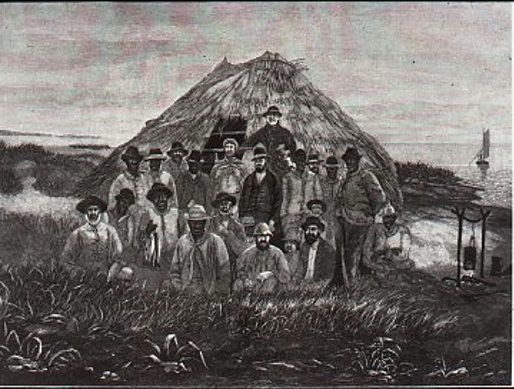

Engraving of mullet fishermen at their camp, Shackleford Banks, circa 1880. From George Brown Goode, ed., The Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States, 5 secs. (Washington, DC: Commission of Fish and Fisheries, 1884-1887), sec. 5, vol. 2

The following illustrations will accompany my lecture at the Cameron Art Museum in Wilmington, N.C., this Saturday, February 21, at 1 PM.

Titled “Freedom and the Sea: African American Life on the Cape Fear,” my lecture will draw heavily from my book The Waterman’s Song.

I am putting the illustrations up here because I will be giving the lecture outdoors next to the museum’s extraordinary sculptural work of African American Civil War soldiers.

Titled “Boundless,” the sculpture was created by North Carolina-based artist and Duke University professor Stephen Hayes.

Because we will be outdoors, I will not be able to use PowerPoint slides or other audio-visuals with my lecture, so I thought this might be a good way to share illustrations with the audience.

For those attending the event, you will be given a QR code that links to this page.

During my lecture, I will be inviting you to use the QR code to view the illustrations below on your smart phone.

They include photographs, drawings, maps, manuscripts, and historical artifacts.

All speak to the history of African American maritime life and the struggle for freedom in Wilmington and throughout the North Carolina coast before and during the Civil War.

To those who can join me at CAM: I look forward to seeing you. To those who can’t be there, I looking forward to seeing you next time.

David Cecelski

“Thy way is in the sea, and they paths in the great waters, and thy footsteps are not known.”

Psalms 77:19-20

ILLUSTRATION 1: THE WATERMAN’S SONG

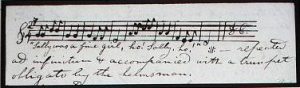

From my book The Waterman’s Song: “In 1830 Moses Ashley Curtis heard slave boatmen on the Cape Fear River singing this song and recorded its refrain in his diary. The piece is apparently a version of the sea chantey “Sally Brown” about a beautiful Jamaican mulatto, and sailors and boatmen spread the chantey around the globe.” To me the song spoke to the ways in which the sea connected the people of the African Diaspora and their descendants throughout the Atlantic and beyond. The title of my book The Waterman’s Song: Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina was inspired by this single line of music. Courtesy, Southern Historical Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill

ILLUSTRATION 2: AN AFRICAN AMERICAN MARITIME HERITAGE

Morton’s Millpond near where I grew up on the North Carolina coast. From The Waterman’s Song: “As I wrote The Waterman’s Song, I often hummed the sea chantey sung by the black boatmen who passed Moses Ashley Curtis in 1830. Their version of “Sally Brown” reminded me of other, more recent chanteys that I heard when I was a child: the raucous songs hoisted by black menhaden fishermen as they hauled purse seines out of the Atlantic and the vibrant melodies sung by black women while they worked in Pamlico Sound crab canneries. Playful, reverent, or wistful, “Sally Brown” and the more recent songs helped pass the time and lighten the labor, but they also brought forth joy, hope, and a faith deepened by sorrow and affliction. Their singers’ struggles, like the songs themselves, have deep roots in an African American maritime heritage that has nearly been forgotten. And no matter how much maritime life has changed from the slavery era to today, I will suspect that African Americans, slave and free, found their hopes uplifted and their lives unbounded merely by the nearness of the sea, by working on the water, and by the vast horizon over Pamlico Sound and the Atlantic. I have never known a soul who did not.” Photo by David Cecelski

ILLUSTRATION 3: THE MEANING OF THE SEA

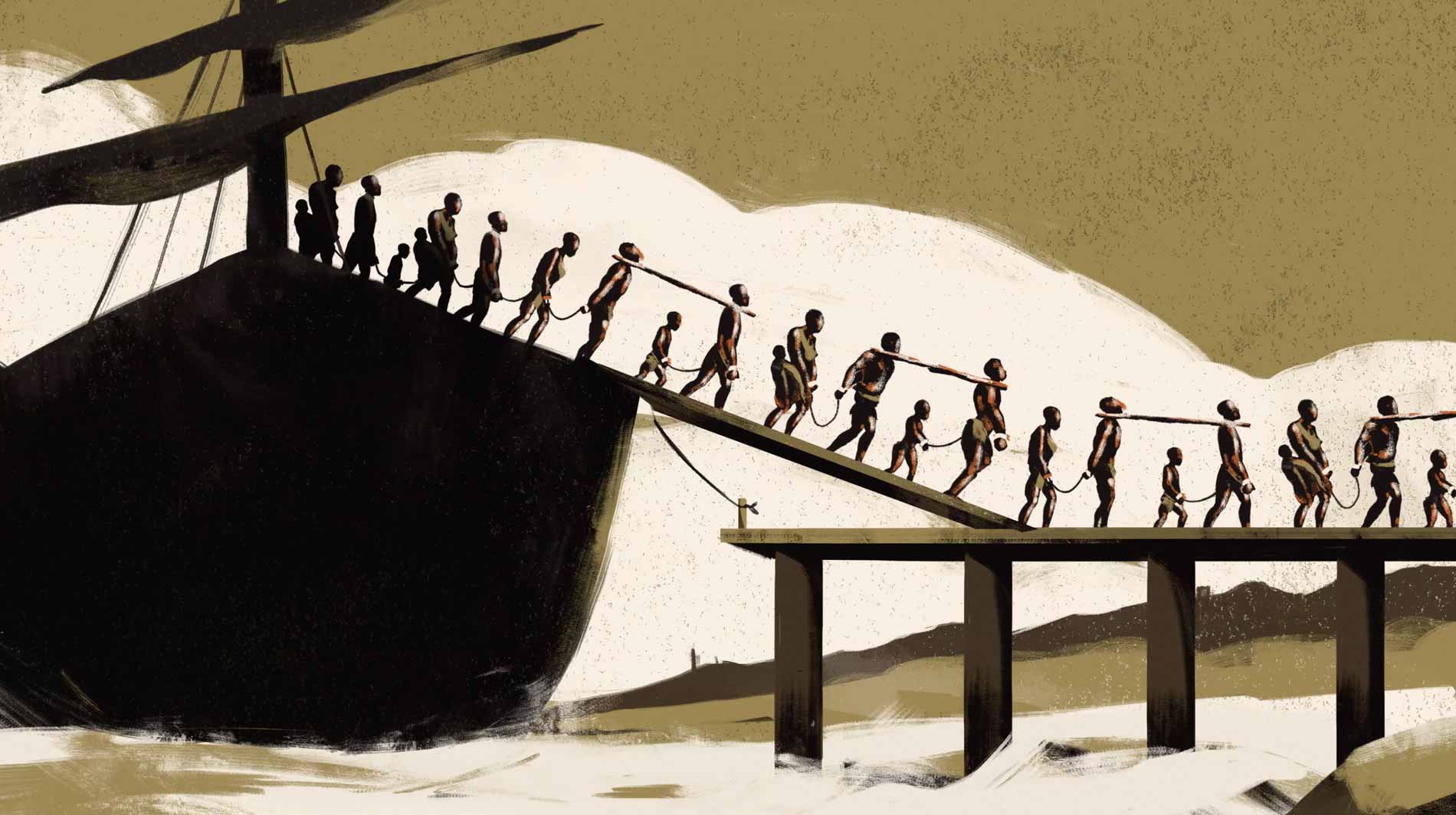

For Frederick Douglass, the sea meant freedom. While still enslaved, he looked out at the sea and saw the “beautiful vessels, robed in white” and dreamed how they would “yet bear [me] to freedom.” In The Waterman’s Song, I discuss how many Africans being held captive on the North Carolina coast had deeply held spiritual beliefs grounded in the sea. I observe, for instance, how “shells had a central role in Igbo and Mande ancestral shrines in the South, including shrines to water deities such as the Igbo spirit Idemili. Slaves of Kongo ancestry in tidewater North Carolina used sea shells to adorn graves.” At the same time, I try never to forget that the sea had many meanings, to many different African peoples, and also evoked many different kinds of ancestral memories, including the collective trauma of the Middle Passage. Courtesy, Equal Justice Initiative

ILLUSTRATION 4: THE SEAPORT OF WILMINGTON

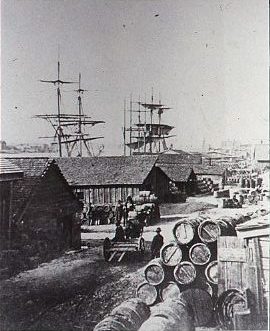

Barrels of turpentine at the docks in Wilmington ca. 1880. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina

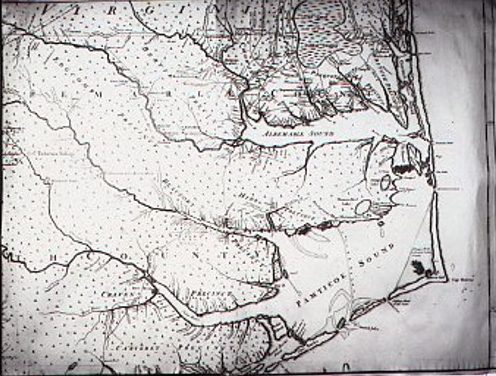

ILLUSTRATION 5: A WORLD OF RIVERS AND SEAS

The Lower Banks, Outer Banks, and the major sounds of North Carolina. Inset from a map by Edward Mosely, 1733. Courtesy, North Carolina Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill

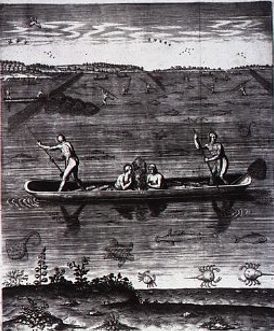

ILLUSTRATION 6: “WHERE IT IS ALMOST IMPOSSIBLE FOR WHITE MEN TO FOLLOW “

From The Waterman’s Song: “Native boatmanship gained a singular reputation among the European colonists, who frequently found themselves at a loss on coastal salt marshes, rivers, and sounds. The colonists rather regretfully came to appreciate Indian small-craft skills first during the Tuscarora War of 1711-1713, a monumental and very bloody conflict that ultimately forced all coastal Indians into political subjugation or exile. In 1713, when the Matchapunga remained one of only two tribes that had not fallen to the English, the colony’s presiding governor cautioned that his Indian enemies would not be easy to defeat. ‘They have got … boats and canoes, being expert men,’ Thomas Pollock warned, and they would voyage into `lakes, quagmires, and cane swamps … where it is almost impossible for white men to follow them.” This scene is a Theodor De Bay engraving of John White’s drawing “Their manner of fishynge in Virginia,” ca. 1590. During the Roanoke voyages of 1584-1590, White drew the composite portrait of Algonquian fishing methods in the vicinity of the Outer Banks on which this later engraving is based.Courtesy, North Carolina Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill.

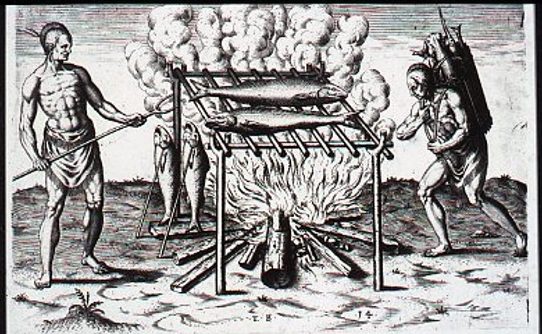

ILLUSTRATION 7: “THE BOOK OF NATURE”

From The Waterman’s Song: “… it was the colonists’ slaves who best watched and learned from the Indian fishermen. They discovered what late winter day to abandon hunting camps to harvest the great waves of spawning shad that migrated out of the Atlantic into Pamlico and Albemarle Sounds. They learned what lunar tide beckoned the bottlenose dolphins into local inlets, in what current to erect a fishing weir, and what late summer wind shift marked the coming of the jumping mullet. `Being out of doors a great deal of the time,’ as a Chowan River slave named Allen Parker later wrote, the slaves ‘learned many things from the book of Nature, which were unknown to white folks.” (This is a Theodore De Bay engraving of coastal Algonquians, based on a John White drawing made ca. 1590. Courtesy North Carolina Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill.)

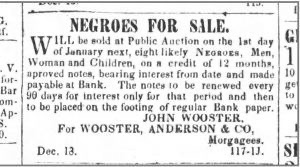

ILLUSTRATION 8: THE SLAVE TRADE

From my article “A Local History of Human Trafficking”: “Before the Civil War, human trafficking within Eastern North Carolina was commonplace. There were at least occasional slave markets in every village and town of any size. At that time, the buying and selling of enslaved laborers was incessant, constant and never ending; not the exception, but the rule. As Guion Grffis Johnson wrote in her 1939 masterpiece, Antebellum North Carolina: A Social History, `Slave traders, or speculators, as they were usually called, were constantly coming and going in every North Carolina community where the slave population was large. They bought slaves for the market in the Lower South or for any planter who might be in need of laborers.'” This notice of a slave auction appeared in a Wilmington newspaper, The Tri-Weekly Commercial, on January 1, 1852. At that time, there were far more enslaved African Americans in Wilmington than free people of any color.

ILLUSTRATION 9: DAVID WALKER’S APPEAL

This was the frontispiece to David Walker’s Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, which was published in 1829 and was one of the most important anti-slavery statements in American history. I thought that I should include it here as a reminder that for all its history of oppression and injustice, Wilmington was also home to a powerful tradition of black resistance and freedom fighting. This is from my article “The African Church at the Corner of Second and Walnut”: “David Walker… was born a free black in Wilmington on Sept. 26, 1796…. He would leave Wilmington when he was a young man. Of that moment, he later wrote, `If I remain in this bloody land, I will not live long…. I cannot remain where I must hear slaves’ chains continually and where I must encounter the insults of their hypocritical enslavers.'”

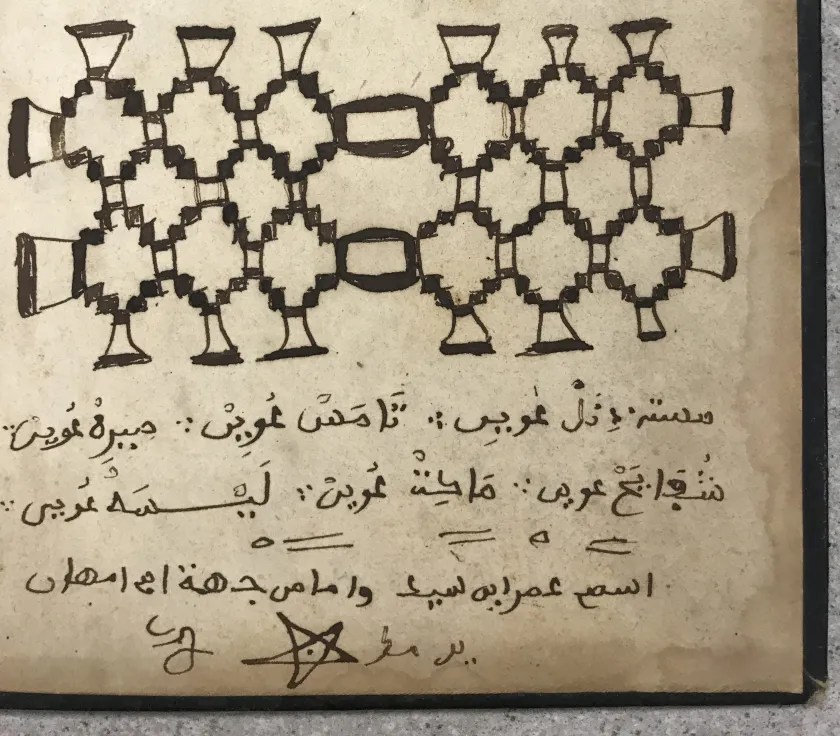

ILLUSTRATION 10: OMAR IBN SAID I

This is a partial view of an Arabic inscription written by Omar ibn Said, an Islamic scholar who was held in slavery for most of his life in Wilmington and other parts of the Cape Fear. Omar was a Fula born in or about 1770 in Futo Toro, a region along the middle Senegal River valley east of Dagna in present-day Senegal. When young, he studied the Arabic literary traditions of West and North Africa. In his surviving letters and other writings, he referenced classical Arabic literature dating as far back as the 10th century A.D. I include this image here as a reminder of the diversity of African American maritime culture in Wilmington and throughout Cape Fear in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. At that time, the large majority of the seaport’s population were enslaved black people. They had been taken from many different parts of Africa, the Caribbean, and North America and spoke dozens of languages, including Arabic, and you would have heard all of them if you spent much time along the wharves or walking the streets of Wilmington. This inscription is in the Eliza Owen journal at the New Hanover County Public Library in Wilmington.

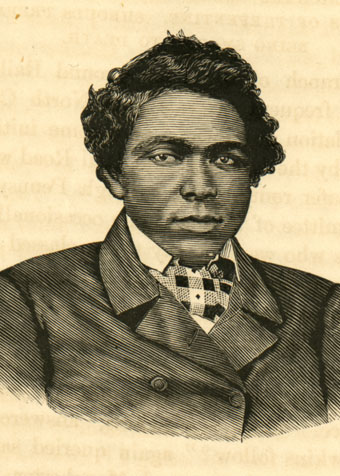

ILLUSTRATION 11: OMAR IBN SAID II

This is the only known portrait of the enslaved Islamic scholar Omar bin Said. Dating to sometime around 1850, the tintype is preserved in the Owen and Barry Family Collection at the local history room at the New Hanover County Public Library in Wilmington.

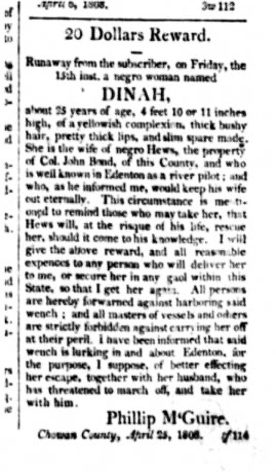

ILLUSTRATION 12: A SLAVE PILOT IN EDENTON

From The Waterman’s Song: “In 1808, a slave river pilot named Hews confronted his wife’s master, Phillip McGuire, in the seaport of Edenton, N.C. Hews could no longer bear McGuire’s claims on Dinah. The boatman threatened to steal her away. If he got the chance, the slave pilot declared, he would `keep his wife out eternally.'” The reward notice goes on to say that, “This circumstance is mentioned to remind those that may take her [i.e., capture her], that Hews will, at the risque [sic] of his life, rescue her, if it comes to his knowledge…. I have been informed that said wench is lurking in and about Edenton, for the purpose, I suppose, of better effecting her escape, together with her husband, who has threatened to march off, and take her with him.” Hews… belonged to an elite fraternity of black watermen both irreplaceable to the plantation economy and subversive of the racial bondage that fueled it. He proved true to his word. That April, Hews and Dinah vanished from Edenton. Together they had seized at least a moment of freedom on the broad waters of the Albemarle Sound.” Reward notice from the Edenton Gazette and North Carolina Advertiser, 27 April 1808.

ILLUSTRATION 13: W. H. SINGLETON AT ADAMS CREEK

William H. Singleton escaped from slavery on a plantation on the North Carolina coast and served as a sergeant in the United States Colored Troops. In The Waterman’s Song, I described a moment circa 1850, when he was a young boy who had escaped and tried to reach his mother on the far side of a bay called Adams Creek. “Trapped on the creek’s western bank, [he] sought desperately to reach the other shore…. Only that creek stood between him and his family, and twilight was upon him. He would soon be at the mercy of the slave patrol. Looking over the darkening horizon, Singleton spied a solitary fishermen so far away that he could not tell the man’s race. Was he African American and a likely ally? Or white and a likely danger? Unable to say for certain, Singleton staked his life on the fact that he had rarely seen a white fisherman among the crowds of watermen who fished on the Lower Neuse. `I knew he must be a colored man,’ Singleton later remembered, `because the white people as a rule did not fish.'” He called to the fisherman, who indeed turned out to be black, and the fishermen carried him across the bay. He was soon with his mother again. Photo courtesy of Leroy Fitch, New Haven, Conn.

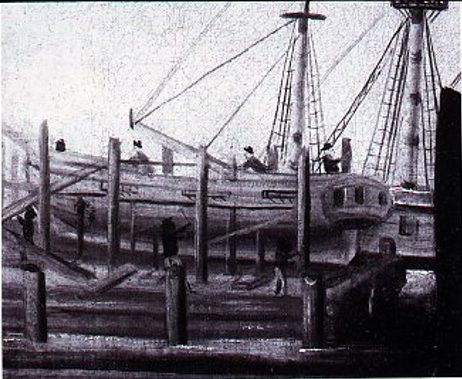

ILLUSTRATION 14: THE SHIP CAULKERS

African American ship caulkers such as the ones seen in this oil painting were among the many black ship’s shipbuilders, iron workers, sail makers, cord swains, and other tradesmen who worked in shipyards and boatyards on the North Carolina coast. From The Waterman’s Song: “In 1782 …, at the `most commodious, and … best shipyard in the providence [sic],” on Indiantown Creek, in Currituck County, N.C., Thomas MacKnight was said to own `the most valuable collection of Negroes in that country– They were able to build a ship within themselves with no other assistance than a Master Builder.” Courtesy the Mariners Museum, Newport News, Va.

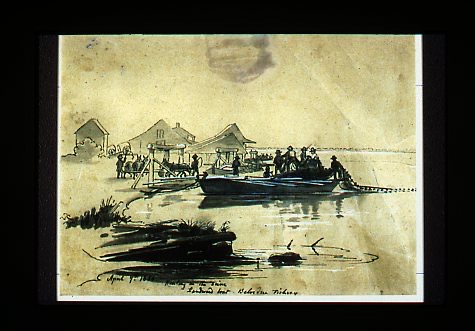

ILLUSTRATION 15: THE SHAD AND HERRING FISHERY I

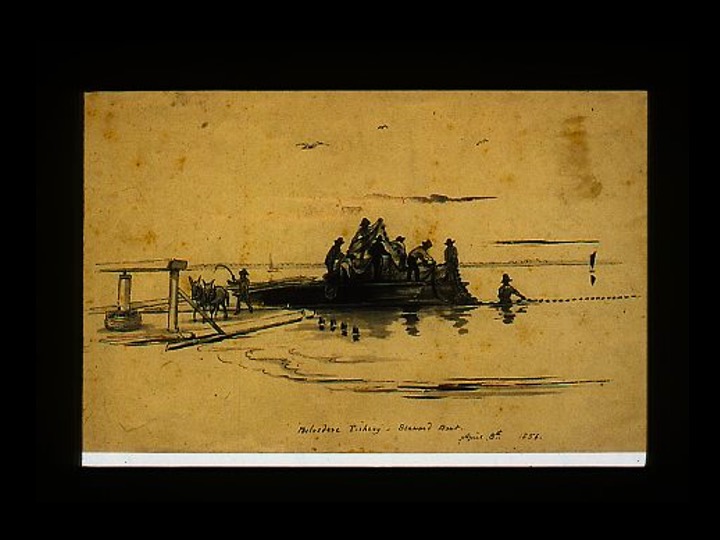

“Landward Boat,” Montpelier Fishery, 1856, by David Hunter Strother. Courtesy, West Virginia and Regional History Collection, West Virginia University (WVU). One of the largest commercial fisheries in North America was located on the North Carolina coast– the seine fishery for herring, shad, and rockfish– and it was wholly reliant on thousands of African American laborers, both many whom were free and many whom were enslaved. From The Waterman’s Song: “In 1840 William Valentine visited a seine fishery by the Albemarle Sound. Great crowds gathered to watch African American fishermen catching hundreds of thousands of shad, rockfish, and herring. The black boatmen wielded seines massive enough to span whole inlets and river mouths. They fished around the clock seven days a week, working at night in the flickering glow of torches, bonfires, and lanterns.”

ILLUSTRATION 16: THE SHAD AND HERRING FISHERY II

“Seaward Boat,” Belvidere Fishery, 1856, by David Hunter Strother. Courtesy, West Virginia and Regional History Collection, WVU. From The Waterman’s Song: “When the herring began their run into Albemarle Sound, approximately 3,500 African Americans labored in the seine fishery. Thousands more independent fishermen of all races used bow nets, stake nets, and gill nets to harvest the spawning fish…. Even men and women so downtrodden that they could not build a dugout canoe could still fashion an ash bow net and a jerry-rigged stand that leaned far enough over a small creek to fish successfully.”

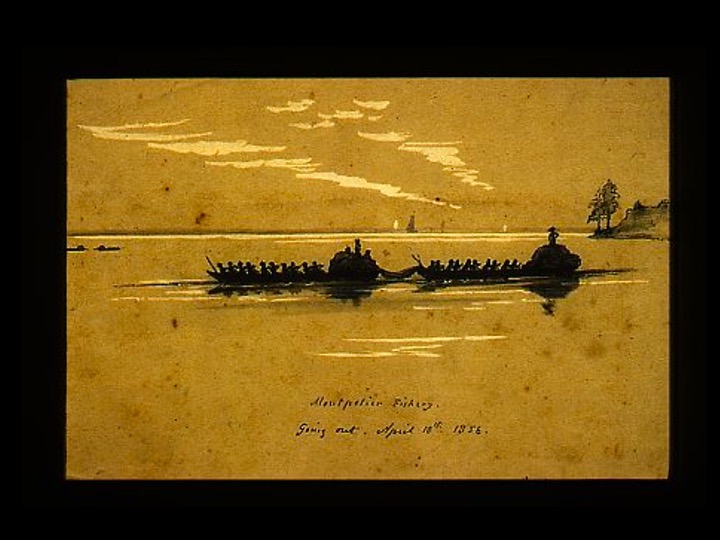

ILLUSTRATION 17: THE SHAD AND HERRING FISHERY III

“Going Out,” Montpelier Fishery, 1856, by David Hunter Strother. Courtesy, West Virginia and Regional History Collection, WVU. From The Waterman’s Song: “The fishermen combed the water with gigantic seines that averaged approximately 2,500 yards in length and ranged from 12 to 24 feet in depth…. In crews of 8 to 20, they laid out the seines in two long rowing boats…usually 40 to 60 feet long….The fishermen first packed the seine on the stern platforms of their two boats. They rowed together approximately a mile directly off the landing, and then the helmsmen steered the boats in opposite directions, parallel to the shore, as the two crews slowly laid out the seine between them.”

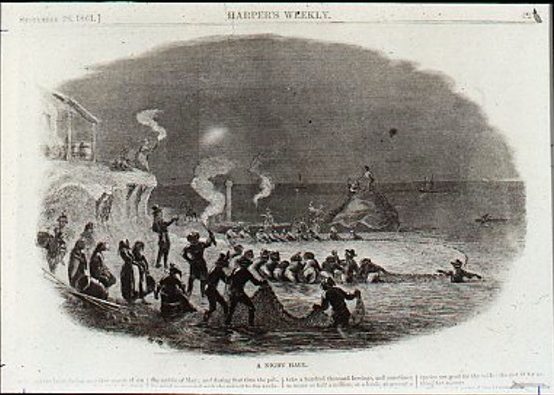

ILLUSTRATION 18: THE SHAD AND HERRING FISHERY IV

A Night Haul,” by David Hunter Strother, from Harper’s Weekly, September 28, 1861. Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina. From The Waterman’s Song: “The size of their catches confounds the imagination. The black fishermen often caught 100,000 herring in a single haul and occasionally more than a million. As a general rule, fishery owners estimated that their workers caught one-tenth to one-twentieth the number of shad as herring…. Fishing crews caught far fewer rockfish, but at rate moments rockfish runs sometimes rivaled the harvest of the smaller fish…. In 1858 slave fishermen at W. R. Capehart’s Black Walnut Point fishery in Bertie County purportedly caught 30,000 pounds [of rockfish] in one haul.”

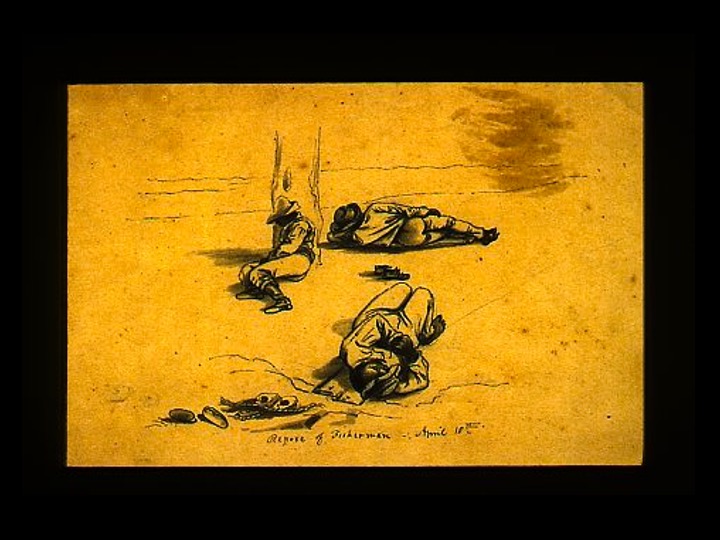

ILLUSTRATION 19: THE SHAD AND HERRING FISHERY V

“Repose of Fishermen,” 1856, by David Hunter Strother. Courtesy, West Virginia and Regional History Collection, WVU. From The Waterman’s Song: “No matter how enlivening, the fishery was still a Herculean test of endurance and perseverance. One observer described the ardor and stamina required of the laborers as `equal to that of a brisk military campaign in the face of the enemy.’ The fish ran so bountifully during the six- to eight-week peak season that the fishermen worked the seines every day of the week, all day and all night. …. Edmund Ruffin … visited several seine fisheries in the hectic midst of such fish runs…. He observed that `the hands, like sailors at sea, work and rest … not by day and by night, but by shorter `watches.” William Valentine likewise marveled at `what regularity and system they manage so as to allow time for all to rest,’ yet he acknowledged, too, that the fishermen sometimes `have almost to banish sleep….’ March was the most trying month. Often the coldest days of Albemarle Sound winters occurred in March. Those days left seines and lines frozen stiff and boatmen hacking their way through ice.”

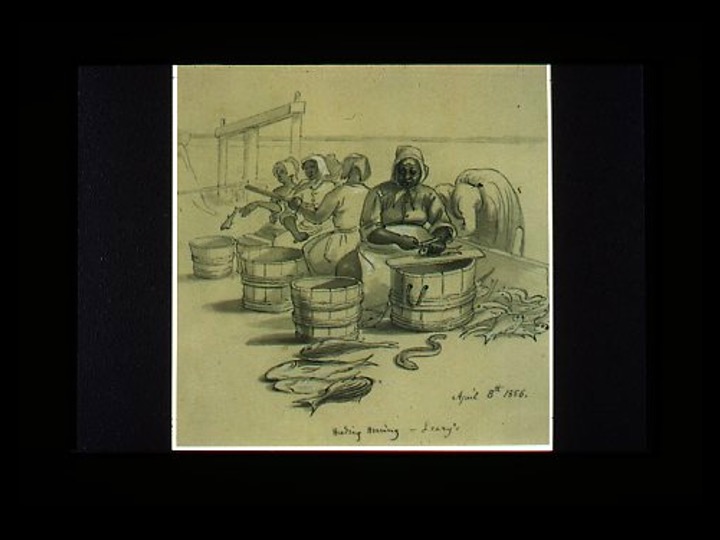

ILLUSTRATION 20: THE SHAD AND HERRING FISHERY VI

“Heading Herring,” 1856, by David Hunter Strother. Courtesy, West Virginia and Regional History Collection, WVU. From The Waterman’s Song: “Because they needed to complete their labors between hauls, the cutters, washers, and salters– mostly African American women and children– maintained a pace that rivaled that of the haul seiners. When the fishermen loaded their net for the next haul, the women and children had already begun their work on the beach…. At the Montpelier fishery [shown here], top cutters Elvy Speight, Anna Holland, and Edy Howell headed tens of thousands of herring a day.”

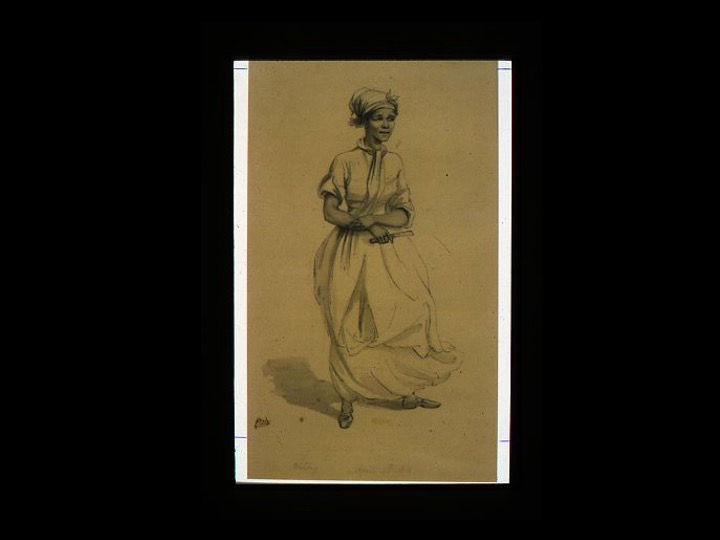

ILLUSTRATION 21: THE SHAD AND HERRING FISHERY VII

“Betsy Sweat,” fish cutter and cleaner, 1856, by David Hunter Strother. Courtesy, West Virginia and Regional History Collection, WVU. From The Waterman’s Song: “Historical documents tell us very little about how the shad and herring fishermen and women participated in the slave revolts, runaway camps, and other anti-slavery activities of the day…. What we do know is that at various times, from Gabriel’s Rebellion in 1800 to the black boatlift of slaves to freedom during the Civil War …, slaves in the Albemarle Sound vicinity conspired with one another quickly, methodically, and over large distances. Better cover for the far-flung plotters to convene is hard to imagine. One has to suspect that the shad and herring fishery played a central role in building a regional African American culture and in holding together the anti-slavery movements that percolated through the Albemarle.”

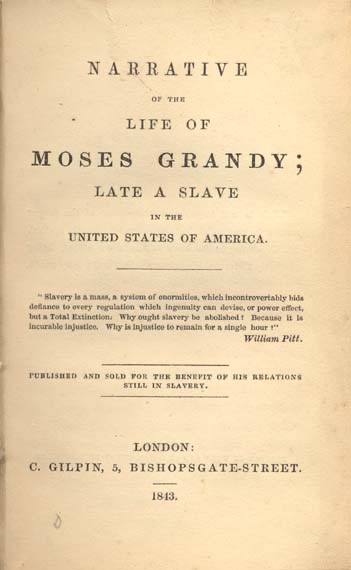

ILLUSTRATION 22: MOSES GRANDY

Moses Grandy was an enslaved waterman who grew up in Camden, a small port on the Pasquotank River in northeast N.C. Born in slavery in or about 1786, he was at different times a ferryman, a lighter captain, a deckhand on a sloop, captain of his own sailing vessel, a merchant seaman and a whaler. After gaining his freedom, he described his life in slavery in his Narrative of the Life of Moses Grandy; Late a Slave in the United States of America.

ILLUSTRATION 23: “A MAN IN EVERY SENSE OF THE WORD”

The schooner Maggie Davis near Beaufort, ca. 1890. From The Waterman’s Song: “Several decades after [Moses] Grandy had left the South, there was also a local slave waterman named George Henry who was … master of the coasting schooner Llewyllen.” In an 1894 memoir, “he discussed…both the coarser features of a black waterman’s life and the struggle for manhood that every black watermen encountered ashore. Henry remembered his younger self as a `very profane man, uttering oaths at every word … [and] as `the king of the Devils.’ He was a sailor’s sailor, he seemed to be saying, and was not a man with whom one trifled…. He also recounted how, one night while docked in Richmond, he threatened a white watchman with `blood pudding’ if he tried to report him for breaking curfew. Beyond frolics and fistfights, Henry aspired to prove his manhood through his seamanship and hard work. `I didn’t know what sleep was day or night,’ he wrote, `for … I was determined to let them see that though black I was a man in every sense of the word.”

ILLUSTRATION 24: “ABOLITIONIST AND MARITIME CAPTAIN”

Last year descendants of Moses Grandy were among those who gathered in Camden, N.C., for the unveiling of a state historical marker in his honor. Photo by David Cecelski

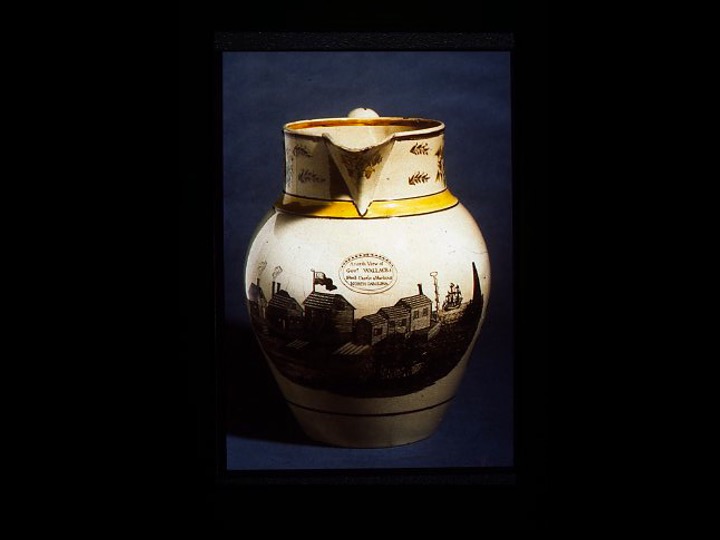

ILLUSTRATION 25: SHELL CASTLE ISLAND

From The Waterman’s Song: “Slaves figured prominently among the watermen’s families at Ocracoke Inlet. In 1810 Portsmouth had a population of 225 whites, 115 slaves and one free black. That same year, Shell Castle Island [pictured in this ceramic engraving from ca. 1790) … had a population of 18 whites and 10 slaves. [Shell Castle] was also a way station for a larger number of slave river pilots, sailors, and lighter crews who sailed ack and forth between the inlet and ports inland. . . . In the spring of 1831, approximately 30 slaves, purportedly including the entire male slave population of Portsmouth village, confiscated a schooner and fled north into the Atlantic, their flight cut off only by an unseasonably late nor’easter that disabled their vessel.” Photograph courtesy, North Carolina Museum of History

ILLUSTRATION 26: A SAILOR NAMED NED

Ned, a sailor, drawn by David Hunter Strother during a visit to North Carolina. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, March 1857. Courtesy, the Mariners’ Museum, Newport News, Va. From The Waterman’s Song: “On such waterfronts, [Moses] Grandy also met black mariners who hailed from every port on the eastern seaboard, as well as from the British, French, Spanish, Dutch, and Danish colonies in the Caribbean. Blacks composed the large majority of deckhands on the local vessels that traded with the West Indies, and a white lady in Washington [N.C.] long recalled those `large strong West Indies Negroes’ with their `bright bandanas … and large golden rings that hung from their ears.’ By working alongside such maritime laborers, slave watermen like Grandy helped local slave communities overcome their masters’ attempts to keep them isolated from one another and uninformed about antislavery movements stretching from Boston to Port-au-Prince.”

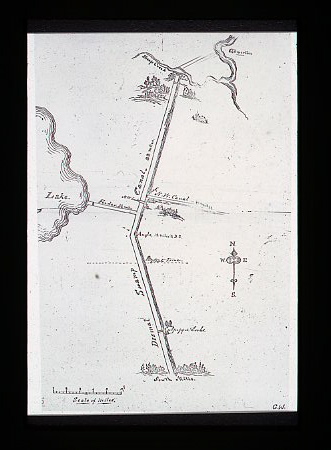

ILLUSTRATION 27: THE DISMAL SWAMP CANAL

Drawing of the Dismal Swamp Canal, ca. 1840, in the John Byrd Papers, Southern Historical Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill. Building canals and dredging channels was also a kind of maritime labor that enslaved African Americans were forced to do, but they were rarely jobs that afforded any hope of freedom. From The Waterman’s Song: “Canal digging was the cruelest, most dangerous, unhealthy, and exhausting labor in the American South…. `The Negroes are up to the middle or much deeper in mud and water, cutting away roots and baling [sic] out mud,’ remembered Moses Grandy…. Just after 1800…, an Englishman named Charles Janson took shelter at a slave labor camp owned by John Gray Blount [in Hyde County]. Janson found there approximately 60 slaves who in two years had dug a mile-long canal into a remote juniper swamp. They worked, he said, `in water, often up too the middle, and constantly knee-deep.’ They lived in log or thatch huts, probably like ones described in the Great Dismal Swamp as being `secured from inundation on high stumps.'”

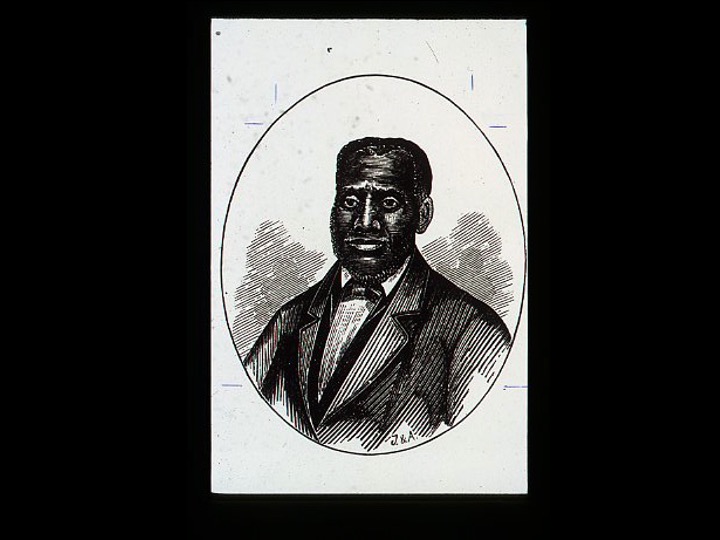

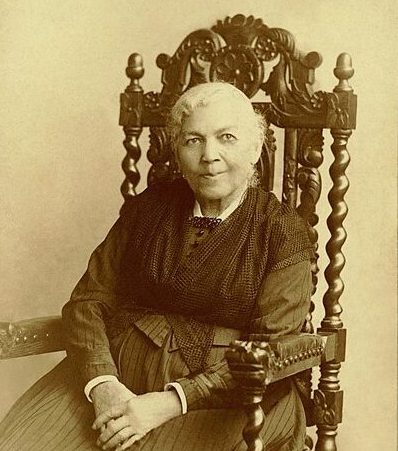

ILLUSTRATION 28: THE SLAVE PILOT PETER

The Rev. William Robinson, seen here, was the son of a slave pilot named Peter who played a central in the Underground Railroad in Wilmington Harbor in the decade before the Civil War. He worked closely with two Quaker oystermen to secret fugitive slaves onto sailing vessels bound for the northern states. “Father was with Messrs Fuller and Elliot every day towing them in and out from the oyster bay. This gave them an opportunity to lay and devise plans for getting many [slaves] into Canada….” From The Waterman’s Song: “[Their] success… was evident in October 1849, when a correspondent to the Wilmington Journal complained that `it is almost an every day occurrence for our negro slaves to take passage [aboard a vessel] and go North.” They were, however, ultimately found out. Peter was sold into the Deep South. According to Rev. Robinson’s account, at least one of the Quaker oystermen disappeared from Wilmington without a trace and was never seen again by his family. (Illustration from William H. Robinson, From Log Cabin to the Pulpit; or, Fifteen Years in Slavery, 3rd ed. (Eau Clair, Wis., 1913)).

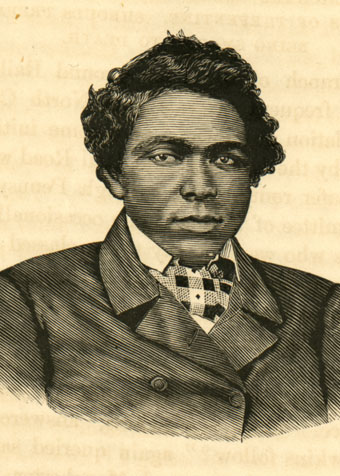

ILLUSTRATION 29: THOMAS H. JONES

From The Waterman’s Song: “Thomas H. Jones loaded and unloaded cargo on the Wilmington waterfront, where he encountered sailors and boatmen from places far and wide. Jones ultimately found a master of a vessel who was prepared to carry his wife, Mary, and their three children to New York and later negotiated his own escape with a black sailor bound for the same city.” Jones sailed to north in the hold of a brig named the Bell. (Image is from Thomas H. Jones, The Experience of Thomas H. Jones, Who Was a Slave for Forty-three Years (Boston, 1862).

ILLUSTRATION 30: ABRAHAM H. GALLOWAY

Abraham Galloway– the subject of my book The Fire of Freedom— escaped from Wilmington hidden in the hold of a schooner in 1857. He went first to Philadelphia, then to Canada. When he returned to the North Carolina a few years later, he was a Union spy and a central figure in the organizing of the 35th Regiment, United States Colored Troops. Etching from William Still, The Underground Railroad… (Philadelphia, 1872).

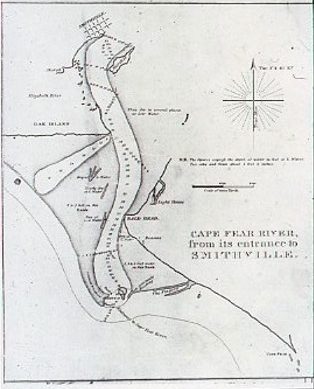

ILLUSTRATION 31: THE CAPE FEAR RIVER

“Cape Fear River, from its Entrance to Smithville, 1806. Courtesy, N.C. Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill. From The Waterman’s Song: “Political leaders viewed black sailors with the greatest wariness. `They are of course,’ wrote the Wilmington Aurora’s editor, “all of them, from the very nature of their position, abolitionists, and have the best opportunity to inculcate the slaves with their notions.’… Slave patrols were known to flog and jail back seamen for the most minor infractions of racial decorum… As a further deterrent, white authorities severely punished free black sailors caught aiding runaways…. In 1855, the Bertie county Superior Court sentenced [a black sailor named] Alfred Wooby to hang for concealing a slave on a schooner headed down the Roanoke River.'” On the Cape Fear River, authorities required vessels leaving the harbor to be fumigated twice to drive runaway slaves out of their hiding places, once in Wilmington, and a second time at Southport.

ILLUSTRATION 32: HARRIET JACOBS

Harriet Jacobs grew up in maritime Edenton and escaped from the seaport in the hold of a sailing vessel in 1842, protected by African American sailors. Years later she wrote: “God… gave me a soul that burned for freedom and a heart nerved with determination to suffer even unto death in pursuit of … liberty.” (From Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself, edited by Jean Fagan Yellin.)

ILLUSTRATION 33: A SLAVE WOMAN NAMED JUNO

From my book The Fire of Freedom: “Burnside’s first warships entering Hatteras Inlet set an extraordinary phenomenon in motion: slaves inland began to take their owners’ boats and head to the Union invasion force. As soon as New Bern felll in March 1862, the city was, as Burnside said, `overrun with fugitives from the surrounding towns and plantations.’ Hundreds, then thousands of African American men, women, and children fled from bondage in Confederate territory to freedom…. That boat lift reached deep into the state’s interior…. A crowd of slaves, `patched until their patches themselves were rags,’ sailed from the river port of Plymouth all the way to Roanoke Island…. On the Chowan River, slaves stole a dinghy and sailed away while their owner took potshots at them from shore. Another night, a slave woman named Juno gathered her children into a dugout canoe and paddled down the Neuse River to New Bern. At Columbia, on the Scuppernong River, a crowd of slaves stole a schooner and fled to freedom. A little west of there, a black boatman known as `Big Bob’ confiscated a vessel and carried 16 slaves down the Tar River to freedom, then turned and went back upriver for more.” This photograph is of a fugitive slave named William Heady who fled all the way from a plantation near Raleigh to New Bern sometime between 1863 and 1865. Photo courtesy, Library of Congress

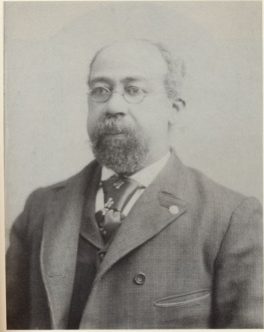

ILLUSTRATION 34: WILLIAM GOULD I

Portrait of William Gould. From The Waterman’s Song: “Another firsthand account of slavery, the diary of William Gould I, reveals how far into tidewater plantation society this black maritime culture reached. A New Hanover County planter owned Gould, a slave mason, but Gould worked at least occasionally in Wilmington…. In 1862, early in the Civil War, Gould escaped his plantation by sailing a sloop to a Union blockader…. “Photo courtesy of William Gould IV

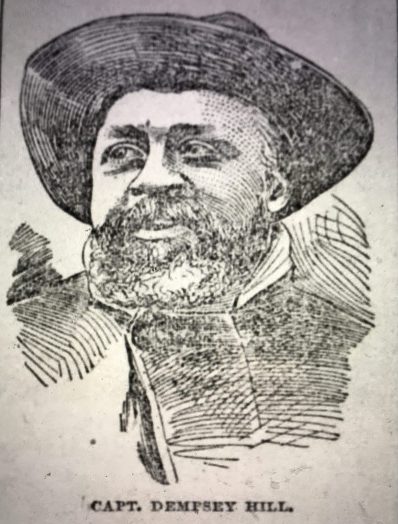

ILLUSTRATION 35: CAPT. DEMPSEY HILL

Portrait of Dempsey Hill, who was born into slavery in Beaufort, N.C. ca. 1830. From The Boston Globe, 5 June 1891. From my article “`We are Five Africans Seeking Freedom”: “Late one night in the fall of 1861, a slave waterman named Dempsey Hill slipped into the customs house in Beaufort, N.C., removed copies of the latest nautical charts and buried them in the local cemetery…. Not long after, on a pitch black night, Hill and four other slave watermen returned to the cemetery and retrieved the charts. They then made their way to the waterfront a block south, being careful to avoid Rebel patrols. They stayed low and moved quickly down a wharf, commandeered a pilot boat and set sail…. As the moon came up, they could see the masts of Union naval vessels, part of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. The five black men steered toward the closest Union ship. As they approached, the ship’s guns rolled out and a voice called out and demanded to know who they were, friend or foe. Dempsey Hill and his companions shouted over the dark waves: `We are five Africans seeking freedom.'”

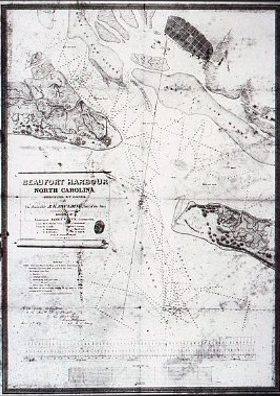

ILLUSTRATION 36: THE CAPTURE OF BEAUFORT

From The Waterman’s Song: “Slave watermen brought the Civil War to Beaufort, N.C., on the night of April 22, 1862. The old seaport’s citizens were sleeping peacefully, confidant that the guns of Fort Macon stood between them and a Union assault for at least several more days. Unbeknownst to them, local slave fishermen stood ready to launch rowboats carrying Federal troops from a secluded wharf 3 miles west. George Allen, a corporal in the 4th Rhode Island Volunteers, later recalled that the fishermen were `thoroughly conversant with these waters, and were faithful guides.’ Hidden from the fort Macon lookouts by darkness, they snaked the boats through the labyrinthine shoals of Bogue Sound and navigated a narrow channel across the mouth of the Newport River. Then, without a word spoken…, they slipped the craft beneath Fort Macon’s 10-inch cannons at pistol-shot range…. then let the incoming tide drift the Union troops into the harbor…. At sunrise…, Beaufort citizens awoke to find bluecoats pickets patrolling their sand-and-oyster-shell streets.” (James Glynn, “Beaufort Harbor,” 1839. Courtesy, N.C. Collection, UNC-Chapel Hill.

ILLUSTRATION 37: A NAVY SAILOR I

Unknown sailor in the Union Navy. Approximately 19,000 black men served in the Navy. In 1863, nearly one in four men serving in the Union navy were African American. A far larger number of African men– approximately 180,000– served in the Union army during the Civil War. Courtesy of Special Collections and College Archives, Gettysburg College

ILLUSTRATION 38: A NAVY SAILOR II

After confiscating a sloop and sailing out to one of the Union Navy’s vessels blockading the Cape Fear River, Wiliam H. Gould I (center) enlisted in the Navy and served aboard Union vessels along that part of the North Carolina coast and as far away as the French coast. His sons pictured here with him all served in the United States Armed Forces either in the Spanish American War of 1898 or in the First World War. This photograph originally appeared in the NAACP’s magazine The Crisis in March of 1917).

ILLUSTRATION 39: “THE REVOLUTIONARY IDEAS OF FREEDOM”

I thought that I might conclude with a few words from The Waterman Song’s chapter on Abraham Galloway, the African American rebel who spent his early life enslaved in Southport and Wilmington. From The Waterman’s Song: “During the reactionary era of the 1890s and early 1900s, white historians replaced thoughtful, heroic black figures such as Galloway with images of corrupted, deferential blacks…. Galloway and likeminded black insurgents were purged from the southern past, and so too was any understanding of the maritime slave culture that had produced them. They can be put into their proper historical context only by understanding their roots in the African American maritime society of the slave South and its revolutionary course through the Civil War. Galloway’s story traces in miniature the emergence of a subversive politics out of a black maritime culture that was generations old. In his mercurial life, we see the revolutionary ideas of freedom and equality espoused by the likes of David Walker and Nat Turner collide with an oppressive politics that was born and bred in the white supremacy of the Old South. The contest between the two visions would rip the South apart and tear men’s and women’s souls to shreds.”

-END-

My lecture is part of Living History Day at the Cameron Art Museum, an annual community event held on the anniversary of the Battle of Forks Road– a Civil War battle that took place on the grounds where the museum stands today and in which African American Union troops played a central role.

The day’s activities run from 10 AM to 5 PM and are free to one and all. You can find out more about the day here.

Fascinating. It awakened many memories from the 30 years I spent operating an antique print and map store in Nags Head. Needless to say the Strother drawings from Harper’s were often in my inventory whenever I could locate copies. I envy the people who were able to attend your lecture. Regards, Jack Sandberg (now living in Baltimore where Frederick Douglass is well remembered).

LikeLike