This is the final photo-essay in my series “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.”

You can find my introduction to the series here.

This rather grainy photograph shows a portion of a sprawling migrant farmworkers camp that was located just outside Aurora, a small town on the North Carolina coast, in the 1940s.

The camp was built during the Second World War to house 500 to 600 migratory farm laborers and their children.

Located just south of the Pamlico River, Aurora in those days was a quiet little town with a population of only 300 or so most of the year. However, that changed dramatically every spring, when the migrant workers arrived to harvest the local potato crop.

A few days before harvest time, great crowds of men, women, and children arrived in Aurora and moved into this camp and a host of far more ramshackle tenant houses, tobacco barns, and tarpaper shacks that farmers more typically gave them for their quarters.

In the matter of a few days, the total population of the town doubled and then doubled again. By the time the last caravan of field workers arrived in Aurora, the local population had risen from 300 to somewhere in the neighborhood of 2,000 people– and all the newcomers were there to work in the potato fields.

-2-

This is another, also grainy view of the big migrant labor camp in Aurora. The photograph was taken in June of 1947.

Today the town of Aurora’s fame rests on being the site of one of the largest open pit phosphate mines in North America and on being home to the Aurora Fossil Museum, a lovely little museum that highlights the marine fossils that the mining company’s excavators dug out of the earth.

But that was not the case when these photographs were taken. The international mining conglomerate Texas Gulf Sulphur did not begin phosphate mining in Aurora until the mid-1960s.

Until that time, Aurora was known instead for digging a very different treasure out of the ground– white potatoes.

Beginning with the arrival of the first railroad in or about 1910, potato farming had boomed in Aurora.

By the 1930s, Aurora was the state’s largest potato market and local boosters often referred to the town as “The Potato Capital of the World.”

It was a somewhat overly enthusiastic claim perhaps, but one that gives an indication of the size and importance of potato farming both in Aurora and in much of the rest of Beaufort County as well.

During and just after the Second World War, Beaufort County’s farmers shipped out some 800,000 pounds of potatoes a year.

Across much of the North Carolina coast, the sandy loam soils east of U.S. Highway 17 were ideal for growing the spuds.

Beaufort County was the state’s largest producer of white potatoes (often called “Irish potatoes” in those days), but those potatoes were an important crop in a broad swath of tidewater counties.

At that time, the state’s other leading potato farming counties included Pamlico County, just down the road from Aurora; Tyrrell and Washington counties, on the south side of Albemarle Sound; and Pasquotank, Camden, and Currituck counties, on the north side of Albemarle Sound.

(Source: North Carolina Agricultural Statistics, 1944-1946 (Raleigh: N.C. Dept. of Agriculture No. 89: 1946.)

-3-

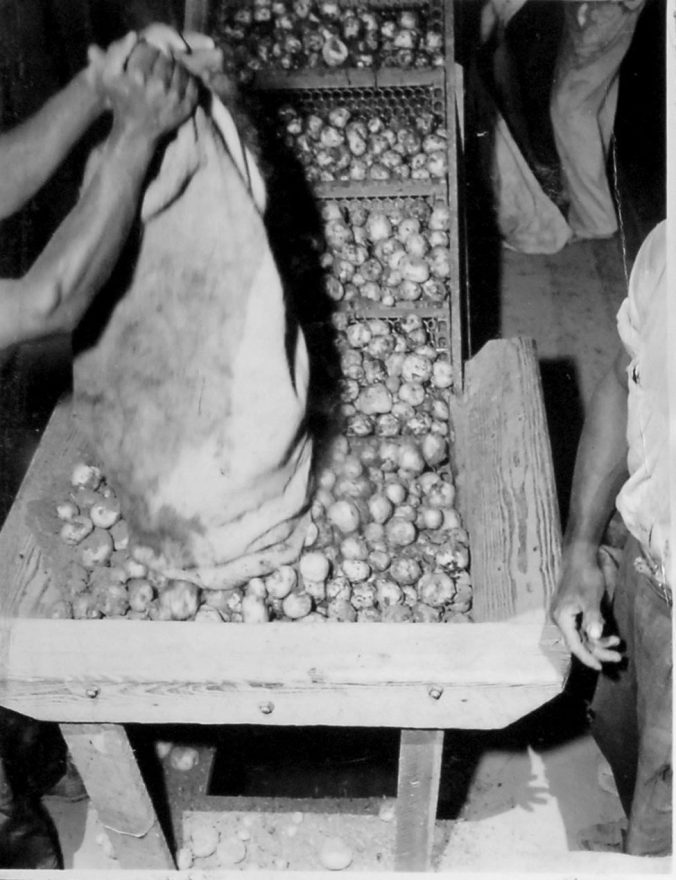

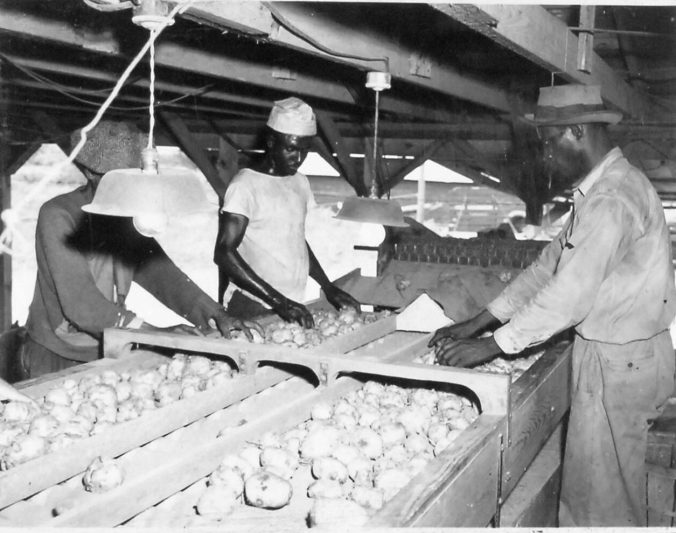

A scene from a potato packing house in Aurora, N.C., 1947. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Working through labor agents, Aurora’s farmers recruited most of their harvest workers in South Florida. They drew especially from the communities around the vast truck farming and citrus grove plantations in the vicinity of Lake Okeechobee and the Everglades.

At that time, most of the migrants were African Americans from the Deep South. Many were young single men, but many families were also part of what came to be called the “East Coast Migrant Stream.”

They came largely from tenant farms and plantations in Georgia, North Florida, Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi, and they had taken many different paths to the fields of South Florida.

In a way, they were refugees from lives arguably even harder, more dangerous, and more oppressive than that of migrant laborers.

During and just after World War II, a significant number of the migrant laborers in Aurora and across the East Coast migrant stream were also immigrants from American and British colonies in the West Indies.

Many of those people had first come to the U.S. as guest workers during the Second World War.

During the war, military planners had invited them to the U.S. as part of a national strategy to address a wartime shortage of agricultural labor. In many cases, federal and state agencies placed the workers with individual farmers who requested help at harvest time.

The wartime guest worker program had recruited thousands especially in Puerto Rico, Jamaica, Barbados, and the Bahamas. Under what was called the “Bracero Program,” the country’s wartime planners also recruited many temporary agricultural workers from Mexico.

-4-

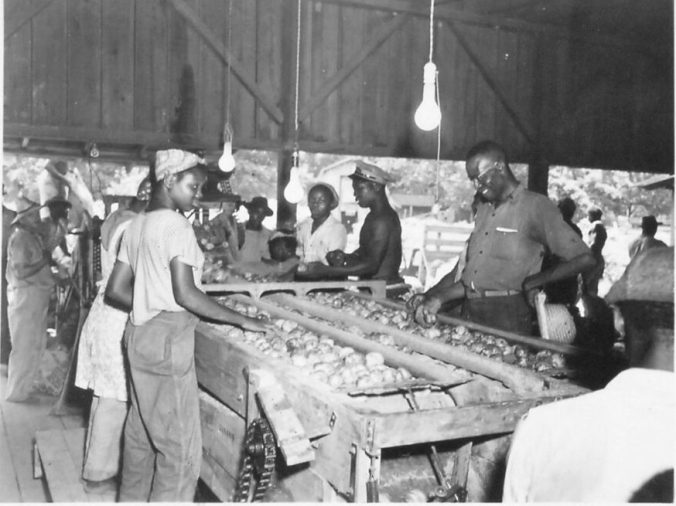

Grading potatoes in Aurora, N.C., June 1947. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

The migrant farmworker camp that we saw in our first two photographs was not at all typical of migrant housing elsewhere in Aurora or in other parts of Eastern North Carolina.

In the spring of 1942, a federal agency called the Farm Security Administration (FSA) had established that camp in Aurora to serve as model housing for “transient farm workers.”

Fearful that a wartime rural labor shortage would leave the local potato crops to rot in the fields, local farmers and state agricultural leaders had jointly petitioned the FSA to make Aurora one of the sites for a new kind of government-run camp for the nation’s migratory workers. (See the Washington Daily News, 5 April 1941.)

The FSA’s new camps were part of the national strategy to attract migratory labor to America’s fields– and by so doing, helping to assure adequate food production during the war.

At least as I understand them, the FSA camps in Aurora and elsewhere in the U.S. embodied a New Deal idealism and a belief in the dignity of the American worker that would soon seem very out of fashion, but which was still evident at least at the beginning of the war.

The advantage of the FSA camps to farmers like those in Aurora was incontestable, though the farmers’ motives may not always have been especially noble.

As historian Cindy Hahamovitch has noted in her landmark study of the history of the migrant stream on the East Coast, if the FSA camps had not been built, the wartime labor shortage might have given local fieldworkers greater leverage in their efforts to gain higher wages, better working conditions, and, for those who needed it, more decent housing.

The FSA had opened the East Coast’s first model migrant labor camp in Belle Glade, Florida, in the spring of 1940. That camp accommodated 600 workers, all white, who were hired to harvest truck vegetables near Lake Okeechobee.

The FSA opened a second camp in Belle Glade late in 1940 or early in 1941: it was reserved for Black and Latino workers. (Winston-Salem Sentinel, 17 April 1940.)

In all cases, the FSA’s labor camp program built migrant housing of a nature that had never been seen before in the rural South and to my knowledge has never been seen since the Second World War.

The camps were clean, sanitary, and well-maintained. They had laundry and cooking facilities. They had community centers. They had nurses and a property manager on site.

At least one source, the Durham Sun (29 Sept. 1942), in Durham, N.C., indicated that at least some of the FSA camps provided child care.

In Eastern North Carolina, the first FSA camps opened in the spring of 1942. By April 13, 1942, according to the Washington Daily News, the FSA was in the process of opening camps for potato harvest workers in Aurora and at three other sites on the North Carolina coast.

-5-

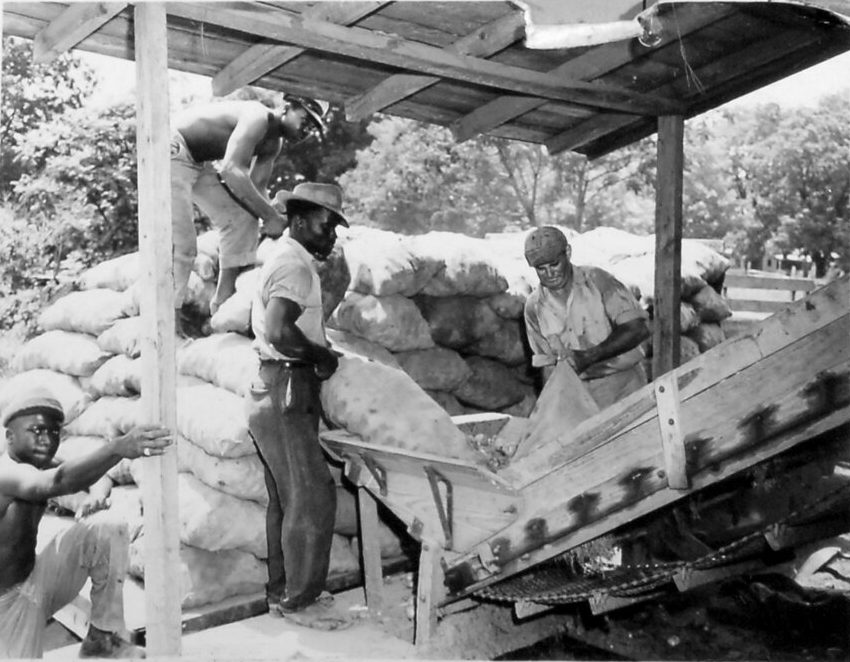

This is another view of migratory workers grading potatoes in Aurora, N.C., in June 1947.

The FSA built model migrant labor camps at a total of nine locales in North Carolina during World War II.

Four of those sites provided housing for potato harvest workers on the North Carolina coast. In addition to Aurora, those sites included Bayboro, in Pamlico County; Belcross, in Camden County; and Grandy, in Currituck County.

In the state’s southeast corner, three other FSA camps sheltered men, women, and children who harvested strawberries, lettuce, celery, and other truck crops. They were located in Chadbourn, in Bladen County; Castle Hayne, in New Hanover County; and Wallace, in Duplin County.

The FSA also built a camp for cotton and peanut workers in Enfield, in Halifax County, and another to house migrant laborers who harvested green beans near Henderson in Western North Carolina.

In the spring of 1943, yet another government labor camp for potato harvest workers opened in Travis, a rural coastal community five miles west of Columbia, in Tyrrell County.

The FSA was not involved in that camp however, and it seems to have been of a different and potentially more oppressive nature.

According to the Raleigh News & Observer (14 June 1943), Tyrrell County’s potato farmers had convinced county leaders to provide housing for 125 to 150 fieldworkers at the Travis School, a public grade school for African American children.

The News & Observer’s story indicated that the camp would have a manager similar to the FSA camps, but would also have “special police.” The story does not refer to the camp providing nursing, childcare, or any special standard of living or any of the other special facilities found at the FSA camps.

-6-

Here we see migrant laborers bagging potatoes at a packinghouse in Aurora, again in June 1947.

Five years earlier, on the 4th of June, 1942, the Richmond Times Dispatch provided a good description of the first FSA camps that were built in southeast Virginia and on the North Carolina coast:

“Each of the camps in the potato section [is] comprised of 75 tent shelters, with auxiliary tents. The tents are fitted over wooden platform floors. The auxiliary tents provide shower baths, laundry facilities, and a community gathering place for church services and other activities.”

The article goes on to say, “Each of the camps can at present accommodate 500 persons and sufficient additional equipment is on hand to double that capacity if needed.”

-7-

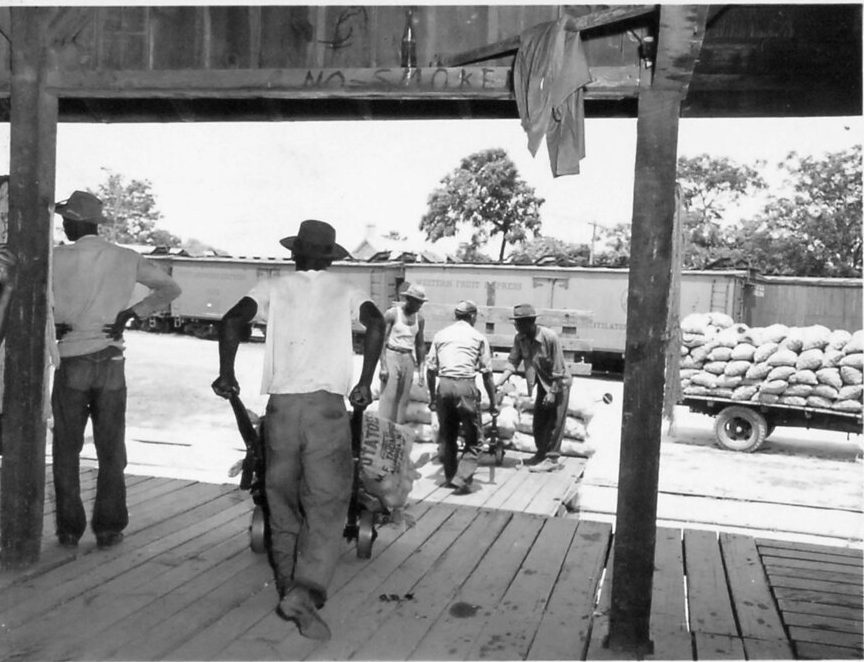

Here we see two men loading bags of potatoes onto a freight car at the railroad depot in Aurora.

After the end of the Second World War, the FSA continued to maintain the camp in Aurora for a year or two.

In the spring of 1946, the Washington Daily News reported that “migratory workers from Florida, about 1,500 strong, are expected to arrive [in Aurora] in groups ranging from 10 to 150″ beginning the 18th of May.

According to the newspaper, the FSA camp was expected to house 650 of those migrant laborers. Others found quarters on local farms– in abandoned shacks, in old tobacco barns, and anywhere else they could lay a pallet.

“Pay for these workers is expected to be about eight cents a bushel for work behind the digger, with variations for work behind a plow,” the Daily News noted.

Over the next year, the Federal Government took steps to get out of the labor camp business.

On December 8, 1947, the Daily News reported that 25 of Aurora’s potato farmers had banded together and purchased “the old FSA labor camp.” The farmers intended to continue to house migrant laborers there, but under private ownership, not the Federal Government’s.

As best I can tell, the human rights ideals of the New Deal did not figure into the farmers’ new plans for the camp. They did not take any special steps to assure the higher living standards for which the FSA strove early in the war, and they also did not provide child care, nursing, or other social services.

-8-

This is my final photograph in this photo-essay and also in this whole, 21-part series that I have been calling “Working Lives.”

The photograph shows a scene at a loading dock in Aurora. A group of men are moving bags of potatoes down to the edge of the dock. They will load them either onto the flatbed truck on the right or onto the train.

Whole trainloads of potatoes left Aurora every spring.

When their work was done, the potatoes harvested, and the last bag loaded onto the last freight car, the migrant laborers would leave the “old FSA camp” and all the other migrant quarters in the Aurora area.

They would continue north to where other farmers were waiting for them to harvest other crops.

For many, the next stop was the Eastern Shore of Maryland; for others, the truck farms of southern New Jersey.

I wonder what it was like to see them go, if you were a permanent resident of Aurora, I mean.

Maybe the town’s people feared them and called them names and took every opportunity to make them feel small and unwanted, like so many people treat refugees and immigrants in America today.

If so, the locals were probably glad to see them go.

Maybe people in Aurora even used words like “garbage” to describe the men and women who harvested their crops, as our president said of Somali immigrants and refugees night before last.

Maybe that is also the way it was in Aurora in 1947, but I hope not. I hope that the town’s people were better than that.

Maybe it was different then. Maybe the local people missed their help, and maybe they missed the friendships that had sometimes been made, despite all the differences between the locals and the migrants.

I even wonder if the departure of the harvest workers left the local people with a feeling of disquietude, or even a kind of loneliness, when they saw how empty and quiet the land was without them.

-End-

I loved this series. It was very interesting and I shared many of your articles. It is information only a historian would search out and share. This last installment is my favorite. Thank you for all your time to bring this i formation to us.

LikeLike

Thank you for this last report about the migrant workers in Aurora. I appreciate your comments about how cruelly migrants are being treated in our country today. It is shameful. They do the hard work no one else wants to do and suffer for it

LikeLike