Freight cars waiting to be loaded with potatoes, Camden, N.C., 1940. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

This is a revised version of a photoessay that I published here a couple years ago, based on new findings at the Library of Congress.

I discovered another forgotten chapter in eastern North Carolina’s history while I was exploring the Farm Security Administration (FSA)’s photographs at the Library of Congress— it is a story about the migrant farm workers that harvested the region’s crops in the 1930s and ’40s.

Near Shawboro, N.C., 1940. Having finished the potato harvest, this group of Florida laborers was bound for New Jersey. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

An FSA photographer named Jack Delano took the photographs that caught my eye. He’s the same photographer that took the photographs of the migrant construction workers at Fort Bragg that I discussed here last week.

Farm workers eating supper on the front porch of the company store in Belcross, N.C., 1940. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

A talented photographer and composer, Delano was a Ukrainian Jewish immigrant who had come to the U.S. with his family in 1923, when he was nine years old. All of his photographs show a warmth and sympathy for others and a special concern for the down and out.

A farm worker from Texas at the potato grading station in Belcross, N.C. He was making 20 cents at hour. According to Jack Delano, the man dreamed of having his own sweet potato farm one day. Courtesy, Library of Congress

He was one of an extraordinary group of photographers that worked for the FSA during the Great Depression and the Second World War. They included figures such as Dorothy Lange, Gordon Parks and Marion Post Walcott that are now icons in the history of documentary photography.

Waiting for the foreman to show up, Belcross, N.C., 1940. Delano indicated that they were being paid a dollar a day. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Delano took the photographs of migrant construction workers at Fort Bragg in March of 1941. But nine months earlier, when the FSA was still focused on the economic turmoil of the Great Depression, he had spent time with other migrant workers in a different part of eastern North Carolina.

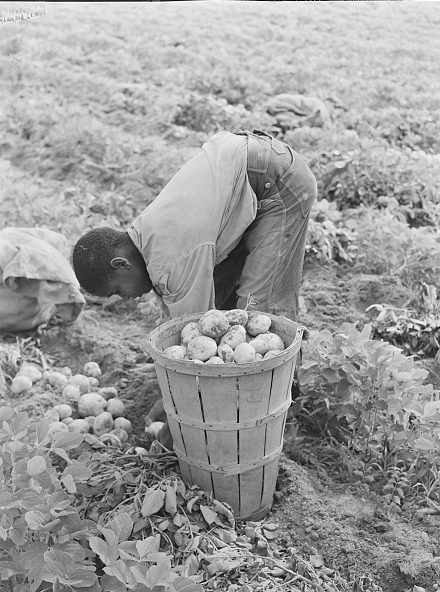

A young migrant laborer picking potatoes at T. C. Sawyer’s farm in Belcross, N.C., 1940. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Migrant farm worker near Belcross, N.C., 1940. Delano did not mention her name or anything about her, only that she was from Florida. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

In the summer of 1940, he took a remarkable series of photographs of the migrant laborers that harvested and packed potatoes in a group of counties not far from the Outer Banks.

Sacks of potatoes at freight station, Camden, N.C., 1940. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Traveling up and down the East Coast, those men, women and children worked in orchards and fields from Florida to New Jersey.

Outdoor kitchen for a labor camp in Old Trap, N.C. Approx. 35 men and women stayed at the camp during the potato harvest. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

In the wintertime, most worked in the citrus groves and vegetable fields of South Florida. They lived in sprawling camps of laborers in places such as Belle Meade, Immokalee and Homestead.

Migrant farm laborer in Belcross, N.C., 1940. She may be in her traveling clothes or headed to church; Delano did note that it was a Sunday. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

When they finished the harvest in Florida, they worked their way up the East Coast. The farm laborers in Delano’s photographs harvested potatoes here in North Carolina in June and July, then headed to jobs further north. Delano reported that they traveled next to Onley, a village on the Eastern Shore of Virginia, and to Cranbury, a small town in southern New Jersey.

Night shift at the potato grading station in Camden, N.C., 1940. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

That summer of 1940 Delano photographed migrant farm workers in Shawboro in Currituck County, N.C., and in Camden, Belcross, Shiloh, and Old Trap a few miles away in Camden County, N.C.

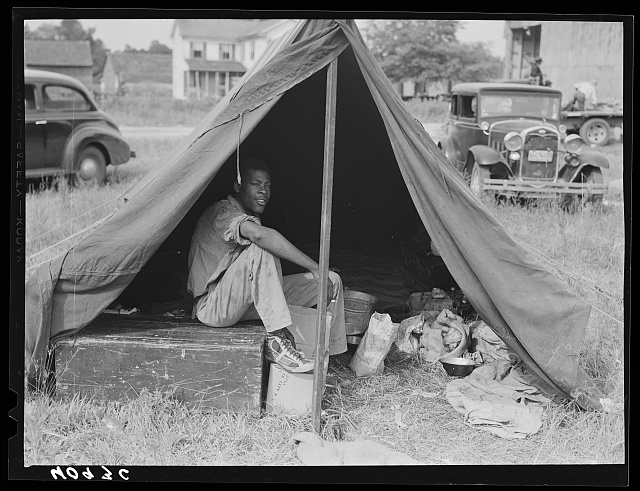

Migrant laborers from Florida in their tent next to the grading station in Belcross, N.C., 1940. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

He also photographed migrant laborers grading and packing potatoes in Elizabeth City, in Pasquotank County, N.C. That town of roughly 11,000 people had the closest freight depot to those other communities.

Belcross, N.C., 1940. Some of the farm workers stayed in old farmhouses, some in tents, some in boardinghouses in Elizabeth City’s African American neighborhoods. Others just slept in the potato warehouse. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

By 1940 migrant laborers had harvested crops in that area and in many other parts of eastern North Carolina for decades. Some had originally come from other parts of eastern North Carolina. Some came from other southern states.

Kitchen at a labor camp in Belcross, N.C., 1940. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Many had also come to the U. S. from at least half a dozen countries in the the Caribbean, as well as from Mexico.

Traveling carnival, Old Trap, N.C., July 1940. According to Jack Delano, the carnival followed the path of farm workers up and down the East Coast. A typical performance included vaudeville-style acts, music, and a movie. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Hiring migrant workers was one of the ways that farmers replaced the enslaved laborers that had harvested local crops before the Civil War.

Migrant worker and water pump at a potato grading station in Camden, N.C., 1940. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

During the Great Depression, hundreds of thousands of seasonal migrant laborers harvested crops in the U.S.

James Edwards, farm worker in Shawboro, N.C., 1940. He had apparently been on the road since 1928. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

James Edwards was among the migrant farm laborers that worked in this field of tomatoes in Shawboro, N.C., in 1940. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Those migrants moved across the country, one place to the next, swept up by the Great Depression as if in a great whirlwind and making do until they could get a toehold somewhere.

Today approximately 150,000 migrant farm laborers and their dependents come to North Carolina every growing season. Most were born in Mexico, though quite a few are also from Central America.

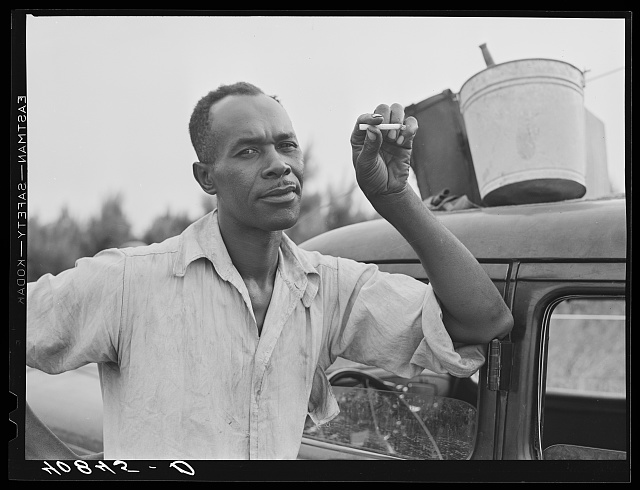

Field worker at a camp in Belcross, N.C., 1940. He and 30-some other laborers in the camp had just finished the potato harvest and were waiting for a truck to pick them up to go to another job on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

Sometimes I do not know what to make of documentary photographs. When I look at them, I feel as if I am in a dark room in a strange house and somebody has flicked a light on for just a second, then turned it back off.

It is such a brief, ephemeral look, at least in this case, of people I do not know and a place I barely know and a time that is gone.

I don’t really know who or what I am seeing, except in what I can make out in that split second of light.

Like all of us in those kinds of situations, I do the best I can: I search the lines in the faces of the people in the photographs. I look at their eyes and the way they are dressed.

On the Norfolk-Cape Charles ferry, 1940. This group of migrant laborers had finished the potato harvest in Camden County, N.C., and were headed to a new job on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Photo by Jack Delano. Courtesy, Library of Congress

I look at the color of their skin, their ages, the way they hold themselves. I look for scars on their faces and hands.

I look at the way that they look at the photographer and the way the photographer looks at them.

Of course in this case we can see that the lives of these men and women and children were hard. But without knowing more about their pasts, I do not think that I can tell if their lives as migrant laborers were harder than the lives that they left behind.

By which I mean to say something about the lives they left behind. For most of them, their earlier lives almost certainly involved sharecropping and/or field work on farms wherever they were born and in conditions that still seemed a great deal like slavery.

I suppose that, in a certain light, a life on the road could even be seen as an act of resistance, a refusal to inherit the oppressions of the past and a show of determination to escape a bondage that bound them to somebody else’s land. It could be seen as a gesture, no matter how hard a life they lived in the migrant camps, of courage and freedom.

-End-

Good one David!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. Thank you.

C

Catherine Bishir

>

LikeLike

Photographs tell us so much about people and their humanity. Just a little commentary and you have a human being, not just a subject. Your narratives are succinct, enlightening, and enjoyable, even if the subject is sad and deplorable — it’s history and it shouldn’t be unknown or forgotten. Keep ’em coming!

LikeLike

Fascinating. Thank you for posting this.

LikeLike

David, I especially liked the thoughts behind your words in the last paragraphs. I, too, have often pondered over historical photographs and felt a connection somehow with someone. This happened in your article when I came across the girl in her a Sunday hat. I saved her photo to my library. I think I will use her face as an inspiration for a character I am developing for a book I hope to write about Southport in the last quarter of the 19th century. Thank you for your continued research and articles. Pat Kirkman, Southport NC

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great pictures and story I was not around back then but my mom and dad was . Believe it or not I remember seeing place like this where my Grand Parent live who were also share cropper in South Carolina, With my Parent as kids. I pick cotton at the age of 5 going on 6 with a bag two time my size for less then a dollar a day. For me to help my family out and I remember carrying water to my Grandad who was drench in sweat at a different time digging peanuts. Anyway I can go on but I will not those picture bring back memories.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really appreciate hearing from you, Bubba. Your words make the story seem realer somehow, I guess because you lived it when you were little….

LikeLike

I remember right there on Ball Farm road every year the migrant workers came and harvested the potatoes. They stayed out in the migrant barn. A building with room after room with a wooden bed frame to sleep on every night. One night early evening there came a loud knock at the door and a lady was there at our door with her head busted open. Her and another lady were fighting over a man. Had to call the foreman to take her for stitches.

LikeLike

Hi Iona, yes, that was a big potato farm that I know well– it belonged to my great-uncle George Ball and his brother Raymond. My grandparents David & Vera Bell lived just on the other side of the canal from them. I remember my mother saying hundreds of local people used to work on the Ball farm during harvest time when she was a girl in the ’20s and ’30s, including her and most of her friends and even German POWs during World War 2. I know there was a migrant camp there too, but I don’t know exactly when the Balls started relying on migrant farmworkers– maybe after the war?

LikeLike

I lived in the George Ball house we moved there in 1969. So they were still using migrant workers up until the early 1970’s .

They lived out behind the house in the big barn with all the rooms.

I worked in potatoes when I was a teenager.

LikeLike

Beautiful last paragraph!

LikeLike

opening our eyes..

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a step up, wasn’t it. Beyond slavery or whatever lay in the past, in their families’ origins. One step in a hard path. I’m struck by the dignity of those in traveling clothes, Sunday clothes, the laborers on the porch of the store, the woman with the pipe.

LikeLike