Workers digging tulip bulbs on the Van Dorp family’s flower farm in Terra Ceia, N.C., 1941. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

In May of 1938, a young woman named Muriel L. Wolff spent several weeks interviewing people in Terra Ceia, a community of Dutch immigrants, African Americans, and other settlers who had all come to that part of the North Carolina coast to try to make a new home in hard times.

When she went to Terra Ceia, Wolff was working for the Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal program that employed writers who were struggling during the Great Depression. Some wrote guidebooks; others, like Wolff, documented American life and history.

Wolff talked with all kinds of people while she was in Terra Ceia. She then came back to her home in Chapel Hill and wrote a chronicle of her time there and what she had learned.

In that account, Wolff also included at least partial transcripts of the interviews that she had conducted in Terra Ceia.

Some time ago, I found the original copy of Muriel Wolff’s writings on Terra Ceia in the Federal Writers’ Project Papers at the Southern Historical Collection at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Terra Ceia is located in Beaufort County, N.C., approximately 20 miles northeast of Little Washington. Map courtesy, Wikipedia

Wolff opened her report with these words:

“About twelve miles from the blue waters of the Pamlico Sound in Beaufort County there lies an area of drained swamp land, so rich that it was once given the name ‘Heavenly Earth’ although the people who live there facetiously call the region `The Dismal.’

“Oddly enough, both names fit because it is a community of sharp contrasts.

“There are comfortable, well-built houses with all conveniences and there are miserable little shacks that seem to be falling apart; there are big dairy farms with 60, 70, or a 100 cows, but many families do not possess even one; on the vast, black fields, thousands of bushels of potatoes and corn, grain and beans are grown, yet laborers steal because they are hungry.”

That was during the last years of the Great Depression, but I guess some things have not changed: that seems very much like the world in which I grew up, and also very much like the world in which we live now.

-2-

When Muriel Wolff went to Terra Ceia, she was still quite young. She was born in Concord, N.C., between Greensboro and Charlotte, in 1910, so she was only 28 years old at the time.

Her passion was for the theater. She began her acting career at Women’s College (now the University of North Carolina-Greensboro), where she appeared in student productions between 1926 and 1928.

After leaving Women’s College, she studied at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts in New York City. She then came back south and join the Carolina Playmakers, the well-known repertory company based at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

She toured with the Playmakers from 1929 to 1931. At that time, the troupe was writing, producing, and performing plays set in some of North Carolina’s most hardscrabble communities– the state’s cotton mill villages, its tobacco farming hamlets, its mountain hollows.

One of Wolff’s most memorable roles was the lead in the original cast of “Strike Song,” a play that was set against the backdrop of a textile workers’ strike in the Carolina Piedmont.

In “Strike Song,” Wollf played “Lily May Brothers,” the most dynamic and inspiring of the strike’s leaders.

Her character was modeled after Ella May Wiggins, a 29-year-old mother, songwriter, and labor activist who was murdered in retaliation for her union activism in Gastonia, N.C., in September 1929.

A scene from the original production of “Strike Song,” a 3-act play written by James and Loretto Bailey for the Carolina Playmakers, ca. 1930-31. Muriel Wolff was the lead actress in the play and I am fairly confident, but not 100% sure, that the actress in the photograph’s center is her. I did not find any other photographs of Ms. Wolff. Photo courtesy, UNC Libraries

Sometime in 1931, Wolff evidently found that she could not make a living with the Playmakers and took a job as secretary to William T. Couch, the director of the University of North Carolina Press.

However, she continued to moonlight with the Playmakers and to act in local experimental theater for most of the 1930s.

Her work with Couch led to her job with the Federal Writers’ Project. In 1938, in addition to his job at UNC Press, Couch was also serving as the southern director of the Federal Writers’ Project.

In that capacity, Couch employed Muriel Wolff to conduct a series of oral history interviews in Terra Ceia.

In all likelihood, he had first heard of Terra Ceia through several recent magazine and newspaper stories that had featured the community’s Dutch immigrants and their flower farms.

In the 1930s, when other cash crops seemed lacking, a number of Dutch immigrants in Terra Ceia had turned to growing flowers on a commercial scale.

Before long, the sight of their broad fields of tulips, iris, and daffodils began to attract crowds of visitors to the little community in the spring.

-3-

Terra Ceia’s roots reached back to the late 1800s and early 1900s, when the Roper Lumber Company and the Norfolk & Southern Railroad worked hand in hand to clearcut and drain hundreds of thousands of acres of virgin swamp forest on that part of the North Carolina coast.

A pair of brothers, John A. and Samuel Wilkinson, were the driving force behind the founding of Terra Ceia.

They were farmers in a little crossroads community called Wilkinson (named, of course, after their family), a few miles east of Terra Ceia. They bought thousands of acres of cutover land from the Roper Lumber Co. and drained and burnt off what was left of the swamp forest.

Once the forest was gone, the Wilkinson brothers marketed the reclaimed swampland to farmers. They took special pains to recruit white Midwesterners, many of them immigrants.

Soon after arriving in Terra Ceia, Wolff and a young local woman, Margaret Respess, rode horseback out to Wilkinson to visit Sam Wilkinson, the only one of the brothers who still lived in the area. He was farming on the land where he and his brother had grown up.

The little settlement was not much more than Sam Wilkinson’s house, broad plains of farmland, a crowd of shacks where farmworkers lived, and a general farm supply and grocery store owned by the Wilkinson family.

-4-

Sitting down with Muriel Wolff in the store, Sam Wilkinson told her about the birth of Terra Ceia.

He told her:

“When I was a boy all that land over there wasn’t anything but swamp. It was full of great big cypress and juniper trees timber that never had been cut. Well, back in 1905, I was working for the Roper Lumber Company, located over in Belhaven, and they started logging that swamp.

“To do that, they had to dig ditches and drain off some of the water, but it still wasn’t fit for anything when me and my brother bought up 20,000 acres in 1911.

“The first thing ever put in that land was stick corn—you know what that is, don’t you? You just stick a hole in the ground, drop in a grain of corn and cover it up. That corn was put in before the stumps were cleared or the land really drained, but it produced between 15 and 20 bushels an acre.

African American workers planting “stick corn” at or near Terra Ceia, ca. 1910. In July 1918, a journal called Cut-Over Lands (vol. 1, #4) described how the Wilkinson brothers used the planting of stick corn at two locales near the Pungo River– Potter Farms and Terra Ceia– as the final step in converting the swamp forest into agricultural fields.

“That’s when the stories got started about how rich the land was over there.

“If you don’t believe we spent the money, I’ll tell you what we had to do. That was swamp land, remember, and ditches wouldn’t drain off all the water. There had to be 40 miles of canals besides the ditches.

“We paid $20,000 for a dredge to dig canals. It broke after the first seven miles. We bought another but it broke too before we finished.

This is one of the Wilkinson brothers’ dredges at work in the swamp forests at or near Terra Ceia, ca. 1918. Source: Cut-Over Lands vol. 1, #4 (July 1918).

“Then we had to put through a branch line of the railroad—11 miles of it at $1,000 a mile. Before we could lay a track, we had to buy the right of way and buy $70,000 worth of Norfolk & Southern stock. But we got the railroad through. There it is today.

This is a log train traveling on the Norfolk & Southern’s main line bound for the John H. Roper Lumber Co.’s mill in Belhaven, N.C., ca. 1907. The railroad that Sam Wilkinson was describing was an east-west spur of this line. Source: American Lumberman, April 27, 1907.

“Our original plan was to get the land in a good state for cultivation, divide it into 50-acre plots and make it available to poor people and give them a long time to pay for it. We might have been able to do this, if we hadn’t had some more bad luck.

“My brother and I both had stock in the Roper Lumber Company, and it burned without being covered with a cent of insurance.

“Another trouble was land fires. A lot of that land over at Terra Ceia is peat soil and once it gets on fire you can’t hardly put it out. When you do get it to stop smoldering, it’s been ruined.

“All the reverses we had made it impossible for us to carry out our plan. We didn’t have any capital left…. There’s been a sight of money spent on Terra Ceia, and there was a time when money was made there, when land that first sold for $15 to $20 an acre brought $200 to $300 an acre.”

Wilkinson made clear that those days were long gone. “Well, we got experience, but it cost us mighty high,” Wolff quoted him.

He then walked out of the store and across the yard to his house to have his dinner before he headed back into the fields.

-5-

On another morning, a local farm woman named Odell Snows took Wolff to visit a Mrs. Tantrelle in Terra Ceia. Tantrelle was the wife of an Italian immigrant who managed a large farm for a group of northern investors. Wolff was taking room and board with the Snows family.

“It was mid-morning when we started out in the new Plymouth,” Wolff wrote.

“The Snows live in a small settlement which might be called the center of Terra Ceia. Here is the only store run by a white in the community, here the Christian church and the Dutch church which was once the schoolhouse.

“We drove down the dusty road. On one side of it a few scattered houses stood in bare dirt on the edge of the fields; along the other side ran the canal and the railroad track, beyond which were fields.

“Odell drove slowly and explained the landscape. `Negro tenants live in that house, and there too. Yes, most of them are Negroes, except in that place. They’re some white tenants of Mr. Radcliffe’s.

“`An Italian man lives in the place there by that big barn. They say he can write music and poetry and play any kind of instrument.

“`See how far down from the road this land is? I can remember when it was almost level with the road, but it’ s burned down that far.’”

Another view of workers on the Van Dorp family’s flower farm in Tera Ceia, 1941. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

She was referring to the effects of peat fires on the landscape in Terra Ceia. In some places, the layer of peat beneath the swamp forest had been 10 and 12 feet deep, so that when it burned off it left the roads far higher than the surrounding fields and pastures.

In her report, Wolff continued to quote Odell Snows.

“`Now down here is the land owned by that Winston-Salem man who doesn’t do no farming at all. He just ships the dirt. His overseer has a gang of Negro men working most all the time, digging up the dirt, packing it in bags and loading it on that freight car that stands over on the siding.’”

“`When they have a carload [of the peat soil],’” Wolff continued, still quoting Odell Snow, “`the train will come through and pick it up. They say he gets a good price from people who buy the soil to put on their lawns and gardens. It’s so rich I guess it takes the place of fertilizer.’”

She went on:

“When we had come about a mile down the road from Odell’s, we crossed the canal to turn into the road where the Tantrelles lived. Built by a Northern company many years before, this little settlement had an overgrown, uncared for look which was still somehow picturesque.

“About a dozen steep-roofed cottages were spaced along both sides of a shady road and a canal bordered with sycamore trees. We left the car in the road and reached the Tantrelle’s house by way of a bridge that arched over the canal where several ducks were swimming.”

-6-

The settlers in Terra Ceia had taken many different paths to that part of the North Carolina coast.

As Wolff went about doing her interviews for the Federal Writers’ Project, she found that many of the black families in Terra Ceia had come from the east side of the Pungo River, in Hyde County.

Terra Ceia, 1941. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

They were largely the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of African Americans who had been enslaved laborers along the shores of the Pamlico Sound before the Civil War.

While in Terra Ceia, Wolff also met people—white people— from Appalachia and others from as far away as Iowa, Kansas, and Michigan. At least a couple were Italian immigrants. More were Dutch immigrants.

In her report, Wolff described meeting a husband and wife from Mt. Airy, N.C., in the Appalachian foothills. She met another couple from near Bryson City, N.C., in the heart of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Still another couple had come all the way from Kansas City.

Yet another husband and wife that she met were Dutch immigrants who had first settled in the Midwest.

Things had not worked out for them there, so they had left and moved a thousand miles east to the North Carolina coast, not to Terra Ceia at first, but to a farm colony called New Holland.

New Holland was located on the southern shore of Lake Mattamuskeet, 45 miles east of Terra Ceia. It had not lasted long. The colony’s fate had depended on a grand scheme to drain the lake and turn it into farmland, but the lake had turned out not to be so easy to do away with.

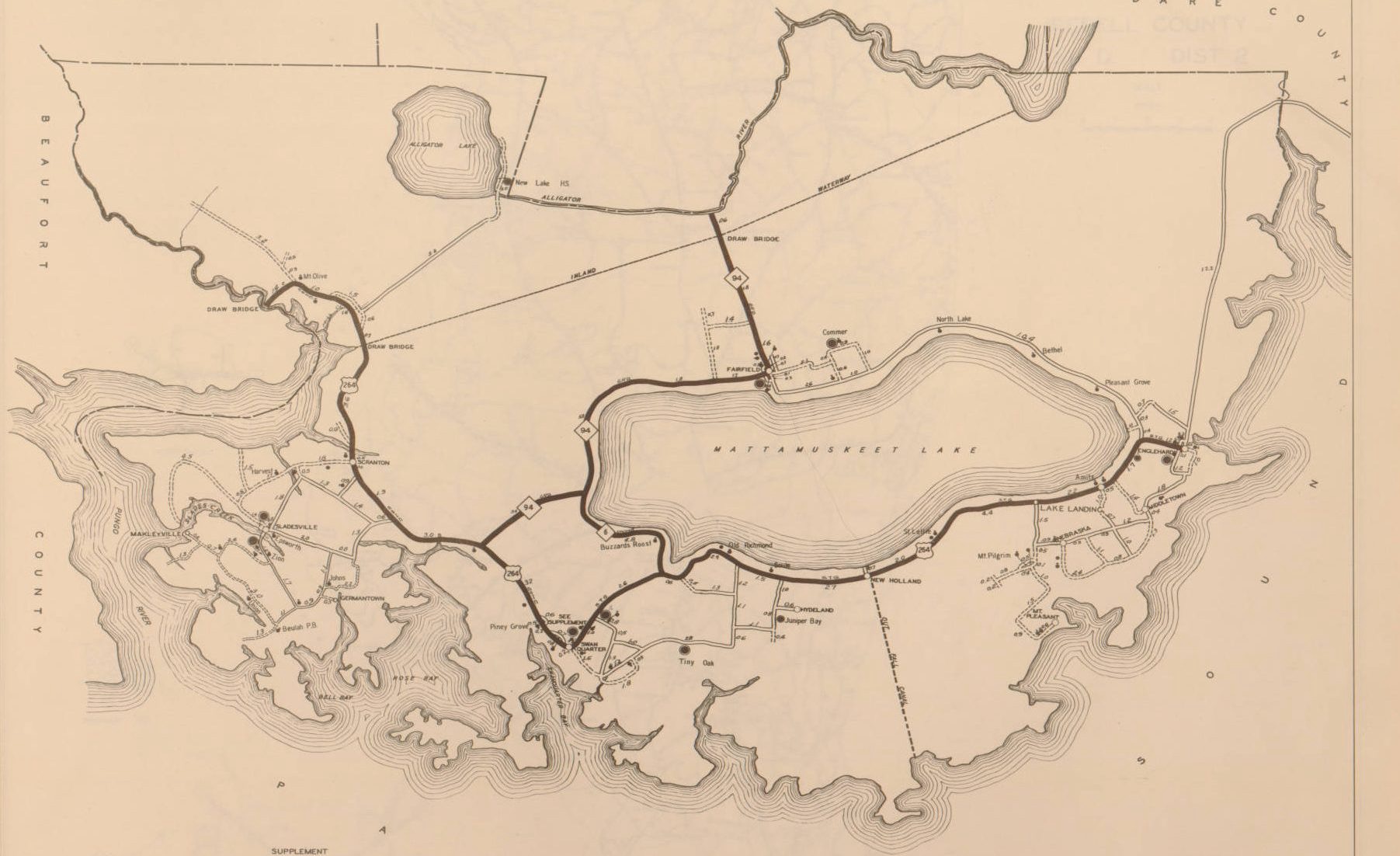

This is a 1936 road map for Hyde County, N.C., just east of Terra Ceia. Lake Mattamuskeet occupies the map’s center-right section. A few years before this map was drawn, the lake had reclaimed its bottom and nearly all of New Holland– a hotel, train depot, store, warehouses, barns, cottages, etc.– had been flooded and abandoned. On this map, the remnants of New Holland are still indicated as being on the lake’s south shore. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Like countless others trying to find a home in the 1930s, when so many lives were tossed and turned about, the Dutch family pulled up roots again. They left New Holland and put their hopes for a new life in Terra Ceia.

The Great Depression had been hard on all of those people. All of them were trying to make a new beginning.

-7-

I found Muriel Wolff to be at her best as a writer when she was chronicling small moments. She often recalled even the briefest encounters with a kind of grace and beauty that made them memorable.

One of those was a visit with an African American woman named Sarah Lovett.

Sarah Lovett and her husband, the Rev. James “Jim” Lovett, lived in White Six, a settlement of mainly African American families on the eastern side of Terra Ceia, on the old dirt road that led to Pantego.

In the Fall 2010 issue of the Beaufort County Community College’s wonderful oral history journal, Life on the Pamlico, one of the college’s students quoted her mother, saying: “We lived in an area known as White Six. It was given that name because it was a predominantly black neighborhood, but there were six white families that live on farms in the area.”

Most of the black residents of White Six worked in the local flower fields as often as they could get work in them.

The Lovetts were both from Hyde County, but had moved to White Six when times had gotten hard on that side of the Pungo River.

When they first arrived in White Six, the Rev. Lovett had made a decent living as a barber, which I imagine he did in addition to working in the fields. That was before the Great Depression, and he and Sarah had even been able to save up enough money to buy a bit of farmland.

In addition to barbering and working in the fields, James Lovett was the minister at one of the two African American churches in White Six.

Wolff wrote:

“On one of his plots of black earth, Jim Lovett built a small white house and Sarah… coaxed thin little borders of verbena, roses, and privet to grow along the edges of the bare front yard.

“It was in this yard that Sarah stood with me one fresh May morning, while three small boys and one girl looked up at us with solemn black eyes.”

“Sarah’s voice was as soft and charming as her personality,” Wolff wrote.

“She had a way of cocking her head to one side and squinting at the sky as she talked.”

The Depression Years—and a late freeze that spring—had been devastating to the people in White Six, Sarah Lovett told Wolff.

“`I work in the field by the day, when I can get it. Everybody was mighty hurt this year when the flower crop froze. It knocked so many out of work—especially the women folks. Out here in White Six, where most of them work by the day, it’s been a hard spring.’”

Sarah Lovett continued, “`Two of these little children I’m keeping today belong to a neighbor of mine who’s been sitting at home worrying for a month because there wasn’t nothing for her to do. Today she got a job digging iris. That will bring her a dollar for every day she works.'”

Sarah Lovett told Wolff that, unlike some other settlements around Terra Ceia, at least most of her neighbors in White Six could put food on the table for their children, even if it wasn’t always much.

She said, “`It’s a good thing so many of the White Six people own their own houses and enough ground to have a garden, some chickens, and hogs. They manage to raise most of what they have to eat, anyway.’”

I could almost see the two women there in Sarah Lovett’s kitchen, the humble cottages of White Six all around them, the endless fields, the great labyrinth of canals leading down into the sea.

There, with the sunlight coming in the window, they talked about life and told stories and held one another up a bit, as people do.

That is all I wanted from becoming a historian: to be able to listen to voices like theirs, and the more of them the better, a gentle murmur rising all around us, like some great tenderness in the dark.

This looks fabulous. I am fixing to read her writin’ but wanted to say thanks right away. The reference to white midwestern farm folks (of course) reminds me of a story you may know already but in any case is outside your “zone.” The Ridgeway Company was formed right after the Civil War by some Warren County planter folks (Hawkins etc.) and some carpetbaggers (J. M. Heck) to attract (white) German families to settle and farm land near the Raleigh and Gaston RR (town of Ridgeway became the center). Their descendants stayed. When I was doing architectural survey work in Warren County in the 1970s (halcyon times), I knew nothing of that story but began to notice the anomalous tidiness of the agricultural landscape and some biggish barns. What can this be? says I. This is not your usual Warren etc. County farm landscape. We drove a little farther. Voila! A Lutheran church well kept (of course) and obviously in loving use. Intuition confirmed, now find out the story, which I began to do. At that time, as I recall, some of the older community members still spoke German (as well as English), and kept in touch with kinfolk back home. I think they were told that their German accents pinpointed their region of origin. One can look up the Ridgeway Company, I imagine, but I’d be pleasantly surprised if anyone did an oral history there as was done in Terra Ceia. Your fan always. C Catherine W. Bishir cate902@yahoo.comCary NC919-377-0020 h919-744-7746 c

LikeLike

Just found this from Googling. Article in Warrenton paper My thanks to Barbara Sinn Bumbalough and her outstanding book, “Come With Me To Germantown Ridgeway, North Carolina Revisited,” for the information for today’s story. So, if you will join me on a short trip on US 1 South we’ll turn back the clock to the 1870s and see our forebears’ vision for Ridgeway.

Catherine W. Bishir cate902@yahoo.comCary NC919-377-0020 h919-744-7746 c

LikeLike

After having read many of your posts, and all of this one, I am especially—profoundly—moved by the last paragraph. Thank so much.

LikeLike