This is the sixth photo-essay in my series “Working Lives: Photographs from Eastern North Carolina, 1937 to 1947.”

You can find my introduction to the series here.

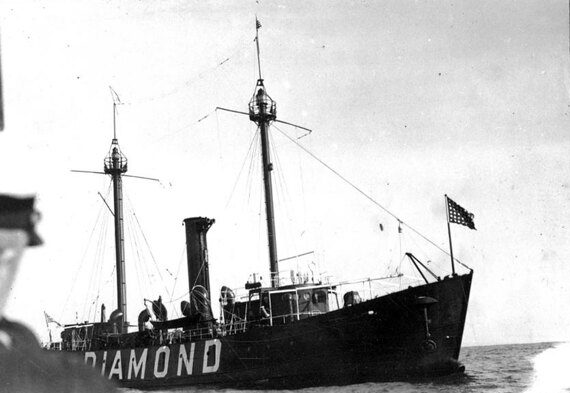

In December 1939, one of the NCDC&D’s photographers, Bill Sharpe, visited the United States lightship Diamond Shoals where it was moored in the open sea 20 miles east of North Carolina’s Outer Banks.

He took these photographs, and a few others that are also at the State Archives, but which I am not featuring here, while he and a Hatteras charter boat captain were the guests of the lightship’s captain and crew.

I have only known one lightship crewman in my life, Mr. Joe Floyd. Joe served for many years on the lightship Relief, where he and his Coast Guard crew mates had the job of relieving the Diamond Shoals and other lightships when they were in need of repairs or maintenance.

As I go through these photographs, I am going to feature several excerpts from an interview that I did with Joe more than 20 years ago at his home in Wilmington, N.C.

Joe served on the Relief in the 1950s, but I think his memories still help to bring these photographs from a slightly earlier time to life.

-1-

A crewman reading in his bunk on the Lightship Diamond Shoals, 1939. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Anchored far out in the Atlantic, the Diamond Shoals Lightship was on station day and night, every day of the year.

Its one duty: warn merchant ships away from Diamond Shoals, the long, constantly shifting labyrinth of underwater sandbars built up by the convergence of the Gulf Stream and the Labrador Current and extending some eight miles out into the sea from Cape Hatteras.

To do its duty, the lightship carried two powerful 500 mm. electric lenses– two in case one malfunctioned– as well as a fog horn and a radio beacon.

When I interviewed him, Joe Floyd told me:

“If it wasn’t a storm or a heavy fog, a lightship could get tremendously boring. We’d scrape and chip and paint from the bow to the stern, and as soon as we got through, we would start right over.

“We did a lot of reading. In the summer we’d rig us up a line and swing out off the fantail and swim all around that lightship. We fished a lot too, especially around Frying Pan [Shoals].”

-2-

The Lightship Diamond Shoals at her station in the Atlantic, 20 miles east of Hatteras Island. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

The first lightship stationed off Cape Hatteras went on duty in 1824. The lightship in these photographs however was part of a long line of lightships that had begun in the late 19th century– one of them was actually sunk by a German submarine during the First World War.

The Diamond Shoals Lightship that we see in this photograph first went on duty in 1922.

A federal agency called the U.S. Lighthouse Service had operated the nation’s lightships until just a few months before this photograph was taken. On July 1, 1939, the Roosevelt Administration merged the U.S. Lighthouse Service into the U.S. Coast Guard.

At the time of the merger, U.S. Lighthouse Service personnel served on a total of 30 lightships in U.S. coastal waters.

In our interview, Joe told me:

“The ship was made for sitting at sea. It was not made for moving around much. We were usually 25, 28 miles out to sea and in about 50 feet of water. We couldn’t see land on any station, but on Diamond Shoals, on a real clear, crisp day, we could climb up the foremast and see the Hatteras Lighthouse.”

-3-

The lightship’s cook in his galley, 1939. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

According to photographer Bill Sharpe, the lightship’s crew worked 60 days on, 27 days off, throughout the year.

One expects that only a certain kind of person bore that kind of duty gracefully.

The lightship’s crew only saw their families every third month, and visitors were not commonplace.

In the summer and fall, the lightship’s captain occasionally welcomed Gulf Stream fishermen on board for a chat and a cup of coffee. But in the winter, the crewmen were largely left to their own society.

During those months, the men on the Diamond Shoals had little company other than the crew of the tender that brought them provisions and supplies once a month.

Joe remembered his time on lightships:

“The lightship crews were special people. A lot of people can’t take that isolated duty. You’re just too confined and too alone. We all got along good together and worked together. You became more like a family on a lightship.”

-4-

The lightship’s captain posing for the photographer in the wheelhouse, 1939. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

When I talked with Joe, he recalled how quickly a lightship crew’s days could turn from dull routine, painting and repainting, scrubbing decks, and the like, into something very different.

Joe told me:

“We were on Diamond Shoals when Hurricane Hazel hit in ’54. They brought us all the fuel and all the water we could fit in our tanks to try to make us lay low in the water, then they just left us to it.

“The big Navy vessels were out there riding out the storm with us so they don’t get beat up at the dock, and I’m looking over at an aircraft carrier and the waves are breaking over the flight deck.

“Everybody was sick except two of us. There was an engineer from Morehead City named Earl Styron and myself. Earl kept the main engine running. If something happened, we would try to keep it into the sea.

“As far as the deck was concerned, we had to make sure that our light and radio were operating and that we had a good lookout for ships around us.

“The chief engineer on the lightship was a guy named Andrew Holeman. We lost Andrew. We didn’t know where he was. Earl and myself started looking, and when we went down into the very bottom of the engine room, we could see the bottom of his shoes. He was actually lying in the bilge throwing up. He was in bad shape. We would tie the guys in their bunks and just let them have at it.

“I spent most of my time on a tall stool between the wheel and the forward portholes. I would wrap my legs around the stool and put my arms in the dogs of the portholes and just try to ride it out.

“You could look out the portholes and all you could see was water. There was no horizon. The water was just everywhere. It’s almost like you’re part of the water.

“When the ship is riding on the anchor, it noses down into the sea, then it will come back up and go back down again. But during Hazel it would go down into a sea and try to come back up, and another big sea would hit it. It just kind of stayed nose down and quivered.

“There have been lightships sunk during storms and lost, and there’s been quite a few of them rammed. The Olympic, the Titanic’s sister ship, cut the [lightship] Nantucket in two. That was in ’33, I believe it was. There were 11 people on there and seven of them died.

“You knew that danger was there. You’re tied down. You can’t run. …”

Here we see the one of the Diamond Shoals’ crewmen descending a mast after servicing or cleaning one of the vessel’s two beacons. Photo courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

Quite likely, every crewman in these photographs was on board the Diamond Shoals during the great 1933 hurricane.

During that storm, winds and waves pounded the lightship so badly that Capt. Claude Austin decided to raise the vessel’s great three or four ton anchor and run into the wind for fear that the lightship would be pounded into the sea if he stayed where he was.

The waves smashed into the lightship’s hull with such power that six of the eight-man crew were injured and unable to perform their duties.

That left only Capt. Austin and the engineer to steer the lightship into the storm. If they had failed to keep the wind from turning her sidewise into the waves, the lightship could well have rolled over and none of the lightship’s crew would have ever seen their homes again.

Capt. Austin and his engineer held the lightship steady, and by the time the seas began to calm, the craft was off Frying Pan Shoals, 120 miles to south of where she had been anchored when the storm hit.

Near the end of our interview, Joe Floyd reflected on his career as a crewman on the lightship Relief and the experiences that he had while serving on the North Carolina coast.

Joe said:

“You know, I think about the Relief all the time. I think about morning out there a lot. There’s nothing greater than the sun coming up over the ocean and the sounds and smells early in the morning.

“When I think about the lightship, that’s usually the first thing I think about.

“Night could get sort of lonely if you had the midwatch, but it’s not like you’re sitting out there and nothing’s going on. You could hear sea life coming up for air and flipping and making all kinds of noises in the dark. You couldn’t see any of it, but there were things happening all around you.”

-End-

Great read as always.

LikeLike