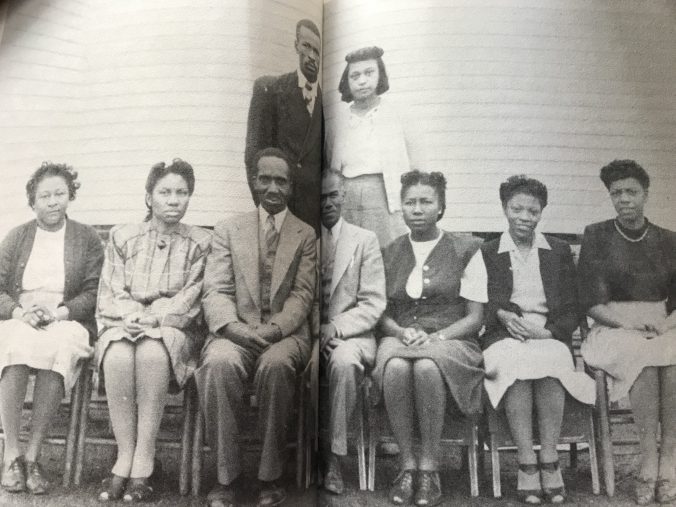

Hyde County Training School faculty, probably 1950s. Left to right, Senia Sheperd Johnson, Annie Bonner, John Raleigh Spencer, O. A. Peay, Rosa Mackey Bell, Beulah Kelsey McNair, Lucie B. Hargraves. Standing: Seward Selby, Rosaliner Hill. From Selby et.all, Hyde County History

This is the 2nd part of a series celebrating the 50thanniversary of the Hyde County, N.C., school boycott, a remarkable chapter in the history of America’s civil rights movement and the subject of my first book, Along Freedom Road

I was very young when I wrote Along Freedom Road, and the people of Hyde County taught me many important things about the history of the African American freedom struggle in eastern North Carolina.

Here on the 50thanniversary of the Hyde County school boycott, I’ve been thinking about some of those lessons.

One had to do with the history of African American schools and the pride with which black Carolinians viewed their schools during the Jim Crow era.

In 1968 Hyde County’s black parents launched the school boycott because a federally-approved school desegregation plan unjustly called for closing the county’s two historically black schools, the O. A. Peay School in Swan Quarter and the Davis School in Engelhard.

In Along Freedom Road, I described the history of the O. A. Peay School. I hope this excerpt from the book will give you some sense of why Hyde County’s black citizens would be willing to fight so hard and sacrifice so much to save their schools.

This is a slightly edited, somewhat abbreviated excerpt from my book.

* * *

Freedom Schools

For black Hyde Countians in 1968, the O. A. Peay School embodied a rich educational heritage that dated back at least a century. One has to begin looking that long ago to understand how they reacted to the threat of losing the school.

When the school board decided to close the O. A. Peay School and the Davis School, the older black residents could still recall their parents’ and grandparents’ stories about attending classes in bush tents only a few months and years after gaining their freedom in the Civil War.

As a black educator said later, the commitment to education was in “our blood from way back.”

By 1872 black residents had already built several one-room schoolhouses. They supported 16 schools by 1886, 20 by 1896.

They cleared the land and erected the buildings with their own hands and somehow found money enough to supplement a teacher’s salary and purchase a slate for most children. Furnished only with long benches and cast iron stoves, the schools often served 50 students in a 16 x 24 foot room….

Those grade schools grew into a fundamental part of black life in Hyde County. Black citizens organized schools not only in the larger settlements of Fairfield, Engelhard, Swan Quarter and Scranton, but also in remote hamlets like St. Lydia, Slocumb, Nebraska, the Cove, California and the Ridge.

The Tiny Oak School, for example, founded in 1887 and located “O’er the Quarter,” drew black children from a 4-mile radius from Tiny Oak to Juniper Bay.

Such schools figured prominently in the daily life of their surrounding communities. Local residents used the school buildings for square dances, basket parties, festivals and other assemblies. Schools and churches often shared a building, and church congregations saw support and upkeep of the school as an extension of their Christian duty….

By the end of the 1930s, black citizens supported as many as 40 such grade schools in Hyde County….

Mary Cox and the Sladesville Graded School

One of these community schools, located in Sladesville, evolved into the O. A. Peay School. Mary W. Cox and her older students cleared the land for the Sladesville Graded School in 1913.

Three years later, the county’s first “Negro supervisor,” Rhoda Warren, began to campaign for a campus in Sladesville that would offer Hyde County’s black children more than a grade school education.

The Alabama native clearly possessed extraordinary will, vision and faith…. Black schools still possessed extraordinary disadvantages compared with white schools. As late as 1916, neither the state of North Carolina nor any of its counties had financed a single four-year public high school for black children.

Even in the grade schools, black teachers then earned only half what their white counterparts did . . . and public investment per pupil in school property was four to one in favor of white children.

The secondary education campaign sweeping the white South had totally excluded black schools. Consequently, Hyde County blacks were forced to accept the same kind of “double taxation” that other black southerners had experienced since Reconstruction.

They paid local taxes that white public officials diverted to support the white schools, and then made private contributions of cash, land and labor to bolster their own schools.

The Hyde County Training School

Rhoda Warren died in 1919, but she had sown seeds that bore fruit in ensuing years. While students temporarily attended classes at Zion Temple Baptist, an important Sladesville church founded only 2 years after the Civil War, black citizens remodeled and expanded the grade school in 1921.

Administration Building, Hyde County Training School, Sladesville, N.C. From “Memories of the Hyde County Training School Banner, 1940”

They renamed it the Hyde County Training School (HCTS) and offered 9 grades the first year and 11 grades by 1928.

The school would always struggle against official indifference and a scarcity of funds. Compared with the white high schools in Swan Quarter and Engelhard, the HCTS would always be allocated less money for equipment, books, bus service, staff, salaries and upkeep….

Oscar A. Peay arrived at the Hyde County Training School in 1930 during the Great Depression. Originally from the Deep South, and a graduate of Atlanta University, the devout young teacher committed his life to the school, serving as principal until his retirement in 1961.

Peay and his wife, Mary Carter Peay, the school’s mathematics teacher, recruited a group of talented and earnest educators who understood the poverty and racism that hindered blacks in Hyde County.

Those men and women believed that education was the only route available by which their students and the community could “advance as a race….”

The HCTS teachers believed that they had to sustain “a sense of mission” not shared by white educators. They were preparing their students “to contribute to society [and] to help somebody.”

They believed that the black community would depend on their students, and HCTS alumni long remembered the sense of obligation to make a contribution to the community that was instilled in them.

Peay and his teachers believed that local social conditions required special sensibilities in and out of the classroom. They acquainted themselves with their students at home, in the community and at church, and they tried to employ all of those institutions to improve the children’s educations.

O. A. Peay’s Legacy

The quiet rural atmosphere in Sladesville favored this approach. Located on a marshy peninsula between Rose Bay and the Pungo River, the village was small and isolated, and its life revolved around the new school.

The HCTS teachers and local boosters acted as surrogate parents for the students, and they welcomed the young people into a tight-knit and caring community.

Their concerns ranged from assuring that the students ate good meals to chaperoning dates.

Even after the school moved to Job’s Corner [on the edge of Swan Quarter] and the students no longer boarded nearby, the HCTS educators still understood that parents who worked day and night at a seafood packing house, or who had moved north to find a job and left their children to be reared by grandparents, had entrusted them as much to oversee the students’ general well-being and development as to teach the three R’s.

This is an edited excerpt from David Cecelski, Along Freedom Road and is used courtesy of the University of North Carolina Press

Community and school life naturally intertwined, especially during the Sladesville years.

Phillip Greene, a Peay protégée who became the school’s principal in 1971, remembered that the founder required his students to attend Sunday school classes and regularly taught Sunday school lessons that complemented course work at the training school.

Teachers attended church with the students and often visited the families where they boarded.

Conscious of their roles as mentors, they allowed older children to accompany them to community events and even on daily errands that provided opportunities for conversation and guidance.

The school also became a community center for blacks all over Hyde County. Civic and church groups held adult classes, choir rehearsals, benefit concerts and social events in the main building, and the HCTS staff organized clubs and other activities that included both students and unenrolled children.

“You can do something”

The HCTS teachers set high standards and constantly put new challenges in front of their students. According to the alumni, the teachers urged them to improve themselves and prodded them not to be satisfied with the limitations that Hyde County imposed.

“You can do something,” Peay and his teachers repeatedly told the students. “You can make it.”

Though few of their students’ parents had graduated from grade school, the educators encouraged the children to finish twelfth grade . . . and to continue their educations . . ..

The teachers also emphasized a duty to Hyde County, and they fully expected the better students to return home to teach in the schools.

A stern dress code, strict discipline and daily prayer reinforced these high expectations. . ..

The paucity of county or state support required the Hyde County Training School to depend on the black community. Guided by the educators, especially vocational teachers B. W. Barnes and Seward Selby, the older students and many community volunteers improved the school facilities. . . .

Over the years, they landscaped the school grounds, drained and built up the playground, laid cement walkways, replaced walls, added a lunchroom, purchased buses and spearheaded many other improvements.

Community people regularly supplied the school with firewood, supplies and equipment and often boarded both teachers and students.

Moving to Job’s Corner

When the school relocated in Job’s Corner in 1953, black citizens donated a major portion of the land. Parents and alumni later raised funds for the playground, athletic and laboratory equipment, books, cafeteria furniture, a new kitchen stove and gymnasium curtains. . . .

Founded in the early 1950s, the alumni association perhaps best reflected this school loyalty and commitment. The HCTS alumni first organized chapters locally and in Brooklyn, New York, where black Hyde Countians had been migrating in large numbers for generations. . . .

Prof. O. A. Peay crows the queen at the annual May Day Festival at the Hyde County Training School. From Selby et. al., Hyde County History

The alumni chapters held local fundraisers and reunions to support the school and the children “back home.” Their members identified job and educational opportunities for HCTS students, and they often oriented recent graduates to new homes in Washington, Philadelphia and Brooklyn.

For men and women who had moved away from Hyde County reluctantly, the alumni association not only connected them to the training school but also soothed their homesickness for family and community down south. It was a powerful bond to their childhoods as well as to their native land.

This bond bred a fierce loyalty. By 1960, the Alumni homecoming had become the biggest social and cultural event in Hyde County. Every Memorial Day weekend, busloads of former classmates and educators returned home from across the nation to celebrate their achievements, the promise of the new students and the tradition of struggle personified by the school.

At the request of black citizens, the school board renamed the Hyde County Training School in honor of O. A. Peay in 1963.

Under his leadership, the school had survived and become a nucleus of the black community despite terrible underfunding, racial discrimination and official neglect.

By 1968, the O. A. Peay School was a source of inestimable pride to Hyde County blacks and symbolized their aspirations for education and racial advancement.

Though the institution was obviously under the formal authority of the Hyde County Board of Education, black citizens believed that, in the most meaningful sense, the O. A. Peay School belonged to them.

* * *

Next up in my countdown to the Hyde County school boycott’s 50thanniversary— “Letha Selby Stands Up”