This is the 15th photo-essay in my series “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.”

You can find my introduction to the series here.

Like all the photographs in this “Working Lives” series, this image is from the N.C. Department of Conservation and Development Collection at the State Archives of North Carolina in Raleigh.

In this photograph, we see a group of African American women and children harvesting strawberries in Wallace, N.C., in May 1944.

The photographer’s notes do not indicate whether they are local people or migrant laborers. Thousands of both were working in the strawberry fields of southeastern North Carolina during World War II.

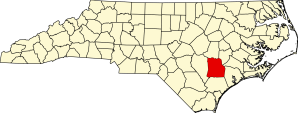

Wallace is located in the southern part of Duplin County, 40 miles north of Wilmington, N.C. Map courtesy, Wikipedia

A very similar photograph could have been taken in much of southeastern North Carolina in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

During those years, an extraordinary number of black workers– I would estimate somewhere between 25,000 and 40,000 annually at the industry’s peak– worked in the region’s strawberry fields.

The beginning of commercial strawberry farming in Eastern N.C., is a bit murky to me, but much of the historical evidence points to the vicinity of Mount Olive, on the border of Wayne and Duplin counties.

In that small town, a truck farmer and nurseryman named J.S. Westbrook began to raise strawberries and ship them by rail to markets in New York and other northern cities in the 1870s.

Other local farmers followed suit. By 1884, the Raleigh News & Observer (N&O) was reporting that truck farmers in Mount Olive and the neighboring market towns of Faison and Goldsboro had shipped at least 60,000 quarts of strawberries to northern cities that spring. (N&O, 24 July 1884).

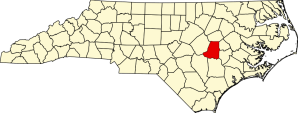

Goldsboro is the county seat of Wayne County, N.C. (shown here). Mount Olive is 15 miles south of Goldsboro, on the border of Wayne and Duplin counties, and Faison is another 8 miles south, on the border of Duplin and Sampson counties. Map courtesy, Wikipedia

That edition of the N&O also noted that, “Every point along the Wilmington & Weldon Railroad ships more or less fruit and their speciality is strawberries.”

Around that same time, a visitor observed that the harvest workers at Westbrook’s strawberry farm included “about 250 hands, white and colored, of all sizes from five to 60 years old.” (Goldsboro Messenger, 13 May 1886)

The Mount Olive area remained a large grower of strawberries well into the 20th century, but the center of the state’s strawberry industry began to shift a little south in the 1890s.

With Westbrook’s support and financial backing from a Chicago fruit company, a businessman named Joseph Brown recruited Midwestern and Western farmers to Chadbourn, a small town in Columbus County, N.C., that seemed to be fading away after its main business, a lumber mill, closed.

One of the new strawberry farmers was the Stole family, which relocated from Southern Illinois to Chadbourn in 1907.

More than half a century later, one member of that family, Glenn Stole, interviewed many of the early settlers and wrote an account of the early days of strawberry farming in Chadbourn.

In Chadbourn and Her Sunny South Colony: A Narrative History, Stole quoted a woman named Merle Penn whose family had fled a drought-stricken farm in Schuler, Nebraska, and moved to Chadbourn:

“The farmers in our section were desperate . . . [and] about that time my father read the glowing accounts of . . . Chadbourn. He read in Farm, Field, and Fireside, a farm paper, about the good land, the mild climate and abundant rainfall, and the money people were making growing strawberries.”

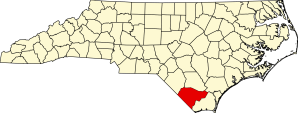

Chadbourn is in Columbus County, 60 miles west of Wilmington, N.C. Map courtesy, Wikipedia

One hundred and fifty farm families from some 15 states became the core of a rural planned community called the “Sunny South Colony” that was devoted to the growing and marketing of strawberries.

By the early 1900s, Chadbourn had grown into one of the country’s largest strawberry markets. In her truly stellar 2014 M.A. thesis at N.C. State, Stacey Nichole Roberts wrote:

“At its height in 1907, 1, 623 railcars containing 347,000 strawberry crates shipped [from Chadbourn] to cities across the north.”

On the market’s single busiest day, 180 railroad car loads– 1,152,000 quarts– of strawberries were shipped out.

Ms. Roberts goes on to say that as many as 15,000 black men, women, and children toiled in Chadbourn’s strawberry fields– the equivalent, she noted, to “half the population of Columbus County.”

“Legions of negroes have thronged here to pick and handle the crop,” Roberts quotes a May 1905 story in the Raleigh News & Observer.

It was a sign of the poverty and need of the day. They were only paid a dollar a day, but they still flocked to Chadbourn’s strawberry fields.

According to a history of Columbus County published in 1946, those field workers came not just from Columbus County, but also from 14 other counties in both North and South Carolina.

Chadbourn’s market declined drastically after the First World War, but was still part of what one newspaper called the state’s “Strawberry Basket” at the time that this photograph was taken in 1944.

Stacey Nichole Roberts’ thesis, which you can find here, includes an insightful look at the decline of the strawberry boom in Chadbourn. She chronicles several different reasons for the local industry’s decline, but I found her account of the refrigerated railroad car shortage of 1905 especially gripping.

In that account, Roberts tells the story of a harvest season in which a railroad company and a Chicago fruit company diverted refrigerated rail cars elsewhere and left Chadbourn without a way to transport a large proportion of its berries to northern markets.

As a result, tons of strawberries were left to rot in Chadbourn. To dispose of the rotten berries, locals dumped 62 freight cars full of them into White Marsh, a local swamp.

At least a dozen other rail cars loaded with overripe strawberries arrived in northern cities and had to be disposed of.

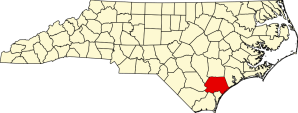

The other towns in the “Strawberry Basket” were Tabor City, Burgaw, Rose Hill, and Wallace.

The “Strawberry Basket” towns included Rose Hill and Wallace in Duplin County; Chadbourn and Tabor City in Columbus County; and Burgaw in Pender County (shown in red here). Map courtesy, Wikipedia

According to local lore, a farmer and storekeeper named Gabriel Boney first introduced strawberry farming to Wallace, where this photograph was taken, in the 1880s.

(Wallace was actually still called “Duplin Roads” or “Duplin Crossroads” at that time.)

In 1944, when this photograph was taken, Wallace’s strawberry market opened on the 17th of April. A few days later, the markets in Wallace and Chadbourn combined to ship out two thousand cases of strawberries in a single day.

In good times, strawberries were a lucrative crop. They were one of the few crops that could rival tobacco’s profits, but the work that went into growing strawberries also rivaled that which went into tobacco.

Planting, mulching, fertilizing, watering, weeding, and finally harvesting the berries often seemed like endless toil– and for the harvest workers, picking berries on one’s hands and knees in the sweltering Carolina sun was not something you did if you had any other way to making a living.

There were not, however, many other ways for a black family to make a living in much of Eastern North Carolina at that time.

That was the result of a quite intentional set of policies.

After black voting rights were eliminated in 1900, white leaders in rural Eastern North Carolina were left with a stranglehold on power, even in cities, towns, and counties with a large black majority.

Those white leaders were able to shape local tax, land, spending, and economic development policy to their own ends, with no requirement to consider African American aspirations or desires.

With that power, they fashioned local, county, and state policies that discouraged the development of a more diversified economy and undercut the development of rural industries that might offer higher paying, less grueling and safer jobs to African American workers.

In addition, white elected leaders in Eastern North Carolina– the state’s leaders did not allow any black individuals to hold political office in the first half of the 20th century– repressed public calls for greater investment in the region’s schools, opposed all civil rights legislation, and failed to support a stronger social “safety net” for those in need.

It is one of the greatest tragedies of the state’s history, and one with consequences with which we still live, but in all those cases, they crafted those policies precisely so that African American people like those in this photograph would not have better options and would remain in the fields.

-End-

The strawberries of wrath. Great piece. Thank you. Jack

LikeLike

HI David, Happy trails! I hope you all have smooth travels and a wonderful time in Portugal.

This article about strawberries is fascinating – I heard about tulips and blueberries and of course cotton and tobacco, but I knew nothing about all those strawberries! Or the people whose lives were engulfed in them.

Thank you so much for year another vignette from the amazing history of Eastern NC.

love, Lanier

LikeLike