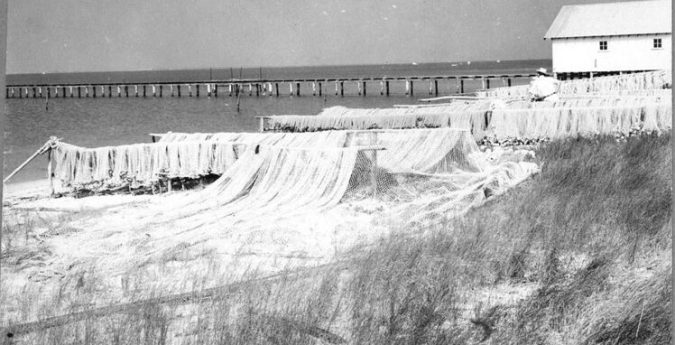

Harkers Island, N.C., 1944. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

This is the 18th photo-essay in my series “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.”

You can find my introduction to the series here.

In this photograph, we see a long line of fishing nets drying in the sun on Harkers Island, N.C., in the fall of 1944.

It is hard to see them, but there are two men talking in the midst of the net reels.

The photographer’s notes only identify one of the men– Stacy W. Davis, a local fisherman, charter boat captain, and fish dealer. That’s his fish house and dock on the far side of the net reels and fishing nets.

Capt. Stacy had built the fish house just before the war. He and his brother Leslie also owned the S. W. Davis & Brother Seafood Co. in Beaufort, on the other side of the North River.

The shoreline is beautiful, but in a way the tranquility of the scene belies the great upheaval that was happening on the island just before and during the Second World War.

When I was younger, old timers from Harkers Island often told me that it all seemed to start with the great hurricane of ’33, which is a story in itself and one that I think I’ll save for another time.

But not all storms come out of the Atlantic, and what happened over the next few years turned island life upside down more than any hurricane or nor’easter ever had.

Just a few years after the ’33 storm, in 1936, Harkers Island’s first road was paved: the age of automobiles and trucks was coming.

Three years later, in 1939, electricity arrived on the island, delivered via a submarine cable that ran beneath North River.

The stars would never be as bright again.

A year later, in the latter part of 1940, the biggest thing of all happened: workers finished building the first bridge from the mainland to Harkers Island. The bridge opened to the public a few weeks later.

That was on New Years Day 1941. Many a time, I have heard old timers say that it was the best and worst day in the island’s history: more than anything, it marked the end of one way of life, the dawn of another.

Then, of course, the war came. Young men and women went away to fight in distant lands and on distant seas. On the island, families crowded around radios to follow the news from places that few of us had known existed until that moment. Soldiers and sailors were everywhere.

An army camp was built on the island. Soldiers and sailors seemed to be constantly coming and going.

During the war, untold numbers of islanders also crossed the new bridge and went out into the larger world to take jobs at shipyards, military bases, and defense factories. Some commuted every morning to defense jobs as close as the Naval Section Base in Morehead City; others moved as far away as the big shipyards in Wilmington and Newport News.

The Great Depression had worn people down; suddenly there seemed to be work for any and all.

A hundred things about the war changed the island, but few things more than the War Department building the Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station only 25 miles away in 1942.

Nearly 10,000 men came together at at a remote crossroads on the south side of the Neuse River to build Cherry Point– carpenters, brick masons, ditch diggers, logging crews, railroad builders, and many, many others. Among other things, they laid enough concrete to build what is believed to have been the largest aircraft runway in the world at that time.

Most of those workers were fresh off the farm or right off a fishing boat.

When Cherry Point was finished, people came from all over the country to work there, and most particularly to find jobs at the base’s Assembly and Repair Department, a massive aircraft repair and refitting operation that relied on civilian workers and was usually just called “A & R.”

Those workers included many a Harkers Island fisherman. And when they left their boats and crossed the new bridge, they began a new life in more ways than they possibly could have imagined at the time.

Some of those islanders, my older friends on Harkers Island used to tell me, were saved by that trip to Cherry Point; others, lost.

For the island’s women, the coming of Cherry Point meant, if anything, even more. Because so many men had gone to war, the base employed thousands of women in jobs that would have traditionally fallen to men.

Those jobs ranged from aircraft painters to mechanics, PX and commissary managers to electronics specialists.

(My grandmother was one of those women. She lived on a farm in Harlowe, about halfway between Harkers Island and Cherry Point, and she found a job in A&R’s machine shop during the war.)

With the opening of Cherry Point, a daughter fresh out of school, perhaps still living with her parents, might suddenly be earning more than her fisherman father and all her brothers put together.

Of course, that changed things– maybe not right away, but over time.

Likewise, with the coming of the bridge and the war, a lad that had never taken to the water– and there were plenty of young men like that even on Harkers Island– suddenly had a chance for a different kind of life.

I guess what I am saying is that photographs tell some stories, but not others.

Our tranquil scene of fishing nets drying in the sunshine also does not really speak to what had been happening out at sea during the war.

By 1944, things had calmed down out in the Atlantic, but only a couple years earlier, in the first months after Pearl Harbor, the war had seemed much closer to Harkers Island that it did to most of the United States.

Many of the island’s young fishermen had gone into the navy and coast guard, and they were serving all over the world– but the U. S. Navy had also recruited the island’s fishermen for war duty closer to home.

As German submarines torpedoed merchant ships out in the Atlantic, one of the islanders patrolled the beaches out at Shackleford Banks, watching in the surf for the corpses.

Others, when they heard the explosions offshore, had the duty of taking their boats far out into the Atlantic to search for survivors and the dead.

Out in those seas, 15 and 20 miles off Cape Lookout, they often found themselves in a hellish seascape of charred hulls, burning oil slicks and scenes of which few of them would ever speak.

-End-

Special thanks as always to my friends at the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum & Heritage Center on Harkers Island.

Very interesting, as always. Thanks.

LikeLike

Thank you. Before I read this I was walking

LikeLike