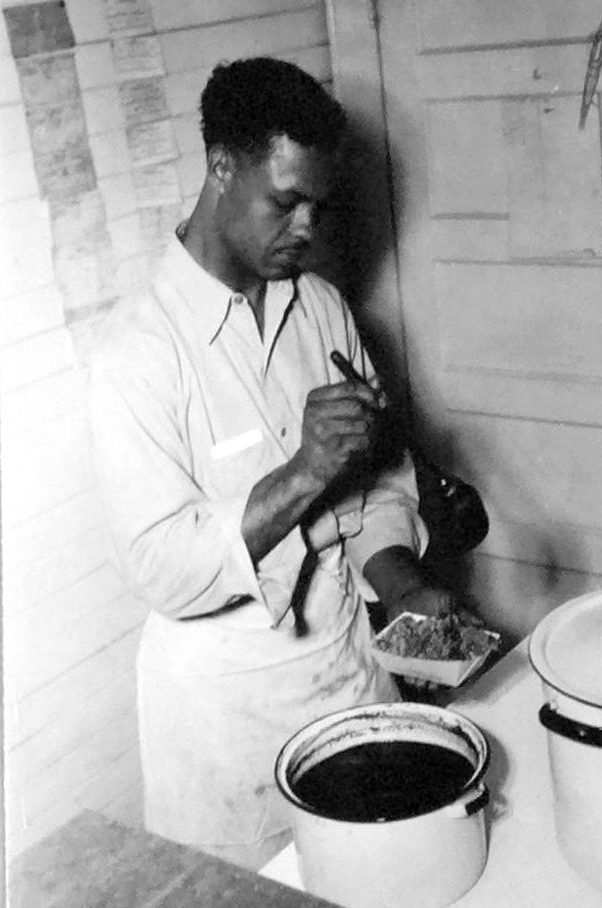

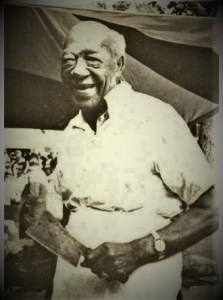

Adam Scott’s barbecue restaurant, Goldsboro, N.C., 1944. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

This is the 19th photo-essay in my series “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.”

You can find my introduction to the series here.

Like all the featured photographs in this “Working Lives” series, this image comes from the N.C. Department of Conservation and Development Collection at the North Carolina State Archives in Raleigh.

This photograph was taken during the summer of 1944 at the legendary barbecue restaurant that the Rev. Adam Scott and his family ran out of their home in Goldsboro, N.C.

I am not at all sure, but the young gentleman might be one of Rev. Scott and his wife Bessie’s sons or he might be one of the restaurant’s employees.

If our unknown cook is one of the Scotts’ sons, it was most likely the eldest, Alvin Martel Scott, who was 33 years old at the time.

At least two of the Scotts’ other sons were in the Armed Services at that time– Adam, Jr. in the Army, Hugh Victor in the Navy– and Martel often ran the restaurant when his dad was away.

He also oversaw the family’s other eating establishment in Goldsboro, a smaller cafe that catered to the town’s black citizens.

(A cafe could not serve black and white diners together in those days.)

In the coming years, Martel Scott patented the recipe for the family’s barbecue sauce and began the family’s very successful wholesale sauce business. You can still find Scott’s Barbecue Sauce in grocery stores today.

Scott’s Barbecue Sauce is believed to be the oldest commercially available barbecue sauce in the country. Photo courtesy, Jay Phillips

A Holiness Pentecostal minister, the Rev. Scott was born in 1890 and was barbecue royalty by the time that this photograph was taken.

Later that year, a local newspaper referred to the Rev. Scott as “a barbecue artist,” and it was far from the first time that he had garnered that kind of accolade. (Goldsboro News-Argus, 19 Dec. 1944)

At that time, he was not the only pit master in Eastern North Carolina that we’d call a “celebrity chef” today. There were others– Bill Melton and Buck Overton in Rocky Mount certainly had their fans– but even they did not enjoy the kind of otherworldly reputation that the Rev. Scott had.

By the Second World War, governors, senators, and tobacco barons had all beaten a path to the Rev. Scott’s backdoor, out of which he famously served his white customers.

A decade before this photograph was taken, he had even catered a barbecue for Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House. He served the ‘cue, sides, and cornbread in the Rose Garden, bless its dearly departed soul.

The Rev. Scott cooked in a tradition that dated back long before the Civil War, and one that was as distinctive to Eastern North Carolina as anything could be.

We still see it today, though rarely in a restaurant: whole hog, slow-cooked long hours in a pit over hardwood coals (the Rev. Scott preferred blackjack oak), basted with the region’s classic vinegar and red pepper sauce, and served chopped, preferably, if you’re like me, with a little skin.

Quite some time ago, back when he was still cooking pigs behind his family’s little cinderblock cafe in Wilson, I remember talking with E. R. “Mitch” Mitchell about the history of barbecue in Eastern North Carolina.

Mitch is a legendary pit master in his own right. Personally, I think he’d have given Rev. Scott a run for his money. But when I talked to him that day, he made clear that he knew and appreciated that he stood on the shoulders of pit masters such as the Rev. Adam Scott.

One of the things Mitch liked most about the region’s barbecue tradition, he told me, was the way it brought and still brings people together.

Even back in the days when Jim Crow was always working to tear us apart, good barbecue could upset the apple cart, he said, and he used Rev. Scott’s place in Goldsboro to illustrate his point.

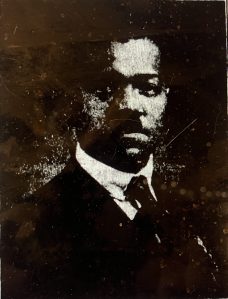

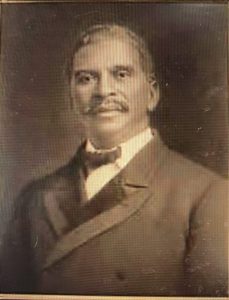

Adam Scott in 1925. At the time, he was 35 years old. The quality of the image could be better, but this is by far the earliest photograph that I have ever seen of the young barbecue master. It appeared in an advertisement that he placed in The Goldsboro News on April 15, 1925.

“I’ve heard the story of how Mr. Scott, the famous black barbecue chef over in Goldsboro, got started,” Mitch told me.

“Believe it or not, he started selling it out of his backdoor. I remember a white gentleman making a joke out of it, saying that white people used to have to go in the back door to be served.

“Which was an irony, but they didn’t mind, because the man was serving good barbecue. Whether they went in the front door, back door, whatever door, they got in line like everybody else.”

Remembering His Grandparents

The Rev. Adam Scott came from a family with deep, but largely unappreciated roots in the region’s African American communities.

To prepare this photo-essay, I spent a little time researching his family’s history.

For all the stories about the Rev. Scott that are out there today, I have never heard or read a word about his family’s past. I had no idea who “his people were,” as we say here, or where they had come from, or how they might have laid the groundwork for the Rev. Scott’s life.

I also knew very little about his early life, how he was raised, what life was like in Goldsboro when he was young, and how, even in his 20s, he had come to be, as one newspaper called him, “The Barbecue King.”

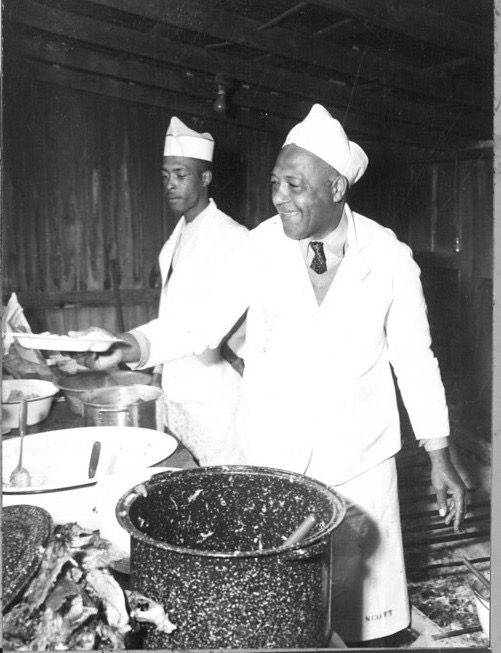

The Rev. Adam Scott at a barbecue in Wilson, N.C., 1948. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

So with that in mind, I did a little digging. I don’t think I have yet come close to the full story, but this is what I have learned so far.

To begin, I learned that the Rev. Scott’s grandfather, Charles A. Scott, was one of the most important black political leaders in Goldsboro and the rest of Wayne County in the tumultuous first decades after the Civil War.

He was known as “C. A.” Scott, and he was born in Johnston County, N.C., a little west of Goldsboro, in or about 1838.

Johnston County, N.C. The county seat Smithfield, is 30 miles southeast of Raleigh. Courtesy, Wikipedia

His father, whose name I do not know, had been born in Scotland. (That’s according to his son’s death certificate.) Evidently, C. A. Scott’s father was white; his mother, African American.

Adam Scott’s grandmother, Mary J. Scott, was also born in Johnston County, but was a little younger than her husband. According to census reports, she was born in or about 1846.

As best I can tell, both were born into slavery. Unlike some other counties in Eastern North Carolina, Johnston County did not have a large population of free African Americans prior to the Civil War.

I did not find either C. A. Scott or Mary J. Scott in the 1850 or 1860 federal census, and I should have if they were free.

However, I did find one document that suggests that their story may have been more complicated than that and certainly less clear.

When I located the death certificate for Joseph Scott, who was C. A. Scott and Mary J. Scott’s oldest son (and Adam Scott’s father), I discovered that he had not born in the South at all. He was born in Oberlin, Ohio, in 1860 or ’61.

If that is correct, then we know that the Scotts had left Johnston County and were in Oberlin prior to the Civil War or, at the very latest, during the first months of the war, when both Johnston County and Wayne County were still in the hands of the Confederacy.

How the Scotts– or at least Mary Scott– ended up in Oberlin at the time of Joseph’s birth is not clear to me.

However, I do know that the little town of Oberlin had a large community of free blacks from the South just prior to the Civil War and was a center for anti-slavery activism and the Underground Railroad.

Oberlin was one of the first places that the anti-slavery insurgent John Brown went to recruit guerrillas for the Raid on Harpers Ferry. This is an image of Lewis Sheridan Leary, one of three Oberlin men who joined his forces. Leary was a free African American from Fayetteville, N.C., who moved to Oberlin in 1857. Image courtesy, Oberlin College Archives

On the eve of the Civil War, when Mary and probably C. A. Scott were there, Oberlin was a well known refuge both for free blacks migrating out of Eastern North Carolina and for runaway slaves.

The Scotts could have been either, though I have as yet found no historical evidence that they were free before the war or that they had managed to escape from slavery in Johnston County.

The Struggle for Civil Rights

However C. A. and Mary Scott got to Oberlin, and wherever they were during the Civil War and the first years of Reconstruction, they had returned to Eastern North Carolina by the 1870s.

They had not returned to Johnston County, but had settled instead in Goldsboro, the seat of Wayne County, just to the east.

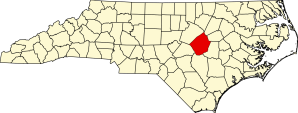

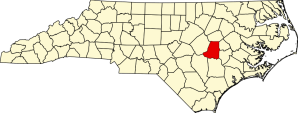

Wayne County, N.C. The county seat, Goldsboro, is 60 miles southeast of Raleigh.

None of the family appears in the 1870 census for North Carolina. However, at least C. A. Scott was in Goldsboro by 1874; a newspaper account mentions him in the town by that date.

A few years later, in 1880, the federal census confirms that the whole family was living in Goldsboro: C. A. Scott, Mary Scott, and their two sons, including Adam Scott’s father Joseph.

A carpenter by trade, C. A. Scott seems to have owned a lot and house in the town of Goldsboro.

By 1879, the family was also tenant farming on a 25-acre plot of land outside town.

Judging from newspaper accounts, C. A. Scott was in the thick of what often was a life and death political struggle for African Americans in Eastern North Carolina at that time.

On one side of the political spectrum was the Democratic Party, which at that time was a very different party than it is today.

Determined to do everything they could do legally and otherwise to curtail black voting rights and political power, Democratic leaders openly referred to their party as the “Party of White Supremacy.”

In addition to fighting to preserve white rule, the wealthy planters who controlled the Democratic Party also worked assiduously to fashion a new system of rural labor that, while no longer reliant on slave labor, mirrored in many ways the oppressiveness of slavery.

By all accounts, Adam Scott’s grandfather was one of the local black leaders who was standing up to “The Party of White Supremacy.”

He was passionate defender of black civil rights, a strong advocate for voting rights, and a leader in the local, predominantly black Republican Party of his day.

Those were dark and dangerous times. People were as divided over politics as we are today, and African Americans were working to be both as self-reliant as possible and to gain the full rights of citizenship.

You can see the battle lines being drawn in Goldsboro’s newspapers of that day.

On May 3, 1875, for instance, the conservative Goldsboro Messenger reported on a local biracial “civil rights meeting” that was chaired by C. A. Scott. According to the Messenger, both the black and white people at the meeting were “the enemy of the white race.”

In those days, those words– “the enemy of the white race”– were the kind of catchphrase that was used for those who failed to accept white supremacy as one of America’s founding principles.

C. A. Scott and the Exodusters

One of the most striking things that I learned about C. A. Scott was that he and his family nearly joined what was called the Exoduster Movement, also known as the Exodus of 1879.

The name “Exoduster” was originally applied to the estimated 40,000 African Americans who fled the states along the Mississippi River and relocated to Kansas in 1879.

This is an illustration of Exodusters passing through St. Louis on their way to Kansas in 1879. From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, April, 19, 1879. Courtesy, Missouri Historical Society

However, less known is the fact that tens of thousands of black tenant farmers and sharecroppers also fled the oppressiveness of life in Eastern North Carolina at that same time.

In the aftermath of the Compromise of 1877, a new wave of white racial violence swept the southern states.

No longer hamstrung by what had already been a relatively weak federal commitment to black civil rights, southern white legislators immediately began passing laws bent on reducing black tenant farmers to an even deeper state of peonage and to stripping all African Americans of their most basic rights of citizenship.

North Carolina was no different.

In amending the Landlord and Tenant Act of 1877 and passing the infamous county government act (which then, as now, centralized power over municipal and county governments in Raleigh), the white supremacists in North Carolina’s state legislature sought to put an end to the political and economic gains that African Americans had made since the Civil War.

To quote a gathering of the state’s black leaders in Raleigh in 1880, the new laws were “sucking the life’s blood from the colored sons of toil.” (They weren’t great for the “colored daughters of toil” either.)

In that first big wave of Exodusters in 1879-80, untold thousands of African Americans fled Eastern North Carolina. (A second big wave occurred a decade later.)

Some of the state’s Exodusters settled in Kansas, but far more of the region’s black families relocated to Indiana.

On January 15, 1880, the Wilmington Morning Star reported that as many as 6,000 black tenant farmers and farmworkers had already fled Wayne and Johnston counties and gone to Indiana.

A little to the east, and a few weeks earlier, the Kinston Journal (4 Dec. 1879) reported that “exodus feeling is worked up to a fever heat, and in some sections nearly all are leaving.”

“We Might as Well be Vagabonds”

C. A. Scott seems to have been a leading figure in the Exoduster Movement in Wayne County.

Late in the fall of 1879, according to newspaper accounts, a group of Goldsboro’s black citizens chose him to go to Indiana and Kansas and investigate what life was like for black emigrants there.

Evidently, they were considering emigration en masse.

C. A. Scott made the trip after he got his crops in that year. While in the Midwest, he met with local black families who had already left Wayne County.

Either while he was on that fact-finding mission or just after his return to Goldsboro, he was interviewed by a correspondent for the New York Tribune, one of the country’s most influential newspapers.

In that interview, C. A. Scott was asked why so many black tenant farming families were looking to get out of Eastern North Carolina.

C. A. Scott, it turns out, was a plainspoken man:

“Well, we have no chance in the world, and the colored people are getting desperate,” he told the Tribune’s reporter.

Back in Wayne County, he went on to say, his tenant farming neighbors would have answered the reporter’s question by saying, “We have been free 15 years. .., we have been cheated out of our wages; we don’t know how it is, but when the year is up we have nothing.”

The hardship, he said, was almost beyond belief.

C. A. Scott observed that many black tenant farmers could not afford to clothe themselves or their children decently.

“When we come into town, we have to hold our hands before us to hide our nakedness,” he told the Tribune’s reporter, again speaking for his neighbors back home.

No wonder, he said, that so many contemplated leaving tenant farming and moving, whether that was to Indiana or Kansas or even just away from their tenant farms to towns and cities in North Carolina– anything to get away from the oppressiveness of tenancy.

“We might as well be vagabonds in town where we can now and then pick up an odd job as to work nights and days and Sundays and get nothing from it,” was their thinking, C. A. Scott explained.

In that interview, C. A. Scott confessed that he and his wife were also considering emigration, but that his wife had friends in the state of Ohio and that they might go there instead of Kansas or Indiana.

The Scotts did not leave Goldsboro. In the interview, C. A. Scott explained that his family’s departure hinged on being able to sell their home and lot in Goldsboro. Maybe that is why they did not go to Ohio. With so many black families leaving at that time, they may not have been able to get a reasonable price for them.

All I know is that C. A. Scott and his wife and children stayed in Goldsboro, and I hate to think of the hole that would have been left in Eastern North Carolina’s barbecue history if they had gone.

Hopes for Better Times

A year after C. A. Scott’s journey to the Midwest, he and his son Joseph J. Scott– Adam Scott’s father– affirmed the family’s decision to remain in Goldsboro by establishing a house moving business.

I assume that they continued to farm and take on carpentry jobs as well. At that point, the U. S. census listed all three men in the family as carpenters– C. A. Scott, Joseph and Joseph’s younger brother.

Eventually, Joseph, who grew into a very big man, took over the house moving business and made it his own.

Housing moving was no mean feat in those days. House movers usually did their job with only a pair of mules, a winch, a small gang of strong young men and an abundance of ingenuity.

Word on the street was that “Joe” Scott could move any building anywhere. He worked throughout Eastern North Carolina, as well as in South Carolina and maybe in Virginia, too.

In so doing, he became something of a legend, which is something I have seen more than once with house movers back in those days, so marvelous did their work seem when it was done well.

I have not yet learned very much about the Rev. Scott’s mother, though I hope to learn more in the future. I know that her name was Lucy Hobbs, and I have one good, but unconfirmed account that indicates that she kept an independent household a block or two away from Joseph Scott’s residence.

In that part of Eastern North Carolina, hopes for better times rose with the coming of the Knights of Labor, the spread of Populism, and the landmark elections of 1894 and 1896.

State Historical Marker, Tarboro, N.C. Photo by Mike Wintermantel. Courtesy, HMdb.org

Those hopes were smothered by the white supremacy movement of 1898-1900. Beginning in the summer of 1898, a reign of terror spread across the land, elections were stolen, people killed. No black citizen was safe, and neither were the white citizens who stood by their side.

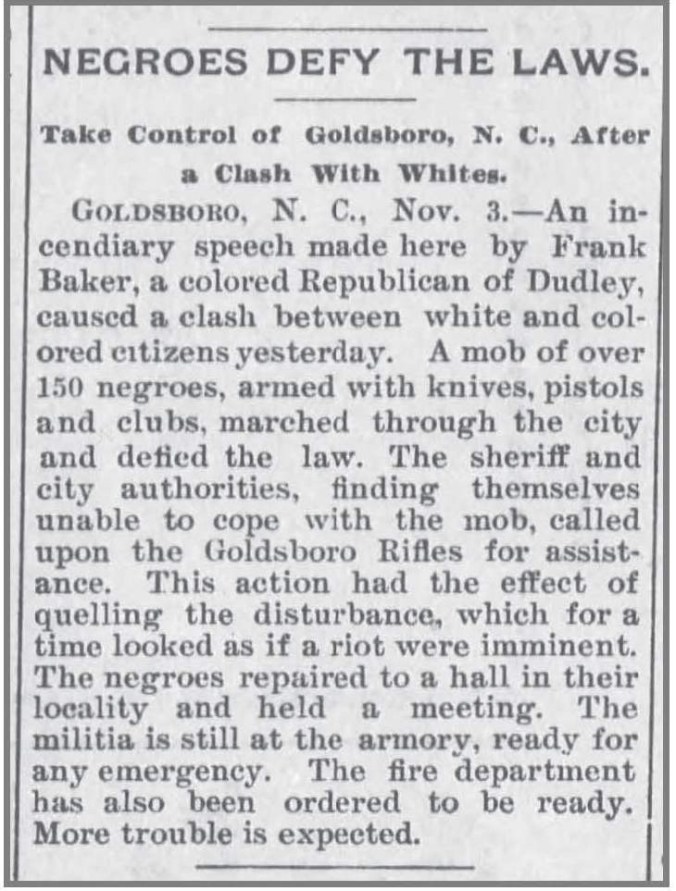

The rising racial tensions in Goldsboro were already evident when this article appeared in the Daily Reporter in Independence, Kansas on Nov. 4, 1896 and in newspapers across the country. What really happened is far from clear, but afterward local black leaders such as the Rev. Clarence Dillard and undertaker Arnold Sasser– whom some credit as the Rev. Scott’s mentor in the barbecue pit– felt obliged to write a conciliatory letter to the Daily Argus in response to what they called the “riot.” Whatever event sparked the incident almost certainly had to do with the 1896 election and white resistance to the growing success of the black and white “Fusion ticket” in the state’s politics. Frank Baker, by the way, was assassinated four months later. Once again, many thanks to Lisa Y. Henderson’s astonishingly good blog on the region’s history and genealogy for her research on this subject. You can find her blog entry “Pre-election Street Fracas” here.

Born in Goldsboro in 1890, Adam Scott grew up in those times. Even as a young boy, he had to have seen what was happening: it was not something that a mother and father could hide from a child.

That was especially true because Wayne County was one of the epicenters of the state’s white supremacy movement.

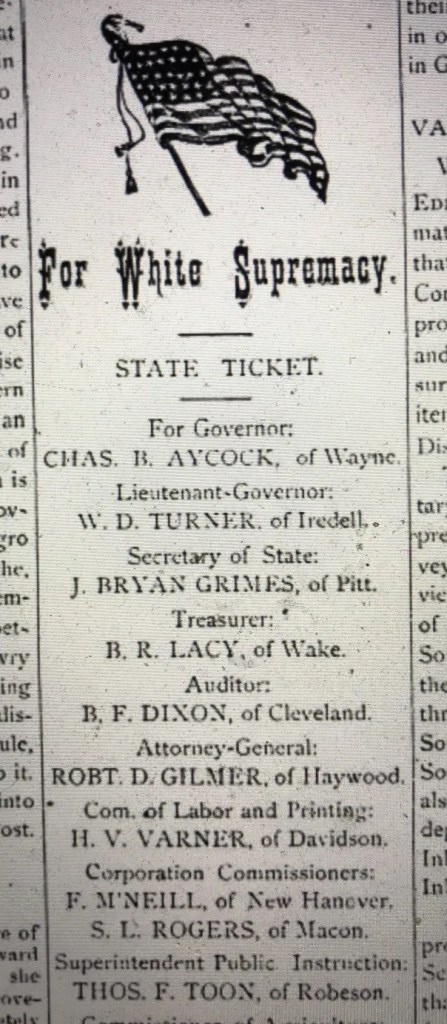

Wayne County’s Charles B. Aycock and his law firm were the very beating heart of the white supremacy uprising.

Aycock, who grew up on a farm north of Goldsboro, surrounded himself with armed vigilantes called Red Shirts and was elected governor in 1900 on what he called the “White Supremacy Ticket.”

Wayne County was also the site of one of the largest white supremacy rallies in North Carolina history.

Charles B. Aycock headed the state ticket “For White Supremacy” in the North Carolina election of 1900. From The Eastern Courier, June 1900.

That event occurred on October 28, 1898. Its organizers called it a “White Supremacy Convention.”

At that rally, William A. Guthrie, a leading tobacco industry attorney from Durham, was one of the speakers.

Standing before some 8,000 supporters, with Charles B. Aycock at his side, Guthrie proclaimed:

“The Anglo Saxon planted civilization on this continent and wherever this race has been in conflict with another race, it has asserted its supremacy and either conquered or exterminated the foe. This great race has carried the Bible in one hand and the sword [in the other]. Resist our march of progress and civilization and we will wipe you off the face of the earth.”

That was the tenor of the times. That was the world in which Adam Scott grew up.

Beginnings

Growing up in Goldsboro, Adam Scott attended the Goldsboro Colored School, a beloved African American institution where the Rev. Clarence Dillard was the principal.

Born in Alabama just before the Civil War, Clarence R. Dillard went on to study at Howard University and earned his doctoral degree at Lincoln University. In addition to serving as the headmaster at the Goldsboro Colored School, he was also a prominent Presbyterian minister in that part of Eastern North Carolina. Goldsboro’s first high school for African-American students was named after him in 1924. Photo courtesy, Dillard/Goldsboro Alumni & Friends, Inc.

Adam Scott’s grandfather, C. A. Scott, had helped to establish the school back in the 1880s. He had also served as the first president of the school’s board of trustees. (Goldsboro Star, 25 June 1881)

Sanctuary of the First African Baptist Church, Goldsboro, N.C., 1927. The church burned in 1973 but was rebuilt and is still very much active today. From the Goldsboro News-Argus, 17 March 2013

I am not sure, but I believe that young Adam was raised in his grandparents’ church, the town’s First African Baptist Church. Goldsboro’s black residents had founded the church in 1864, when most of them were still enslaved.

The First African Baptist Church in Goldsboro played a central role in the history of the African American Baptist tradition in North Carolina. Among other things, it was the site, in 1867, of the founding of the General Baptist State Convention of North Carolina, the state’s oldest black Baptist association.

Young Adam Scott and Bessie Bright were married on September 14, 1911. According to a later interview with a reporter from Norfolk, Va.’s black newspaper, the New Journal and Guide (3 Sept. 1938), that was also the year that Adam Scott held his first cooking job.

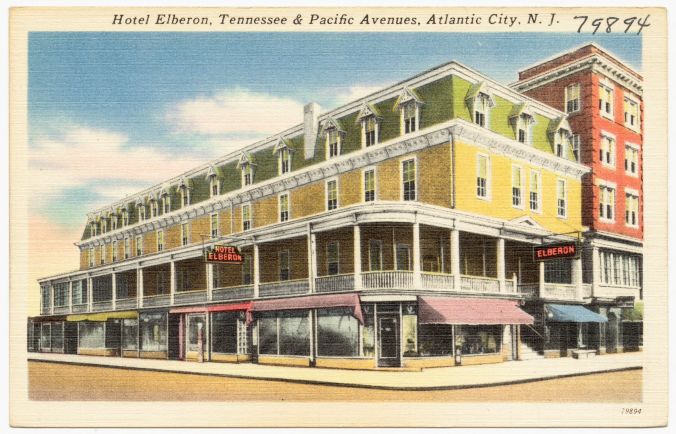

That job was not in a barbecue pit or even in Goldsboro, but at the Elberon Hotel in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

At that time, resort hotel managers on the Jersey Shore recruited large numbers of mostly seasonal workers in African American communities below the Mason Dixon Line.

They understood that many young black men and women in the South yearned for almost any job that was not in a cotton or tobacco field. Most were summer jobs, though I imagine that some summer employees had opportunities to stay and work there year-round.

The Elberon Hotel, Atlantic City, N.J., ca. 1930-45. Postcard from the Tichnor Brothers Collection, Boston Public Library

“Since that time he has held numerous jobs in kitchens at other places and even including Goldsboro,” the New Journal and Guide’s reporter wrote.

A few years later, Adam Scott catered his first barbecue in Goldsboro. According to family lore, that was for the Algonquin Club, a whites-only social club that was located on the top floor of the Borden Building.

As the story goes, the club’s regular pit master, an older, African American gentleman named Arnold Sasser, fell ill and at the last minute was not able to cook for a large gathering of the club’s members and guests.

Adam Scott, who was the club’s caretaker at that time, stepped in.

When and where he had first learned how to cook a pig is unclear.

Some accounts say that Arnold Sasser had taught him the ropes. The 1900 census lists Sasser as an undertaker by trade, but it would not be surprising if he catered barbecue events on the side.

Sasser may well have been Adam Scott’s mentor. But I also would not be surprised if the Rev. Scott learned like most people did then and do now: by watching pit masters work from the time they were little children, then beginning to help a bit and gradually gaining mastery of the craft.

“For Broken Hearts It’s Healing”

Over the next 10 or 15 years, Adam Scott became the most renowned barbecue caterer in Eastern North Carolina– but like most barbecue pit masters then and now, he did it as a side job.

Community barbecues were incredibly common in and around Goldsboro. The men– almost always men– who were the pit masters did their work at harvest time, when farmers wanted to show their appreciate to all those who had helped them to bring in their crops.

A good pit master would also do his work at community fundraisers– such as the one that was held in Goldsboro’s courthouse square in the summer of 1916 for flood victims in Western North Carolina.

Those pit masters would also cater events at Christmas, for fraternal groups such as the Masons, for social groups like the Algonquin Club, for reunions of all kinds, for church revivals, and for many other kinds of occasions.

All I am saying is: for the Rev. Scott to stand out among the many, many capable souls who knew their way around a barbecue pit in that part of Eastern North Carolina really says something about his ‘cue.

He had to be special. And in my experience, that usually means that he could cook barbecue that would make you swoon and he carried himself in a way that lifted up the people whom he was feeding.

Even as early as the 1920s, the citizens of Goldsboro acted as if he was a national treasure.

Some, like this anonymous individual writing in The Goldsboro News on June 3, 1928, were even moved to pen a few lines of poetry:

Adam Scott you cook it hot

You cook it good

without no pot

And in the region ‘neath my chest

I have the grandest feeling

For well I know you fix it best

For broken hearts it’s healing.

Barbecue Pit and Church Pulpit

While catering barbecues in Goldsboro and far beyond, the Rev. Scott also put his hand to whatever else he could do to make a living for his family.

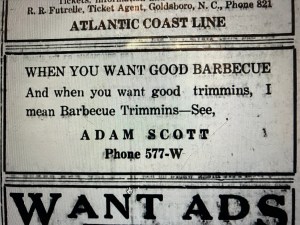

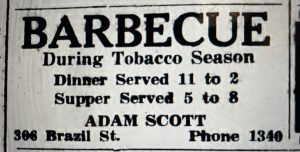

Advertisement for the Rev. Scott’s catering services, Goldsboro News of July 17, 1928.

In the 1910s and ’20s, he was employed at restaurants, a local sawmill, and at a men’s clothing store. For several years in the early 1920s, he also owned and operated a laundry business in Goldsboro.

According to the New Journal and Guide, a job at a Goldsboro bank was a turning point for him.

To quote the New Journal and Guide:

“From 1927 to 1931 Rev. Mr. Scott worked as a messenger at the Branch Bank and Trust Company…, while he still kept his activities as a caterer to families all over the country. He soon realized that there were no other possibilities for a man of color in the bank and determined to try something for himself. Thus he began a small business of selling barbecue which has outgrown any thoughts in mind at its beginning.”

I am a little fuzzy on the dates, but as best I can tell Rev. Scott and his family opened the restaurant in their home on Goldsboro’s Brazil Street sometime between 1931 and 1933.

At first, according to the 1938 interview in the New Journal and Guide, the Scotts cooked only two hogs a week. They cooked them overnight on Fridays, then served plates of ‘cue out their back door on Saturdays.

Soon he was cooking more hogs and serving ‘cue out of the family’s home an extra day a week.

A view inside the Scott family’s barbecue pit, 1944. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

As best I can tell, the family’s children all helped at one time or another. The Rev. and Bessie Scott had six children in all: four sons– Alvin, Edwin, Hugh Victor, and Adam Jr.– and two daughters, Pauline and Miriam.

As the popularity of the Scott family’s barbecue grew, the Rev. Scott expanded further, until he was cooking four to seven hogs a day and serving barbecue plates to hundreds of customers every day of the week except Sunday.

On Sundays, the Rev. Scott was not exactly resting either. By the 1930s, he was a central figure in the United Holy Church of America, a Holiness-Pentecostal religious body that had been founded in North Carolina in 1886.

Every Sunday he closed his restaurant, the New Journal and Guide’s reporter noted approvingly, and devoted himself to his ministry instead of barbecue.

When he was interviewed by the Journal and Guide in 1938, he was serving as pastor at three churches:: the Gospel Light Holiness Church in Mount Olive and two churches east of Goldsboro, one in La Grange and the other in Falling Creek.

In that interview, the Journal and Guide noted that the Rev. Scott also served as the United Holy Church of America’s general treasurer at that time.

In addition to the family’s restaurant, the demand for the Rev. Scott’s catering services grew steadily. In the 1920s and ’30s, he was throwing barbecues throughout that part of Eastern North Carolina and far beyond.

In those years, some of the state’s foremost political and business leaders employed him to cook for their barbecue events.

Two of North Carolina’s wealthiest men, R. J. Reynolds, Jr., son of the giant tobacco company’s founder, and Robert Hanes, the longtime president of Wachovia Bank, were among them.

Both men resided in Winston-Salem, N.C., 150 miles west of Goldsboro. But if the old accounts are to be believed, the Rev. Scott practically wore a path between the two cities.

Those were, needless to say, profitable endeavors.

“On occasion for just one cooking, he received more than he received for four years work as messenger at the local bank,” the New Journal-Guide wrote of him.

Over the years, comedian Bob Hope and local movie starlet Ava Gardner were among the many celebrities who enjoyed a plate of the Rev. Scott’s barbecue.

And as I mentioned earlier, the Rev. Scott prepared a barbecue dinner for President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House in 1933.

The Scotts may have stayed in touch with the Roosevelts. Five years later, the May 13, 1939 edition of the New Journal and Guide reported that Bessie Scott, the wife of the Rev. Scott, was chaperoning the glee club from Dillard High School (which had evolved out of the Goldsboro Colored School) on a trip to Washington, DC.

While on that trip, the students sang for Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt at the White House.

“The List of Strange Things that Happen in the South”

In the summer of 1942, a young African American journalist named A. Alexander Morisey wrote a column about his visit to the Rev. Scott’s home in Goldsboro.

I found Morisey’s column in the August 29, 1942 edition of the New Journal and Guide, but it probably ran elsewhere as well.

By that time, the Scotts had closed in the family’s back porch and turned it into a dining room. Instead of just serving take-out plates and sandwiches out the back door, they could seat customers in their home.

In the August 29, 1942 edition of the New Journal and Guide, Morisey wrote:

“To lots and lots of folks Goldsboro, N.C., is synonymous with good barbecue and we are one of those folks. Each and every time we set foot in the city, we can’t resist the impulse to visit our friend, the Rev. Adam Scott, and partake of that delectable barbecue he roasts.”

Morisey added, “There’s nothing better than that delicious barbecue with hot cornbread right out of the oven and coleslaw….”

From the Goldsboro News-Argus, 6 Sept. 1938.

Morisey observed that the way that black and white customers were served at Scott’s home took some getting used to.

“Oddly enough, Negroes . . . are served in the private dining room of the Scotts’ home and enter by the front door while white patrons use the back door which opens to the large dining room where hundreds are served daily.”

“Add that to the list of strange things that happen in the south, where segregation is practiced,” Morisey wrote.

Needless to say, the racial code of the South decreed that no black person could enter or leave a white person’s home through the front door, but had to “go around back.” Seeing Rev. Scott’s white customers “going around back” was something of a novelty to Morisey and to many a white visitor as well.

Of course, in those days, the Rev. Scott could never have permitted black and white people to sit down and eat together, either in the restaurant part of his family’s home or in his family’s private dining room. Barbecue is a balm for many things, but even good ‘cue can’t heal all things.

Coals Glowing in the Night

I am of an age that I remember the Scott family’s barbecue restaurant before it closed for the first time in 2001.

After that closure, his family re-opened and closed the restaurant again a couple more times before shutting the doors for good and just focusing on making and selling their barbecue sauce.

The Rev. Adam Scott himself had passed away in 1983 at the age of 93. His grave marker at Elmwood Cemetery does not mention his legendary status as Eastern North Carolina’s “barbecue king.”

It refers instead to his devotion to his faith and to his church: above his name on the stone is the single word “Elder.”

I visited his grave the other day when I was passing through Goldsboro.

While I was there, I thought about all that I had learned about him and, to borrow that old expression again, “who his people were.”

I thought about his grandparents’ life in the Slave South, their struggle for civil rights in the 1870s and ’80s, and the Exodusters and that journey to Indiana and Kansas that his grandfather made in 1879.

I thought about the shadow that fell over the land in 1898.

I thought about his father and mother too, and how his father made his living with his hands, building things and moving houses, and the skill that took, and the exactness and attention to detail it required– and I wondered how they shaped the Rev. Scott and how he went about his life.

I thought too about Lucy Hobbs, his mother about whom I have so far found out so little. Had she first shown him the way around a kitchen, and had she taught first taught him how a good meal feeds both the body and the spirit?

Was that why he was first hired as a cook at the Elberon Hotel?

I also thought a lot about the Rev. Scott’s Sunday mornings, when he drove out to the little country churches where he was pastor, and where the pews were filled with souls hungry for more than barbecue.

How I would have liked to spend a night cooking a pig with him. It is always a special thing anyway, but if I were with him, I would have cherished the chance to sit by the pit all through the night and watch the embers burn and talk about barbecue and matters of the soul.

I would have had many questions about that craft of his, that slow cooking over a fire that had been done for unknown ages. But I also would have liked just to see how he moved when he was working, how his hands tended the coals, how he shifted the oak around, raised and lowered the flames.

In my mind’s eye, I see him in that pit, the coals glowing, the hog roasting slowly, the stars above. I hear the murmurs of people, men probably, talking and telling stories around the fire, and when the rest are gone, late in the night, just a single solitary figure, maybe saying a prayer for us all.

The Rev. Adam Scott. Courtesy, The Scott Group

Incredible story. Thank you.

LikeLike

Fascinating back story, David! My grandmother was born in southern Wayne County, and several of her father’s kin — including J. Frank Baker — were involved in late 19 c. Wayne County Republican politics. Others were among the Exodusters who left NC for Arkansas. Thanks, as always, for your beautiful work!

LikeLike

Thank you, Lisa. I think we have a Mutual Admiration Society going– you work is such a treasure and no one else is doing anything like it. Glad you enjoyed the story– and somehow I am not surprised that your ancestors were troublemakers in that neck of the woods– good for them!

LikeLike

Pingback: Adam Scott, Barbecue Artist, in Wilson. | Black Wide-Awake