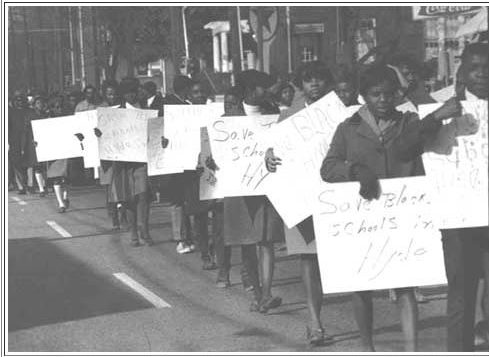

Swan Quarter, N.C., fall of 1968. Courtesy, N.C. Museum of History

This is the 1st part of a series celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Hyde County, N.C., school boycott, a remarkable chapter in the history of America’s civil rights movement and the subject of my first book, Along Freedom Road

The villages and natural areas around Lake Mattamuskeet are some of my favorite places on the North Carolina coast. They make up the mainland part of Hyde County and have a singular austere beauty: endless miles of salt marsh, great swamplands, glorious sunrises and a landscape of woods and fields dotted with lovely old churches and fish houses.

One of the things I like most about Hyde County is that, in the wintertime, you can almost always hear the haunting cries of the birds—the hronk, hronk, hronk of the Canada geese, the snow geese’s plaintive culk, culk and the tundra swans that sound like baying hounds somewhere far-off.

The great lake draws the migratory birds all the way from the tundra at the edge of the Arctic Sea and Greenland. When you live in Hyde County, as I did for a year when I was young, the soft murmur of their cries on the lake at night sounds like the Earth’s heartbeat.

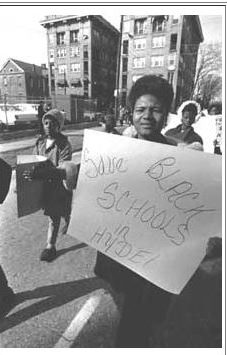

The Hyde County protestors during the first march to Raleigh, 1969. Courtesy, N.C. Museum of History

The county sits on the northern edge of Pamlico Sound and water is everywhere: the great estuary intermingling with lakes and tidal creeks, bogs and pocosins and old slave-dug canals.

Ocracoke Island is in Hyde County and attracts a busy tourist trade and new residents. But on the mainland, where most of the county’s people live, all is quiet. There the population has been declining steadily for more than a century. Whole villages have disappeared, lost to the swamps and tides.

The county has been poor for a long time, too. In the 1950s and ‘60s, it was one of America’s most impoverished counties.

Today even the county seat, Swan Quarter, has a population of less than 500 residents. In 2003 Hurricane Isabel nearly swallowed up the community. When you visit, you will see that the village looks as if it is still trying to decide whether or not it is time to throw in the towel.

The county has two other towns, Engelhard, a fishing village on Far Creek, which has a population of five or six hundred, and Fairfield, a long-fading timber village on the north side of the lake, on the edge of what the early colonists called the Great Alligator Swamp.

Today I think a state prison is the county’s largest employer, but when I lived there most people made their livings as crab pickers, oyster shuckers, fishermen, farmers and field hands.

That year I occasionally met people from other places, too—often times, recluses and runaways, hiding from something or licking wounds, or sometimes doing things they ought’en to have done (where they hoped nobody would notice), living on the far edge of the world.

You might not think Hyde County was the kind of place where one of the most extraordinary events in America’s civil rights history occurred, but it did happen there, in 1968 and 1969, and it was the subject of my first book, which was called Along Freedom Road.

Saving Historically Black Schools

Fifty years ago this week, Hyde County’s African American families pulled their children out of the public schools. They stayed out of school for an entire year. They marched day after day for months.

Ironically, a school desegregation plan sparked the black community’s boycott. In 1954, in Brown v. the Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court had ruled that racially segregated schools were unconstitutional.

As in most of the state’s other school districts, Hyde County’s white leaders resisted the Supreme Court’s ruling for 14 years.

Finally, under pressure from the federal government, most of the state’s school districts allowed black and white children to go to school together between 1968 and 1971.

But as in the rest of the South, white political leaders turned school desegregation into a one-way street.

In nearly all school districts, those white leaders closed historically African American schools, even when they were newer or had better physical plants than their white counterparts.

White school leaders sent black children to previously all-white schools, and they discharged or demoted black principals. They fired a high proportion of black teachers. In many cases, they relegated black children to a second-class status within desegregated schools.

Many black communities reluctantly accepted this kind of school desegregation, no matter how galling and unfair.

After all, they had been struggling for decades to end Jim Crow schools. On the cusp of victory, many black leaders worried that they might spark a white backlash that would jeopardize school integration if they challenged the racially discriminatory way that local, state and federal leaders were carrying out the Supreme Court’s ruling.

Hyde County’s African American families had a different way of thinking. They were very, very proud of their schools and of a black tradition of education that had sustained their children’s spirits and prepared them for the future since the first days of freedom.

They had been prepared to make sacrifices for school integration. They understood that everybody would have to give up something in order to accomplish a successful merger of the white and black schools.

But they heard what was happening in other counties in eastern North Carolina: black schools closing, black principals and teachers being demoted or fired, black children being punished disproportionately and shunted into special education classes, climates of racial hostility, black voices no longer heard on school issues.

When Hyde County’s black families learned that the local school desegregation plan required closing their historically black schools and sending their children to the county’s one white school, they decided it was time to take a stand.

If this is what “school desegregation” meant, they would keep their own schools. They said no.

“We were all brothers and sisters then”

For an entire year, thousands of Hyde County’s African American citizens marched and protested and petitioned. They started alternative schools in their churches.

They marched all the way to Raleigh—twice. They endured tear gassing, and they fought a gun battle with the Ku Klux Klan.

Arrested for nonviolent civil disobedience, they filled the jail in Swan Quarter. When they ran out of room in the local jail, authorities sent them to jails in a half-dozen other towns in eastern N.C. They sent some of the young ladies all the way to the Women’s Prison in Raleigh.

And the authorities didn’t know what to do with all the little children, the elementary school students and the 11, 12 and 13 years olds—and they didn’t know what to do with the grandmothers, either.

Hyde County’s black citizens and supporters marching toward the N.C. General Assembly in Raleigh, N.C. Courtesy, N.C. Museum of History

Hyde County’s black children went into those jails singing freedom songs, filled with joy, and determined.

“If we do not do something now, it will never happen,” they told Dudley Flood, a representative from the N.C. Dept. of Public Instruction that eventually helped to negotiate a settlement to the school boycott—one that, for the young people, was an extraordinary victory.

They may have been the children of crab pickers, tenant farmers and oystermen, but Flood was awed by their commitment and dedication, and by their intellectual curiosity. He marveled at how quickly they learned and grew. He told me that he wished he had a room full of students like them when he had been a public school teacher.

He admired their commitment to the African American freedom struggle, too. The children, he said, “had become convinced that they owed it to future generations.”

“You walked, talked, ate, thought, … lived for the movement,” one of those students, Alice Mackey Spencer, told me. “It’s all you did.”

Another of the former teenage civil rights activists, Thomas Whitaker, told me that he “felt like I was giving myself completely to something larger and more important than myself.”

“We were all brothers and sisters then,” he and others told me again and again when I was writing Along Freedom Road.

Celebrating A Half Century Later

In a few days, those young people are coming home again. Over Labor Day weekend, they’ll be gathering at one of the county’s historically African American schools to honor the 50thanniversary of the school boycott.

They’ll be celebrating those times “when they were all brothers and sisters.” They’ll be remembering those days when the whole nation was watching them.

They’ll also be honoring all those who contributed to the school boycott, but who aren’t with us anymore.

I hope they will take a collective bow. They accomplished so much and inspired so many. And for those who would listen, they offered lessons about what really makes a good school and what really matters most in a child’s upbringing that are as relevant today as 50 years ago.

My wife Laura and I will be there, too. I’m honored to be a small part of the celebration and I’ll try to share as much of what happens there on this blog as possible. And between now and then, I’ll be re-visiting a few of my favorite stories from Along Freedom Road here.

* * *

Next time– `In our blood from way back’– the history of the O. A. Peay School

Mr. Cecelski

Thank you so much for sharing your article. Mr. Whitaker often talks of the era during the integration of schools in Hyde. As you know, he is on the Board of Education. Our Child Nutrition Manager, Mrs. Mamie Brimmage was also quite active in the movement to integrate the schools. Both indivuals have shared very vivid accountings of events during this time.

Additionally, I have had one individual who was involved in the shoot-out between the Klan and members of the “Movement” share with me the events of that night.

The historical significance of this upcoming event cannot be over stated. I look forward to the next article. Thank you.

Randolph Latimore, Sr.

Superintendent – Hyde County Schools

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Supt. Lattimore, Thank you so much for your note. I appreciate your thoughtful words very much, and I look forward to meeting you this weekend. Please give Mr. Whitaker my bests in the meantime– he and his generation in Hyde County are true heroes to me, as well as good friends. Most sincerely, and thank you again for adding your voice here, David

LikeLike

Pingback: Le gruyère de Hyde continue de se apercevoir par son perspective terrifié intégral – shangri-lafrontier