I first listened to a special group of interviews with African American community elders in Pamlico County, N.C., almost 20 years ago, but I have never forgotten them. They helped me to see history as more than dates and wars, the rise and fall of the powerful, and the stuff of headlines.

They helped me to understand that history is all those things, but it is also the paths of our souls and the life of the spirit.

The oral history project was called “Preserving the African American Experience in Pamlico County, North Carolina.”

The project was led by Ms. Linda Simmons-Henry, a scholar, archivist, and public historian whom I have known and admired for many years.

Ms. Simmons-Henry was uniquely well prepared to lead the project. At that time, she was the director of special collections and the senior archivist at Saint Augustine’s College in Raleigh.

She is currently the dean of the library and archives at Texas College, an HBCU in Tyler, Texas.

She is also a native of New Bern and has always remained deeply attached to the African American community there and in Pamlico County, just to the east of New Bern.

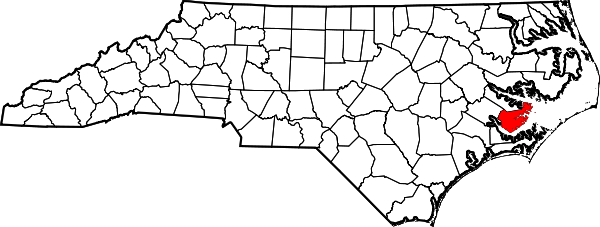

Pamlico County is a largely rural part of the North Carolina coast. The county borders the Pamlico Sound, the Neuse River, and the Pamlico River. Bayboro, the county seat, is 15 miles east of New Bern. Map courtesy of Wikipedia

Over the spring and summer of 2007, Ms. Simmons-Henry and a talented team of local volunteers conducted oral history interviews with 20 of Pamlico County’s African American elders.

I found the interviews to be a rare treasure. Taken together, they are a compelling and intimate portrait of African American life in Pamlico County over most of the 20th century.

The whole tenor of the interviews is special. When you listen to them, you can tell that the project’s volunteers and the elders were people who knew and cared for one another.

In the voices of the project’s volunteers, I heard respect and reverence for the elders whom they were interviewing. I also heard a yearning to learn from their wisdom and experience.

In the voices of the elders, I heard a special kind of care. They talk about history, but they also sound like wise grandparents gently sharing love and guidance with those of a younger generation whom they know will need all the help they can get in this fragile, broken world of ours.

* * *

I first listened to the interviews back in 2007. The project’s volunteers had organized a banquet to celebrate and honor the community elders who had so graciously shared their stories with them.

I had been invited to say a few words at that banquet. To help me to prepare for the occasion, Ms. Simmons-Henry made a copy of the interviews for me.

At that time, the project’s volunteers had not yet transcribed the audio tapes, so I could not read transcripts of them. In a way, it was nicer: it meant that I had to listen to them, which I did, and it was a delight.

It made me feel as if I was sitting down with the elders and listening to their stories along with the project’s volunteers.

The interviews and transcripts are now available both at the New Bern-Craven County Public Library in New Bern and in the Southern Oral History Program’s collection at the Southern Historical Collection at UNC-Chapel Hill.

* * *

The project’s oldest interviewee was a woman named Annie Rachel Squires. She was born in a little community called Maribel, on the Bay River, in 1908. At the time of her interview, she was 99 years old.

Ms. Squires and the other community elders shared stories about many different parts of Pamlico County’s history.

They talked about their teachers and schools. They spoke of childhood joys. They remembered long, brutally hard days of digging in potato fields and shucking oysters in the local canneries.

Pamlico County Training School, ca. 1918. Many of the elders who participated in the oral history project were alumni of the PCTS. Courtesy, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

“All I know about my life was work, work, work,” I remember one woman saying, I believe in Vandemere.

The community elders also recounted tales of the local struggle for voting rights and racial justice in Pamlico County.

Some remembered the landmark school desegregation lawsuit that black citizens in the coastal town of Oriental filed in 1951. Two or three recalled incidents involving the Ku Klux Klan.

Others told stories about serving in the Second World War and the Vietnam War. Yet others remembered the Great Depression.

My curiosity encompassed all of those historical subjects, but they are not what I remember most about the interviews.

What struck me most deeply about the elders’ words when I first listened to them back in 2007, and what I still find most unforgettable about them now, is how much they are a history of faith and the spirit.

* * *

For instance, I will never forget the project’s interview with the Rev. Kenneth M. Bell, Sr., who at that time was still the minister at the Green Hill Missionary Baptist Church in Bayboro.

He was the only church pastor whom the project’s volunteers interviewed, but when it came to matters of the spirit, his words were very similar to most of the other elderly men and women that were interviewed.

Like the Rev. Bell, they spoke of their faith and their struggles to know and understand God more fully.

They shared stories of Sunday schools and Bible study groups. They described a hunger to understand more fully what Scripture had to teach them about our purpose here on Earth, the nature of our existence, and what we are called to do for one another.

The Rev. Bell was interviewed by Ms. Sandra Mae Hawkins, one of the project’s most devoted volunteers. At one point in the interview, she asked the Rev. Bell what he considered the most important event in his life.

He did not hesitate for even a second.

He said it was the day in his boyhood that Mrs. N. F Harper sang “Pass Me Not O Gentle Savior” at Green Hill Missionary Baptist Church and he accepted Jesus Christ as his Lord and savior.

* * *

When Rev. Bell spoke of Mrs. Harper singing “Pass Me Not O Gentle Savior,” he was remembering a worship service 60 or 70 years earlier.

Born in Bayboro in 1941, he was the youngest of 12 children.

When Sandra Made Hawkins talked with him, he explained that he had grown up in hard times. However, he did not linger on his family’s hardships or the things they did without.

Instead, he talked about his father, who was a farmer and a devout member of the local AME Zion church.

His father was not the pastor of the church, but he had been a missionary: the Rev. Bell explained that when his father was not in his fields, he strove to live the Bible’s teachings.

He visited the sick, lonely, and down and out. He cut firewood for elderly neighbors. After hog killings, he shared the meat with those who had none.

In the interview, the Rev. Bell recalled that his father’s face had been disfigured in a hunting accident when he was a boy.

When I heard that part of his life story, I wondered if his father’s malformity had helped to teach him, and maybe his son too, to look at people’s souls, not on that which is only skin deep.

Rev. Bell remembered that people in Pamlico County often referred to his father as a prophet. He said that his father understood how to listen for God’s word, and again and again, God spoke to him. God made him promises, and those promises, the Rev. Bell said, came true.

He was not describing the world that we watch on TV or read about in the New York Times: he was describing a world where miracles happened.

“He never talked much to us except about the Bible,” the Rev. Bell recalled.

He spoke with great admiration and appreciation for his father. On the other hand, listening to his interview, I also got the feeling that he felt as if his father may have left some important things unsaid.

* * *

I was also taken with the project’s interview with a gentleman named Charlie Styron. Mr. Styron was born in Oriental in 1933.

I wish I had known him. He spoke with a beautiful voice, full of kindness.

In reflecting on his life, Mr. Styron described how he had always worked with his hands. Listening to him talk about his life, I got the impression that there was not much that he could not do with those hands.

For many years, he had worked at a sawmill and a veneer plant. But at different times, he explained, he had also made his living as a heavy equipment operator, a bricklayer, a carpenter, and an electrician.

After he retired, he said, he found his greatest joy in playing with his grandchildren. He kept active, too. At the time of the interview, he was still operating a lawn mower repair business out of his home.

Passers-by often saw him singing hymns and praying while he worked on the lawnmowers.

Sandra Mae Hawkins was also the project interviewer who spoke with Mr. Styron.

When she asked him, “What have been some important events of your life?” he, like the Rev. Bell, did not hesitate even for a moment: “Well, to be born from above, that was the most important event,” he told her.

* * *

The project’s interview with a woman named Eula Felton Monk also stood out to me. Ms. Monk had grown up in Mesic, a rural, predominantly African American community on the Bay River.

I had a good friend there when I was young, Ed Credle, who was Mesic’s first mayor. Listening to Ms. Monk’s stories gave me a special joy because they brought back memories of Ed and his neighbors whom I got to know in Mesic back in those days– good people, all.

When Ms. Monk was a girl, she recounted, her father had been the captain of a shrimp trawler. He worked on the Bay River and out in Pamlico Sound, but he also followed the shrimp as far south as Key West.

At the time of her interview, Mrs. Monk had been a teacher for 43 years. She had retired from full-time teaching, but she was still working part-time as a substitute teacher in the local public schools.

When asked about her childhood, she recalled long days of working in the fields: chopping cotton, digging potatoes, picking tobacco.

Her family worked on local farms, but also traveled to fields as far away as Merritt, Arapahoe, and Aurora.

She spoke of her schoolteachers with great reverence. She had endless admiration for how they did so much, and cared so much for their students, back in those days of Jim Crow when Pamlico County’s schools were segregated by race and so little was given to the African American schools.

Mrs. Monk said that she would never forget the great debt that she owed those teachers.

When the interviewer asked her if she was religious, she, too, was matter of fact:

“I believe in God and I believe in being a doer of His word…, [and I] try very hard to do those things daily that He says that I should do in His world.”

The interviewer then asked a question with a kind of directness with respect to faith and religion that I do not often see in oral history projects.

She asked if Mrs. Monk believed in Jesus Christ.

Mrs. Monk was not caught off guard by the question in the least, and her reply was direct:

“Oh, yes I do, as my Lord and my Savior. He is my Savior. Yes.”

When the interviewer asked her how she put her faith into action in her daily life– another question I do not often hear in oral history interviews– Mrs. Monk turned to Scripture:

“Second Timothy 2:15 says to study to show thyself approved of God, not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth. I study the word of God, and then I pray.”

She also said:

“And the Bible says we should visit the sick…, the Bible says that we should reach out to those who are less fortunate than we are… and to love thy neighbor as thyself.”

She said that she strove to do all those things, though of course she acknowledged that she was far from perfect.

Then she said:

“I love God with all my heart and all my mind, and all my soul. And I would like to say, the greatest point in my life, the most important event in my life, is when I accepted Jesus as my Lord and Savior, when I became saved.”

* * *

As I listened to their voices, I found a comforting sense of familiarity in the way that the lives of the Pamlico County elders were entwined so tightly and so seamlessly with their faith and their churches.

I grew up just across the river from Pamlico County, and I found that their voices reminded me again and again of home and the lives of my family and the people around whom I was raised.

* * *

There was a kind of cadence to the stories of their lives, like a gentle heartbeat, held steady by their knowledge of themselves as spiritual beings and kept in time by daily prayer, Bible study, worship services, Sunday school, church suppers, choir practices, baptism, weddings, and funerals.

So many little things in these interviews caught my attention, and they did so in a way that, even all these years later, they remained fixed in my memory.

Listening to the interview with Annie Squires– the 99-year-old woman I mentioned earlier– I could feel how her heart filled with joy when she played the piano at her church in Maribel.

She told the young woman who interviewed her that she had been the church’s pianist for more than half a century.

Children jumping rope at the Pamlico County Training School, ca. 1918. Courtesy, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

Likewise, in my mind’s eye, I could see Roosevelt Stokes, Jr., another of the interviewees, as he made his weekly rounds among the frail and sick in Grantsboro’s nursing home.

He had never been a pastor or a missionary at a church, but he had his own ministry visiting those people who lived in the nursing home.

On the days of his nursing home visits, Mr. Stokes would stop and read the Bible to any of the patients who desired him to do so.

He would hold their hand, and often they would pray together. Sometimes one of the nursing home’s CNAs would join them.

His words brought back memories for me, and maybe helped me appreciate what it was like for Mr. Stokes to read the Bible by those bedsides, and how much it might have meant to those who lay there– because, now and then, I have been called on to read the Bible at a bedside, too.

* * *

I know these are just little moments, but even some of the passing comments in the interviews made a deep impression on me.

For instance, another of the interviewees, Emma Bell, recalled how, when she was a small child, her mother began every day by giving a Bible verse to her and to each of her brothers and sisters.

They would read the Bible passage at breakfast.

I could see them: a mother and her children, early in the mornings of what I am sure were busy days, taking a few minutes to recite Bible verses before going out into this stormy world of ours.

I also loved a little something that one of the other interviewees, Sabia Ruth Gibbs, said.

Ms. Gibbs grew up in Maribel. Way up in her 90s, she was one of the oldest people who shared her life story with the project’s volunteers.

All the same, when she was asked to pause for a moment and think about the long span of her life, one of the first things she did was reach far back in time, as if to another world, and describe the joy of singing in the choir at St. Galilee Missionary Baptist Church when she was a girl.

She remembered it like it was yesterday.

It was a memory, in her telling of it, that seemed to be made of pure light.

* * *

I doubt that I am much different from anyone else. When I am driving through the countryside, as I did last night, on my way to my family’s homeplace on NC 101, I go by all the homes and see the lights on and I wonder how the people that live there are doing, and do they feel loved, and, if they pray, what they pray for at night before they fall asleep.

I wonder about their prayers, and all that goes unsaid in life, and the whispered words we have between us and our maker.

At those times, I think about the quiet joys for which we show gratitude at that late night hour. I think too of the fears that go unsaid everywhere else, the dreams that we keep to ourselves, the hungers that can’t be put into words.

The interviews in “Preserving the African American Experience in Pamlico County, North Carolina” are an invaluable historical record of life on the North Carolina coast throughout the 20th century.

The more times that passes, the more special they will seem, the more important they will be.

I cherish them for that reason but also because they help me to remember that our path through life– our history– is partly what can be seen and heard and touched, and partly what cannot.

Merry Christmas. Happy Hanukkah. Seasons Greetings.

To one and all.

Thanks, and merry Christmas.

LikeLike

This is truly lovely. Thank you for this and your other fine postings. Balm in a bad time.

❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️

Catherine Bishir

>

LikeLike

Thank you, David, for the time, labor, and love you invested in weaving together the words and memories of the elders in Pamlico County, NC, who were interviewed 20 years ago. I am very grateful that you invited us to listen with you to the spiritual wisdom of these elders that touched you deeply 20 years ago and still moves you today. In this time ~ when cruelty, violence, and injustice seem to have the upper hand ~ I draw heart and hope hearing the testimonies of the love, faith, and joy that grounded these elders in Pamlico County, and gave them the strength to carry on.With abundant gratitude,Melanie Morrison

LikeLike

Very moving. Thank you.

LikeLike

Fanny Crosby was probably the favorite hymnwriter of the great-grandmother who lived two doors from me and Pass Me Not with sung by a quartet at her funeral. I love the hymn too and am now wishing wishing I could have heard Mrs. Harper’s version. I will be reading every word of these interviews, David, and I so agree with the post Melanie M. left here. To do the work which is needed we will all need the strength of what has always been described to me (by friends of both races) as the Black church abd Black community. And I don’t think we have much time.

LikeLike

P.S. Apologies for all my typos. I’ll be fine soon as I find my readers. Happy, warm holidays to David and all.

LikeLike