“THE SHAD HAVE COME.” As early as the 1840s, newspapers as far away as Brooklyn, New York, advertised the arrival of fresh shad from Stumpy Point at their docks. Brooklyn Evening Star, 24 March 1848.

In memory of H.O. Golden and Horace Twiford

On May 13, 1888, a correspondent for the New York Times wrote an account of his passage along the North Carolina coast. I was especially interested in his brief, but fascinating description of the shad fishing camps at Stumpy Point, a remote village on the mainland of Dare County.

I’ll quote the passage first, then I’ll provide a little historical context for the NYT correspondent’s words.

“At Stumpy Point, . . . there is a collection of log huts, inhabited by fishermen. The seines owned by these men dot Pamlico Sound for miles. The ground on which these huts are built is so boggy that the lowest tier of bunks—the men sleep in bunks arranged after the steerage fashion—is generally half full of water.

“There is no land traveling done in this part of the world. When a Stumpy Point man wants to visit a neighbor, either on the coast or inland, he goes by boat. The country is heavily wooded and traversed by small and big streams of water.

“The fishermen have few amusements, and the principal one of these is canoe racing. Whenever a crowd gathers it is safe to assume that the argument relates to the qualities of certain canoes. They talk canoe, just as a New Yorker does opera, or horses, or baseball….

“The people of Stumpy Point and vicinity take their fish to the Old Dominion Wharf at Roanoke Island, whence it is carried to Norfolk and thence shipped North.”

The part of the NYT story that is about Stumpy Point is brief, but it still gives us a lot to work with– and a window into a side of North Carolina’s maritime heritage that we rarely see.

Because years ago, tremendous schools of shad– magnitudes larger than what we see today– began to arrive in the waters of Pamlico Sound every year in the latter part of winter and the first days of spring.

At that time of year, the shad– primarily American shad (Alosa sapidissima)– left the Atlantic, where they spent most of their lives, and moved through Outer Banks inlets into North Carolina’s estuarine waters.

They passed through the part of Pamlico Sound near Stumpy Point on their way to spawning grounds inland, mainly up the Tar River and the Neuse River and their tributaries.

From The Baltimore Sun, 9 March 1858.

At those times, hundreds, maybe thousands, of fishermen and women left their homes and came down to the shores of Pamlico Sound.

That is what the NYT correspondent was seeing. The “log huts . . . inhabited by fishermen” were the seasonal homes of fishermen who had come to Stumpy Point only for the shad fishing season.

When the shad were running, fishermen came to Stumpy Point from Hatteras, Rodanthe, and and other parts of the Outer Banks, where, in 1888, there was still very little commercial fishing.

Historical records also indicate that other shad fishermen– and sometimes women, too– came to Stumpy Point from as far north as Elizabeth City and from as far west as Hyde County.

I have heard stories from old timers that they came from as far south as Core Sound as well.

“The preparation for shad fishing at Stumpy Point is twice as large this season as the last. Fishermen on the banks and in Hyde County will make Stumpy Point their headquarters….” Carolina Watchman (Salisbury, N.C.), 3 Feb. 1887.

Most came from threadbare homes. Generally speaking, the homes were not much more refined, and had few if any more amenities, than the “collection of log huts,” inhabited by fishermen” at Stumpy Point, though hopefully their usual homes were not so sodden.

Some had been born slaves. Some were immigrants. Some of the older men had fought in the Civil War. Some had Algonquin ancestors who had built fish camps on those shores long before America was born.

During the rest of the year, some made their livings on the water in other ways– as seamen, pilots, and the like.

More, though, probably worked the land and only came down to the fishing beaches for the shad season.

“Their dwellings are on land but their homes are on the water…. All own boats, and their skill at navigating in all sorts of weather and in all circumstances seems miraculous to `land crabs.’ All are fishermen; this is their employment. The women and children tie nets; youngsters that seem scarcely old enough to tie ordinary knots tie nets with astonishing rapidity.”

The Falcon (Elizabeth City, N.C.), 5 Aug. 1887

I imagine that many of those farmers welcomed the chance to breathe in the sea air for a change. They may also have welcomed a break from the endless toil of farm life, even if a fisherman’s life was no bed of roses, either.

Most made the journey to Stumpy Point— and to other parts of Pamlico Sound—with as little as their nets, a bag of cornmeal, a few sweet potatoes, and of course a cast iron pan for frying fish.

The American shad (Alosa sapidissima) is an anadromous species, spending most of its life in the Atlantic and only coming into freshwater to spawn. A thin, silvery fish with a bluish back– typically 3 to 8 pounds as adults– they are a member of the herring family and were a seasonal staple of the early American diet. This image is a watercolor by Shermon F. Denton (1904).

They lived in the camps for several weeks, arriving soon after the ice in the shallows broke up and leaving at the height of spring.

The gill netters worked in small crews, going out at first light to tend their nets. But the haul seiners often worked day and night, sleeping in shifts– all were part of a hidden, largely unseen world on the edge of things.

The old accounts make it sound as if, on those late winter nights, and early spring nights, you used to be able to sail through Pamlico Sound and see the fires of the shad fishermen’s camps all along the shore, hundreds of them, like fireflies in the night, as far as you could see.

-2-

“The seines owned by these men….”

Now a little background on the NYT correspondent’s portrait of Stumpy Point:

In the passage I quoted above, steerage fashion refers to the crowded sleeping conditions, bunk upon bunk with very little headroom, that are reserved for the lowest paying passengers on a passenger ship.

When the writer mentioned “The seines owned by these men,” he is referring to a type of “surround net,” one probably owned by a fish dealer or other merchant, not the fishermen. Seines hang vertically in the water, buoyed at the top by floats and held to the bottom by weights.

In the state’s shad fishery, some seines were only a few hundred yards in length. However, others were more than a mile long and were so heavy, especially with a large catch, that fishermen employed horse-powered capstans or windlasses to haul them onto the shore.

A Fisherman’s Life

“In the winter of 1886, a man who had come over to Engelhard from Stumpy Point got caught by the Big Freeze and stayed with us until the ice in the creek broke up. He talked about the good fishing at Stumpy Point and begged me to come over and fish with him.

“It takes two men, sometimes more, to handle a stand of nets. I had done a little fishing, knew how to handle a boat and there wasn’t anything in farming. And so that spring I came to Stumpy Point and have lived here ever since….

“There were mighty few pound nets when I came here 52 years ago. Most of the fishing was done with gill nets. There wasn’t a gas engine in the county. We used sailboats entirely.

“We’d get out about daybreak to go to our nets and, if luck was with us, we’d get back before nightfall. But there were times when we struck a dead calm and had to use our wooden sails [oars!] and we’d do pretty well if we got in at 9 or 10 o’clock at night….”

— S. S. Nixon, Stumpy Point, N.C., 1939

-3-

“The ground on which these huts is built….”

The NYT correspondent’s phrase, “the ground on which these huts are built is so boggy…,” refers to the pocosin thickets that surrounded Stumpy Point in the 1880s, and largely still do today.

A pocosin wetland on the North Carolina coast, probably a little west of Stumpy Point in either the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge or the Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. Courtesy, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Pocosin is a word believed to be of Algonquin origin. It refers to a unique kind of wetland bog with sandy peat soil.

In a pocosin, the ground is often quite spongy, except in extended droughts. Some are forested, but when I go to Stumpy Point, I more often see only a scattering of small trees, such as pond pines and sweet bays, standing out in what is otherwise a great expanse of sphagnum moss and a dense cover of gallberry, inkberry, and other woody shrubs.

To me they seem utterly impassable, even with a good machete. More than once, I have sunken into the peat beds well above my knee.

(I should also say that I find pocosins extraordinarily beautiful in their own way, and they are incredibly important from an ecological perspective. They make up a very large part of the remaining undeveloped– not farmed, not timbered, never settled– land on the North Carolina coast.)

Around Stumpy Point, the pocosin bogs often seem to come right down to the saltwater bays along Pamlico Sound. They extend across a vast part of mainland Dare County, and they make up the largest portion of what is now the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge.

“There is no land traveling in this part of the world”

More background. In the NYT excerpt, the correspondent also said of Stumpy Point, “There is no land traveling in this part of the world.”

That was a simple fact in 1888. For all practical purposes, Stumpy Point was an island, separated from all other communities by the pocosins that I just discussed, as well as by Pamlico Sound.

In 1888, Stumpy Point did have a few local roads that connected the village’s harbor with farms a bit inland. They were made of dirt, often waterlogged, and frequently impassable even for a horse cart.

According to local oral tradition, those local roads, like the little village itself, only stood above the pocosin swamps because a local planter had forced slave laborers to build an drainage canals there before the Civil War.

To learn more about Stumpy Point’s early history, see Harold Lee Wise’s “History of Stumpy Point,” which was originally published in a 5-part series in the Coastland Times in 2006.

While perhaps two or three miles of local roads had been built by 1888, no road yet reached from Stumpy Point to any other part of mainland Dare County. All travel and trade was by boat.

The first road connecting Stumpy Point to other parts of the North Carolina coast was not built until 1926. That was largely a dredging project, requiring the excavation of two canals, one on each side of the future road. The road builders used the dredge spoil from excavating those canals to build the roadbed.

Prior to the Civil War, and the advent of steam dredging, that kind of road construction was rarely attempted on that part of the North Carolina coast. When it was attempted– as on the turnpike between Rose Bay and the Pungo River– it was only done with slave labor.

That first road to Stumpy Point came from Engelhard, a village 25 miles southwest. A decade later, the state extended the road (now U.S. 264) to Manns Harbor, 16 miles north of Stumpy Point.

-4-

“They talk canoe….”

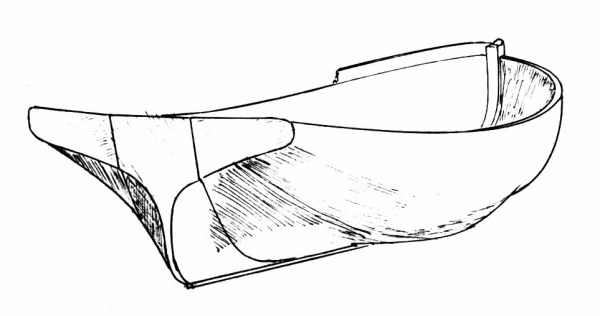

More background. When the NYT correspondent wrote, “They talk canoe, just as a New Yorker does opera, or horses, or baseball…,” he was not referring to watercraft that we would call canoes today.

The canoes to which he was referring were a very different kind of boat. In fact, I think he was mishearing or misunderstanding what local people were calling the boats– they were not actually canoes, but kunners, an understandable mistake, but quite a big difference actually.

“The Lightkeeper’s Boat,” by Edward Champney. This sketch of a sailing kunner, or small periauger, at Hatteras Island was drawn during the Civil War. Courtesy, Outer Banks History Center

(I can’t rule out, though, that local people used canoe and kunner interchangeably. That would not surprise me. Either way, the point still stands– it was still a very different kind of watercraft than what we call a canoe today.)

Built out of local juniper or cypress and typically rigged for sail, though they could also be rowed or poled in some cases, kunners were small, all-purpose workboats that had been ubiquitous sights at Stumpy Point and throughout Pamlico Sound since the late 1600s.

They were, as one coastal old-timer explained to a friend of mine, “the boat we had before skiffs.”

A kunner, dated by local lore to the 1820s, at the Cape Fear Museum in Wilmington, N.C. One of her later owners had named her the Doodle. Photo by Mike Alford

Kunners were defined by their construction. They were built from a juniper or cypress log that had been dug out, split into two halves, and joined by a wooden keel piece. In effect, the keel piece bound the left and right halves of the boat’s hull together.

Like their larger split-log cousins, called periaugers, or pettiaugers, kunners may not sound like very sophisticated boats. However, they were extremely well suited to working on North Carolina’s sounds.

They were hardy, extremely practical boats, well adapted for shoal waters and deceptively good sailors in the right wind. They could be built at little expense, with local materials, and their construction did not require a boatyard or a master boatbuilder’s skills.

For more on the history of kunners in North Carolina waters, see my and Mike Alford’s article “The Boat We Had Before Skiffs.”

Also, by 1888, when the NYT correspondent visited Stumpy Point, many kunners hardly looked roughhewn. Some were quite elegant looking, and not primitive seeming in the least.

In fact, by that time, kunner builders not infrequently added decks and elaborate interior planking to their boats, so that from a distance you or I would not even have recognized them as log boats.

Drawing of the kunner Doodle, stern view, by Mike Alford

Skiffs and other plank-built boats would supplant kunners on Pamlico Sound in the late 1800s and early 1900s. However, plenty of them could still been seen in the waters around Stumpy Point in 1888. Coastal families used them for just about everything: fishing, freight hauling, visiting friends and family, going into town on shopping trips, and much else.

And, as the NYT’s correspondent heard, and maybe witnessed, the shad fishermen at Stumpy Point also raced their kunners, and they no doubt did so with passion and aplomb.

-5-

“Old Dominion Wharf at Roanoke Island”

Finally, the article’s reference to the “Old Dominion Wharf at Roanoke Island” is a reference to the Old Dominion Steamship Company’s wharf on Roanoke Island’s North End.

In the 1880s, the Old Dominion Steamship Co.’s steamers operated throughout Pamlico and Albemarle Sound. They made regular stops at the larger seaports on Pamlico Sound, such as New Bern and Washington, but also at a few fishing villages and lumber mill towns.

On Pamlico Sound, Old Dominion steamers played an especially important role in the fish trade.

On a regular schedule, they transported fish to Elizabeth City, N.C., and to Norfolk, Va., where they were loaded onto railroad cars and sent to markets as far away as New York City by the next morning.

The steamer Manteo was built for the Old Dominion Steamship Co. at the Pusey & Jones shipyard in Wilmington, Del. This photo is from 1887. In the late 1880s, the Manteo made regular runs between New Bern, N.C., and Norfolk, Va., with a stop at Roanoke Island. Courtesy, Hagley Museum and Archive, Wilmington, DE.

In those days– before the age of gasoline vehicles and modern highways– steamship lines and railroad companies often coordinated their routes and schedules, much as a subway and bus system might coordinate the movement of passengers in an American city today.

-6-

“Three houses built on piles”

The “log huts, inhabited by fishermen” that the NYT correspondent saw at Stumpy Point were not the only kind of shad fishing camps on Pamlico Sound in that last half of the 19th century.

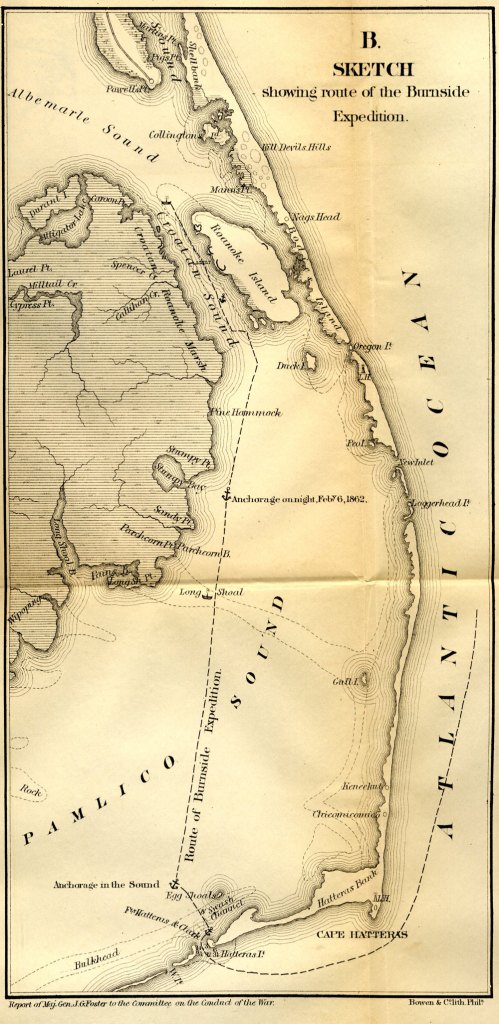

During the Civil War, for example, a fleet of U.S. naval vessels anchored off Stumpy Point on its way to make an amphibious assault on Confederate forces at Roanoke Island.

“Sketch showing route of the Burnside Expedition” (including its anchorage off Stumpy Point on the night of Feb.6, 1862), in “Report of Maj. Gen. J. G. Foster to the Committee on the Conduct of the War,” Supplemental Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War (Washington: GPO, 1866). From North Carolina Collection, Wilson Library, UNC-CH

Writing years later, one of the navy sailors in that fleet described a very different kind of fish camp at Stumpy Point.

In the February 18, 1893 edition of his hometown newspaper, the Lewisburg Chronicle, in Lewisburg, Penn., he wrote:

“Along the shore at Stumpy Point were three houses built on piles—fish houses for the negroes in the spring. These are the finest shad fisheries just here. The shore is marshy, inland for miles, and they have built a place on piles for a windlass, drawn by a horse to drag in the nets.”

That was a seine fishery, where large gangs of 20 or even 30 African American fishermen harvested shad well into the spring, while a no less sizable contingent of black women clean, salted, and packed the shad into barrels for shipment across much of the Eastern Seaboard.

Up to the time of the Civil War, those fishermen and women typically worked around the clock, all day and all night, sleeping in shifts like sailors at sea.

Beginning in the 1880s, the shad fishery was the driving force behind an economic boom in Stumpy Point. Between 1888 and 1914– according to Harold Lee Wise’s “History of Stumpy Point”– the village’s population nearly tripled, to some 90 families. By the 1930s, Stumpy Point was often called “The Shad Capital of the World” and for a brief period it was said to be the busiest fishing port on the North Carolina coast. This photograph is undated, but was probably taken in the 1940s. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

I cannot be sure, but I suspect those seine fishermen came from the north side of the Albemarle Sound.

Most likely, a sizable part of them belonged to the large class of free African Americans and Native Americans who made their homes on that part of the coast. Others, I would expect, were slaves.

At Stumpy Point in 1862, they were probably using one of the mile-long seines that I mentioned earlier.

At that time, a single haul could take half a day, and the weight of the seine and the size of the catches led the fishermen to use horse-powered windlasses or capstans to haul the fish to shore.

Fishermen setting out or repairing a pound net, Stumpy Point, N.C.. 1925. Pound nets came to dominate the shad fishery in the vicinity of Stumpy Point in the 1890s. From the Ben Dixon MacNeill Photographic Collection, North Carolina Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill

-7-

“Camps around the edges of the place….”

There were other kinds of fish camps on Pamlico Sound in those days as well.

Some fishermen did not bother to build a hut or a cabin on the shore. They just used their sails for tents or, if they had a little sloop or a small schooner, just anchored up one of the local salt marsh creeks and slept in their boats.

This is a quote from a commercial fisherman I came to know, and revere, in Stumpy Point many years ago.

“When my dad was coming along, there was no power in boats. It was all sailboats. They had a rough life…. They were away from home, and with sailboats it was too far from home to come back every night. Most of the time, they’d spend a week. They had camps around the edges of the place, but if they were away from the camp, night come, they just went up a creek somewhere and got out, took their sail, made them a tent and cooked on wood fires.”

— Hildred “H. O.” Golden, Stumpy Point, N.C., 2005.

H. O.’s father was from Core Sound, not Stumpy Point, and he was describing his father fishing on the south end, not the north end, of Pamlico Sound in the late 1800s. All the same, I think that his words capture a bit of what many a fisherman’s life was like at Stumpy Point, too.

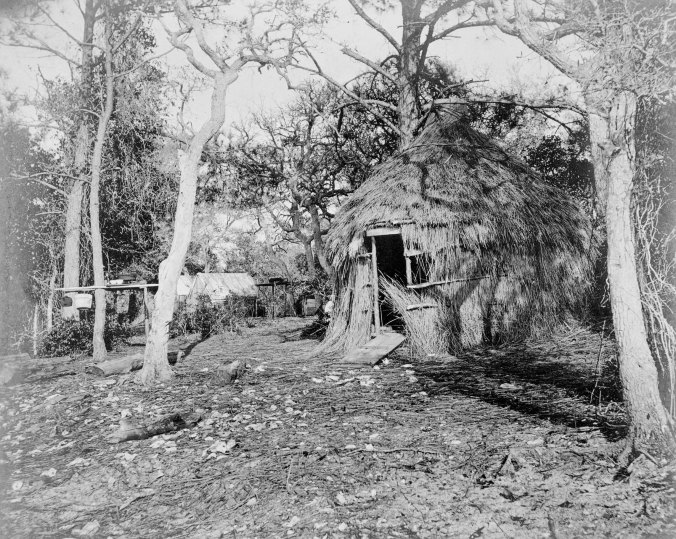

Other fishermen at Stumpy Point may have fashioned their camps out of salt marsh grasses. At that time, shad fishermen often used marsh grasses to build round, thatched huts along the shores of the Lower Neuse, some 80 miles south of Stumpy Point.

Fishermen at Stumpy Point and elsewhere on the northern side of Pamlico Sound may have done the same.

A thatched shad fishermen’s camp, made of marsh grasses, on the Neuse River, in the vicinity of James City, ca. 1900. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

These are just small glimpses at a whole world of fish camps, now long gone, as are, by and large, the great schools of shad as well.

But I still think of them, and the fishermen who gathered on those shores, and whose cook fires lit the night.

How I would have liked to sit by their fires, and how I would have liked to listen to their stories.

* * *

A Note on Sources

The quote from fisherman S. S. Nixon comes from a Federal Writers’ Project interview in 1939, when Nixon was 75 years old.

Nixon was originally from a farm family in Engelhard, but moved to Stumpy Point to go fishing in 1886.

That interview can be found in the Thadeus Farree Papers at the Southern Historical Collection, UNC-Chapel.

The quote from Hildred “H. O.” Golden comes from my story “H. O. Golden: A Man’s Work,” which appeared in my “Listening to History” series in the Raleigh News & Observer on June 12, 2005.

I dedicated this story to H. O. and to his friend Horace Twiford, two old friends whom I first got to know in Stumpy Point back in the winter of 1983-84.

H. O. and Horace were as different as night and day, but they were both special people, old school in all the best ways, and I had tremendous respect and admiration for both of them. I count myself very lucky to have known them.

I count myself very lucky to have found your website of such well researched and well written accounts of Eastern NC history. I enjoy every posting and the passion and depth of writing that bring so much alive, reviving the hard times and keeping the history from vanishing.

LikeLike

Thank you so much– your words mean a lot to me.

http://www.davidcecelski.com

LikeLike

Thank You.I was introduced to Mr Golden by his daughter Sheila.I had torn open my shrimp trawl and it was missing some webbing.Mr Golden repaired my net and we spent a few evenings together.He repaired my net and added in some new webbing that was missing.Takling and mending net came natural for Mr.Golden.It was my pleasure to have a cup of coffee and Pray with Mr.Golden.I was new at shrimp trawling and he took the time to show me how to set up my net so it would catch better.More than that it showed how much he loved the water and his love and brotherhood for a stranger and a fellow fisherman.He past away in 2009 and is buried on Stumpy point graveyard.

LikeLike

Good to hear from you– and I appreciate you reminding me of H.O. He was top flight– and he must have cottoned to you because he had high standards! Thanks for writing– David

LikeLike