with the new market for their crop, the region’s farmers dramatically raised their total acreage planted in soybeans.

North Carolina’s farmers were soon raising twice as many soybeans as farmers in any other state. For the next decade, the state’s farmers annually produced the majority of the nation’s soybean crop.

That was no longer true by the Second World War, when this photograph was taken. By then, the rise of soybean farming in the Midwest had swamped production on the East Coast.

Nonetheless, in many of the state’s tidewater counties, farmers still devoted more than a third of their crop acreage to growing soybeans.

-3-

Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

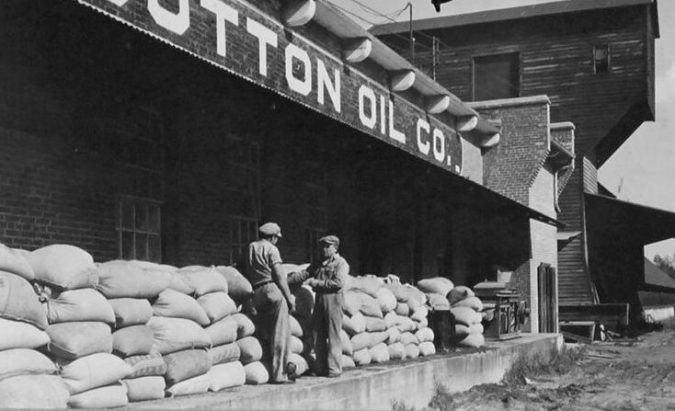

In this photograph, we see a pair of workers standing alongside hundreds of bags of freshly harvested soybeans at the loading dock at the Southern Cotton Oil Company’s processing plant in Tarboro, N.C.

Founded in Columbia, S.C., in 1887, the Southern Cotton Oil Co. had originally focused on producing cotton seed oil. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it grew into one of the country’s largest vegetable oil producers and had plants across the southern states.

If you haven’t heard of the company before, you have probably heard of some of the iconic cooking products that were made with its cotton seed oil. Among them were Wesson Oil and Crisco.

After the collapse of cotton prices in the 1920s, the Southern Cotton Oil Co.’s processing plants increasingly diversified into other kinds of agricultural processing– and one of the most important was processing soybeans into oil and into a dry meal (the dry residue left after the oil was removed) that was a popular feed for livestock and poultry.

In addition to producing soybean meal and oil, the Southern Cotton Oil Co.’s plant in Tarboro also still produced cotton seed meal as well as peanut meal, pulverized oats, fish meal, wheat bran, and alfalfa meal– all ingredients in feed for poultry, cattle, horses, hogs, and other livestock.

Early in the 20th century, American companies used soybean oil primarily in paints, inks, and in other industrial uses, not as a food ingredient for either people or livestock. That was just beginning to change at the time of the Second World War.

-4-

Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Here we see one of the Southern Cotton Oil Co.’s workers hauling bags of soybeans into the plant’s crushing room.

One of the things I appreciated about the photographer’s visit to the processing facility was the way that he followed the soybeans through the entire process of being turned into oil and “soybean cake.”

He kind of gives us a photo tour of the plant and its workers.

By the way, I should mention that a central figure in the recognition of the soybean’s potential as more than a forage crop in the U.S. was George Washington Carver. His research at Tusgkee Institute was critical in discovering the crop’s value as a protein and oil.

-5-

The Southern Cotton Oil Co., Tarboro, N.C., 1942. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

In this photograph, we see the next step in the process of making soybean oil and meal: one of the company’s workers is dumping soybeans onto a conveyor belt that will carry them up a chute to a hopper.

The soybeans will come off the belt at the top of the conveyor belt, then slide down through a trough where spiral blades will remove the chaff and dirt from them before they are crushed.

-6-

The Southern Cotton Oil Co., Tarboro, N.C., 1942. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Here we have an up-close view of the soybeans passing through the trough, sliding down toward the crushing machines.

-7-

Southern Cotton Oil Co., Tarboro, N.C., 1942.

The soybeans fell into the crusher, then passed through rollers that made the meal even finer.

-8-

Southern Cotton Oil Co., Tarboro N.C., 1942 Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

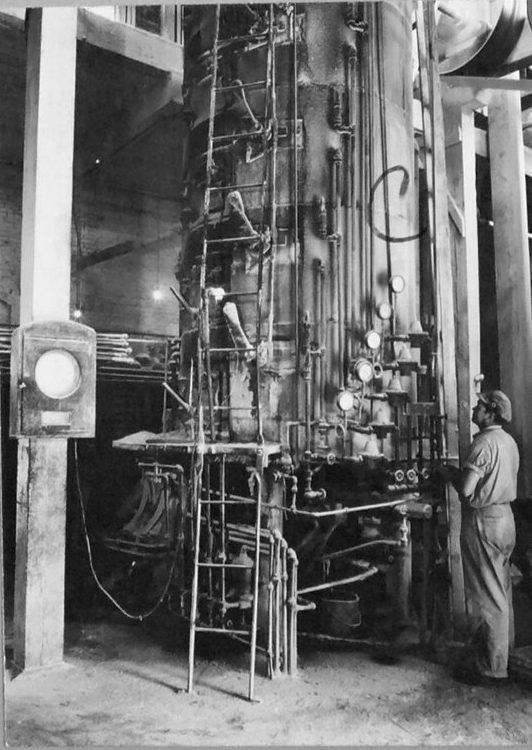

After coming through the rollers, the finely crushed soybeans went into a steam cooker.

-9-

Southern Cotton Oil Co., Tarboro, N.C., 1942. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

In the steam cooker, the soybeans were turned into a sodden mush that was then pressed to expel the oil.

-10-

Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

After the oil was expelled and piped into a holding tank, what was left was a dry soybean cake, which you can see sheets of here. The workers’ next step was crushing that soybean cake into meal.

-11-

Photo courtesy ,State Archives of North Carolina

Workers then shoveled the crushed soybean cake into sacks, ready for delivery to farmers and farm supply stores.

-12-

Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

At the same time, the company’s workers channeled the fresh soybean oil into a network of pipes that led to railroad tank cars outside. The man in this photograph is filling this car with the oil.

During the war, the country saw a steep rise in the demand for soybean oil as disruptions in shipping routes around the world cut off supplies of imported fats and oils.

That wartime disruption in supply lines led farmers to put more of their fields into soybeans and contributed to the oil’s widespread use in margarine, shortening, and as a substitute for imported oils in other food and industrial uses.

Today soybean oil is the most widely consumed vegetable oil in the U.S. and around the world.

-End-

Thank you Elizabeth Jackson for your help with this story, and good luck at Emory University!