View of Ocracoke Lighthouse and Silver Lake, Ocracoke, N.C. Courtesy, Wikicommons

“This used to be an island where the men went to sea.” That’s what 95-year-old Blanche Howard Jolliff told me a few years ago, when I visited her on Ocracoke Island, one of North Carolina’s Outer Banks. I was the guest of her cousin Philip and his family next door, and Philip took me by to see her.

Philip Howard is the owner of one of the island’s oldest and most beloved businesses, The Village Craftsmen. He’s also a first-rate local historian. You can find his very interesting blog, called Ocracoke Island Journal, here.

Philip Howard, the owner, and his daughter Amy Howard, the manager, at the Village Craftsmen, Ocracoke, N.C. Specializing in fine quality American handcrafts, the shop is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. Photo courtesy of Philip Howard and the Village Craftsmen

At supper the night before, Philip had told me about a strong historical connection that once existed between his remote island home and Philadelphia, the great seaport 400 miles north on the Delaware River.

I’ve long been interested in the ties that have historically bound North Carolina’s coastal towns and villages to maritime communities in distant parts of the U.S. and in foreign lands.

I’ve written about some of those ties, such as the ones that menhaden fishermen forged between Beaufort (N.C.) and maritime communities as far north as Tiverton, Rhode Island, and as far south as Moss Point, Mississippi, over the last 150 years. (You can find one of those articles here.)

But I have been visiting Ocracoke Island all my life and I had never heard anything about the island’s historic relationship with Philadelphia.

Yet Philip made clear to me that night that the ties that bind Philly and Ocracoke are old, profound and fascinating.

When I told him how interested I was in those ties, Philip suggested that we talk with his cousin Blanche to learn more.

A Morning on Howard Street

The next day Philip and I visited his cousin. Blanche passed away last year, but at that time she was still flourishing and lived in one of the oldest homes in the village.

The village of Ocracoke is home to a year-round population of 900 people, and a multitude of visitors join them in the summer. The village sits at the southwestern end of Ocracoke Island, a 14-mile-long, windswept and very beautiful wisp of sand located 25 miles out in the sea.

Blanche Howard Jolliff, Ocracoke, N.C., 2015. Photo by Peter Vankevich. From Philip Howard’s Ocracoke Island Journal

Two ferries connect the island to the mainland, and both take more than two hours to make the journey across the sound. Another, shorter ferry runs to and from Hatteras Island, one of the other Outer Banks.

When Philip and I called on Blanche, she graciously welcomed us into her home, which was one of the island’s last houses that still had an old-fashioned “summer kitchen” separate from the main house.

Like Philip’s house and The Village Craftsmen, Blanche’s house was also located on one of the village’s last unpaved roads. Shaded by live oaks and myrtle bushes, the sand road is dotted with family burial plots.

Blanche was a very gracious hostess, and she had an extraordinary knowledge of the island’s history. Spending a morning with her was a delight.

She and Philip and I talked a long time, though eventually Philip had to leave us on our own so he could get to his shop.

The Sea in Their Blood

“Water was what they grew up on and it was all they knew,” Blanche told me. She was referring to the old Ocracokers, the elderly people whom she had known as a child and their ancestors.

“They had the sea in their blood, because that’s the way they came up,” Blanche said again.

But, she cautioned me, that did not mean they only knew Ocracoke Island and were not familiar with the ways of the world.

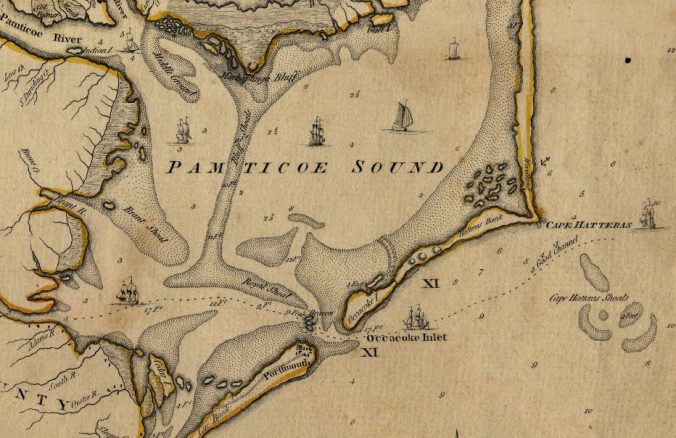

Ocracoke and vicinity, ca. 1775. Detail from Henry Mouzon and others, “An Accurate Map of North and South Carolina With Their Indian Frontiers….” Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

The first generations of Ocracokers had been ship pilots and the families of ship pilots, she said. The earliest English maps of Ocracoke Island, in fact, referred to the village as “Pilot Town.”

Many of the island’s men in those days also went to sea, especially when they were young. They’d join the crew of a ship passing through the inlet and were sometimes gone for years.

Even then, the island was remote, but not provincial: those Ocracoke seamen came home with stories from all over the Atlantic. Some returned with wives or consorts from distant parts, too.

The village was a long way from anywhere. But sitting on their front porches, the islanders shared tales of Baltimore, New York City and Philadelphia, and also of Port-au-Prince, San Juan and Marseilles.

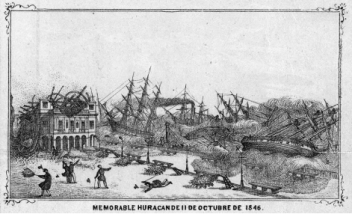

The 1846 Havana Hurricane

Blanche and Philip told me that a hurricane in 1846 was one of the great turning points in the island’s history. Ocracoke Inlet had been shoaling up and it had gotten more difficult and more dangerous for ships to make the passage in and out of the Pamlico Sound.

The 1846 hurricane was one of the hemisphere’s most powerful tropical storms in the 19th century. The storm devastated communities and transformed whole ecosystems on the N.C. coast, but the worst damage and loss of life was in Cuba. From “Mapa Historico Pintoresco Moderno de la Isla de Cuba” (Hamburg: 1853).

Then the 1846 storm broke open two new passages through the Outer Banks. Less than 20 miles to the north, the hurricane opened Hatteras Inlet and, farther north, Oregon Inlet.

In the Caribbean and South Florida, that hurricane is known as the 1846 Havana hurricane, because of the destruction it wrought in Cuba. On some other parts of the East Coast of the U.S., it is remembered as the Great Gale of 1846.

After the hurricane, Ocracoke Inlet was no longer the only or the best passage for seagoing ships in and out of the Pamlico Sound. The masters of vessels began sailing instead to those more northern inlets.

That was the end of piloting on Ocracoke. Some of the village’s men moved to Hatteras so they could keep piloting, but more of them, with no other way to make a living, went to sea.

Blanche showed me a copy of the island’s listing in the 1850 U.S. Census. By that time, Ocracoke had scarcely any pilots at all, and only 2 fishermen, but 22 seamen made their homes there.

Boomtowns & Lumber Schooners

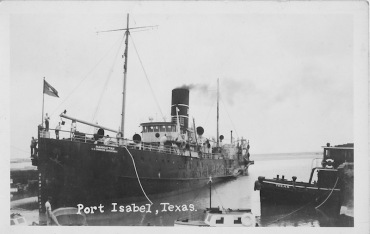

Philip and Blanche told me that Ocracoke’s special relationship with Philadelphia started with those sailors. At first, the village’s native sons worked on the sailing ships that carried lumber from North Carolina to Philadelphia and other seaports on the Delaware River.

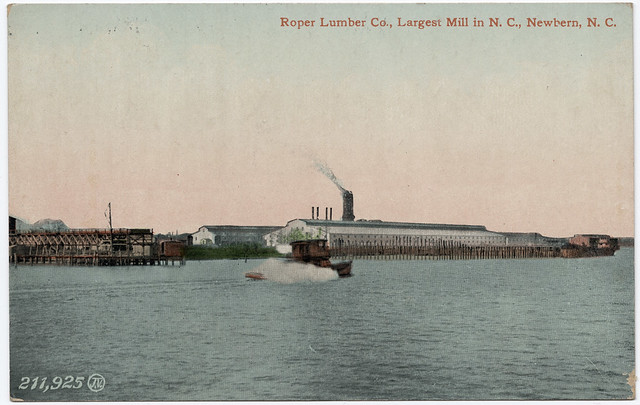

The lumber trade was a big business on the North Carolina coast in those days. After the Civil War, northern lumber companies purchased hundreds of thousands of acres of forestland across the state’s coastal plain.

Most of those companies came from Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York. We still find evidence of them in the names of coastal communities such as Scranton, in Hyde County, which is named after the Scranton Lumber Co. of Scranton, Penn.

We also see evidence of them in the names of coastal towns such as Roper, in Washington County. The town’s name comes from the John L. Roper Lumber Co., whose founder, John L. Roper, was a native of Mifflin County, Penn.

Postcard of the Roper Lumber Co.’s mill, New Bern, N.C., ca. 1910. Many of the lumber schooners that passed through Ocracoke Inlet were bound for New Bern. The company had other mills on the N.C. coast as well, including its big cedar mill in Roper, in Washington County. Courtesy, N.C. Collection, Wilson Special Collections Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

The lumber companies built mills in larger coastal towns such as New Bern, Washington and Elizabeth City, but they also established dozens of mills and company towns in remote swamps and other out-of-the-way places.

The once great forests of the Mid-Atlantic States and New England had largely been exhausted, and the lumber companies’ appetite for “North Carolina yellow pine” seemed limitless.

The construction, furniture, shipbuilding and other industries of the northern states also sought out white cedar, cypress and other hardwoods that could be found in the state’s coastal lowlands.

Workers moved in, boomtowns rose up, railroads were built. They lasted as long as the timber did.

Over half a century, nearly all of the coastal plain’s old-growth forests disappeared. In time, the mills closed, the towns vanished, the railroad track was torn up.

That happened again and again and again—all over the North Carolina coast. For generations, that was a way of life. During those decades, the lumber business was a bigger part of the state’s coastal economy than commercial fishing or anything else.

Much of that lumber left North Carolina on the railroads. However, much of the lumber also traveled out of the state in the holds of big, broad-beamed, fore-and-aft-rigged sailing vessels called schooners.

The 5-masted lumber schooner Governor Ames. On a voyage from Brunswick, Ga., to New York City in 1909, she wrecked off Cape Hatteras, all hands but one lost. From classicsailboats.org

Many of those lumber schooners had sailed for Philadelphia.

To emphasize that point, Philip took out a ledger that one of his Ocracoke ancestors had kept.

The ledger listed the names of ships that had wrecked on Ocracoke Island, as well as their destinations and what freight the vessels carried.

A striking number of the wrecked ships had been carrying lumber, and a striking number had been bound for Philadelphia.

And, as Philip and Blanche Howard taught me, many of those schooners had sailors from Ocracoke standing on their decks or perched high in their rigging as they sailed toward the City of Brotherly Love.

Perry Howard and the End of the Age of Sail

According to Blanche, the first Ocracoke sailor to go to Philadelphia and stay was her uncle, Perry Howard. He had sailed aboard a schooner into Philadelphia sometime around 1900.

While Perry Howard was in Philly, he apparently realized that the schooner trade was coming to an end. The Age of Sail itself was on the wane, and he knew it: he could see that for most kinds of domestic commerce, the railroads, not ships, were the nation’s future.

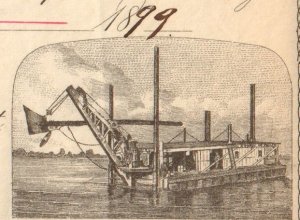

Perry Howard bid his mates good-bye and got a job with the American Dredging Company. Founded in Philadelphia in 1867, the company was one of the largest river and harbor dredging companies in the U.S.

Detail of an American Dredging Co. stock certificate showing a dredge boat at work, 1899.

The company’s dredge boats built harbors, deepened and widened river and canal channels, removed obstructions, drove bridge pilings and did a host of other jobs up and down the Delaware River.

Perry Howard was 18 years old at the time. He rose quickly up the ranks and was soon captain of a dredge. It was said at the time that he was the youngest captain on the river.

“There wasn’t any work here”

Perry Howard was one of three brothers that left Ocracoke and moved to Philadelphia in the early 1900s.

Their decisions to leave the island reflected hard economic reality. “There wasn’t any work here,” plain and simple, Philip explained.

A host of other Ocracokers followed in Perry Howard’s footsteps. Philip’s father, Lawton Howard, was among them. He left Ocracoke in 1927, when he was 16 years old. He had a 6th grade education and a fiddle.

Philip’s dad Lawton Howard (left), playing banjo at an Ocracoke variety show with Jule Garrish (guitar) and Edgar Howard (banjo). In 1977, their music was part of a Smithsonian Folkways album called Between the Sound and the Sea: Music of the North Carolina Outer Banks. Photo from Philip’s Ocracoke Island Journal

I love how Philip described his dad’s arrival in Philly on his Ocracoke Island Journal blog:

With the exception of one overnight boat trip to Hatteras with a fishing party, Lawton had never been off the island. He was soon overwhelmed in the city. He had never seen a train, a brick building, an indoor toilet, running water, or electricity.

In his Spartan hotel room he noticed a wall socket (the light bulb had been removed). Curious, he stuck his finger in the opening!

Back home Lawton’s mother had taught her young son good manners. Whenever he passed neighbors on the sandy lane, or sitting on their porch, he was instructed to greet them politely.

On his first jaunt down Philadelphia’s busy Broad Street he said he nearly wore himself out saying hello to everyone he passed.

Lawton Howard got his first job on a hopper dredge for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. He started as a deckhand, but he was a welder with the Corps for most of his career.

Philip recalled that his father came home with holes in his shirt from the sparks of his welder.

You can read Philip’s lovely tribute to his father here.

“In the cold-raw days of February”

Philip’s uncle Marvin Howard also moved to Philly. A legendary figure among the country’s dredge boat captains, he worked mainly on the Delaware River. However, he also took his dredge to jobs on the Mississippi River and other waterways across the Eastern U.S.

In the late 1930s and 1940s, Marvin Howard was master of the sea-going hydraulic hopper dredge Manhattan. He was based on the East Coast, but at one point he took the boat to Galveston, Texas, to dredge the port. Photo courtesy, Ocracoke Island Journal

In an article that he wrote decades later, and which Philip quotes in a tribute to his uncle that appeared in Ocracoke Island Journal, Marvin Howard described what it was like to leave Ocracoke in the 1910s.

At that time, many of the island men who went north came home to the island in the winter.

Here’s how Marvin Howard remembered those times:

I can think of nothing during my 37 years away from my home of Ocracoke more pathetic . . . than when, as a boy, sharing with many others the fate of leaving Home. [I saw] the young men and old alike, each spring, start their migration northward, [to try to] find a job.

[They would leave] their families, each with their luggage, and very few dollars in their pickets, walk down the sandy roads, before dawn, in the cold raw days of February and March, when the light of cottages from early risers shined bright and clear, down to the fishing wharves, where the daily mail boat left at 4 A.M.

These men were going off! Away—to the far north . . . to look for work, going where it was even colder than home, where if a job was found, they would remain for about 8 or 9 months, or until cold fall when the icy blasts froze up the rivers of the great industrial north, or fishing, on account of winter winds and cold, ceased along the Atlantic Seaboard.

During the Second World War, Marvin Howard even dredged abroad. Early in the war, he led a four-ship convoy of dredgers to England in order to deepen the channel on the Thames River.

Capt. Marvin Howard. From Philip’s Ocracoke Island Journal

Three more of Philip’s uncles also moved to Philadelphia or other ports on the Delaware River and worked on the water.

One, Enoch Howard, was a tugboat captain. He settled in Elsmere, Delaware, which is on the Christina River, a tributary of the Delaware.

Another uncle, Evans Howard, died of pneumonia on a dredge boat in January of 1923. He was 17 years old at the time.

Naked Ladies & Dancing Camels

The youngest of Philip’s uncles, Homer Howard, also left the island and moved to Philadelphia.

Philip remembers him fondly as a romantic and exciting character, and perhaps as a bit of an endearing ne’er-do-well.

Born in 1914, Homer served in the U.S. Navy as well as in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. He had tattoos of naked ladies on his legs and Philip remembers that he could flex his muscles and make his tattoos “dance.”

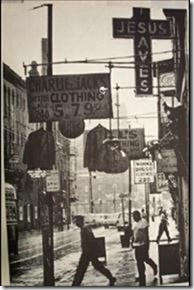

Philly’s Skid Row ran from East & Vine to 6th. Full of flop houses, missions and cubicle hotels, drug dens and brothels, it was a place for transients and the down and out and a place where you could find the worst of humanity and sometimes the best, too. Photo, Jay Gertzman

One of Philip’s young cousins used to make paper dolls and dress up Homer’s tattoos.

Homer was apparently too rambunctious to stay very long on the dredge boats. He drank quite a bit and had a wild streak a mile wide, and he soon fell on hard times. He lived at least briefly on Skid Row in South Philly and did all kinds of jobs.

Philip recalls that one of the more interesting was at a circus, where Homer beat the drum for a dancing camel.

Homer Howard spent his last days in Philly. At his funeral, young Philip marveled at the exotic-seeming women in fish net stockings that mourned for his uncle, as well as at a throng of neighborhood kids who came to see him off.

Philadelphia Bound

Philip’s father and uncles were far from being the only Ocracokers that moved to Philadelphia in the early 20thcentury.

In fact, when I visited her on Ocracoke, Blanche rattled off a long list of other islanders that worked on dredge boats, tugboats or pilot boats in Philly or elsewhere on the Delaware River early in the 20th century.

Her list included William Ballance, George Bennett, Hatton Howard, Nacie Williams, Neafie Scarborough, Alton Scarborough, Owen Gaskill, Clinton Gaskill, Julius Bryant, Charlie Morris O’Neal, Lafayette Howard, and Billy Howard and his children.

The Ocracoke Midgette brothers, Philadelphia, ca. 1985. Standing left to right: Carnelle, Elmer Gray, John (“Johnny Boy”), Ellis and Jesse. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers recognized the brothers for their combined 129 years of service. Photo from Joyce Spencer, their sister, and shared with me by Philip Howard

Some others I knew of: my closest friend on Ocracoke, Alton Ballance, for instance, has often told me how his father worked on dredge boats in Philly.

Alton’s father, Lawrence Ballance, worked for the Army Corps of Engineers for 35 years. In his dining room, Alton still has a chair from his dad’s dredge.

A Dredge Boat Christmas

Alton’s classic account of island life, Ocracokers, includes an unforgettable story about spending a Christmas on his father’s hopper dredge. The dredge was based in Philadelphia but had been working on the Hudson River and was tied up in New York City over the holidays.

The story highlights the different ways that Ocracokers felt about their island home and their new lives after going north.

In the last pages of Ocracokers, Alton writes:

A skeleton crew was keeping watch over the vessel. One of these men was Joffrie Bryant, who had grown up on Ocracoke as part of the island’s only black family. His sisters and brother, Mildred, Musa, and Julius Bryant, were still living there.

Sitting in my father’s cabin that first evening of my visit, with the sounds of the Hudson River lapping the vessel and continuous clangings throughout the whole ship, Joffre, my father, and I talked about home.

“I haven’t been home in twenty years,” said Joffre. “I do miss it occasionally. I fished, crabbed, and oystered like the rest when I was there. I also worked in one of the stores on the island and ran on a freight boat to Washington.

” I never did want to go back. You stay away so long that you tend to forget it. You get adjusted to a different way of life. I don’t know most of the people there now.”

Although my father offered on many occasions to take Joffre home with him, he never accepted. My father came home as often as he could, sometimes driving the eleven-hour trip from New York just for a weekend with us.

On my last day in New York, my father and I were standing on the deck of the Staten Island Ferry, looking over at Manhattan, saying little but obviously thinking of home. Finally he said, “I wouldn’t trade Ocracoke for all of it, money and all.”

Working on the Delaware River

Many other Ocracokers also had strong ties to Philadelphia. Legendary local historian Earl O’Neal, Jr., who died on Ocracoke just last year, was another of them. He grew up in Philly.

He was the son of Earl Williams O’Neal, a rigger’s helper in the Philadelphia Navy Yard, and a mother that was a Prussian immigrant.

Blanche felt sure that there were other Ocracoke boys that went to Philadelphia that she just couldn’t recall offhand.

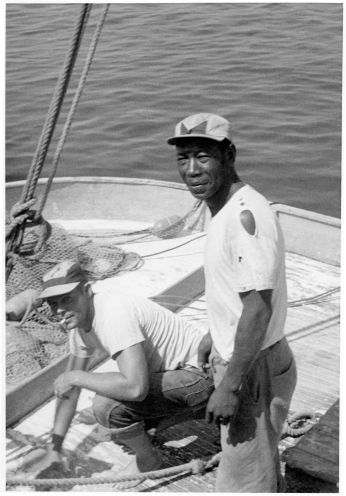

Julius Bryant, Joffrie’s brother, also worked in Philadelphia for a time, but he returned to a fisherman’s life on Ocracoke. Photo courtesy, Ocracoke Preservation Society

I got the same feeling the rest of my time on Ocracoke: I always got my morning coffee at a little store on Hwy. 12 where many of the island’s commercial fishermen hung out before going to the docks.

While I drank my coffee, I always asked the guys if their fathers or grandfathers had worked in Philly: the answer always seemed to be yes.

I bet 9 out of 10 of the guys I met at those morning coffee breaks said their fathers or their grandfathers had worked on dredge boats, tugboats or pilot boats on the Delaware River.

More recently, Philip has compiled a list of nearly 50 Ocracokers who moved to Philadelphia to find jobs. Most worked for the Army Corps of Engineers.

“Old Drum! Old Drum!”

Blanche told me that she had once heard a funny story about the large number of Ocracokers in Philadelphia.

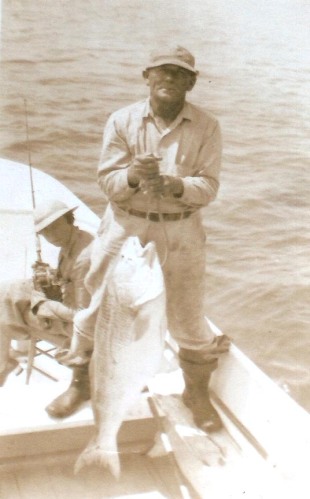

To appreciate the story, you need to know that “old drum” is the Outer Banks name for a fish called a red drum. Or more exactly, it’s the name for one of the big 20 pound-plus specimens of that fish.

Slow-cooked with onions, potatoes, a little salt pork and good bit of black pepper, a big, straight-out-of-the-ocean “old drum” is considered an unparalleled delicacy on Ocracoke Island.

It’s just the kind of dish that an Ocracoke mother might prepare for a son or daughter on their first night home from college, the military or the dredge boats on the Delaware River.

According to Blanche, the Ocracokers in Philly had a special fondness for the bars along Delaware Avenue. So, she told me, an old saying was that if somebody ran down Delaware Avenue yelling “Old drum! Old drum!” a crowd would have poured into the street!

Delaware Avenue, Philadelphia, with Delaware River and Benjamin Franklin Bridge in the background, early 20th century. Courtesy, kienantimberlake.org

Blanche’s little story spoke to the abundance of Ocracokers in Philly. It spoke to their affection for old drum. And of course it also spoke to how much many of them missed their island home.

“Families without a father”

For three generations, Ocracoke and Philadelphia were bound together. Some of the local men left the village and never looked back, but to varying degrees, most kept a foot in both worlds.

Many lived and worked in Philadelphia or elsewhere on the Delaware River for decades, but their wives and children stayed on Ocracoke.

Blanche’s father was one of those men. His name was Stacy Howard, and he got a job on a dredge boat on the Delaware River around 1900, when he was 18 years old.

Stacy Howard, Ocracoke, N.C. From Philip’s Ocracoke Island Journal

He came home long enough to marry Blanche’s mother, and the newlyweds first lived together in an apartment in Camden, Delaware, where Stacy had a job on a dredger.

When they began to have a family, Blanche’s mother moved home and she and eventually their son and four daughters remained on Ocracoke for the rest of Stacy’s dredging career.

Her mother cared for the children and saw them through school, raised them in the church and gave them the benefit of growing up around their grandparents and a big extended family.

She gave them a sense of place and belonging. She couldn’t, of course, be everything to them. As Blanche told me, having so many Ocracoke men work in Philadelphia had a cost.

Most importantly, she said, it “left families without a father.”

Her father came home when he could, but it wasn’t easy for him. When he did make it though, he always brought special gifts. And when he couldn’t make it, he mailed Victrola records and other presents to Blanche and the rest of the family that they could never have found on the island.

“Everybody . . . worked on the Goethals”

For most of his career up north, Stacy Howard was a lever man on a pipeline dredge in the Philadelphia District of the Army Corps of Engineers.

Blanche recalled that her father worked at one time on the Goethals, a big, oceangoing hopper dredge that operated out of Philly. The Goethals was a massive boat— more than 470 feet long and with a crew of 100.

”Practically everybody has worked on the Goethals,” Blanche told me. She meant, of course, every man on Ocracoke.

The hopper dredge Goethals in the Cape Cod Canal, in southern Massachusetts, date unknown. Many of the dredge men that were either unmarried or had left their wives and children in Ocracoke lived on the Goethals for years. Courtesy, dredgepoint.org

Making the journey from Philly to Ocracoke wasn’t as easy in those days as it is now, however.

“They didn’t come home much,” Blanche remembered.

To get home, her father had to take at least two trains. That was before the first private ferries to Ocracoke operated, and long before the state ferries began to run to the Outer Banks, so he also had to wait for the mail boat or a freight boat to carry him across the sound.

Phillip grew up in Philadelphia a generation after Blanche’s father worked there. Even all those decades later, the journey from Philly to Ocracoke took three days by car.

“A magical place”

Other Ocracokers lived in Philadelphia and raised their families there. Sometimes they married women from home and the couple lived together in the city or one of its suburbs, instead of the wives and children staying on the island.

Other times the men met and married their wives in Philly and stayed there to raise their families.

In those cases, most visited the island when they could: for a summer vacation, sometimes for Christmas and far too often for funerals.

Philip’s father, Lawton Howard, met Philip’s mother in Philly. Her name was Kunigunde (Connie) Guth, and she was the daughter of German-Hungarian immigrants. Together they made their home and raised Philip and his brother there.

When Philip was a boy, his family visited Ocracoke every summer. That was in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Philip remembers those trips fondly: the endless highways and the little country roads, the boat trip to the island and, after arriving on the island, the drive down the beach in his father’s ’48 Plymouth, since Hwy. 12 hadn’t been paved yet.

On those trips to Ocracoke, Philip and his family stayed at his grandparents’ house, where he lives now. To him, as a child, Ocracoke seemed like a different world, full of fantastical happenings and extraordinary wonders that he never saw in Philadelphia.

He remembers the pony pennings, when the island’s wild ponies were herded into the village for sorting and sales.

He remembers swimming in the creek, eating old drum and how most of the boys rode ponies in the village.

He’d take off his shoes when he arrived on the island, and he wouldn’t put them back on until he got back to Philadelphia.

“It was like a magical place for a young boy,” he told me.

Remembering my friend Alton’s story about Joffrie Bryant, I know some Ocracokers put the island behind them and never looked back when they took jobs in Philly or somewhere else up north.

But Philip’s father wasn’t among them. He lived in Philadelphia for 35 years, but he always considered Ocracoke home.

Philip told me: “My dad never talked about coming back to North Carolina or Ocracoke. He talked about coming home.“

A New Day

Lawton Howard did come home eventually. As did many other Ocracokers that moved to Philly, he and his family returned to the island after he retired from the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Phillip’s uncle Marvin, the legendary dredge boat captain, came home as well. He is often remembered today for starting Ocracoke’s famous mounted Boy Scout troop in the 1950s.

Marvin Howard first organized Mounted Boy Scout Troop 290 in 1954. Courtesy, Alice K. Rondthaler Collection, Ocracoke Preservation Society

In the 1960s, more of Ocracoke’s young people started staying home, too, instead of moving up north. Philip wasn’t sure, but he believed that a fellow named Stanley Gaskill was the last islander that went to Philadelphia to work for the Army Corps of Engineers.

By then the state ferries, the completion of Hwy. 12 and the rise of the tourism industry had brought new economic opportunities and made it possible for more Ocracokers to stay home.

“My dad’s generation”

During my visit, Philip and Blanche told me that they believed the island’s longstanding ties to Philadelphia had shaped Ocracoke in some important ways.

A Tastykake delivery van on Chestnut St., Philadelphia. From Wikicommons

They weren’t just referring to a lingering fondness for hoagies and Tastykakes either (though that, too).

Philip, in particular, observed that, generally speaking, Ocracokers had historically been more open to strangers and newcomers than people in some of the other remote island communities on the Outer Banks.

“My dad’s generation was more accepting and open to people from outside,” he told me.

I discussed Philip’s observation with several other friends and acquaintances on the island.

They tended to agree with Philip. They thought that openness also extended to immigrants (including the large number of Mexican immigrants living on Ocracoke today), as well as to differences amongst themselves, such as differences of race, sexual orientation and gender expression.

The Festival Latino de Ocracoke on the Ocracoke school grounds in the fall of 2016. It is now an annual event. Photo courtesy, Ocracoke Observer

Philip’s Ocracoke Island Journal has a story about an Ocracoker named Charles (Vera) Williams, born in 1898 and outwardly a female until the age of 21, and then a man the rest of her/his life, that I think also speaks to the island’s ways.

The Ties that Bind

I will be returning to Ocracoke again soon and I plan to think about these things more while I’m there. I’m looking forward to visiting with Philip again, too, though his sandy lane through the live oaks and gravestones won’t seem the same without Blanche there.

Blanche Howard Jolliff in her younger days. Photo courtesy, Ocracoke Preservation Society

But I already have a lot to think about. For now I wonder particularly if we can really trace the island’s spirit of openness and inclusion to its historical links to Philadelphia.

I’m not sure, but it does make me think. Maybe the bond between Ocracoke and Philly did shape the island in ways that I would never have guessed or suspected.

If that is right, I’m sure that we must also see the island’s ties to that great seaport as part of a continuous history of being connected by the sea to distant lands and far-off peoples.

There has, after all, never been a time when Ocracoke was really isolated or cut-off from the rest of the world, though that is a myth I have often heard. (See, for instance, a recent BBC story here.)

The truth, in fact, is just the opposite: for 400 years, the sea had bound the islanders to all the places, across all the oceans, from which people have come and found their way to Ocracoke, as well as to all the places that its native sons and daughters have wandered.

I cannot thank Blanche and Philip enough, or my friend Alton either, for helping me to see their island home’s history more deeply.

When I next step off the Ocracoke ferry, I will not forget what they taught me.

They showed me that we are all bound to distant shores. They helped me to see that the ties that bind us, one to another, have no limits. And finally they revealed to me how the heart of their island home, much like our own hearts, is as deep and fathomless and as full of wonders as the sea.

* * *

Special thanks to Philip Howard and his family for their hospitality while I was on Ocracoke and for all their help with my research. Thanks also to Alton Ballance for all his assistance and to the Ocracoke Observer and the Ocracoke Preservation Society for the use of their wonderful photographs.

ForGot all the USCoast Guard people. !! Horace Webb, Cwo4 Uscg Retired @ 31yrs.

Sent from my iPa

>

LikeLike

Totally agree! that’s another important story! Very different! I’d love to learn more about that story, too.

LikeLike

I love reading the history behind Ocracoke! Unfortunately, the recent hurricane, Dorian really hit hard there and I believe the main road in is still flooded or being worked on. I’ll be in Hatteras this weekend, so maybe that will tell.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve been coming to the Island since I was 9 yrs old with my Mom, Dad And Brother.. Alot of great Memories there.

I am now 48, going to visit the Mayans Take my Mother with me. Sure wish Dad was still here..

We stayed at many different places on the Island, mostly rented cabins from Zora Gaskins on the sound side.

A few times we stayed with a relative and her Friend Lilly Howard, on Howard Street, big white house..

My hand prints are still by the road where a guy was pouring a little concrete..

Can’t wait to come back, wish I could move there for good…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Going to visit in May.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: ocracoke and the philadelphia connection | Hidden Outer Banks

Pingback: The Whitehurst Fishery: A Down East Community on Lake Erie | David Cecelski

My grandfather, William Arthur O’Neal, was another Ocracoke native who left the island, settled in Wilmington DE and worked the tug boats on the Delaware River.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow, this article really opened my eyes to the hidden connections between Ocracoke and Philadelphia! I can’t believe I’ve been visiting Ocracoke Island my whole life and never knew about the historic bond with Philly. The quote from 95-year-old Blanche Howard Jolliff about the island being a place where men went to sea adds such a personal touch. It’s amazing to hear about Philip Howard’s family, especially owning The Village Craftsmen for 50 years – that’s impressive! I’m curious to know more about the details of the historical connection between these two places. Did anyone else from Ocracoke Island have stories to share about their ties with Philadelphia? 🏝️🌊

LikeLike